1. The ‘Poplars’ Series

After adopting the Seine River as one of his main effigies, Monet pushed his work farther by focusing on the brooks and banks of these iconic watercourses.

His ‘Poplars’ series is a continuation of his fascination with naturalistic scenes, painted ‘en plein-air’ with the archetypal Impressionistic technique.

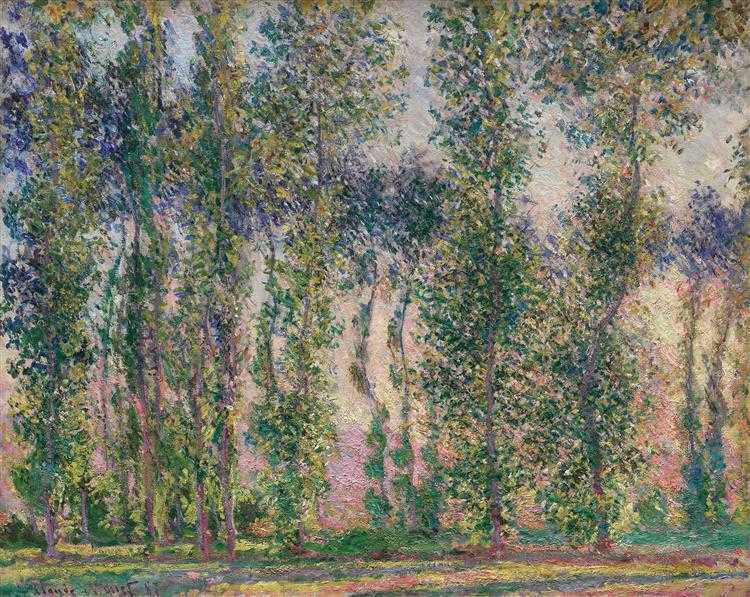

| Title | Poplars in the Sun |

|---|---|

| Year | 1887 |

| Dimensions | 74 x 93 cm (29 x 36.5 in) |

| Current location | Staatsgalerie Stuttgart |

| Title | Poplars at Giverny |

|---|---|

| Year | 1888 |

| Dimensions | 74 x 92 cm (29 x 36 in) |

| Current location | Museum of Modern Art |

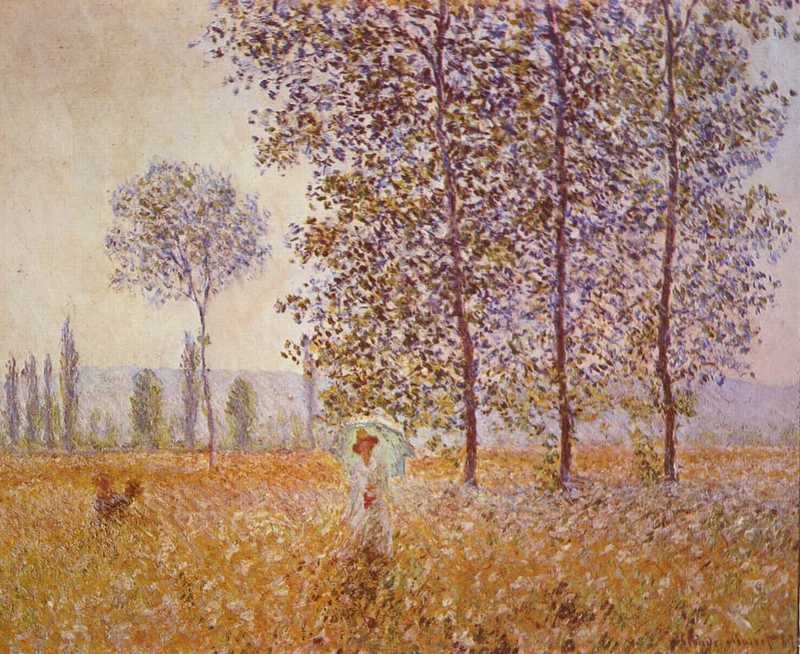

| Title | Poplars in the Sun |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 93 x 73.5 cm (36.5 x 29.5 in) |

