1. Cassatt's early years

Cassatt was born in Allegheny City in Pennsylvania, U.S. She spent her early years in America, as well as spending five years in Europe.

The Cassatts saw travel as a key component in a complete education and they insisted on taking their children to visit the most prominent capital cities in Europe. They stayed in France and Germany from 1851 to 1855 and it was here that Cassatt learned German and French.

Cassatt's father

Her father, Robert Simpson Cassatt, was a wealthy stockbroker whilst her mother, Katherine Kelso Johnston, was part of a successful banking family.

From an early age, Cassatt had ambitions to become a professional artist but her father greatly feared the impact that a career in art would have on his daughter. He mistrusted the morals of the male art community and was concerned about the backlash from society his family would receive if his daughter were to become an artist.

At the same time, he believed that pursuing art on an amateur level was a worthwhile pastime for a young lady. Being talented at painting was considered a virtue for a society woman.

This gave Cassatt some leeway to study as she wished but she signed her early works with her initials or middle name - Stevenson - to avoid scandal.

Cassatt's training

Her earliest art training was from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts which she attended from 1861-65. However, Cassatt quickly became bored of this form of education and in 1866 she left the U.S. to seek out a European education. Her interest in European art is thought to have originated in her earliest years when living abroad with her family.

In the 19th century, women were forbidden to study in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. As a result, Cassatt was forced to study privately. Undeterred, she worked with Jean-Léon Gérôme and other prominent French artists including Charles Chaplin and Thomas Couture.

Early successes

Her painting ‘A Mandoline Player’ was accepted to the Paris Salon in 1868. She also exhibited and successfully sold ‘Two Women Throwing Flowers During Carnival’ at the Paris Salon of 1872. In total, Cassatt had her works selected for the Salon four times. In spite of this, she was criticised for being outspoken against the Salon’s heavy-handed politics and strict conventions, which she felt, were greatly restricting.

By 1874, Cassatt had chosen Paris as her permanent residence, firmly aligning her future with the impressionist movement and making clear her aims to become a prominent artist in her own right.

Unfortunately, the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War saw her return to the U.S. fairly quickly. She was not alone as fellow impressionists Claude Monet and Alfred Sisley fled to London.

2. Cassatt’s Impressionism

Cassatt broke from the Salon in the late 1870s when she began exhibiting at the impressionist exhibitions.

She first premiered at the fourth impressionist exhibition held in 1879, also showing her work in the 1880 (fifth) and 1881 (sixth) exhibitions to follow.

This acceptance into the movement had the effect of freeing her from stylistic constraints and she described how:

“I accepted with joy. I began to live. At last I could work in absolute independence”.

Cassatt and Degas

One of Cassatt’s earliest champions was Edgar Degas. He admired her drawing and her artistic eye, which he saw as similar to his own.

Degas was the first to invite Cassatt to exhibit her work at the impressionist exhibition of 1879 and the two artists became friends thanks to their shared aesthetic, focussed on striking compositional structure and asymmetry.

Despite their closeness, it is necessary to question how equal the relationship was, especially in light of comments from Degas like:

“I will not admit that a woman will draw so well.”

Cassatt was likely a very tolerant individual: Degas was a surly and truculent individual, who revealed himself as an anti-Semite in later life.

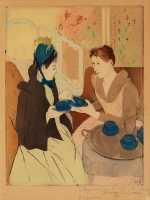

Paintings of women

Whilst undoubtedly avant-garde, Cassatt’s works deviated from the other impressionists in their imagery. She depicted modern women going about their daily lives, usually backed by blocks of colour or prints. The women in her artworks stand alone, as mothers and as individuals.

Referring to her mural titled ‘Modern Woman’ from 1893, one American friend asked Cassatt

“in a rather huffy [affronted] tone the other day, ‘Then this is a woman apart from her relationships to man?’ I told him it was.”

She was unafraid of creating images of women pursuing their own interests and spending time solely in the company of other women.

It is thought that this focus on women and frequently mothers led to much of Cassatt’s work being passed over in later exhibitions of impressionist art in France. Her work was ignored due to its all-female subject matter and not recognised for her stylistic innovations.

