1. 15,000 BC-1503 AD: Caves to Mona Lisa

(1) Caves are painted in France

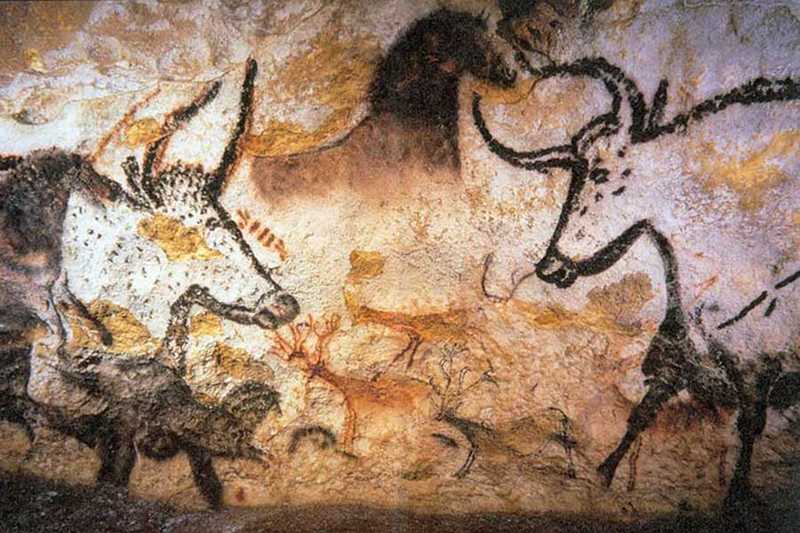

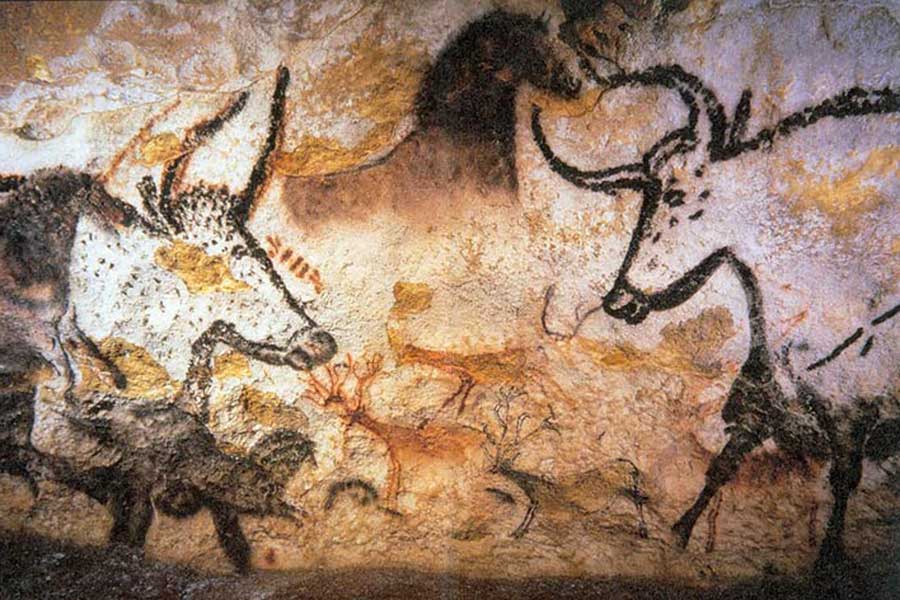

15,000 BC Successive generations living in the Dordogne in France produce 600 paintings on the walls and ceilings of the Lascaux Caves. The paintings contain nearly 6,000 images, comprising humans, animals (including 264 horses and 90 stags) and abstract signs. The paintings were made using mineral pigments – from compounds such as iron oxide, hematite and goethite – which were dabbed on, rather than painted by brush. The most famous section is called the Hall of the Bulls, which also features horses, stags and a single bear. One of the bulls is an impressive 5.2 metres long. Remarkably, the caves were discovered by accident by a schoolboy walking his dog in 1940! Sadly, the caves were closed to the public in 1963 on conservation grounds. They were awarded UNESCO World Heritage status in 1979.