| Current location | National Museum of Western Art |

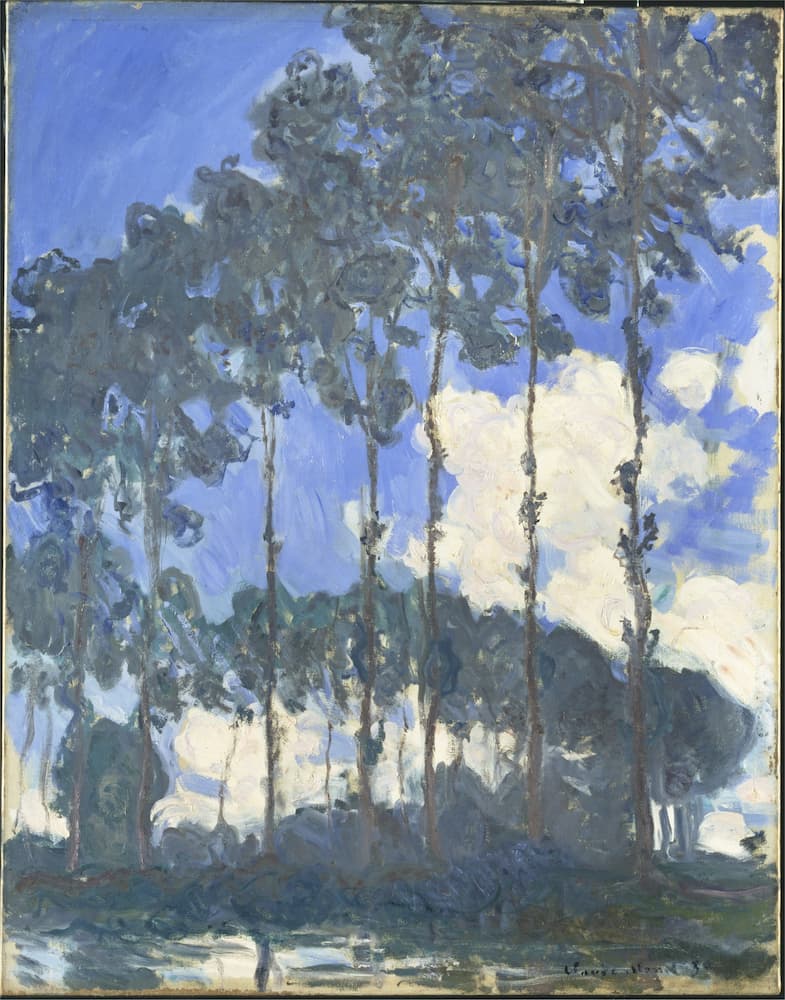

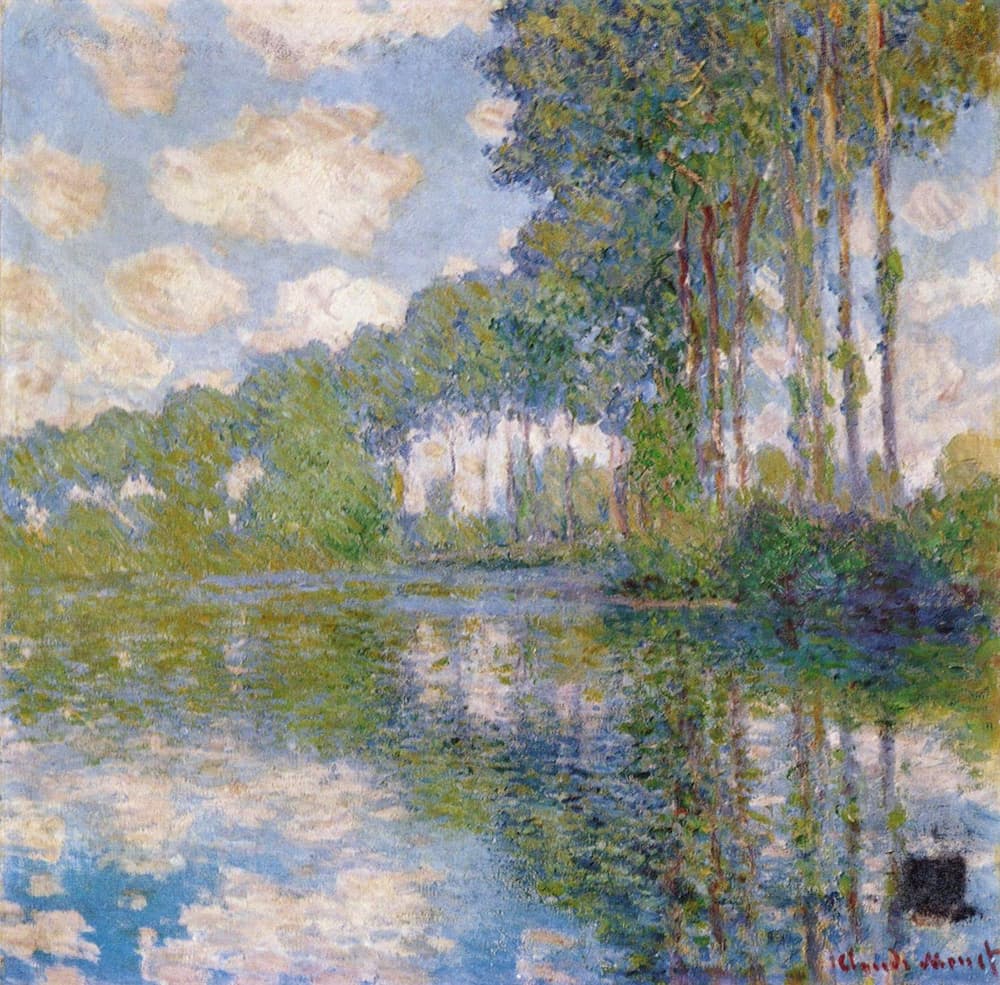

| Title | Poplars on the River Epte |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 92 x 73 cm (36 x 29 in) |

