1. Backstage at the Opéra

Growing up in an affluential family, Degas was immersed in the music world of Paris from an early age.

His father, who worked in the family banking business, was responsible for hosting a musical salon on Mondays from the 1860s onwards. Here the family hosted informal concerts featuring works by Bach, Rameau and Gluck performed by both amateur and professional musicians.

In 1870, Désiré Dihau, a French bassoonist and composer from the Opéra, commissioned Degas to paint a set of portraits of the musicians from his father’s salon. This was the first introduction Degas had to the Opéra and its potential as a setting for his paintings.

In order to be granted access to the Opéra’s backstage, Degas appealed to his friend Albert Hecht, who was an influential art collector. In a letter from 1882, he wrote: “My dear Hecht, Have you the power to get the Opéra to give me a pass for the day of the dance examination, which, so I have been told, is to be on Thursday? I have done so many of these dance examinations without having seen them that I am a little ashamed of it.”

His request was granted and he was allowed into the inner realms of the Opéra, gradually becoming a regular fixture behind-the-scenes. His privileged access allowed him to observe the dancers off-stage. He observed first-hand the intense amount of energy and preparation that went into producing a stage performance.

While backstage at the Opéra, Degas spent many hours sketching the dancers. However, to execute his works he returned to his studio. He invited the dancers to pose for him, drawing on his imagination and memories to recreate scenes from the Opéra on canvas.

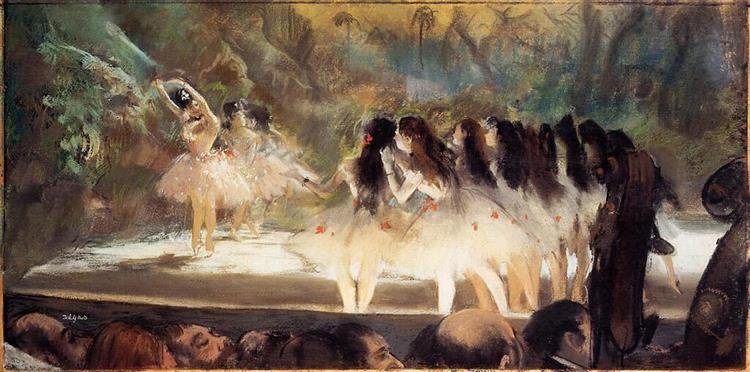

2. The Rue Peletier

Degas was acquainted with two different opera houses in Paris. The first was the original opera on the Rue Peletier but this venue was severely damaged by a fire in 1873.

As a result, a new opera house on the Palais Garnier became his primary focus from 1875 onwards.

Despite the change of venue, Degas continued to paint scenes from the Rue Peletier opera house long after it had been abandoned. The building had been constructed in 1820-21 to replace another house on the Rue de Richelieu which was destroyed following the assassination of the Duc de Berry in 1820. The original works the Degas began before the fire in 1873 were kept at this venue, remaining loyal to the Rue Peletier.

Echoes of the old venue continued throughout his later works too. The artist was not fond of the new opera house which he saw as too decorative and luxurious. It was also a political symbol of the Second Empire which Degas was strongly against.

3. Ballet in 19th century France

During Degas’ lifetime, the ballet was an immensely popular pastime. The Paris Opéra was seen as one of the leading symbols of France’s cultural superiority in the 19th century.

Indeed, the rise of ballet’s status in France began in 1661 when Louis XIV founded the Académie Royale de Dans.

Initially all the members of the ballet troupe were men. It was not until the 1830s that women started to be seen regularly on the ballet stage. From that period onwards, ballet was overtaken by Romanticism which transformed ballet dancers into emblems of femininity, both in France and England.

This shift was caused in part by the increasingly male audience and by the sexualisation of the female dancers. At the same time, the invention of the pointe shoe changed much of the dance technique, placing greater emphasis on the grace, lightness and elegance of the dancers. Before long, ballet became known as a woman’s profession and was deemed emasculating and inappropriate for men.

By the end of the 19th century, ballet had morphed into a highly feminised and eroticised form of entertainment. As the renowned critic and noted ballet reviewer Jules Janin wrote in the 1840s: “Speak to us of a pretty dancing girl who displays the grace of her features and the elegance of her figure, who reveals so fleetingly all the treasures of her beauty. […] I know what this lovely creature wishes us, and I would willingly follow her wherever she wishes in the sweet land of love.”

