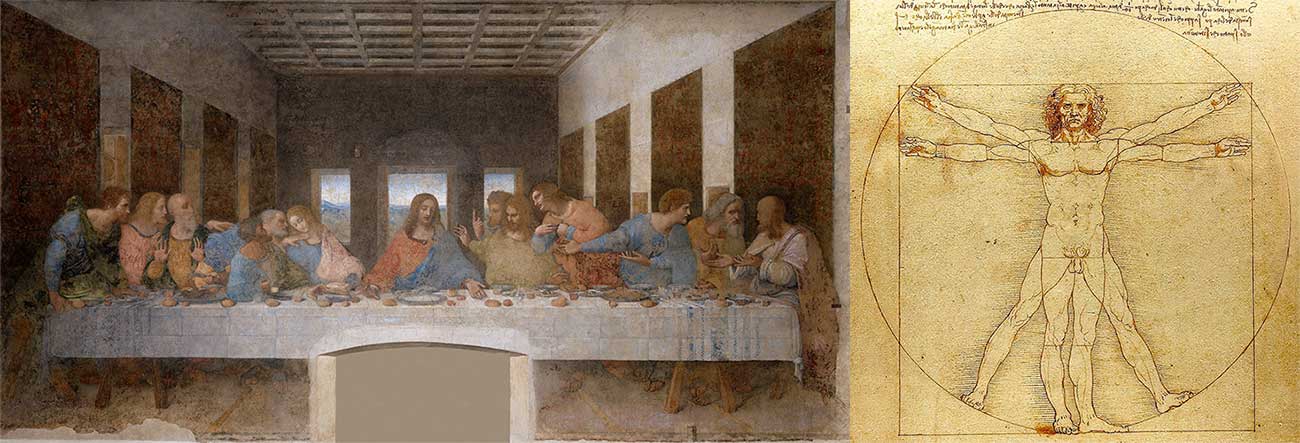

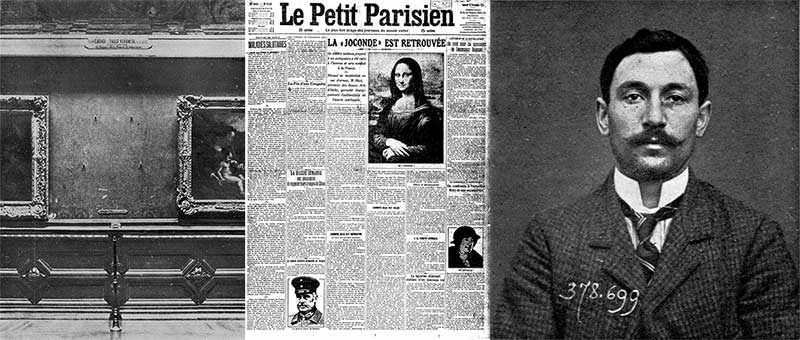

1. Mona Lisa - Leonardo da Vinci - 1503-1519

Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa is the reason that eight out of ten visitors flock to the Louvre in Paris.

Top 5 facts

(1) Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was a polymath (an expert in various subjects). His interests included anatomy/dissection, astronomy, botany, geology, mechanics, optics, painting and poetry. He used his knowledge of anatomy to get Mona Lisa's features just right (look at how natural her hands are) and his knowledge of geology in painting the mountainous background. Aside from Mona Lisa, da Vinci painted The Last Supper (the world's second most famous religious work, after the Sistine Chapel) and drew Virtruvian Man (the world's most famous drawing).

(2) Mona Lisa is a painting of Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a Florentine businessman called Francesco del Giocondo. Da Vinci's dad, a respected lawyer, suggested to his buddy, Francesco, that da Vinci might paint Francesco's wife. 'Mona' in Italian is a polite form of address, similar in English to saying 'Madam'. So the painting's title really means 'Madam Lisa'.

(3) Da Vinci started work on Mona Lisa in 1503, when Lisa was 24 years old. He worked on it constantly for the next four years. But the painting was so important to da Vinci that he carried it around with him, as he travelled Italy and beyond working on commissions. He kept tinkering it with it until his death in 1519 (and so Giocondo never got the portrait he had commissioned). Da Vinci once said:

"Art is never finished, only abandoned."

(4) The Mona Lisa is a really small painting, measuring just 30 x 21 inches (77 x 53 centimetres). But it packs a punch. The eyes of the Mona Lisa appear to follow you around the room. This is a trick of optics, pulled off when da Vinci painted one of Mona Lisa's eyes slightly off-centre. There is also a lot of mystery about the work: why, for example, is Lisa smiling? And why did da Vinci include behind his subject a background of winding paths leading to icy mountains?

(5) The Mona Lisa wasn't very famous until 21 August 1911. Until then, it was simply regarded as a fine example of Renaissance portraiture. But the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre in the summer of 1911. Security was lax (the museum didn't notice it was missing for 24 hours) and the police investigation was incompetent (bizarrely, Pablo Picasso was arrested on suspicion of the theft!). It turned out that the thief was a Louvre security guard, an Italian named Vincenzo Peruggia, who wanted to see the painting returned to Italy. He was caught when he tried to sell the work to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. In the meantime, the Mona Lisa had become front-page news around the globe.

Interesting fact...

June 2022 saw a bizarre attack on the Mona Lisa: a man disguised as an old woman in a wheelchair tried to smash the Mona Lisa's protective glass with his fists, smeared cream from a cake over the glass, and then threw rose petals at the painting. This is the latest in a line of attacks. Bullet proof glass was installed in the 1950s after an acid attack, and a woman hurled a ceramic mug at the painting in 2009!

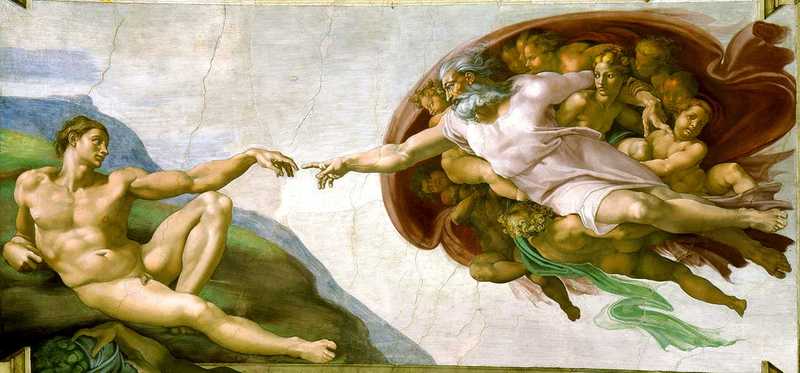

2. Michelangelo - The Sistine Chapel - 1508-1512

Michelangelo's frescos on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel are probably the greatest artistic achievement of western civilisation.

Top 5 facts

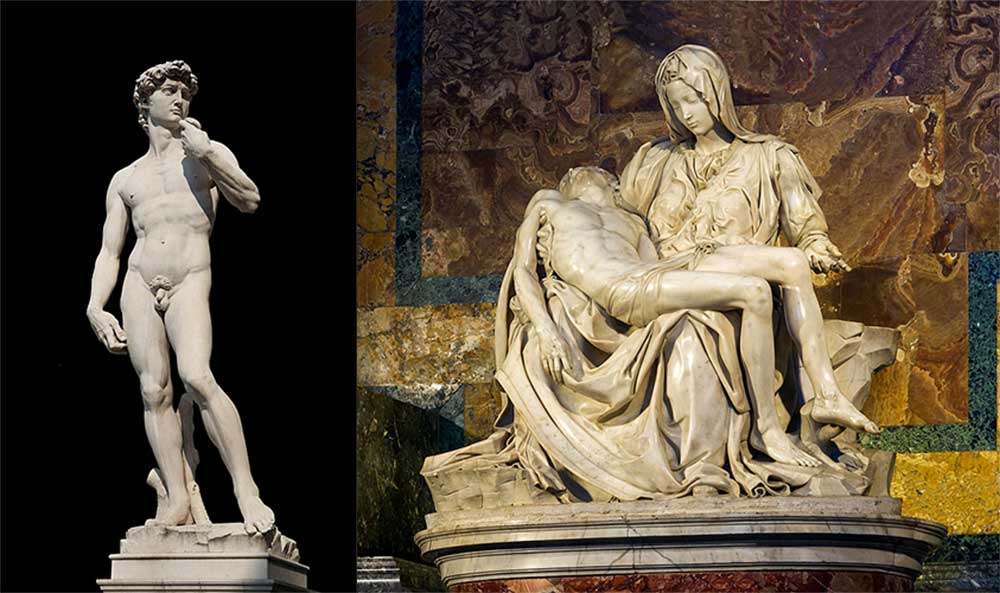

(1) Michelangelo (1475-1564) was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect and poet who was often referred to as 'Il Divino' (the Devine One) during his lifetime. He lived to the age of 88 and, in addition to his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, is most famous for his 17-foot sculpture of the biblical figure David (now housed in the Accademia Gallery in Florence) and the Peita (the Piety, a sculpture of Mary holding Jesus after the crucifixion, found in the Vatican).