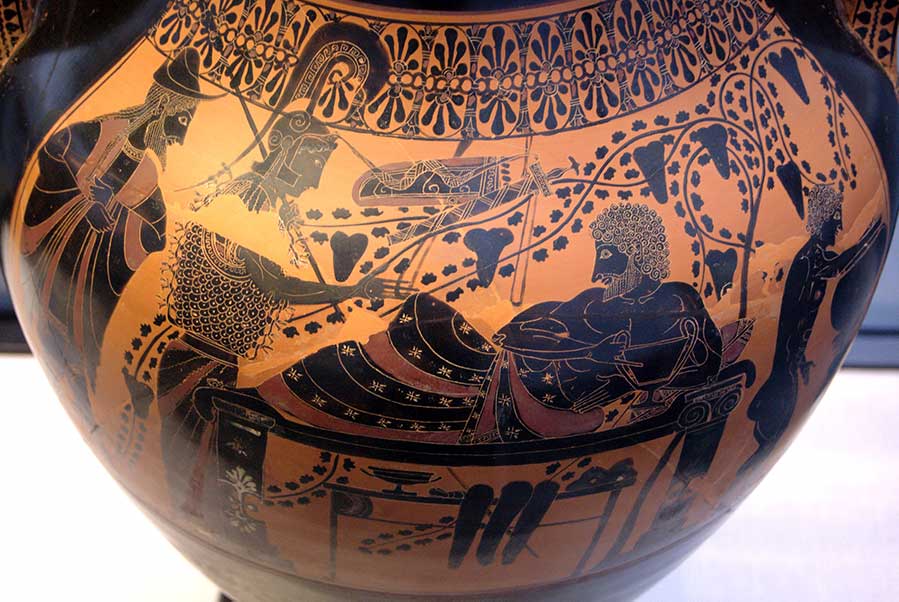

(2) The Greeks paint people

1000 BC - 100 BC Artisans in Ancient Greece produce pottery, sculpture and (most prestigiously) panel paintings. Though not much Greek panel painting survives, owing to the instability of the pigments used, pottery painting gives an idea of the types of works that were created. Greek artists tended to focus on the human body, often in idealised and naked poses. A good example is the above amphora (jug), now housed in Munich’s Antiquities Museum, dating from 520-510 BC.

(3) The Romans copy the Greeks

100 BC - 565 AD Roman art follows on from, and is heavily influenced by, Greek art. As with ancient Greece, sculpture and especially panel painting were highly prized. But the Romans painted more diverse subjects than the Greeks, including landscapes, still lifes, portraits and triumphal scenes. As with Greek art, not much of the painting survives. A good remaining example is the above landscape taken from the Villa of Agrippa and now housed in Naples’ National Museum of Architecture. Classical art is art produced by the Greeks and the Romans, during the 'classical period'. It came back into fashion in the second half of the 18th century, popularised by neo-classicists like Ingres.

(4) The Medieval period: churches get decorated

500 – 1500 The Medieval Period started with the decline of the Roman empire in about 500 AD, and lasted until the Renaissance (the ‘rebirth’ of classical ideas and styles) in about 1500. It is best known for its detailed and richly decorated religious art. Gold was often used, together with ivory and the pigment ultramarine (made from lapis lazuli mined in Afghanistan). Whilst some secular art was produced, churches definitely provide the most impressive remaining examples of medieval art. They include the glittering altar of the Cathedral of Monreale in Sicily (above).

(5) The Renaissance: Da Vinci paints the Mona Lisa

1503 Leonardo da Vinci, a polymath who revolutionised fields as diverse as painting, anatomy and mathematics, starts work on his most famous painting: the Mona Lisa. Commissioned by Lisa’s husband, da Vinci kept the work with him until his death in 1519 – never quite finishing it. The Mona Lisa is a really small painting that became the world’s most famous work in 1911 when it was stolen from the Louvre (the security was so lax that they didn't realise it had gone for 24 hours!). An Italian national named Vincenzo Peruggia was responsible, getting caught when he tried to sell the painting to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Learn more on our World's Top 10 Paintings page.