Thus, at the time when Degas was painting, there was a conflict between the ephemeral, feminine image of the ballet dancer and the blatantly titillating reputation the ballet had. Opera-goers knew that many of the dancers were also prostitutes or engaged in affairs with wealthy patrons of the opera. Dancers were usually from working class families and relied on the support of an influential ‘abonné’- a wealthy male subscription holder - to help them in their careers. This tension can be read in Degas’ work where he refused to shy away from the realities of the ballet world.

4. Degas’ observations

In his works, it is possible to note Degas’ appreciation of the dancers’ athleticism and strength.

While they are often portrayed wearing white dresses, in a hazy, magical light, Degas also carefully picks out details of their physique such as a muscular back or a stretched leg.

It is possible to track Degas’ fascination with movement throughout his career and it was aspect of the ballet that chiefly drew him to the subject. As he once described to Ambroise Vollard: ““People call me the painter of dancing girls […] It has never occurred to them that my chief interest in dancers lies in rendering movement and painting pretty clothes.”

Degas also had a particular interest in the unconscious poses of the dancers, leading him to seek out moments when the dancers were not on stage. In order to master the routines required of them, the dancers trained daily, having first begun dancing at a very young age. Even between rehearsals and performances, the dancers were constantly repeating and practicing, doing steps, stretches and adjusting their costumes.

In many of his paintings, Degas captures these habitual movements and repetitions. As he wrote: “it is necessary to do a subject ten times, a hundred times. Nothing in art must seem an accident”. Art historians have suggested that Degas felt a connection between his own art and that of the ballet dancers. In them, he saw an echo of his own beliefs: that hard work, repetition and practice are necessary to produce art that appears effortless.

As his friend, Paul Valéry described:

“[Degas was] divided against himself; on the one hand driven by an acute preoccupation with truth, eager for all the newly introduced and more or less felicitous ways of seeing things and of painting them; on the other hand possessed by a rigorous spirit of classicism, to whose principles of elegance, simplicity and style he devoted a lifetime of analysis.”

Perhaps it was this tension that lead Degas to capture images of the dancers at rest or in varying states of exhaustion. In an 1889 sonnet he wrote, “One knows that in your world / Queens are made of distance and greasepaint.” Rather than solely focussing on the spectacle of the ballet, he also depicted the physical effort involved.

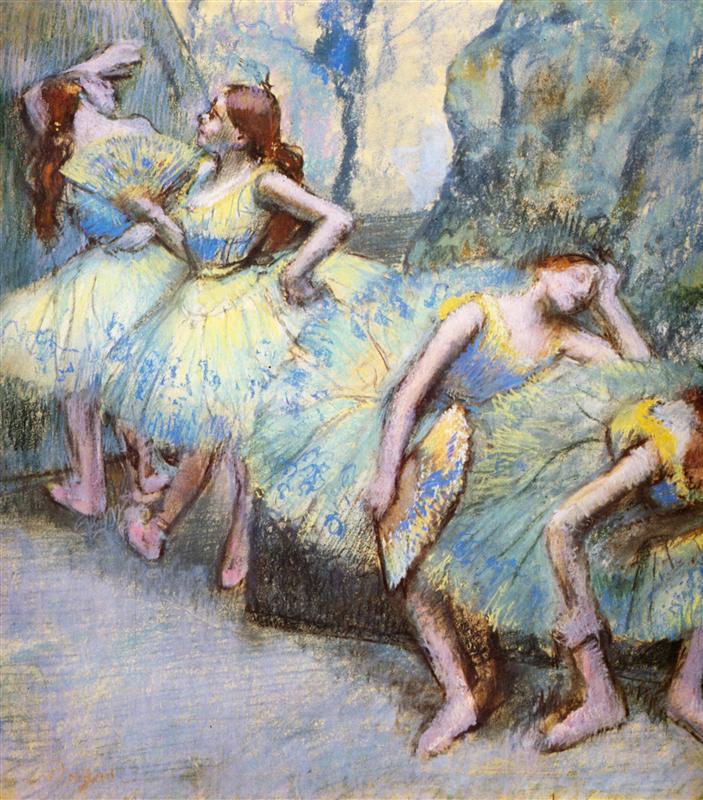

5. Oil paints, pastels and sculpture

The majority of Degas’ ballet dancer works are painted with oil on canvas. Many of his earlier paintings borrow from the Dutch academic style of painting, using smooth paint and light impasto.

