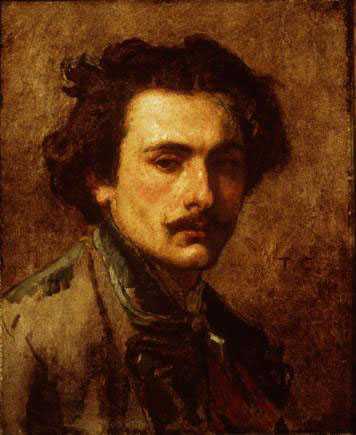

1. Early Years

Couture was born in Senlis in Northern France in 1815.

He moved to Paris in 1826 with his father, a shoemaker, and their family. In Paris, he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts after attending the École des Arts et Métiers for a year

His teachers included the academic painter Antoine-Jean Gros and the popular artist Paul Delaroche. Gros was best known for his historical work, particularly his paintings documenting Napoleon’s military career.

Along with portraits, Delaroche painted large tableaux depicting historical and religious scenes in great detail. The influence of Couture’s teachers is easy to see in his early work, both in the subject matter, the size of his paintings and the attention to detail.

Couture entered the competition for the Prix de Rome six times whilst studying at the École before he won second prize in 1837. Winning first place in the competition would have granted him the chance to study at the Académie de France in Rome, an exciting prospect for a classical painter such as Couture.

He competed twice more but was unsuccessful and subsequently opened his own atelier and exhibited his work at the Salon in Paris. It was here that he was later to achieve great success.

2. Couture’s work

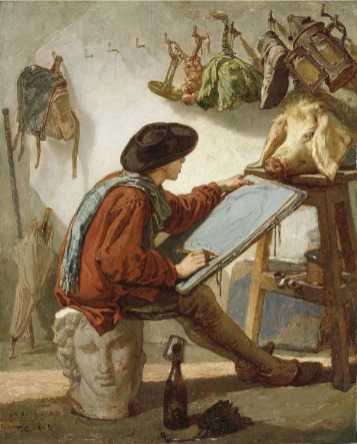

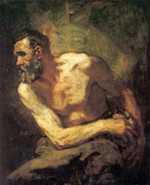

Couture’s style of painting was primarily classical, which was typical of French nineteenth century art.

However, in much of his work he used soft, dark colours reminiscent of the styles of the eighteenth century. A particularly unique technique Couture used was to keep parts of the ébauche in a final painting. This meant including the rough preliminary sketch in the finished work rather than using it purely to map out the final piece.

Couture was also well-known for his method of ‘quick painting’ which he taught his students long before the Impressionist era. This technique was used by artists particularly when painting outside.

His painting style is further characterised by his use of tonal contrasts, working mainly in dark colours except for a few bright details. For example, his portraits were often painted on a blank background showing just the head and shoulders of a subject from the side and his signature was to paint a white collar, which stood out in sharp contrast to the rest of the painting.

Couture’s best known and most critically successful work was ‘Romains de la Decadence’ painted in 1847, for which he was awarded a gold medal at the Salon that year. Inspired by the Roman poet and author of the Satires, Juvenal, Couture built this piece on the assertion that:

“We are suffering today from the fatal results of a long peace; more damaging than arms, luxury has rushed in upon us and avenged the enslaved universe.”

The Satirist also wrote “Crueller than war, vice fell upon Rome and avenged the conquered world”. These writings formed the foundation for Couture’s most famous work.

Couture painted this vast piece over three years. The painting depicts a scene of Roman debauchery set against a backdrop of traditional statues and pillars. This piece can be seen to represent the society of the past compared with the decadence of modern times. There is symbolism throughout the painting relating to Bacchus, the ancient god of wine, to confirm the sense of revelry and festivity.

In the corner of the scene stand two philosophers - in contrast to the other people in the painting they are disapproving and stern, adding to the allegory of displeasure with modern ‘civilised’ society. This disapproval is also mirrored in the statues around the group who look down on the revelry with expressions of judgement and embarrassment.