2. 1512-1838: Sistine Chapel to Turner

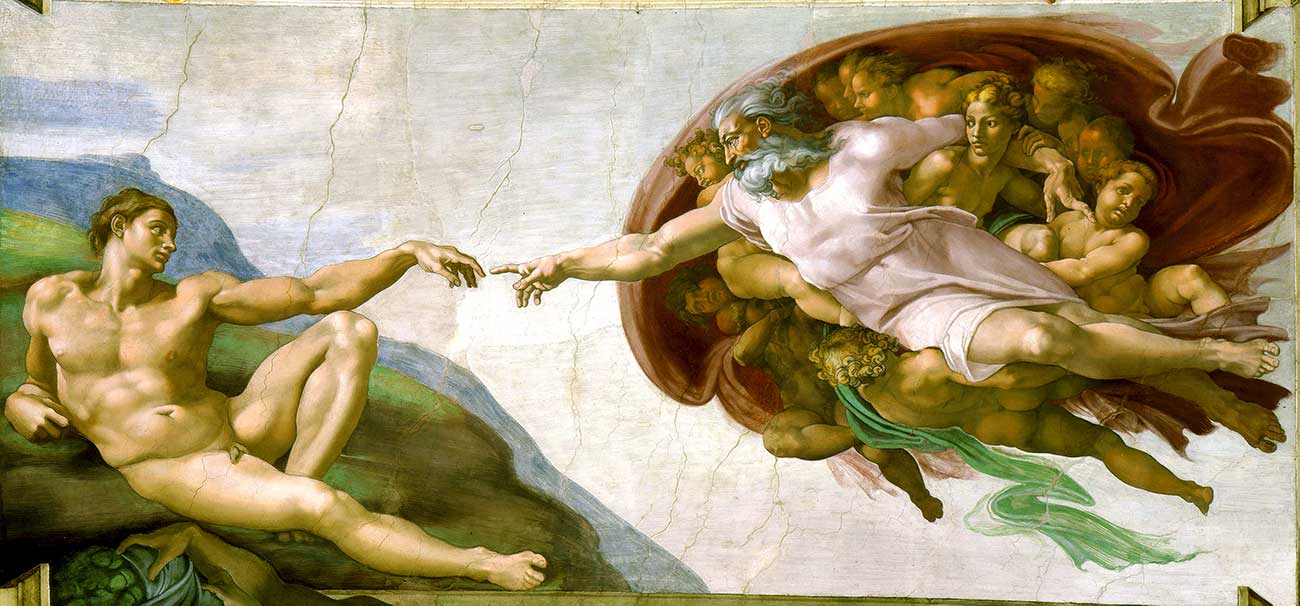

(6) The Renaissance: Michelangelo decorates the Sistine Chapel

1512 Michelangelo, the 16th century’s other genius, finishes his decoration of the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling. His masterpiece, painted into freshly laid plaster, depicts nine scenes from the Book of Genesis. The most famous part of the fresco – The Creation of Adam – shows God’s outstretched index finger nearly touching Adam’s finger. It is the most reproduced work in western art. Oh, and by the way, Michelangelo managed this feat a mere eight years after he finished chiselling away on the world’s most famous sculpture: the 17-foot-high marble depiction of the biblical (and very buff) David.

(7) The Baroque Era: Rembrandt paints the Night Watch

1642 Rembrandt, the leading painter of the Dutch Golden Age (part of the Baroque era), finishes his most important work: The Night Watch. This is a huge (363 x 437 cm) and varied work, depicting a group of militiamen getting ready for combat. The scene is riotous: centred around their captain, the militiamen are cleaning their rifles (one rifle has gone off accidentally!), pointing pikes in all directions, waving a military standard, and beating a drum. No wonder there is also a barking dog. Rembrandt, though, had a sad end: he was a spendthrift, made bankrupt in 1656, and buried in a pauper’s grave.

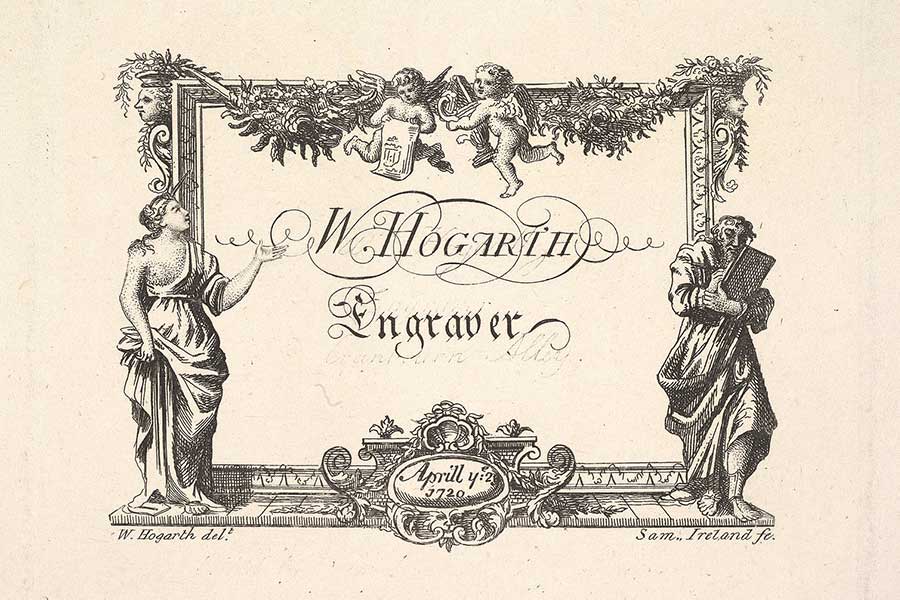

(8) Artists get copyright protection

1735 The first modern copyright legislation to protect artists, the Engravers Copyright Act 1735, was passed in the UK. Copyright had previously protected authors only, with this act – often called Hogarth’s Act after English painter William Hogarth – extending protection to engravings. Paintings, sculptures and other artworks were later added to the 1735 Act, the essential features of which resemble much modern copyright legislation.

(9) Constable paints The Hay Wain

1821 The British landscapist John Constable completes The Hay Wain, a painting of a wagon carrying hay crossing a shallow river in Sussex. Though we might think of this as a traditional scene, the painting has two radical elements: it captures everyday life (and not religious, mythological or historical scenes); and it contains the most breath-taking clouds as an element of the composition in their own right. Though reviews when the painting was exhibited at London’s Royal Academy were good enough, the painting caused a sensation when shown in Paris’ Salon. French King Charles X awarded Constable a gold medal. And, more importantly, the picture inspired the realist movement and even some of the impressionists.