| Current location | Tate Britain |

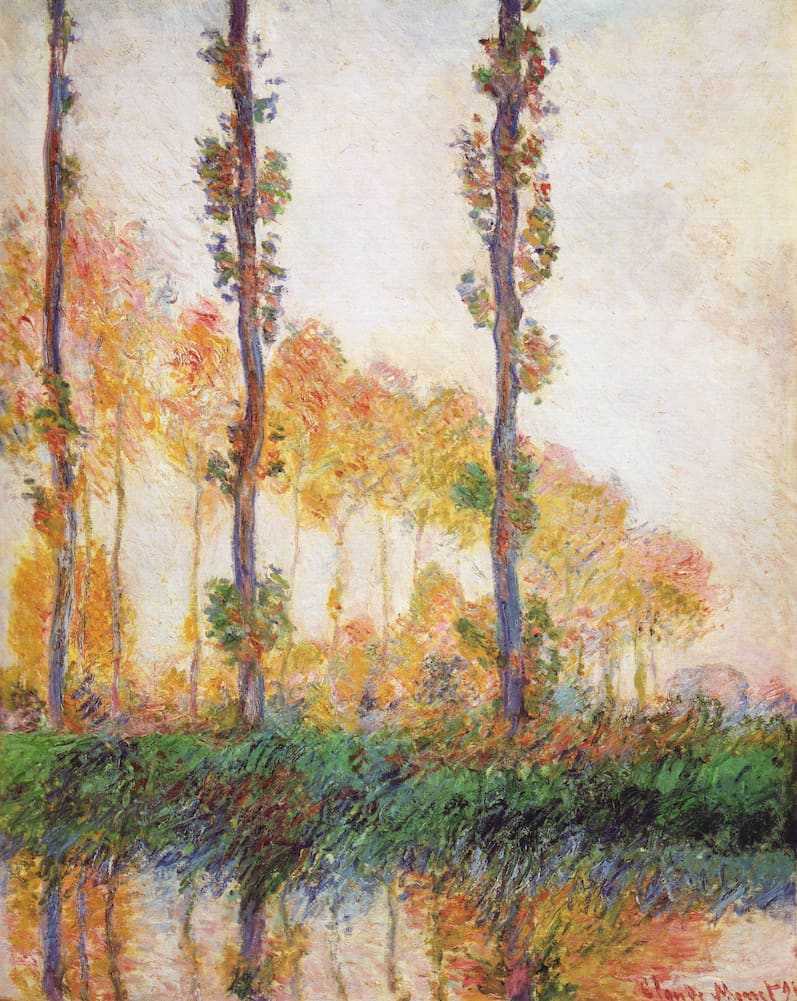

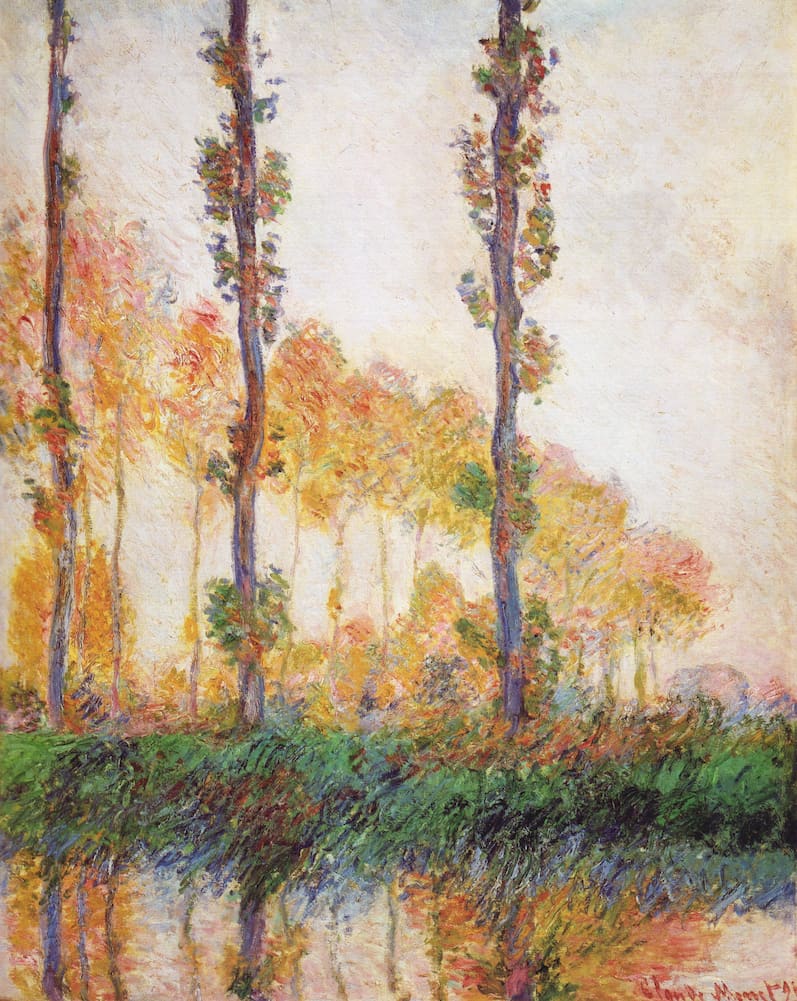

| Title | Poplars (Autumn) II |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 92 x 73 cm (36 x 29 in) |

| Current location | Philadelphia Museum of Art |

| Title | Poplars at the Epte |

|---|---|

| Year | 1900 |

| Dimensions | 82 x 81 cm (32 x 31.5 in) |

| Current location | Scottish National Gallery |

| Title | Poplars (Autumn) |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 92 x 73 cm (36 x 29 in) |