Whilst the scene in ‘Romains de la Decadence’ is clearly set in the Roman era, Couture was also providing commentary on his own society, the decline of French culture and the decadence of the ruling class during his time. This, along with the obvious skill displayed in the painting itself, contributed to the success of the piece.

After the accomplishment of Couture’s masterpiece ‘Romains de la Decadence’ at the Salon, he gained popularity and was named as one of the greatest artists of the time.

The French Republic Government commissioned Couture to create a historical painting for the Hall of Sessions of the National Assembly, to capture the formation of the Second Republic following the French Revolution in 1879. He decided to paint ‘The Enrollment of the Volunteers of 1792’ depicting Frenchmen of different social classes uniting to defend the country, which was at war with Austria.

Couture made a great number of sketches and figure studies in preparation for the painting, many of which are now held at The Musée d’Orsay. Couture’s final sketch for the painting, The Enrollment, produced in 1848, shows a triumphant procession of volunteers with workers hauling a cannon on the ground while a young aristocrat celebrates with his arms raised.

Soldiers and figures at a table are shown under billowing flags on a platform above the ground. Set against a dark sky the white and colours of some of the men’s shirts and clothes in the scene, along with the pale skin of the woman in the centre, stand out in his usual style.

Rather than purely classical figures as seen in ‘Romains de la Decadence’, Couture depicts a much more varied group of subjects such as soldiers, workers and allegorical figures including ‘Liberty’ in the centre of the piece, standing next to two girls ‘The Promises’, all symbolising optimism and hope for the future.

It is considered likely that the two girls are based on his own daughters as the figure study is entitled ‘Two Sisters (Study for The Promises in the Enrollment of the Volunteers of 1792)’. The first girl is recognisable as Couture’s daughter Berthe as she was also the subject of his 1848 painting ‘Autumn’. It follows from the title that the other girl would be her sister and his younger daughter.

Unfortunately, the French political landscape quickly changed following the commission of the work. Napoleon was elected president in 1848 and following the coup d’état, the Second Republic became the Second Empire after he named himself Emperor.

The revolutionaries' ambitions were crushed and Couture’s painting became irrelevant. Much of the final piece was left out including, most cynically, the figures of ‘Liberty’ and ‘The Promises’.

3. Couture and the Impressionists

Couture had a profound influence on Impressionist artist Édouard Manet, who was one of his students.

Manet copied Couture’s works at the Louvre as part of his studies. When Manet first arrived to learn from Couture he is reported to have said “I don’t know why I’m here. When I arrive at the workshop, I feel like I’m entering into a grave”.

Despite the dissimilarities between them, Manet learnt valuable techniques and skills from Couture during the six years that he studied under him. He was especially influenced by Couture’s use of tonal contrasts.

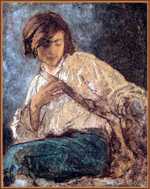

One of Couture’s portraits ‘Soap Bubbles’, painted in 1859, shows a young boy sitting at his desk watching bubbles float in the air in front of him. In the traditional style, there is symbolism and hidden meaning to be found in the details Couture provides in the background of the image.

For example, the books on the desk show that the boy is studying at school. There is a laurel wreath behind the child and the paper on the mirror reads ‘immortalité’, the French word for ‘immortality’ whilst the bubbles themselves are naturally symbolic of the transient nature of life.

The painting is highly detailed, even the fabric of the chair that the boy is sitting on has an intricate pattern. Characteristic of Couture’s style, the piece uses dark colours. Interestingly, even the bubbles are not in light but rather painted into the darkness.

The only light in the room illuminates a section of the mirror and paper. Also, in the typical style of the artist, the white collar of the subject stands out in contrast to the rest of the painting, drawing focus to the boy’s face and his contemplative expression.

In 1867, his former student, Manet, was inspired to paint a similar subject in his own style. Manet’s painting ‘Boy Blowing Bubbles’ shows a young boy against a dark background holding a bowl and using a straw to form bubbles.

Like Couture’s painting, the bubbles represent the transience of life and similar to Couture’s style, it is very dark in tone. However, unlike Couture’s ‘Soap Bubbles’, there is no background detail at all.