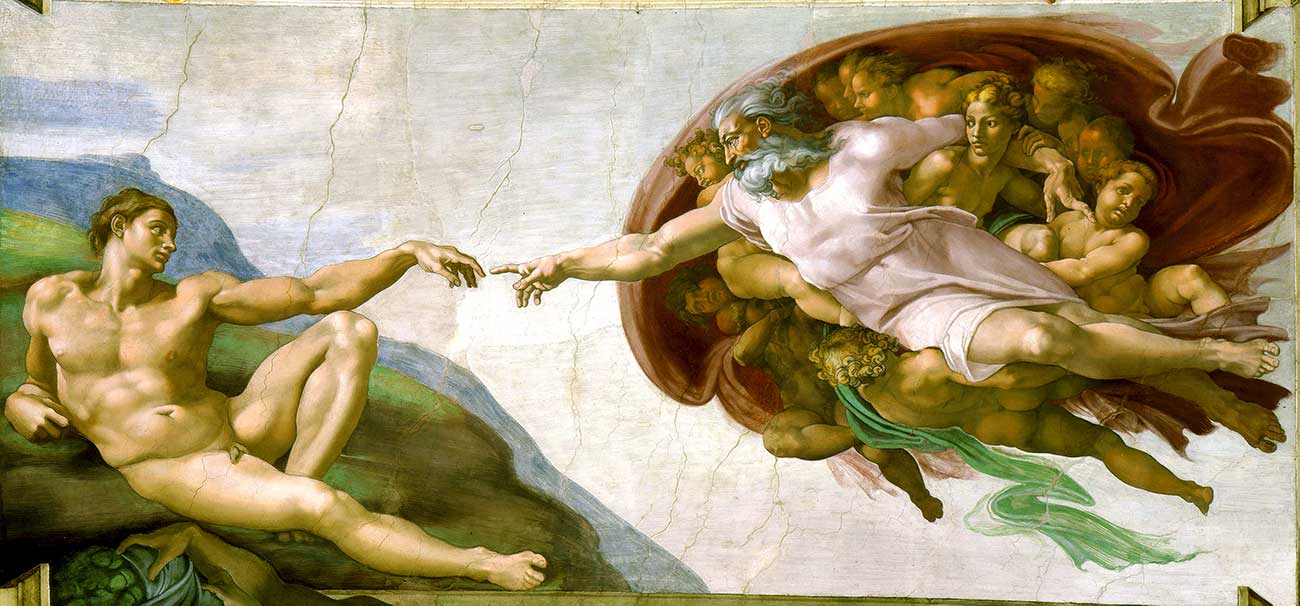

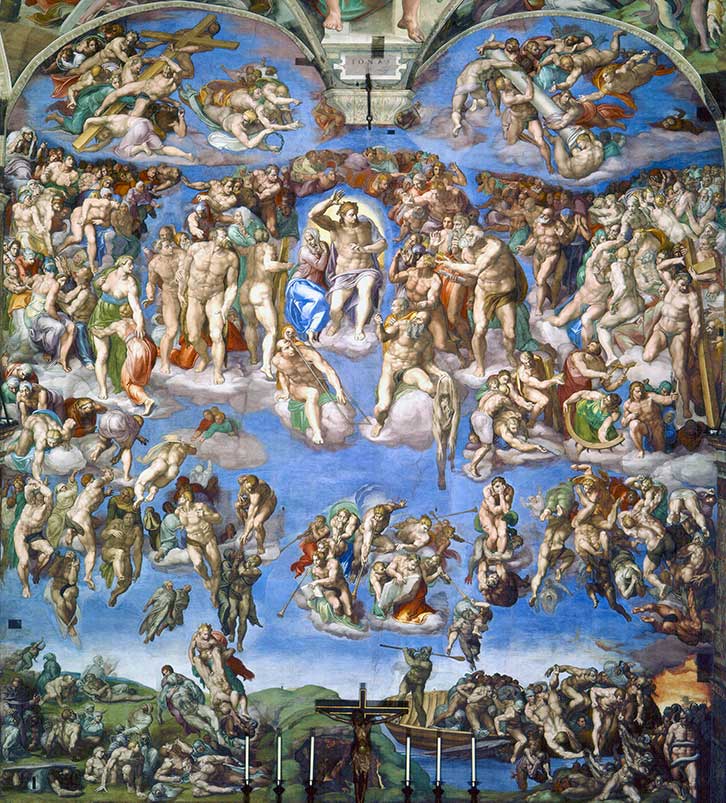

(2) Michelangelo’s paintings in the Sistine Chapel are frescoes, i.e. murals painted in freshly laid lime plaster (the word ‘fresco’ means ‘fresh’). There are two key works: the nine scenes from the Book of Genesis found at the centre of the chapel’s ceiling; and The Last Judgment, found on the sanctuary wall. Both works are enormous: the Sistine Chapel measures 40.9 metres (length) by 14 metres (width) by 13.4 metres (height). The ceiling was painted between 1508-1512 under Pope Julius II and the Last Judgment was painted much later, between 1536 to 1541, under Pope Paul III.

(3) The most famous part of the ceiling is the Creation of Adam, showing God (a man sporting a white beard) reaching out to touch a naked Adam’s left index finger. Eve looks on from beneath God’s sheltering arm. Found towards the centre of the ceiling, this scene alone is 9 feet high by 18 feet wide. It is one of the most reproduced scenes in the whole of art. The Last Judgment was painted 25 years later, with Michelangelo 67 years old when it was finished. Depicting the second coming of Christ, and God's final judgment on humanity, this is a jaw-dropping work of about 300 mainly nude (and often very muscly!) figures.

(4) Painting such enormous amounts of space using freshly mixed lime was difficult. The lime had to be mixed each morning, and in the early days the lime was too wet, meaning that it became mouldy and had to be removed. Michelangelo had to work quickly and accurately from preparatory drawings to make progress before the lime dried. And he worked from a height of about 12 metres, standing on make-shift scaffolding that he designed himself. As Goethe said in 1787:

"Until you have seen the Sistine Chapel, you can have no adequate conception of what man is capable of accomplishing."

(5) The Sistine Chapel was built by Pope Sixtus IV between 1473 and 1481. Aside from Michelangelo’s frescoes, it is best known for being the home of the papal conclave: the meeting of cardinals held after the Pope’s death to choose his successor. The conclave has some unusual features: cardinals are locked in the Sistine Chapel until a successor Pope is chosen (a process that often takes several days), and ballot papers are burned with chemicals to give off either black or white smoke (black smoke signifying an inconclusive vote; white smoke to show that a successor has been chosen).

Learn more by listening to the BBC's In Our Time podcast on the Sistine Chapel.

3. Rembrandt - The Night Watch - 1642

Rembrandt's The Night Watch is the jewel in the crown of Amsterdam's Rikjsmuseum.

Top 5 Facts

(1) Rembrandt van Rijn, usually just known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch painter who lived from 1606-1669. He came from a humble background, was apprenticed at the age of 14, and is the best-known painter of the Dutch Golden Age (ahead of Johannes Vermeer and Frans Hals). After the Night Watch, Rembrandt’s next most famous paintings are his 80+ self-portraits and The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1632).

(2) The Night Watch, or to give it its full name Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, is a group portrait of a militia company featuring 21 people. At the centre are the company's commander and his diminutive deputy, with a reclining female holding a dead chicken (of all things) to their immediate left. The rest of the work is a riotous affair: rifles are being cleaned, recharged and aimed at the enemy (one has even gone off accidentally!); pikes are pointed in all directions; a military standard is being waved; a dog is barking; and a drummer is beating away. This is an almost comic painting completely unlike the more conservative works of militiamen that had come before - and Rembrandt must have been nervous about how it would be received.