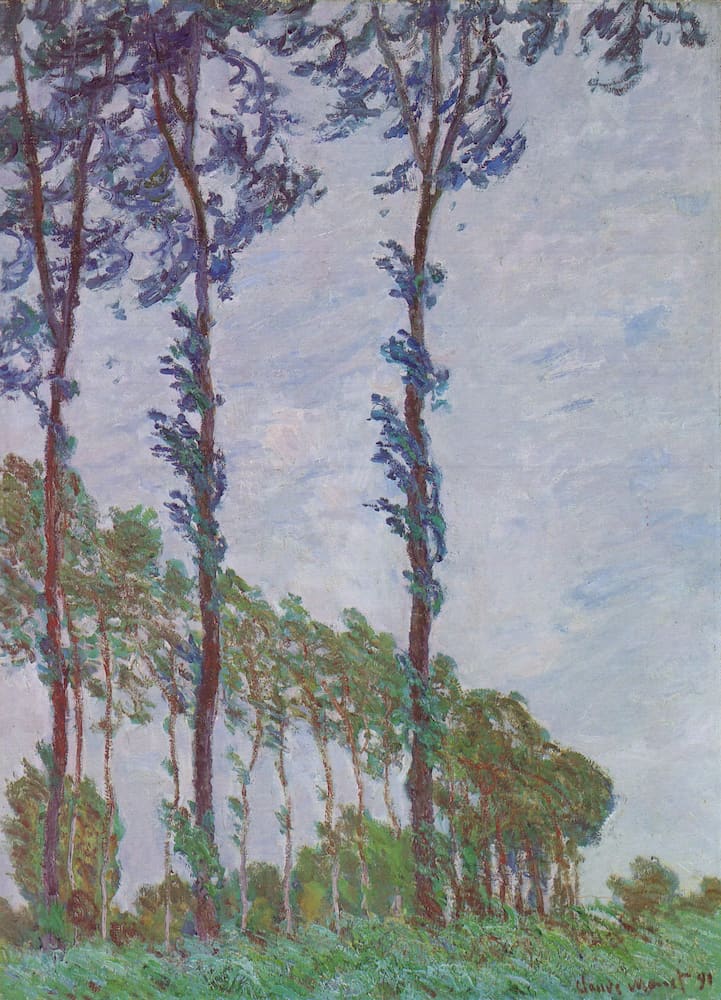

| Title | Poplars (Wind Effect) |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 100 x 73 cm (39x 29 in) |

| Title | Three Trees in Grey Weather |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

2. What is the current value of Claude Monet’s ‘Poplars’ series?

In recent years, Monet has consistently made headlines for crafting some of the most expensive examples of art ever sold at auction. The ever-popular ‘Poplars’ series continues this trend. In 2014 it was recorded that bids for Monet’s artwork had arrived from 19 countries from across the world.

In 2015, an individual painting from the group was valued between £9 million and £12 million. However, in 2011 ‘Les Peupliers’ went beyond this boundary, fetching an impressive $22 million at auction. To date, this is still the highest price paid for a piece in Monet’s ‘Poplars’ series.

3. ‘Poplars’ 1887 – 1900

Working on location, Monet created compositions that complimented the lighting conditions available on the day he was painting.

With oscillating levels of sunshine, Monet uses colour to prescribe a sense of temperature in the Poplars series; oranges are added to denote heat whilst murky blues symbolise cold. In addition, Monet excludes white or black when interpreting highlights and lowlights, instead opting for a similar colour palette of pastels and warmer or cooler tones.

In the works, he employs animated mark-making with dots, dabs and dashes. First, Monet applies a simplistic wash of colour, cementing a subdued backdrop.

Then clouds appear as pearls in the sky, shaped using pasty daubs of paint. The trunks of the trees are stretched out thinly, like a spine supporting the poplars’ columnar bodies. Spots of green, grey and brown mediate the mass of leaves. At the poplars’ roots, vivid shades are streaked across the canvas, showing the movement of water as the river runs.

These marks indicate the transition from Impressionism into Post-Impression in Monet’s work: his speckled brushwork in these paintings formed the foundation for future painting styles, such as Pointillism. Monet himself described the mathematical quality of his canvases, stating “here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow.”

By distributing different types of brushstrokes across the canvas, texture is defined within the piece. With the months bringing different weather conditions, this was all the more important to Monet’s practice. In one image, shrubs bend, suggesting a blowing breeze. In another, a female figure is seen strolling through a golden field, holding a parasol aloft. The cream of her dress is the only bright burst of pale paint throughout the whole of the ‘Poplars’ series, demonstrating how seriously Monet took colour-mixing. Whether using dusky darks or pastel hues, each installation of ‘Poplars’ is both analogous and unique to its neighbour.

4. What was Monet doing when he painted the ‘Poplars’ series?

After the tragic death of Monet’s first wife, Camille, the artist’s finances dropped dramatically.

Soon after, in 1879, he travelled to Paris, hoping to generate a new wave of attention for his work. Instead, he found that modern times were moving away from the Impressionists. This revelation, combined with his all-consuming grief, led Monet through a dark period wherein he expressed a wish to move away from art altogether.