These works were a commercial success and they granted Degas a steady stream of elite clientele.

In other works, Degas drew on Impressionist techniques to capture his Opéra scenes. In ‘Dancer Posing for a Photographer (Dancer in front of the Window)’ from 1875, a lone ballerina poses in front of a large window that looks out over a modern Parisian street. The dancer’s pose is unnatural and almost awkward, with one leg outstretched and en pointe, her arms lifted above her and her head tilted. The colours in the piece are cold, capturing the natural light of a grey winter morning. The brushstrokes are also more textured and more visible than other works.

As well as working on his oil paintings, Degas experimented heavily with pastels during the late 1880s. These explorations lead him to experiment with different colour techniques and ways of capturing light. As a result, many of his oil paintings take on a similar appearance to pastel drawings with plenty of powdery textures and subtle blending.

After visiting Degas in his studio in 1874, Edmond de Goncourt wrote in his diary “Out of all the subjects in modern life he has chosen washerwomen and ballet dancers […] it is a world of pink and white.” De Goncourt concluded that it was “the most delightful of pretexts for using pale, soft tints.”

Later, Degas began using bolder colours in his ballet dancer works. He developed a method of using numerous thick layers of pastels and warm, intense tones to capture the impressions of the dancers. He also began varying his brushstrokes to create almost abstract effects on the paper. He described these works to Julie Manet in 1899 as “orgies of colour.”

Degas also worked heavily in sculpture, working with the same themes of movement from his paintings and pastels. Undoubtedly the most famous of these is ‘Little Dancer Aged Fourteen’ (1880-81) depicting Marie Van Goethem, a dancer at the Paris Opéra.

However, he also produced many more wax figures such as ‘Dancer Looking at the Sole of her Right Foot’ from around 1895-1900 and ‘First Arabesque Penchée’, estimated to have been modelled before 1890. These sculptures all capture the dancers in strenuous poses, often balancing precipitously. Once again, Degas sought out the realism in the dancers’ lives rather than the most elegant or visually appealing poses.

6. Degas top 5 ballet dancer paintings

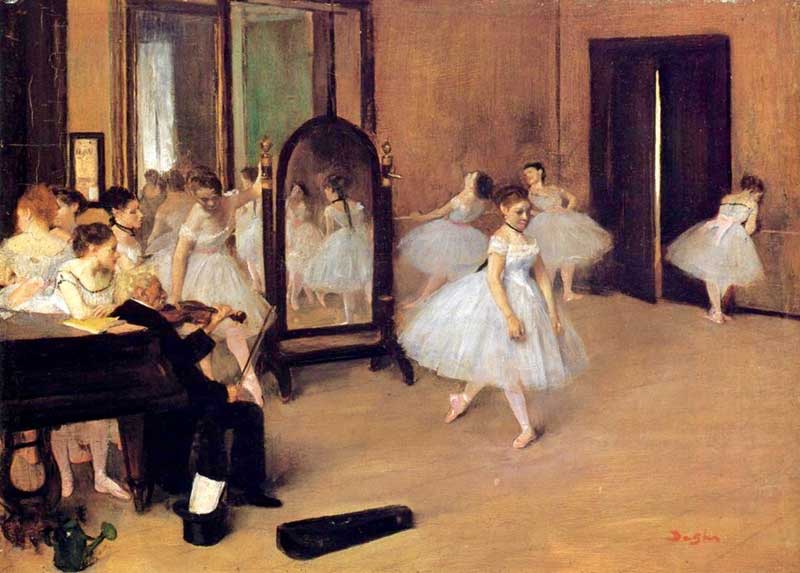

1. The Dancing Class (1870)

Degas’ first painting of a dance class, ‘The Dancing Class’ from 1870 was produced entirely in the artist’s studio. At this time, he did not have access to go backstage at the Paris Opéra so he had to content himself with painting entirely from his imagination.