(3) The Night Watch is massive, measuring 363 x 437 centimetres. In fact, Rembrandt’s original canvass was even larger, with significant sections on the left and to the top of the work having been cut off in 1725 when the painting was moved to a new home. The canvas’ size has led to debate about where it painted: it was too big to fit in Rembrandt’s (large and opulent) Amsterdam townhouse. When it was finished in 1642, it was taken to the headquarters of the Civic Militia (who by then had a largely symbolic "dad's army" role) – fulfilling a commission they had made two years earlier.

(4) Rembrandt was a spendthrift. Not only did he spend 13,000 Gilders on his townhouse in a fashionable district of Amsterdam, but he filled it with all sorts of eclectic objects including suits of armour, bows and arrows, pottery, seashells, stuffed animals and sculptures. Things eventually caught up with Rembrandt: artistic tastes changed (but Rembrandt refused to change his style), he was declared bankrupt in 1656, and he died penniless 13 years later and was buried in a pauper's grave.

(5) The Night Watch was attacked by vandals three times in the 20th century. An unemployed cobbler, protesting his inability to find work, attempted to slash it with a shoe knife in 1911 (it was protected by a thick layer of varnish). The painting was subjected to another attack in 1975, this time by an unemployed schoolteacher, resulting in a 30-centimetre slash (a four-year restoration effort was largely successful). Most recently, the painting was sprayed with acid by an escaped psychiatric patient in April 1990; water was quickly splashed on the canvas, preventing any damage. These days, the painting is housed in a large glass box as part of a complex restoration effort.

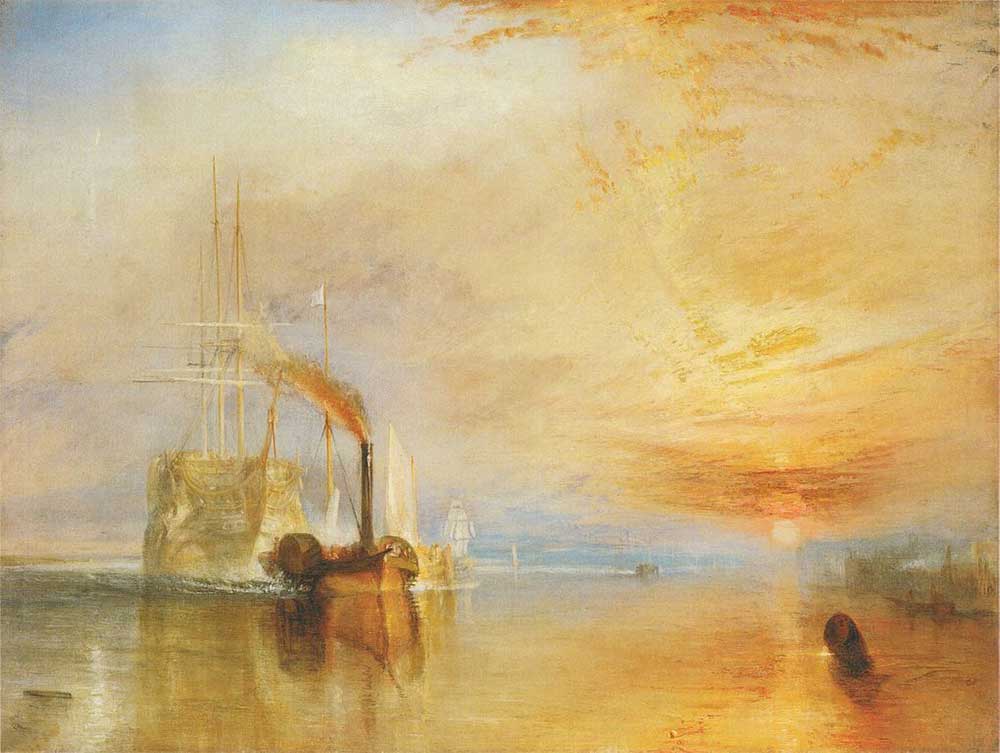

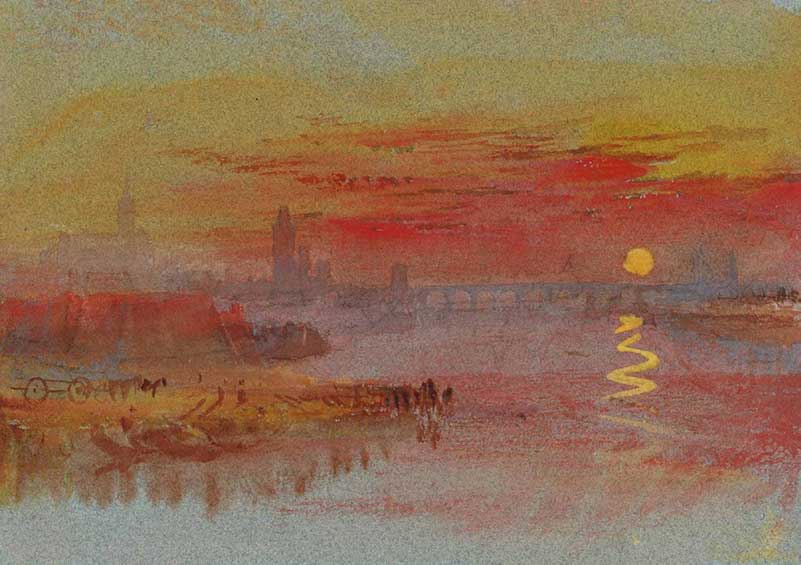

4. JMW Turner - The Fighting Temeraire - 1838

The Fighting Temeraire is regularly named the UK's favourite painting.

Top 5 Facts

(1) JMW Turner was born into humble circumstances in 1775. His dad was a barber and his mother was descended from a family of butchers and ended up in an asylum. Turner was immensely talented and hugely ambitious, painting wilder, brighter and more expressive art than his contemporaries like Constable and Stubbs. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy at the age of 15 and was elected an Academician at the youngest ever age of 26. Turner’s other famous works include Rain, Steam and Speed (1844) and Northern Castle, Sunrise (1845). He became increasingly eccentric in the years before his death at the age of 76.

(2) The Fighting Temeraire was produced by Turner in 1838, at the height of his powers. It depicts HMS Temeraire being towed up the Thames by a new paddle-wheel steam-tug, en route to a breaker’s yard at Rotherhithe in south-east London. The last voyage of the magnificent vessel is crowned by a glorious sunset occupying the right-hand half of the painting, with the moon only just visible on the left. The right-hand bank of the River Thames can be seen on a careful inspection of the painting, with barely any other traffic visible on the river’s placid waters.

(3) The Temeraire was a three-masted battleship equipped with 98 cannons. It played a starring role at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar between Britain and France. Lord Horatio Nelson, the admiral of the British fleet, launched an audacious full-frontal attack on the French. When Nelson’s flagship, HMS Trafalgar, got into difficulties and was about to be boarded the Temeraire came to the rescue. It went on to capture two French ships during the battle and was the only ship mentioned in dispatches.

(4) Turner’s painting does not seek to provide a photographic representation of the scene. For example: the River Thames would have been far more crowded with ships than Turner suggests; the sun would have been setting in front of and not behind the Termeraire; and the funnel of the tug-boat is in the wrong place. But to carp about these things is to miss the point. Turner was putting together a composition to mark the end of the golden era of sail power.

(5) The Fighting Temeraire was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1839, to wild acclaim. One critic, known for his facetious reviews, abandoned his usual tone and wrote that Turner’s work was “as grand a picture as ever figured on the walls of any academy, or came from the easel of any painter.” Turner left the painting to the nation on his death in 1851, and it is now found in London’s National Gallery. The Temeraire was voted Britain’s favourite painting in a 2005 poll, and features on the 2020 version of the UK’s £20 note.

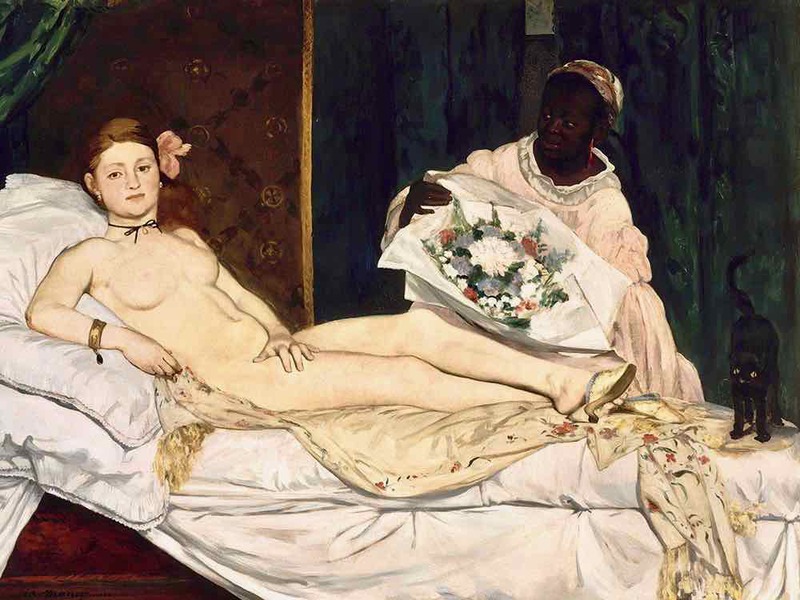

5. Edouard Manet - Olympia - 1863-4

Edouard Manet's Olympia is often described as the first true work of modern art.