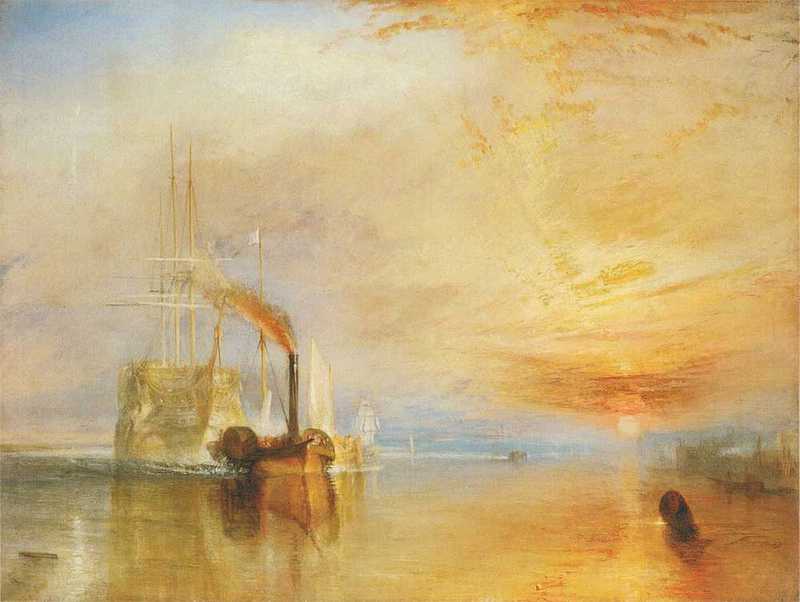

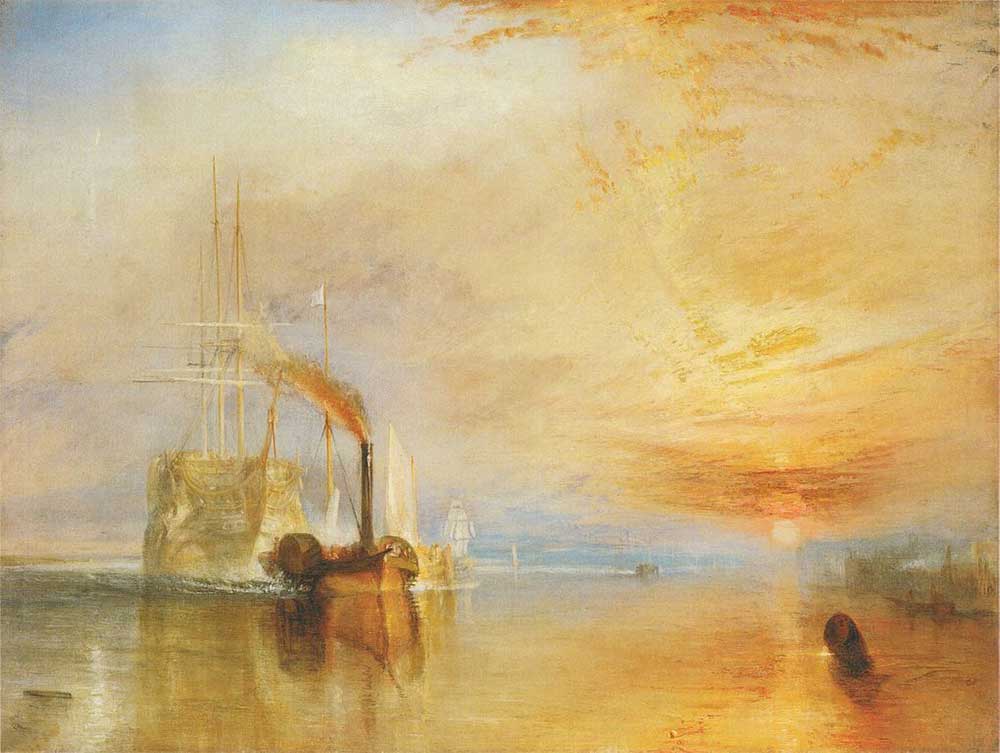

(10) Turner's paints The Fighting Temeraire

1838 JMW Turner was a child prodigy, enrolling at the Royal Academy of Arts at the age of 14 and exhibiting there the next year. He was difficult, reclusive and even downright eccentric - rowing a boat into the middle of the Thames so that he couldn't be counted in the 1841 census. But Turner was also brilliant, in particular when he was painting light. The Fighting Temeraire, often voted the UK's most popular and important painting, is the classic example of this. Painted in 1838, it shows the eponymous battleship - which distinguished itself at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 - being towed to a breaker's yard to be scrapped. Monet was inspired by the painting in 1871, when he briefly lived in London after fleeing the Franco-Prussian war.