The impressionism Cassatt embraced was partly influenced by the limitations imposed on her by French society. Like her friend and contemporary, Berthe Morisot, Cassatt was not allowed to paint or even be in public spaces without a male chaperone. The consequence of such restrictions was that many of her paintings necessarily focussed on the domestic sphere. Nevertheless, she continued to experiment with painting ‘en plein air’ (outdoors), characteristic of the impressionists, as much as she could.

The colour black

Cassatt’s paintings often utilised a light colour palette and quick brushwork that was common to the impressionist movement. On the other hand, she did not shy away from black hues in many of her compositions, which set her apart from all of the other impressionists with the exceptions of Degas and Edouard Manet.

This is most evident in works like ‘A Woman in Black at the Opera’ from 1880 where the solid black of the woman’s fashionable dress and bonnet dominates the painting and is set against the red background. She enjoyed the drama that black could create.

3. Cassatt’s drawings

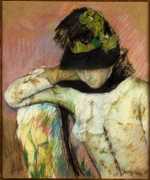

Some of Cassatt’s finest works are her pastel drawings.

Taking inspiration from Degas, who encouraged Cassatt to do away with unnecessary details and helped to shape her work into ever more striking portraits, Cassatt experimented heavily with pastels.

Introduction to pastels

When she was first introduced to the medium in the 1870s, its revival was just beginning to gather momentum. Cassatt pushed pastel drawing forward, creating ever more inventive works that centred on spontaneity and contrasting colours.

Indeed, many of Cassatt’s pastel drawings bring an entirely new approach to the medium. In works like ‘Mother and Child’ from 1914, Cassatt juxtaposed complementary colours in order to make her drawing richer and more intense. The greens of the background clash with the pink of the mother and baby’s flesh, touched with blue in the areas of shadow.

The weight Cassatt placed on drawing, etching and pastels in turn fed into her painting style. She preferred to use bold, solid lines in her paintings rather than the broken, feathery technique common to Impressionist paintings at this time. There is also a clear evolution in Cassatt’s works, moving towards increasingly fearless styles as she pushed the boundaries of her pastels further.

Japanese influence

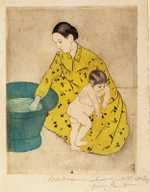

Cassatt and Degas’s drawings were both influenced by Japanese art. Parallels can be drawn between both artists’ vignettes of women washing, often nude or half-naked, and the bathing women common to Japanese prints. They diverge in the sensuality of their works, however. Degas built on the voyeuristic nature of Japanese art as evident in his ‘La Toilette’ series.

In contrast, Cassatt’s works have a more linear quality that reduces the explicitly sexualised aspects of the works. Her abstract portrayals of unclothed women, as in ‘Woman Bathing’ from 1890-91, turn the nude bodies into studies of shapes and colour rather than seduction.

Nudes

Nude artworks were highly unconventional for female artists at this time. For instance, women were not permitted to draw from nude models at the Académie Julian (a highly reputable art college). Cassatt subtly subverted the social norms imposed on her by depicting her nude women in a domestic, bourgeois setting.

In this way, she was able to study the female form in a semi-respectable way, using the stylised technique of Japanese art to further remove herself from the European tradition. Whilst her male contemporaries studied women in brothels and bath houses, Cassatt brought the illusion of decorum to her nudes, allowing her to paint as she wanted.

4. Cassatt’s Japanese prints

As well as being a painter, Cassatt was an accomplished printmaker having learnt the skill fromDegas.

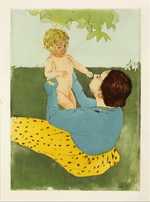

In 1890, she visited an exhibition of Japanese woodcut prints in Paris and the works she saw inspired her to make her own. Using the figures of the French women who were her regular subjects, Cassatt embarked on a new style of etching.

The Japanese theme of ‘ukiyo-e’, meaning the floating world, regularly depicted scenes of everyday life. Drawing on the work of the Japanese masters, including Utamaro and Toyokuni in particular, Cassatt aligned herself with this novel artistic movement in the 1890s.