5 Key Facts

(1) Edouard Manet was born in Paris in 1832 into a life of luxury: his father was a high-ranking civil servant and his mother the goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince. Manet initially quarrelled with his father about his career choice (Dad wanted him to be a lawyer!). But Manet Snr eventually gave in and Manet went to study in a famous Paris studio. The Manet’s family money was critical to Manet’s success: he did not have to sell paintings to make ends meet and so could paint what he wanted. Manet spent his life taking on the conservative art establishment, which expected paintings to be of religious, mythological or historical scenes. He was mainly a portraitist who captured his subjects using bright paints and broad-brush strokes, in thoroughly modern settings. Manet’s other famous works include Dejeuner sur l’Herbe (1862-3) and Bar at the Folies Bergeres (1882).

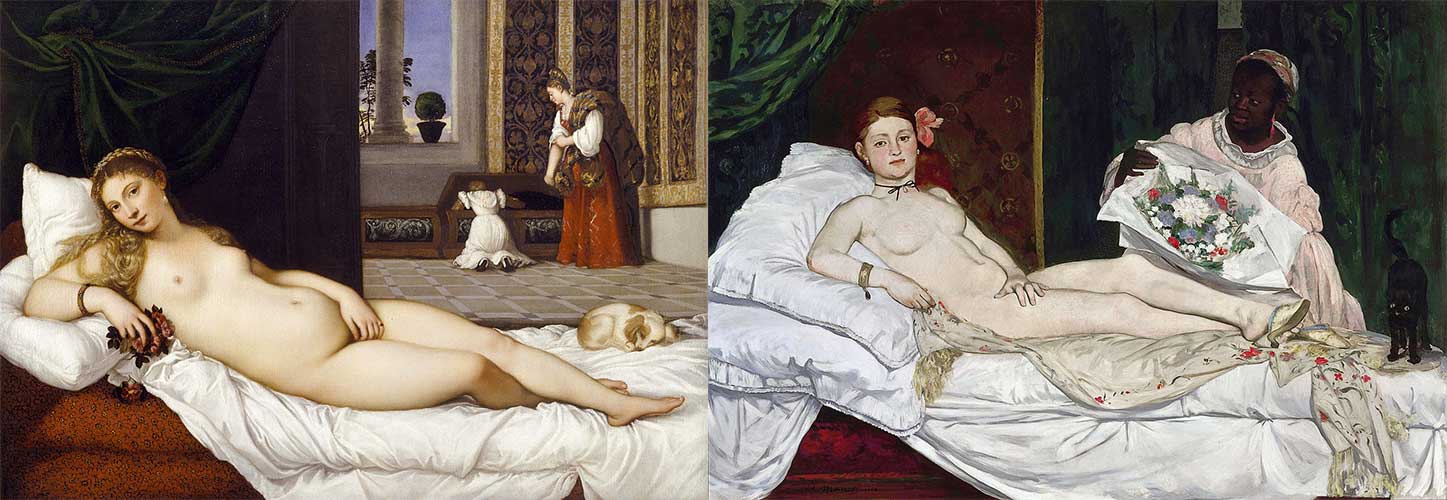

(2) Manet painted Olympia in 1863, towards the start of his career. He based the composition on Titian’s Venus of Urbino. But whereas Titian’s painting symbolised virtues such as faithfulness and motherhood (see the child looking for a toy at the back of the painting), Manet’s work depicted a prostitute. Although Manet never accepted that Olympia was a courtesan, his composition leaves no room for doubt: the black cat with raised tail, the orchid in the hair and the black ribbon around Olympia’s neck were all symbols of prostitution. And then there is Olympia’s maid, carrying a bunch of flowers wrapped in cheap newspaper, from a satisfied client.

(3) The most remarkable thing about the painting is the defiant stare on Olympia’s face: she is not going to apologise to anyone about her way of making a living. This made the work deeply unsettling for Parisians, many of whom visited prostitutes on a regular basis.

(4) Olympia was displayed at The Salon, an annual exhibition held in Paris each year, in 1865. It caused uproar: the public were so affronted by the work that many sought to physically attack it with canes and umbrellas – the painting eventually had to be moved for its own protection! And the art critics were remarkably harsh, referring to Olympia as (amongst other things) a “female gorilla”, a “yellow-bellied odalisque” and a work of “perfect ugliness”.

(5) Manet did not sell Olympia during his lifetime. In 1890, seven years after Manet’s death, Claude Monet organised a collection to purchase Olympia from Manet’s widow for the French state. He raised 20,000 francs and the painting was duly bought. But the still-conservative art establishment refused to hang the painting in The Louvre for a further 17 years.

Learn more on our Olympia: In-Depth page.

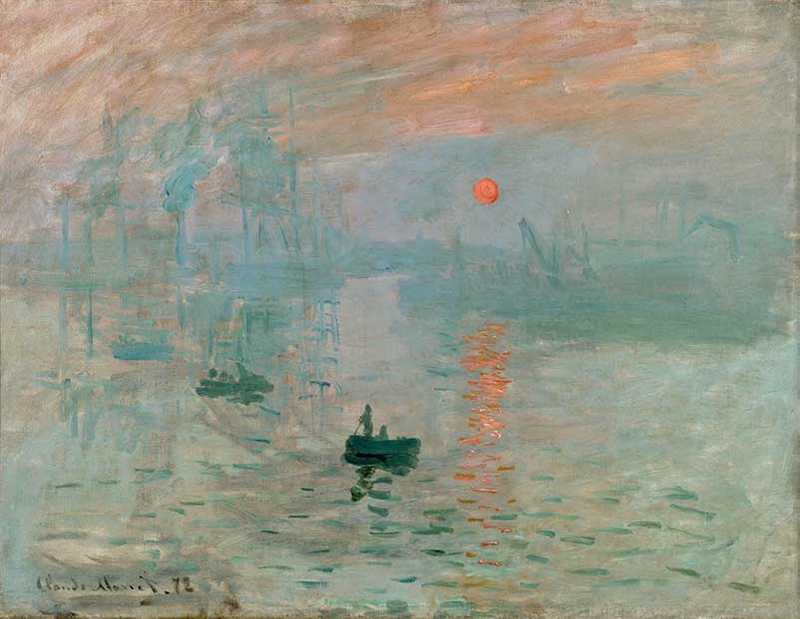

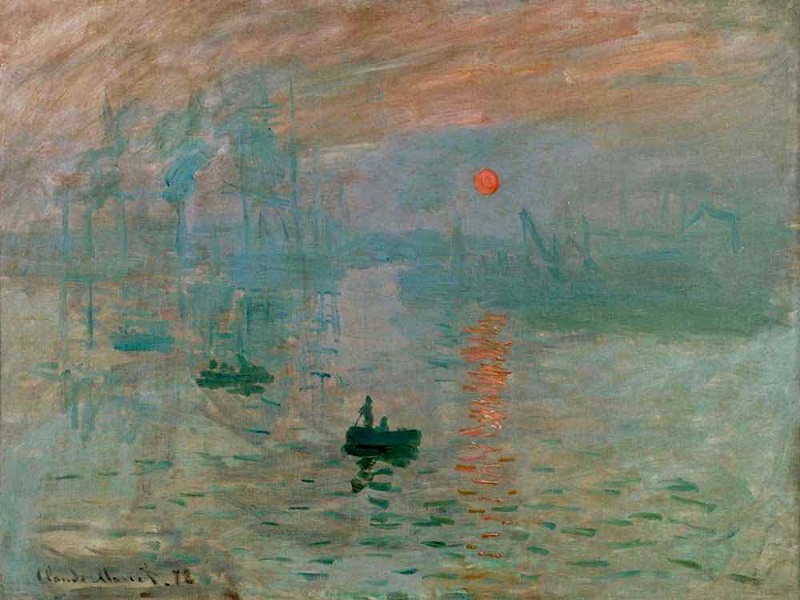

6. Claude Monet - Impression: Sunrise - 1872

Impression: Sunrise is the painting that got the Impressionists their name.