Other than the subject, Manet has only painted a waist height wall in front of the boy. This serves to focus all the viewer’s attention on the boy and the bubbles he is blowing.

We can also see Couture’s influence in the sharp tonal contrast between the dark of the background and the bright white of the boy’s clothing. In contrast to Couture’s earlier work, there is no overt symbolism in the piece and the expression of the child in Manet’s painting is more of concentration rather than consideration.

Along with painting en plein air, one of the defining techniques used by Impressionist artists was the act of ‘painting quickly’. This was not only a vital tool when capturing a moment in time but also contributed to the overall goal of producing an impression of something rather than depicting it in meticulous detail.

Notably, Couture was both using and teaching the method of ‘painting quickly’ long before the Impressionist movement took shape, inspiring many of his students to experiment with the technique.

When Couture later published his teaching methods and techniques, he included quickly drawn figure studies ‘étude de figures’ as a step-by-step guide for his students to follow.

Whilst Couture himself was certainly not an Impressionist, like the other artists of the movement he did not agree with the traditional academic establishment, namely the exclusivity of the teaching methods. He published his techniques and processes for anyone to read as a direct challenge to the art schools of the time.

His style of painting was very traditional, in contrast to the work of the Impressionist artists, but his rejection of the idea that artistic education should be exclusive and limited to the academies was similar to the thoughts behind the movement.

Perhaps it can be said that the shift in mindset was equally as important as the change in painting style from Academism to Impressionism and Couture, despite being an academic painter himself, was certainly an advocate for a different way of thinking specifically with regards to teaching methods at the time.

4. Later career

Couture’s work was exhibited at ‘The Salon’ in the Louvre, Paris from 1840 and following the success of his painting ‘Romains de la Decadence’ in 1847, he was commissioned to paint three major historical pieces.

This included ‘The Enrollment of the Volunteers of 1792’, commissioned by the French government, and ‘The Baptism of the Prince Imperial’ commissioned by the Imperial family, as well as murals of religious scenes in the church of Saint-Eustache.

Unfortunately, Couture did not complete the commissions for the government or the Imperial family and his paintings of the church murals were not well received. Disheartened, he eventually left Paris in 1860, going back to Senlis before moving on to Villiers-le-Bel.

Away from Paris, he distanced himself from the art scene and instead focused on teaching and giving advice to other artists, painting more portraits rather than historical pieces.

Couture opened his own atelier and published his teachings, most famously in a book in 1867 that he titled ‘Méthode et entretiens d’atelier’ or Methods and maintenance of the workshop. This work included the use of rough drawings and quickly drawn sketches called ébauche in final pieces. He also gave instructions for how to achieve his signature tones and effects.

In doing so, Couture was intentionally challenging the academic establishment by making his methods available to all. Prior to 1863, the École, where aspiring French artists were expected to go to learn and study, did not teach painting or sculpture as they wanted to have complete control over the education of arts.

Couture did not agree with this and instead openly taught students his methods, techniques and processes before publishing them in his book for all to read.

Couture’s teaching attracted international students from Germany, America and Scandinavia. Success in his later career came mainly from selling small paintings to American collectors who first heard of Couture and saw his work through the study materials of his American students. Exposure to this foreign market granted him success despite the inadequacies of his work in his own country.

5. Legacy

Couture died in 1879 at Villiers-le-Bel where he lived out the later period of his life.

His published teachings are the most detailed of the time, providing a rare insight into the techniques and processes used. His quick painting method influenced many future artists before being used by the Impressionists.

In contrast to many painters who are now considered famous despite their work being relatively unknown during their lifetime, Couture is not well-known today despite achieving considerable academic success, albeit briefly.

It can be deduced that his inability to finish the two great commissions and the rejection of his church murals cost Couture his place in history.

His name has certainly not been remembered in the same way many of his contemporaries have. However, perhaps this is in keeping with the way he lived his life. When asked to write an autobiography he said, ‘Biography is the exaltation of personality, and personality is the scourge of our time.’