Women in their Homes

At the same time, she experimented with bringing her own distinct edge to her works, capturing women in their homes. The women in her prints possess the same independence as in her earlier paintings. In doing so, Cassatt was able to create a unique version of the popular Japanese prints. Her works from this period diverged from Impressionism completely.

Cassatt’s enthusiastic embrace of Japanese artwork can be seen as part of a wider movement in Western art in the late 1800s, thanks to a flood of Japanese imports into the U.S. and Europe. A treaty signed in 1854 between the U.S. and Japan marked the end of Japanese isolation from the rest of the world. Consequently, Japanese culture became extremely fashionable and pervasive throughout Europe, so much so that the term ‘Japonisme’ became used to describe its influence on Western art from the 1870s onwards.

European Scenes

However, unlike other artists famous for their Japonisme, Cassatt did not use Japanese subject matter in her works. Her scenes and models were firmly European, drawing on the European tradition of the ‘Madonna and Child’, an image that had been popular since the Renaissance period. Similarly, the clothing and arrangement of the women’s hair clearly reflected their European context.

One example of this interweaving of cultural influences can be seen in ‘The Letter’ from 1890-91. The bold patterns and colours in the print borrow from Japanese prints. The personal, private act of writing a letter creates a personal story within the artwork that one can even link to Cassatt’s life as an expatriate in Paris.

Doll-like Drypoint

During this period, Cassatt also developed her own technique of etching using drypoint that she called ‘à la poupée’ or doll-like. She would trace her original sketch onto copper, as one would for making an etching, and then apply all the colours at once, using rags tied over small sticks. With the help of her printer, she would then run the plates through the press by hand. This allowed her to create the flat colour and linear style that made her prints so effective and so typical of Japonisme.

Cassatt’s work shifts from a focus on form to pattern during this time. This is not only evident in her prints but also in paintings such as ‘The Child’s Bath’ from 1893. The work combines different patterns, from the fabric of the mother’s clothing to the woven rug to the print on the wall, creating a patchwork of impressions. It also has the same flattened style that is characteristic of her etchings.

5. Cassatt’s later works & legacy

Due to her failing eyesight, Cassatt’s later works were somewhat limited.

Having purchased a chateau in Le Mesnil-Théribus in 1894, bought with the proceeds from her art sales, Cassatt began spending more time in the countryside, splitting her time between her rural home and the Paris.

Despite this move, many of Cassatt’s later works are her most daring. They exemplify the spontaneous expression that she built on through her career. In her pastels, she used broken, unblended lines to build up her compositions, at times using zig-zag and hatching to create the tones in her paintings and experimenting heavily with contrasting colours.

Failing eyesight and Politics

By 1914, Cassatt was forced to stop working as a result of her eye problems. Instead, she became involved in political movements to fight for women’s right to vote.

She was also able to see the rise of a group of Canadian artists who were inspired by her work. The all-female group based in Montreal became known as the Beaver Hall Group and was the first Canadian art association that championed professional women artists. Similarly, Cassatt inspired Lucy Bacon to study with the Impressionists in Paris.

Legacy

In her work, Cassatt confronted the traditions of the male gaze in art: her subjects are not pretty women put on display but independent actors in their own right. This daring development sets her apart from others in the Impressionist movement and is reason enough to take note of her art. However, she also innovated in both her choice of medium and style.

By constantly revising and challenging her style, experimenting with pastels, Japanese prints and bold oil paintings, Cassatt enjoyed commercial successes that were out of reach to many other women artists at this time. Furthermore, as an American impressionist Cassatt had an enormous influence on developing the tastes of the American art market.

She frequently sent paintings back the the U.S and encouraged her network of wealthy acquaintances to purchase Impressionist paintings. She advised them on which works to acquire and in doing so, was central to informing the collections of many prominent families. The H.O. Havemeyer Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City was almost entirely grown by Cassatt.

Like her fellow female contemporaries, Cassatt’s works were largely passed over after her death thanks to the art establishment’s tendency to ignore the role of women in art. However, she enjoyed more recognition from the later 20th century onwards and is now considered to be one of the most important American expatriate artists from this era.

Cassatt resources

To take your knowledge to the next level, check out our resources page - you'll find recommendations for the best impressionist books, videos and gifts.