Top 5 Facts

(1) Claude Monet was born in Paris in 1840, the second son of a shopkeeper. His artistic flare was obvious from a young age, with Monet drawing caricatures of local celebrities and selling them for 10 or 20 francs (good money back in the 1850s!). Monet came to Paris in 1859 and attended Suisse’s and then Gleyre’s studios to hone his skills. He had some successes, and plenty of failures, in the 1860s, with the conservative art establishment often barring his entries from the premier art event of the year, an exhibition called The Salon. By 1874, Monet had had enough: he, Degas and Renoir organised what was to be the first of eight independent impressionist exhibitions. The public reaction was almost entirely negative, as we explain below. But Monet slowly gained acceptance, renown and riches during the 1880s and 1890s, painting multiple works on subjects including poplars, wheat stacks, Rouen Cathedral, the Houses of Parliament and water lilies. Today he is the most famous impressionist.

(2) Monet painted Impression: Sunrise on 13 November 1872 from his hotel room overlooking the harbour of Le Havre on France’s northern coast. He probably painted the canvas in a single sitting, racing against the rising sun. The eye is drawn to the burnt-red sun and the reflection it casts over the water (inspired by JMW Turner's Scarlet Sunset). The next key image is a central rowing boat, with an oarsman and a single passenger. Closer inspection reveals two further rowing boats, the masts of anchored clipper ships, factory chimneys spewing out smoke, and cranes.

(3) Monet did not actually name the painting Impression: Sunrise. In the rush to get the first impressionist exhibition organised, Monet delivered a stack of canvasses to Renoir’s brother, Edmond. When Edmond asked Monet what to call it, he replied ‘impression’ – with Edmond adding the ‘Sunrise’ to make the name more distinctive.

(4) The painting was panned by the critics, with reviews saying that it was “hostile to good artistic manner” and that the public “burst out laughing” when they saw what the impressionists had produced. More positively, the critic Louis Leroy accidentally helped coin the term ‘impressionist’, intended as an insult, when he wrote an article entitled “Exhibition of the Impressionists at the Boulevard des Capucines”. But the article said this of Impression: Sunrise

“Impression! Of course. There must be an impression somewhere in it. What freedom ... what flexibility of style. Wallpaper in early stages is more finished than that.”

(5) When Impression: Sunrise was first sold in 1874, it fetched a mere 800 francs. Its next sale, some three years later, was even worse: it went for 210 francs. Happily the purchaser (Dr George de Bellio) left the painting to his daughter, who in turn left it to Paris’ Musee Marmottan Monet in 1940. Fast forward 45 years, and Impression: Sunrise was stolen from the Marmottan in an audacious gunpoint robbery. It was missing for five years before being traced to a Corsican villa and recovered. Fortunately, the canvas did not sustain any serious damage.

Learn more on our Impression: Sunrise page.

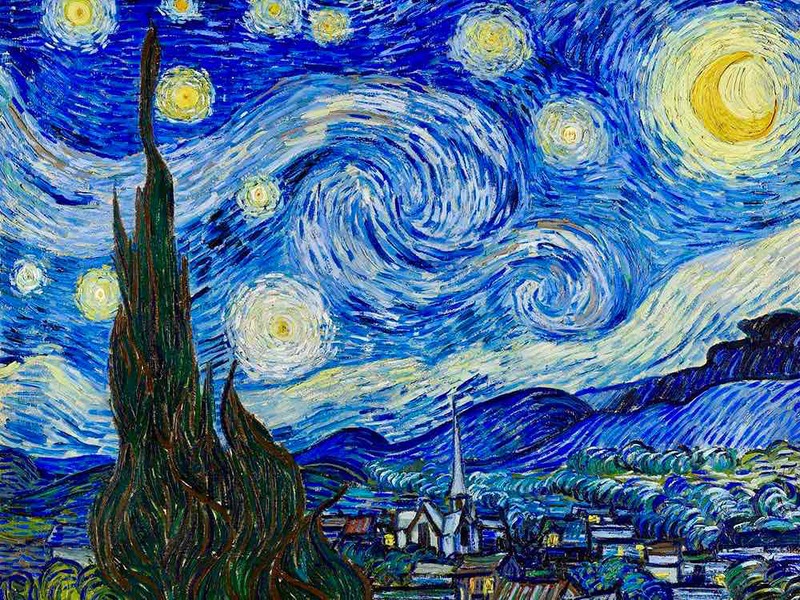

7. Vincent van Gogh - Starry Night - 1890

Overlooked during van Gogh's lifetime, Starry Night is now one of the world's most iconic paintings.

Top 5 Facts

(1) Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) is the classic example of an artist who struggled for his vocation. Born to conservative parents in Holland, van Gogh made his way around Europe in his twenties searching for his calling – he tried his hand as a gallery assistant, a teacher and a missionary and left a trail of disappointed employers and failed relationships in his wake. Van Gogh turned to art full-time in the early 1880s and initially painted in the earthy tones of the Dutch style, producing his first masterpiece – The Potato Eaters – in 1885. The next year, van Gogh moved to Paris to live with his brother Theo, and was exposed to the impressionists (in particular Pissarro and Degas). This resulted in a radical change in his artistic style: he first started to use brighter colours and then, from 1887 until his death in 1890, produced post-impressionist works that did not merely seek to capture what van Gogh saw but also his emotions about the scene he was painting. Van Gogh’s other famous works include The Sunflowers, his Self-Portraits, Café Terrace at Night, the Bedroom, Wheatfield with Cypresses and Irises.

(2) Starry Night was painted in June 1889, when van Gogh was in a psychiatric hospital in Saint-Remy in south France. Van Gogh checked himself into the hospital, with Theo’s assistance, after he infamously cut off his left ear with a razor blade following a furious argument with fellow painter Paul Gauguin in December 1888. (For those that don’t know the story: van Gogh then delivered the bloody flesh to a local brothel in the town of Arles, where he was living with Gauguin, and passed out from the blood loss.) Van Gogh was to stay at the Saint Remy asylum until May 1890, the month before he committed suicide. He could see the scene of the Starry Night from his window, and painted it during the daytime from the asylum’s ground floor.

(3) Van Gogh loved the night sky, observing that “the sight of stars always makes me dream”. His composition is dominated by a luminous moon and eleven stars, which many say is a reference to Genesis 37:9 (“… behold the … moon and the eleven stars”). In the foreground is a large cypress tree swaying in the breeze. The composition is completed with rolling hills and a small village, complete with a church with an impressive steeple. But van Gogh was not particularly satisfied with the work: he didn’t want to waste money on sending it to Theo (who was an art dealer in Paris) because he didn’t think it would sell; and he referred to it as a “failure” in a letter sent to an artist friend, in part because the stars were “too big”.

(4) Starry Night, as with all but one of van Gogh’s works, remained unsold at the time of his death at the age of 37. The task of popularising the painter fell to Theo’s widow, Jo van Gogh-Bonger (Theo himself died shortly after Vincent). Jo carefully curated Vincent’s paintings, which were left to her on Theo’s death, and also organised and translated Vincent’s many letters to Theo. She held exhibitions of van Gogh’s works, culminating in a 484-painting exhibition in Amsterdam in 1905. But, whilst the reviews were generally positive, Starry Night itself was slammed. One critic likened the stars to fried dough balls eaten in Holland on New Year’s Eve.

(5) Starry Night was bequeathed to New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1941 (an earlier work, Starry Night over the Rhone, is found in Paris' Musee D'Orsay). Since then, Starry Night's fame has skyrocketed and it is now one of the most recognisable works in western art. Don McLean famously wrote about Starry Night in his 1971 song entitled Vincent; its opening words are these:

“Starry, starry night Paint your palette blue and grey Look out on a summer’s day With eyes that know the darkness in my soul.”