3. 1841-1886: Paint tubes to van Gogh

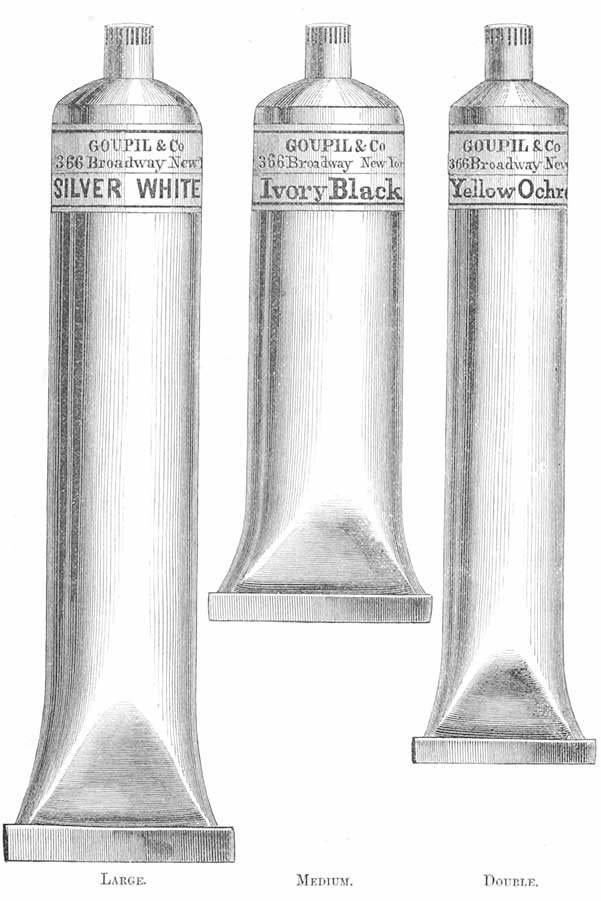

(11) The collapsible paint tube is invented

1841 So far in our timeline, art was typically produced in workshops or studios using paint that was both unstable and laboriously made up from powder before an artist could start work. John Rand’s invention of the collapsible paint tube, initially made of lead or tin, changed all that. Paint could be freely transported; and artists could choose the colour they wanted at a moment’s notice. As Renoir put it:

“without colours in tubes, there would be no Cezanne, no Monet, no Pissarro, no Impressionism.”

Rand’s invention was swiftly followed by others, most importantly the collapsible easel, which allowed painters to set up a studio wherever they pleased.

(12) French art gets stirred up

1863 The French Emperor Napoleon III decrees that a special exhibition of artwork that had been refused entry to the official French Salon (the exhibition hosted by the Academy des Beaux Arts) should take place. The exhibition, known as the Salon des Refuses (the Exhibition of the Rejected) featured a work by Edouard Manet called Dejeuner sur l’Herbe. On any view, this is an odd composition: there are two well-dressed young men; one naked woman in the foreground; and a partially clothed woman in the mid-ground (she appears to be washing). To the French public, however, the work was an abomination: the public jeered, even attacking the painting with canes and umbrellas; and the critics were ferocious in their condemnation. But Manet did not give up – in fact, the notoriety spurred him on. And his resolve inspired painters like Monet, Renoir, Cezanne and Degas to continue working on their new brand of art – impressionism.

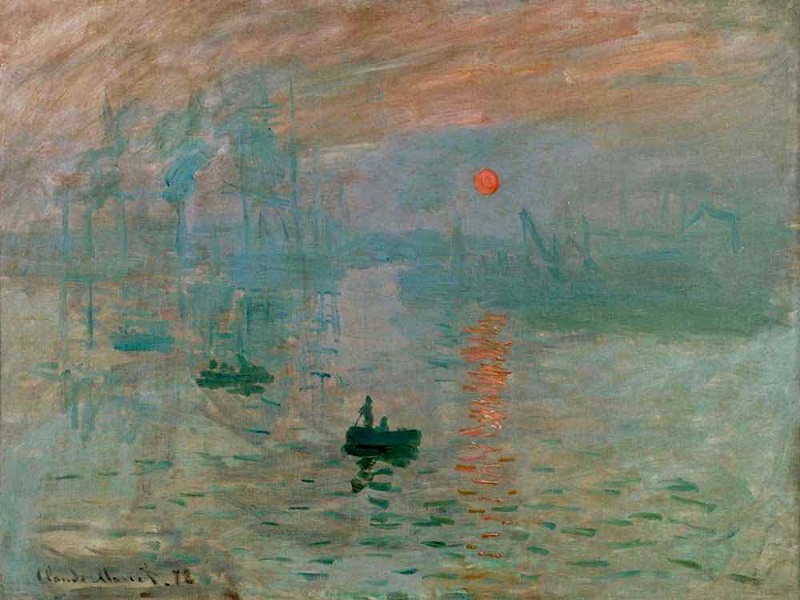

(13) The Impressionists go their own way

1874 The first impressionist exhibition is held in Paris. Led by Monet, Renoir, Degas and Pissarro, the impressionists had got fed up of being rejected by the conservative art establishment and decided to put on their own show. They made few sales and the reviews were horrific, for example when Louis Leroy described Monet’s Impression: Sunrise as

“wallpaper in its formative state”.

Leroy also coined the phrase ‘impressionism’, intended as an insult. But the first impressionist exhibition, which was followed by seven more shows, showed the world that the Impressionists were not going to back down: their style of art was here to stay.

Interesting fact...

Camille Pissarro was the only impressionist to exhibit in all eight of the impressionist exhibitions.

(14) Monet moves to Giverny

1883 Claude Monet, the most important and prolific of the Impressionists, moves to Giverny. Monet would later buy the house that he initially rented and install a water lily pond on its grounds, which he painted in his most important series of works: over 250 different Water Lilies. Monet’s lilies became larger and more abstract as the decades went on (he was still painting in 1926, the year of his death), with the largest of all – canvasses measuring 2 x 6 metres – now installed at the Musee de l’Orangerie in Paris. These days, Monet’s works change hands for at least tens of millions of dollars. Not bad for a man who spent long periods in the 1860s and 1870s on the breadline.