On a journey from Vernon to Gasny, Monet absent-mindedly watched the countryside speed by from his train window. In an instant, inspiration struck. On the horizon, he witnessed miles of picturesque scenery: steadfast temptation for any Impressionist. The landscape was in fact Giverny, a quaint commune in the northerly region of Normandy.

At Giverny, Monet decided to rent a house and gardens in the area. Over time, the prettiness of the surrounding scenery helped him fully reclaim his passion for art and Impressionism. Due to his dwindling funds, Monet moved in with his friends Ernest and Alice Hoschedé and their five children, along with his own two sons mothered by Camille, Jean and Michel. Ernest was a useful figure for the artist to have around as he was a patron of Monet’s, collecting and commissioning his artwork for many years.

Monet and Alice grew close as well; it is thought that her sixth child, Jean-Pierre, may have been fathered by Monet. Following this revelation, a newspaper of the era, ‘La Gaulois’, wrongly published that Alice was his “charming wife” in 1880. In fact, Alice went on to marry Monet in 1892 after Ernest’s death. The coupleremained in Giverny where their children were educated at the local schools.

5. The Gardens at Giverny

For 43 years, Monet’s home in Normandy provided him with endless inspiration.

Along with the aid of professional gardeners, he and the Hoschedé family designed the back garden, planting over a thousand flowers, with some species being imported from Egypt and South Africa. During the renovation Monet said, “I must have flowers, always and always”. The excavation paid off and in full bloom the garden was a colourful spectacle to behold.

Monet reportedly wrote daily instructions to his landscapers, designing layouts and consulting with architects to fashion the space for his creative mind. Through the grounds, Monet set up easels to explore the same space from different angles. He also had two major studios onsite: the first, a former barn, and the second, a tall workspace with skylights to let in the natural light.

Monet has a method of letting us into his life through his paintings. He has strewn repeated motifs of the house and its orchards throughout his illustrations. Claude Monet fans will easily recognise the curved Japanese bridge, the majestic weeping willow and floating blossoms from some of his most famous works.

This, paired with his temporary break away from the other Impressionists, led to Monet testing his talents at portraying the same scene in different conditions. Over the coming decades, Monet created numerous series experimenting with this technique.

After purchasing part of a water meadow, the Epte River was incorporated into the back portion of Monet’sgarden. This encouraged the artist to venture outside of his own residence, spying out interesting locations further afield. In doing so, the poplar tree became a chosen and common theme in Monet’s oeuvre, leading to the series we know and love today.

6. Changing perspectives on the ‘Poplars’

The ‘Poplars’ series’ popularity is thanks to more than just its picturesque appearance.

After Monet died, hisestate was left to his son Michel. It was then passed to Monet’s second son, Jean Monet, and to his widow, Blanche Hoschedé. When the inheriting line eventually ceased, the house was gifted to the Académie de Beaux-Arts. Thanks to a vigorous restoration effort, the property has now been turned into the Foundation Claude Monet.

Monet’s Foundation was almost entirely funded by money from abroad: it is estimated that $7 million was sent from America during the 1970s. This goes to show how important Monet’s work is worldwide. In 2010, hishouse at Giverny received over 530,000 attendees, making it one of the most popular tourist attractions in northern France!

One of the main collections referenced at the Foundation Claude Monet is his ‘Poplars’ series. Near to the rejuvenated gardens, the original spot where the poplar trees stood is still abundantly populated by plants today. Noting this context, Monet’s artwork becomes even more enchanting to the contemporary spectator. Despite the century-long gap, the landscape has barely changed at all. Consequently, Monet’s ‘Poplars’ presents images of nature’s everlasting power; the notion that flora and fauna can overcome man madeinterventions.

The Impressionist’s naturalistic scenes could account for almost any period of human history, yet their depictions of people and buildings are forever bound to their time. When we view one of Monet’s ‘Poplars’, we could just as easily be viewing a twenty-first century painting of a line of trees in any stretch of countryside. This shows the true timelessness of Monet’s creative mission - and may be one of the reasons his paintings remain so popular today.