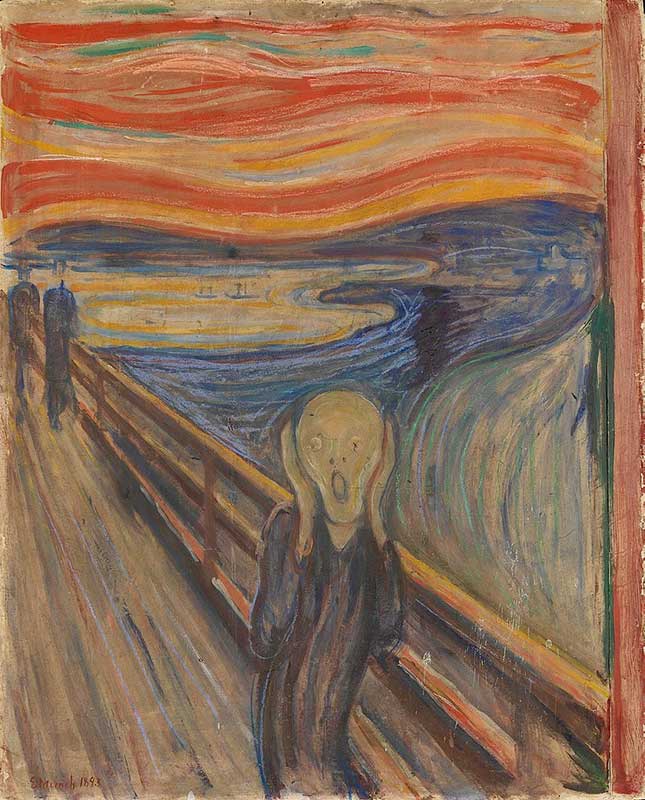

8. Edvard Munch - The Scream - 1893

Edvard Munch's The Scream is probably the most haunting painting ever produced.

Top 5 Facts

(1) Edvard Munch was born in a small Norwegian village in 1863. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was five, as did his favourite sister when he was 13. Munch’s father was nervous and highly religious, with Munch later commenting that “the angels of fear, sorrow, and death stood by my side since the day I was born”. Munch was determined to become an artist from his teenage years, despite his father’s view that it was an “unholy trade”. And, given his upbringing, it is easy to see how Munch was drawn to introspective, expressive, and even perturbing subjects. Aside from The Scream, Munch’s other key works are Madonna (a bare-breasted, half-length female figure) and The Sick Child. Munch died in Oslo in January 1944, aged 80.

(2) Munch painted The Scream in 1893. The central figure – it is unclear whether it is a man or a woman – is open-mouthed and covering his/her ears. It is also unclear whether the figure is screaming or trying to block out the scream of another (Munch was later to describe the “infinite scream passing through nature” - suggesting the latter). Two figures are seen in the background on a wooden walkway, with the blood-red sky being the composition’s other striking feature. Overall, the work symbolises the anxieties, uncertainties and paradoxes of human existence. It is often described as disturbing and haunting.

(3) Munch made various versions of The Scream: two are painted, two are in pastel, and he made several prints from a lithograph stone. Unusually and somewhat bizarrely, the oil versions of The Scream are not painted on wood or canvas but on cardboard. This was, in fact, part of Munch's artistic process - he saw his paintings as living things and wanted them to have their own lives, sometimes even leaving them outside in the rain. When asked about this, Munch said:

"It does them good to fend for themselves."

(4) Thieves have frequently targeted The Scream. In February 1994, on the opening day of the 1994 Winter Olympics (being held in Lillehammer, Norway), two men stole the painting from Oslo’s National Gallery (the painting had been moved to a temporary location to accommodate Olympic celebrations). The thieves left a note reading “Thanks for the poor security”! The painting was recovered shortly afterwards, following a British/Norwegian sting operation. A decade later, a different version of The Scream and Munch’s Madonna were stolen from Oslo’s Munch Museum. Both paintings were recovered in 2006, but had sustained damage and required extensive restoration.

(5) One of the two pastel versions of The Scream was sold by Sotheby’s in London in 2012 for a then pastel world-record $120 million. The auction saw a 12-minute to-and-fro bidding war. The successful buyer was later identified as the American businessman Leon Black. This version of The Scream is now the 22nd most expensive painting ever sold.

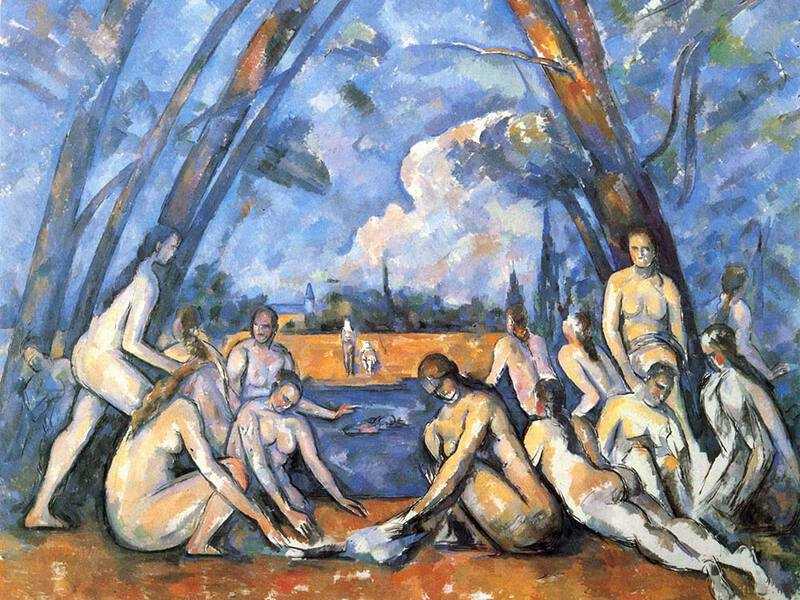

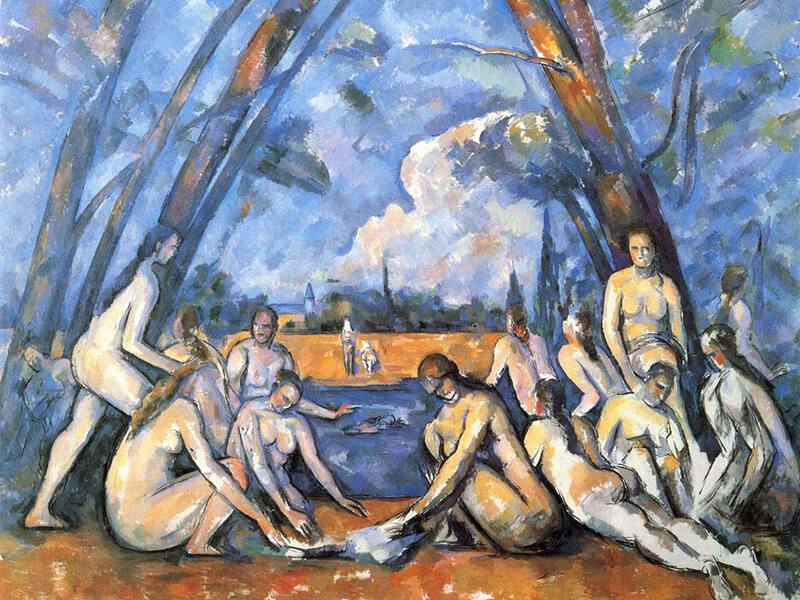

9. Paul Cezanne - Large Bathers - 1898-1905

Cezanne's Large Bathers, this artist's final and most important work, is a key bridge between impressionism and expressionism/cubism.

Top 5 Facts

(1) Paul Cezanne was born in 1839 in Aix-en-Provence, studying there before coming to Paris in the early 1860s. Cezanne’s early works, from his so-called ‘dark period’, were often violent (they had names like ‘The Murder’ and ‘The Abduction’). But Cezanne was persuaded by Camille Pissarro to embrace the impressionist style, and he joined the first and third impressionist exhibitions in the 1870s – though the critics gave him a hard time. Cezanne came into his own when he returned to the south of France in 1880, producing a series of paintings of nude men and women (see further below), Mont Saint-Victoire, the Provencal countryside/coastline, Provencal produce, and farmhands playing cards (Cezanne’s Card Players is the most expensive impressionist work ever sold). Cezanne struggled with relationships throughout his personal life, becoming estranged from both his wife, Hortense, and best friend, Emile Zola. He died in 1906 after catching pneumonia when caught in a storm whilst out painting.

(2) Cezanne painted over 200 versions of male and female bathers between the early 1870s and his death in 1906. He was too shy to hire models to pose for him when painting his bathers, so he relied on memories of academic paintings that he had studied in his youth. There was another reason Cezanne didn’t hire models: he was a perfectionist and they often complained when he made them sit in the same position for hours on end, and return for sitting after sitting, so he could get things just right.