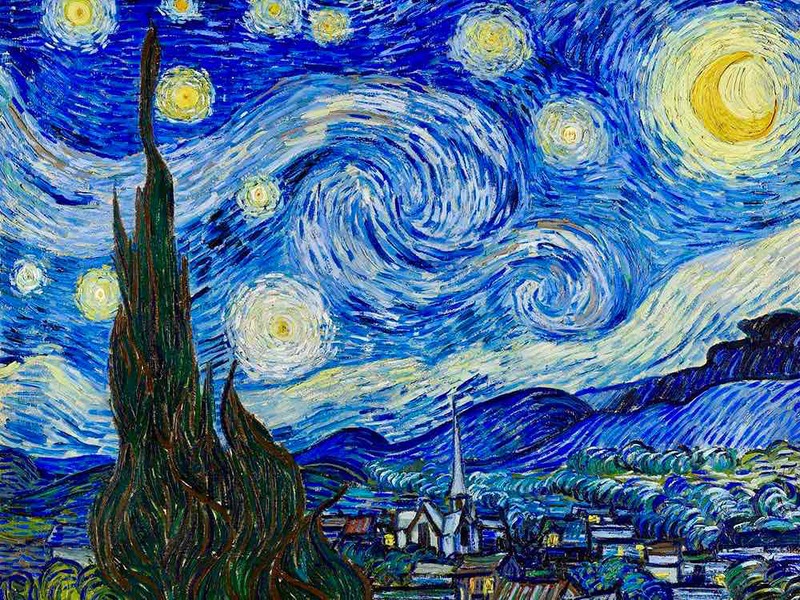

(15) The Impressionists inspire van Gogh

1886 Vincent van Gogh, who had previously painted in earthy tones, moves to Paris and starts socialising with the Impressionists. He begins to experiment with bolder brush-strokes and a lighter and brighter palette. And thus began the period of five years, ending in his premature death in June 1891, in which van Gogh produced the hundreds of bright, bold and striking works for which he is best known. They included Starry Night, Sunflowers, Wheatfield with Cypresses, various Self-Portraits and van Gogh’s wonky-looking bedroom at the house he shared with Gauguin in Arles.

4. 1886-1937: Pointillism to Guernica

(16) Seurat founds Pointillism

1886 Georges Seurat, the founder of the pointillist movement, finished his most important work: A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. This ten-foot-wide work shows bathers, dogs and even a monkey lounging on the banks of the Seine. But, more importantly, it showcases Seurat’s new method – pointillism – a system of constructing a painting using thousands or even millions of dots of contrasting colours. The technique, also known as neo-Impressionism or Divisionism, relies on the ability of the mind to blend colours together to produce a larger colour palette. Paul Signac was pointillism's other key exponent.

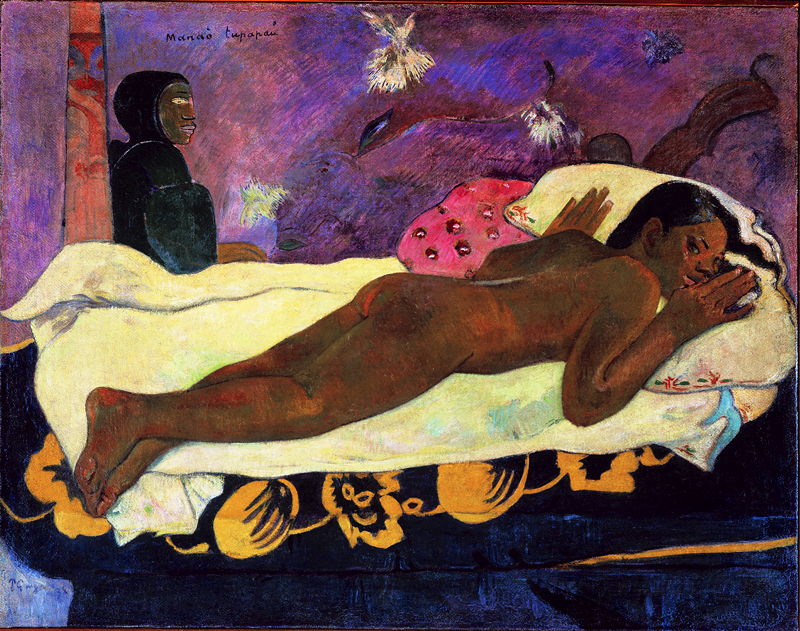

(17) Gauguin sets sail for Tahiti

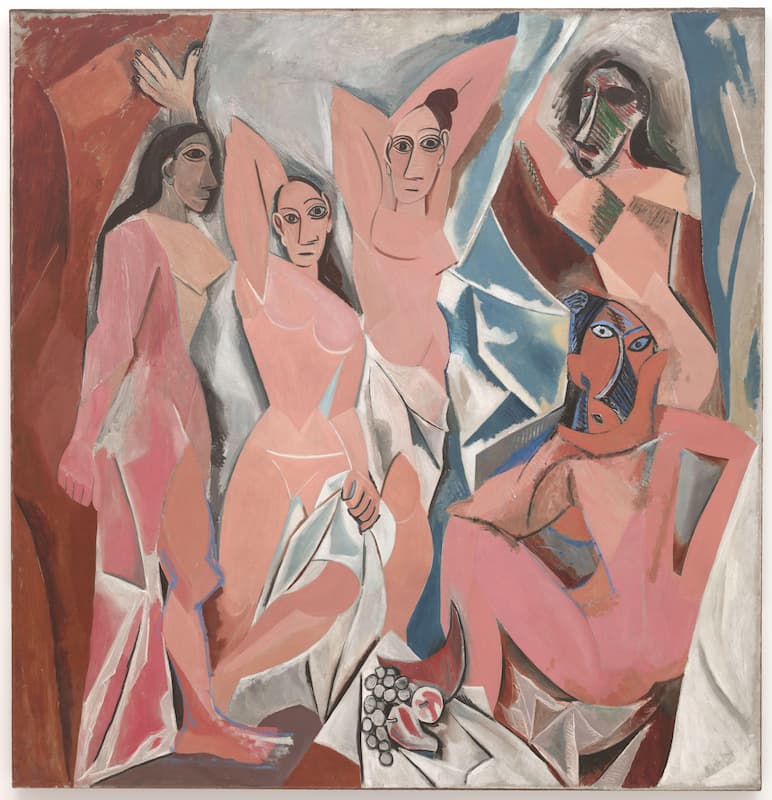

1891 Paul Gauguin, the stockbroker turned painter, leaves for Tahiti to add a new dimension to his art. Gauguin was already an artist of some repute, having famously quarrelled with van Gogh in the Arles house they shared together on 23 December 1888 – an argument that led to van Gogh cutting off part of his left ear. But Gauguin’s pursuit of fresh experiences in a “primitive and savage world” made an indelible mark on his works: they became bolder, less naturalistic and started to include symbolism. Gauguin was a profoundly troubled and controversial artist: he was an egomaniac who abandoned his wife and five children to go to Tahiti, where he took three teenage brides and gave them syphilis. But Gauguin was also a major influence on the young Pablo Picasso, who saw his Gauguin's works at a posthumous exhibition whilst working on his first masterpiece: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

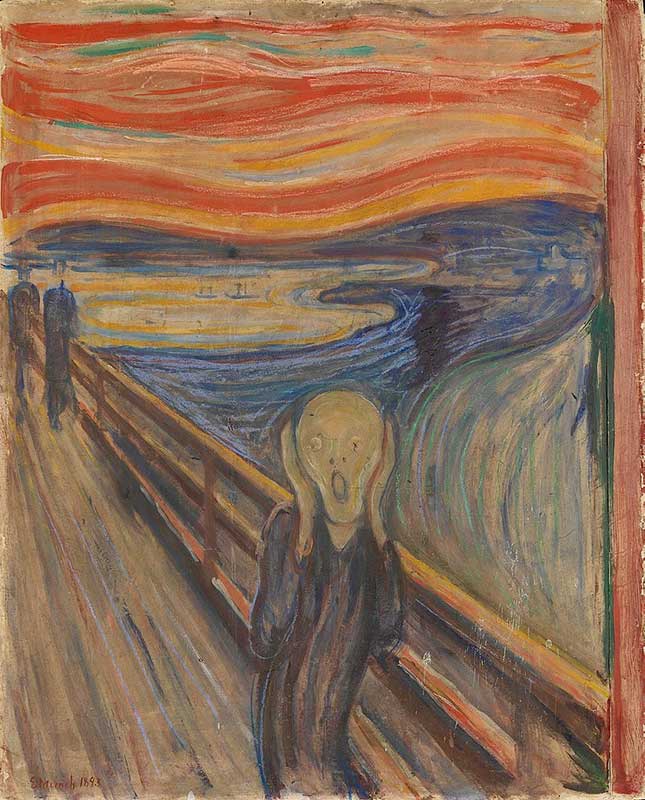

(18) Munch paints The Scream

1893 Edvard Munch led a painful life: his mum died when he was five, his sister when he was 13, and his dad was both highly religious and very nervous. Munch was later to comment that

"the angels of fear, sorrow, and death stood by my side since the day I was born".

But perhaps this suffering was necessary for Munch to be able to produce The Scream: a poignant, haunting and frankly disturbing work depicting an androgynous figure covering its ears against what Munch said was the "infinite scream passing through nature". The painting, which has become an iconic work, certainly captures the strains, uncertainties and paradoxes of human existence.

(19) Picasso and Braques invent cubism

1908 The term cubism is coined, probably by Henri Matisse and intended as an insult (he was hurt that his former protégé Georges Braques had started working closely with Picasso). It refers to art that deconstructs perspective and often depicts objects as if they are made of small cubes. Indeed, the subject of the painting is often barely perceptible, having been shattered into various different forms and angles. Both Braques and Picasso, whose works over the next five years were difficult to distinguish, disliked the term ‘cubism’ but felt obliged to use it.

(20) Picasso paints Guernica

1937 Pablo Picasso, the most important artist of the 20th century, produces the century’s greatest work: Guernica. This harrowing scene depicts the carnage following the German and Italian bombing of the eponymous Spanish mountain town on market day during the Spanish Civil War. The figures captured by Picasso include a woman clutching her dead child screaming to the heavens and a horse with a lance run through its torso. The canvas is huge (349 x 776 cm) and is all the more haunting because it is black and white (Picasso experimented, but ultimately rejected, the use of colour). A full-sized tapestry of the work was hung in the UN’s Security Council room for over three decades.