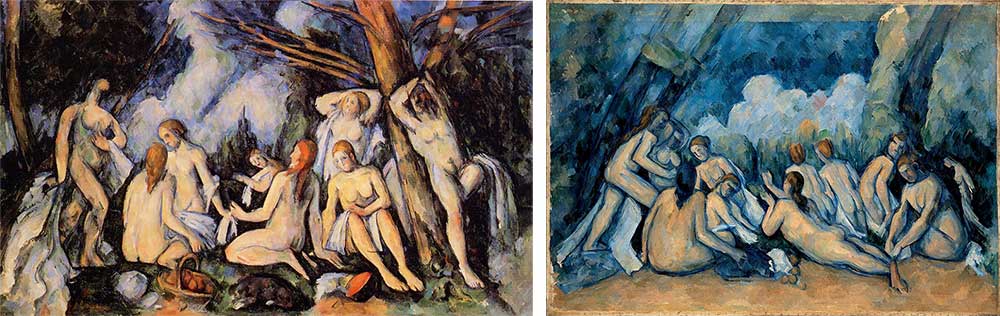

(3) Amongst the various bathers, three large paintings stand out for special mention. They are known as the Large Bathers, or Les Grandes Baigneuses. The largest and most significant, pictured above, is a 210 x 250-centimetre canvas held by the Philadelphia Museum of Art depicting 15 women in total, mainly lounging or playing in front of a river (one is swimming). In the background there is a male figure, probably Cezanne, with a dog watching from afar. The painting is given geometrical structure by leaning trees forming a triangle. The other key versions of the Large Bathers are held by London’s National Gallery (127 x 196 centimetres) and the Barnes Foundation in Pennsylvania (132 x 219 centimetres).

(4) Cezanne worked on two of The Large Bathers for years and never finished any of them to his satisfaction. The Barnes Foundation’s version was started first, in 1895. We know that Cezanne worked and re-worked this painting because a 1904 photograph is very different from the final version, and because of the large quantity of paint on the canvas. The National Gallery’s version came next, started in 1898. The final and most important Philadelphia version was probably only started in Cezanne’s last months.

(5) The Large Bathers influenced the development of 20th century art in a variety of ways. For one thing, Cezane uses geometry in his composition, something later embraced by Picasso and Matisse. Secondly, he intentionally distorts the bodies of some of his bathers; for example, the woman on the far left of the Barnes Foundation’s version has a tiny head. This again is a trait of post-impressionist works. The impact of Cezanne’s work was felt quickly: Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, painted in 1907, features a group of women with distorted bodies and heads; Matisse acquired one of Cezanne’s early bathers in 1899; and English artist Henry Moore (1898-1986) said that seeing The Large Bathers for the first time was the most significant moment in his artistic career. Indeed, both Picasso and Matisse are reputed to have said that Cezanne was:

"The father of us all."

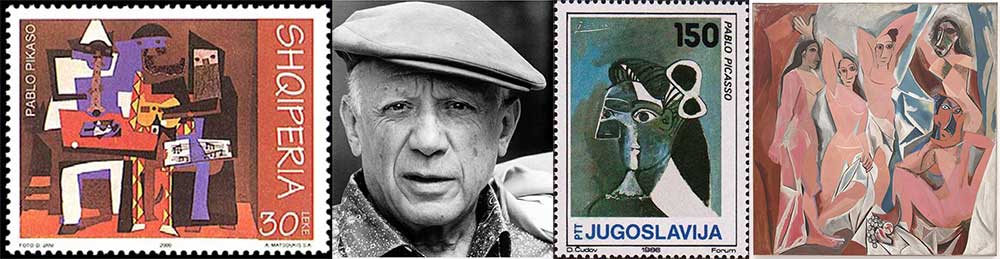

10. Pablo Picasso - Guernica - 1937

Picasso's Guernica is the world's most important anti-war artwork.

Top 5 Facts

(1) Pablo Picasso was born in Malaga, Spain in 1881, though he went on to spend most of his adult life in France. He was an artistic polymath: painter (and co-founder, along with Georges Braque, of the cubist movement), sculptor, printmaker, potter and theatre designer were amongst his many talents. Picasso is the best-known artist of the 20th century, and was fortunate enough to enjoy the spoils of his success during his own lifetime. After Guernica, Picasso’s next most famous works are Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1807) and the Weeping Woman (1937). Picasso died in Mougins, France, in 1973.

(2) The Spanish Civil War lasted from July 1936 to April 1939, pitting nationalists (led by General Franco) against the legitimate republican government. The war turned decisively in Franco’s favour once he started receiving military support from Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. Picasso’s Guernica is a cubist/surrealist painting designed to memorialise the carpet-bombing of the eponymous market town by German and Italian planes on 26 April 1937. The bombing was one of many atrocities committed by the nationalists during the war: it took place in mid-afternoon on market day, with its c. 1000 victims mainly women and children; and it was covered up by the nationalists, who outrageously accused the republicans of bombing their own town. The bombing was covered in The Times the next day, with an eye-witness article written by George Steer on its front page – it was this article that inspired Picasso to paint the work.

(3) Picasso’s Guernica is a huge canvas, measuring 349 x 776 centimetres, painted in black/white/grey and in cubist/surrealist style. Picasso produced the work in just three weeks. The work is haunting. Working from left to right, the viewer sees: a woman clutching her dead child and screaming to the heavens; a dead solider; a bull (perhaps representing Picasso) surveying the scene; a horse which has been gored with a lance; a woman trying to escape from a building, and another holding an oil lamp (perhaps signifying hope). Picasso refused to comment on the meaning of his painting during his life, observing that:

“This bull is a bull and this horse is a horse.”

(4) The republicans had approached Picasso to paint a mural earlier in 1937. Picasso was living in Paris at the time, and had not been to Spain since 1934 (he would never return). He started work immediately after learning about the bombing and, when he had a first version of the canvas, experimented by pinning a red teardrop and coloured wallpaper to it – he decided these effects did not work, leaving Guernica as the world’s most recognisable monochromatic work.

Interesting fact...

Picasso was living in Paris during the Second World War. Legend has it that a gestapo officer visited his home and saw a photograph of Guernica. He asked "did you do that", to which Picasso retorted "no, you did."

(5) Guernica is now housed in Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofia. Picasso refused to allow the work onto Spanish soil during the nationalist government’s reign, and so it was displayed in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art until 1981. The work was vandalised by a Vietnam war protestor in 1974, but quickly repaired. A full-sized tapestry of Guernica was hung in the entrance to the UN’s Security Council room in New York from 1985 until February 2021 and a mosaic of the work stands in Guernica's main square.

11. Numbers 11-20

Coming up with our list of the Top 10 Paintings Ever was difficult. Here are another 10 masterpieces that almost made the cut.

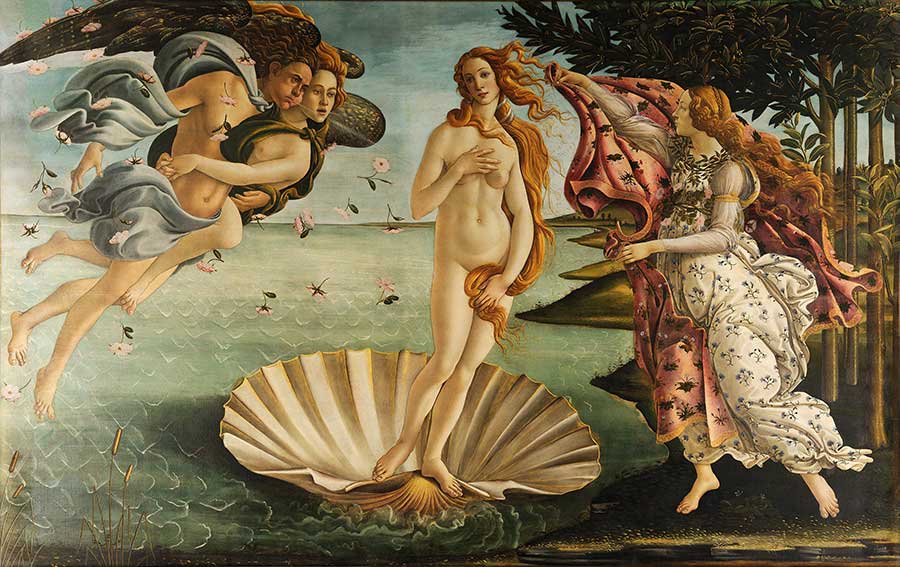

The Birth of Venus – Botticelli – 1486

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) was an Italian painter of the early Renaissance. His most famous work, The Birth of Venus, depicts the goddess Venus emerging from the sea fully grown (an important scene from Greek mythology). Venus is standing on a giant scallop shell, the island that she is being blown towards by Zephyr is Cyprus, and she is about to be wrapped in a gown decorated with spring flowers. One of the iconic works of the Italian Renaissance, this enormous painting (172.5 x 278.9 cms) was commissioned by the powerful Medici banking family. It was hugely controversial at the time, Botticelli depicting a female nude who was not ashamed of her sexuality. These days, the Birth of Venus is found in the Uffizi gallery in Florence.

Girl with a Pearl Earring – Johannes Vermeer – 1665

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) was one of the leading painters of the Dutch Golden Age. He painted Girl with a Pearl Earring not as a portrait but as a tronie - an imagined person. The girl's look is hard to pin down: is it flirtation, apprehension or longing? We can't make our mind up (perhaps it is a mix of all three). What we do know is that the girl is wearing an oriental turban, that the pearl - painted with just two brushstrokes - is too large to be real, and that the painting was bought for the equivalent of $24 at the end of the 19th century! Not a bad deal for one of the world's iconic works, which was later donated to the Mauritshuis in the Hague.

The Third of May 1808 - Francisco Goya - 1814

Francisco Goya (1746-1828) was a Spanish romantic painter. He painted two works to remember Spanish resistance to Napoleon's army during the Peninsula War (which involved Napoleon's France pretending to be friends with the Spanish and then turning on Spain). Goya's works were called the Second and the Third of May 1808. The Second of May depicts a failed revolt by Spanish peasants, with the more famous Third of May showing the aftermath: Spanish peasants being executed by French soldiers. The work is important to the development of art: battle scenes were, before Goya's work, meant to depict glorious victories; in contrast, Goya produced a gory and moving scene showing man's ability to be inhuman. The effect was achieved through light and dark, the clever use of perspective, and the crucifixion pose of the painting's principal figure. Manet was later to draw inspiration from Goya's work for his Execution of Maximilian. Painted on a monumental scale (208 x 347 cms) the Third of May is now found in Madrid's Museo del Prado.

Liberty Leading the People – Eugene Delacroix – 1830

Eugene Delacroix (1798-1663) was the leader of the romantic art movement, which focused on colour, movement and emotion (over accuracy of representation and historical or mythological scenes, favoured by his main rival the neoclassicist Ingres). This enormous work - 260 x 325 cms - commemorates the July 1830 revolution, in which French King Charles X was toppled. The bare-breasted woman leading the charge holds a tricolour, stands atop a mound of fallen comrades, and leads people from all socio-economic classes (check out the guy wearing a top hat!). It was initially bought by the French state, but then housed in an attic when it was considered to be too controversial to be put on show. Liberty made her way to the The Louvre in Paris in 1874, where she is still to be found.

Whistler’s Mother – James Whistler – 1871

The US-born James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) led a peripatetic existence, moving from the US, to Russia, Paris and London. He painted his most famous work in Chelsea, London over the course of three months in 1871 (quick by Whistler's standards). It came about by chance: one of Whistler's models failed to turn up, and so his mum stepped in; early compositions showed her standing, but this ended up being too demanding and mum was allowed to take a seat. The work is an outstanding example of the artist's use of blacks and greys (its first name was Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1). Note the delicate features of mum's resigned face (she was in mourning following her husband's death). The painting was not an immediate success when it was initially shown at the Royal Academy, but shot to fame when it went on a US tour during the great depression. It is now found in the Louvre.

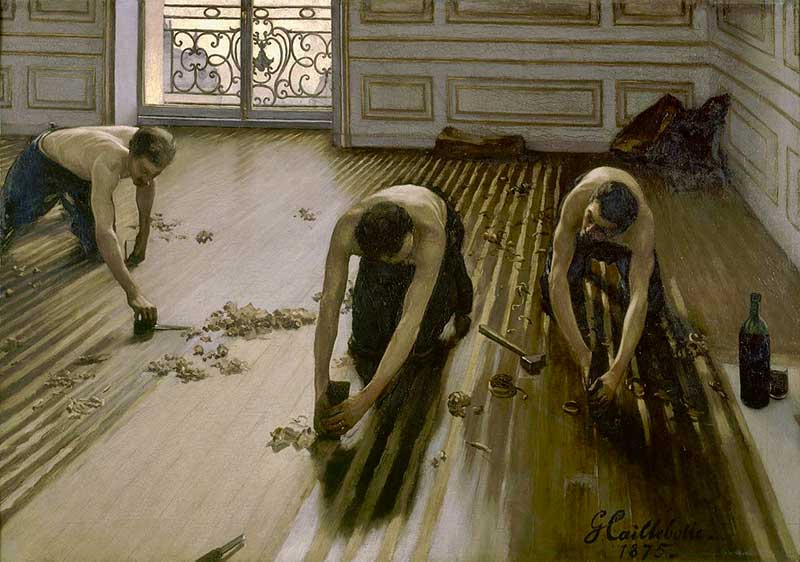

The Floor Scrapers – Gustave Caillebotte – 1875

Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894) was a French impressionist painter. He only took up painting in a serious way in the early 1870s, quickly forming strong bonds with the impressionist group (whose paintings he often purchased) and exhibiting in the 1876 second impressionist exhibition. In this painting Caillebotte shows urban labourers - an unusual choice of subject for the time - stripped to the waist and working hard. It was immensely controversial: one critic wrote that it made him "sick at heart". We love the composition and structure of this work, which is perhaps the least well known of all the paintings on this page. The Floor Scrapers is now found in the Musee d'Orsay in Paris.

Luncheon of the Boating Party – Pierre-Auguste Renoir – 1881

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1842-1919) was one of the original group of impressionists, alongside Monet, Degas, Manet and Pissarro. He was born in Limoges and initially worked in a porcelain factory painting cups and saucers. Renoir was brilliant at painting two things: women and joy. This painting merges those two skills with Renoir's inimitable luminous style. The scene is of a boating party having Sunday lunch at the Hotel Fournaise, where Renoir had courted his wife. There is no deep meaning here: the models are just having fun on their day off. As Renoir said:

"a picture has to be pleasant, delightful and pretty -- yes, pretty. There are enough unpleasant things in the world without us producing more."

A Sunday Afternoon – Georges Seurat – 1886

Georges Seurat (1859-1891) was a French neo-impressionist painter. Despite dying at the age of only 31, Seurat had a profound impact on the art world: he took impressionism and made it scientific. Seurat relied on colour theory to break down the colours that he wanted to paint, and then build them up on a canvass by using thousands of tiny dots and brush strokes. Sunday on La Grande Jatte is a monumental painting, measuring 208 x 308 cms, and showing the wealthy Parisian elite enjoying the river Seine on a Sunday afternoon. Seurat spent two years preparing to execute the canvass, producing 30 sketches, 28 drawings and three large preparatory canvasses in the process. His complex composition shows 48 people, not to mention a few dogs and a monkey! The finished work is estimated to contain 220,000 dots of colour and is now found in Chicago's Institute of Art.

The Kiss – Gustav Klimt – 1907-8

Austrian painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) had an interesting personal life: he lived with his mother for his whole life, and had a string of lovers - often his models - with whom he fathered no fewer than 14 children! Strange, then, that Klimt would produce one of the iconic works of romantic love (sitting alongside Rodin's The Kiss). Klimt's masterpiece shows a man and woman locked in tender embrace. Though the man's face is almost completely obscured, note the way in which the models' hands wrap around each other, the patterns on their robes (rectangles depicting masculinity and fertility, flowers depicting the Ova), the amount of gold on the 6 x 6 foot canvass, and the flower meadow at the foot of the work. Virtually all of the painting is covered in gold leaf, perhaps in homage to Klimt's father (a goldsmith).

The Persistence of Memory – Salvador Dali – 1931

Spanish artist Salvador Dali (1904-1989) was one of the leading members of the surrealist movement. He was a controversial figure, being obsessed by dreams and death. He also had an odd artistic method: he would take micro-naps throughout the day, waking himself up as soon as he had nodded off by dropping a large key onto a plate; the idea was that he would then remember his dream. In The Persistence of Memory, we see Dali playing with his obsessions. Dreams are represented by watches (from the conscious world), painted realistically in some respects but taking on a fluid, plastic appearance - as they might in a dream. On the body of the desert floor is a strange white/pink structure, probably a representation of a sleeping Dali (if you look carefully you can see a closed eyelid). And the barren and decaying olive tree, and accurately painted orange pocket-watch on the bottom left being taken over by ants, symbolise death.