5. 1948-2011: Pollock, Warhol and Hirst

(21) Pollock splatters paint

1948 Jackson Pollock paints Summertime: 9A and several of his other best-known works. Pollock’s artistic journey was not smooth, with many saying that his work wasn’t art at all. But his seemingly random compositions, often completed by dripping paint onto the canvas, catapulted him to fame and riches as the leader of the abstract expressionist movement. Pollock had a little help from his friends, and it seems the CIA – who wanted to promote free art for the free world in the aftermath of the second world war and the threat of communism. Sadly, Pollock died in an alcohol induced car crash in 1956 aged just 44.

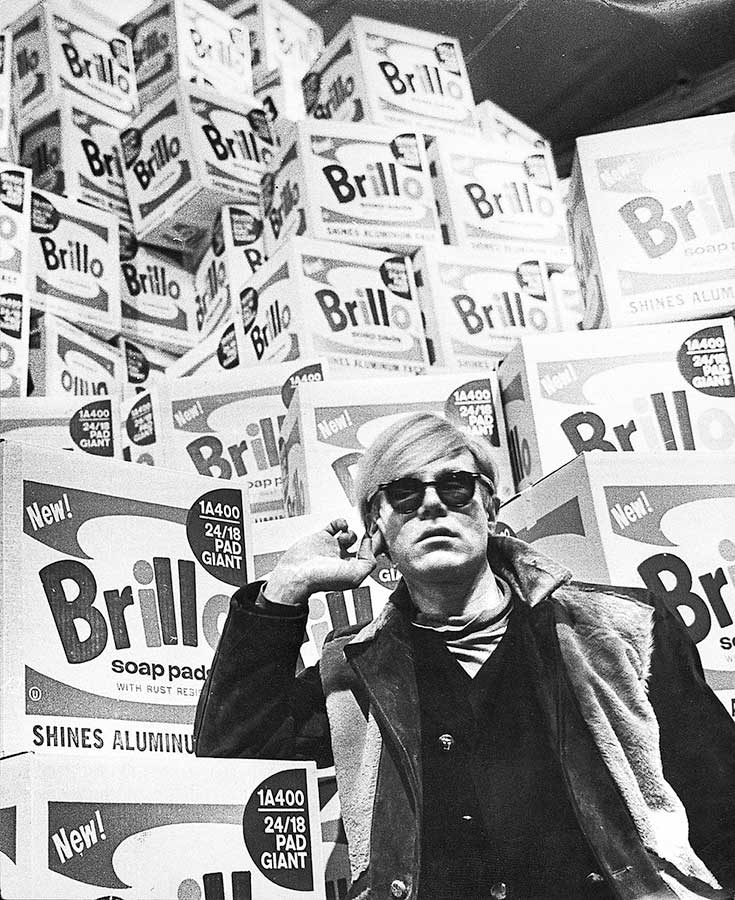

(22) Warhol paints soup

1962 Andy Warhol shocks the art world by producing 32 individual canvasses each representing a different variety of Campbell’s soup. Warhol actually paid his friend Muriel Latow $50 for the idea. She said:

“You should paint something that everyone sees every day, that everyone recognises like a can of soup.”

Warhol always rejected the notion that his works were an attack on capitalism. He instead characterised them as a celebration of American culture: “the richest consumers buy essentially the same thing as the poorest”. What can be said with certainty is that Warhol’s Soup Cans were a defining moment in the pop art movement – art which takes its images from popular culture, such as advertising, comics or mass-produced household items.

(23) Magritte gets surreal

1964 Rene Magritte, one of the leading members of the surrealist movement, produces The Son of Man – a painting of a businessman with his face obscured by an apple. Surrealism depicts illogical, unnerving or plain weird scenes in an attempt to engage the unconscious mind. Some people find it profound; others just don’t get it. Whichever camp you fall into, it cannot be denied that surrealism has been embraced by popular culture. The Son of Man, for instance, features heavily in the Pierce Brosnan/Rene Russo film The Thomas Crowne Affair.

(24) Hirst blings it up

2007 Damian Hirst finishes For the Love of God, a platinum cast of a real human skull encrusted with 8,601 flawless diamonds (themselves valued at c. £12 million). The work was exceptionally controversial: one critic described it as celestial; another said it was vulgar; and one of Hurst's friends accused him of plagiarism. But the publicity that accompanied the work, together with its unusual nature, cemented Hirst's position as one of the world's most important modern artists. Hirst's other works include a Tiger Shark submerged in formaldehyde (called The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living).

(25) Riley gets optical

2011 Bridget Riley, the English artist known for her optical illusions (aka Op Art), is honoured with a show in London's National Gallery. Riley was born in 1931, taught art for about a decade, and was heavily influenced by Seurat's pointillism. She is best known for her black and white Op Art, using geometric shapes to disorient the viewer. These days, Riley splits her time between London, Cornwall and a studio in Provence, France.