To execute the piece, Degas brought young ballet dancers to his studio to pose as models. During these sessions, he also produced a large number of study drawings which went on to be used in other compositions. His interpretations of the “dance examinations” are completely unlike what such events would have looked like in reality. He invented the entire scene from his imagination.

A similar piece, from 1874, was commissioned by the singer Jean-Baptiste Faure. In this painting, twenty-four ballerinas and their mothers wait to dance for Jules Perrot, a well-known ballet master. On the wall of the studio, a poster of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell can be seen, referencing Faure’s illustrious career.

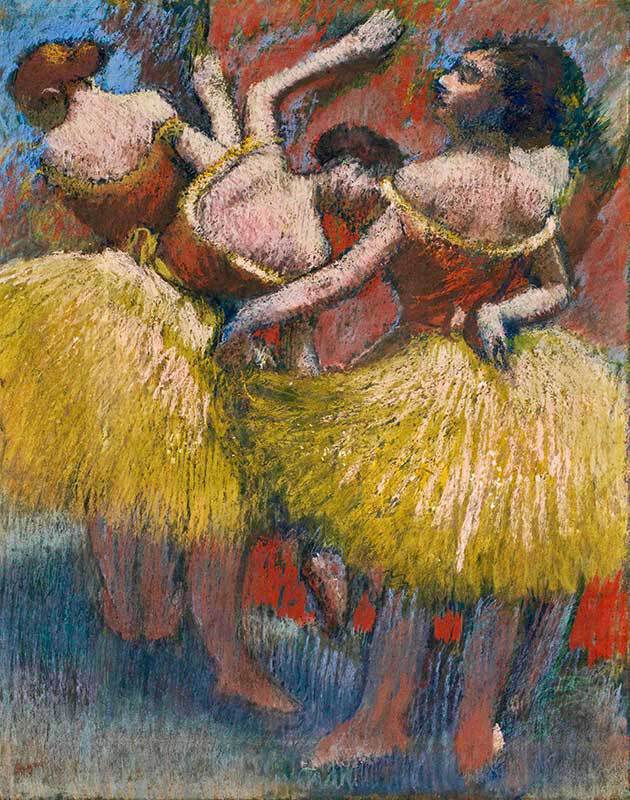

2. Three Dancers (1898)

This pastel on paper drawing from the late 1890s is an example of Degas’ semi-abstract technique of layering pastel crayon. The colours are intense, absorbing each of the individual dancers into a spectacle of colour.

Much of this drawing was also produced from Degas’ imagination. He placed the dancers in an unknown landscape, perhaps depicting the audience or the stage scenery. In particular, he highlights the colours of their costumes and their exposed backs and arms, once again emphasising the strength as well as the grace of the dancers.

Later in his career Degas began using far bolder colours, perhaps as a result of his deteriorating eyesight. Whatever the reason, the results are striking. Some notable examples include works like ‘The Red Ballet Skirts’ (1895-1900), ‘Three Dancers (Blue skirts, red tops)’ (1903) and ‘Three Dancers, Landscape Scenery’ (1895-98).

3. The Rehearsal (1874)

In this painting, the scene is dramatically cropped. A spiral staircase dominates the left side of the painting while the dancers are scattered sporadically through the space. Many of them have limbs cut off by the artist or are facing away from the viewer. This dramatic cropping was still highly unusual in European art at this time. It is likely that Degas, like many of the Impressionists, drew inspiration from Japanese prints for the composition.

In 1888, Theo Van Gogh, Vincent’s brother and a keen art collector, purchased this painting from Georges Petit for 5,220 French francs. Just a few weeks later he re-sold the work for 8,000 francs.

4. Dancers in the Classroom (1880)

This piece is an example of Degas’ experiments with elongated panels. He began exploring this format in 1879, using double square canvases to create compositions that he named “tableaux en long’. In all of the works, he constructed the piece along a diagonal line reaching from the lower corner to the opposite upper corner.

In this particular piece, Degas echoes the step-by-step motion of early chronophotography. The positions of the different dancers suggest one individual seen over a period of time, captured at various moments in the same rehearsal. There is also a noticeable amount of empty space in the piece which dominates the composition.

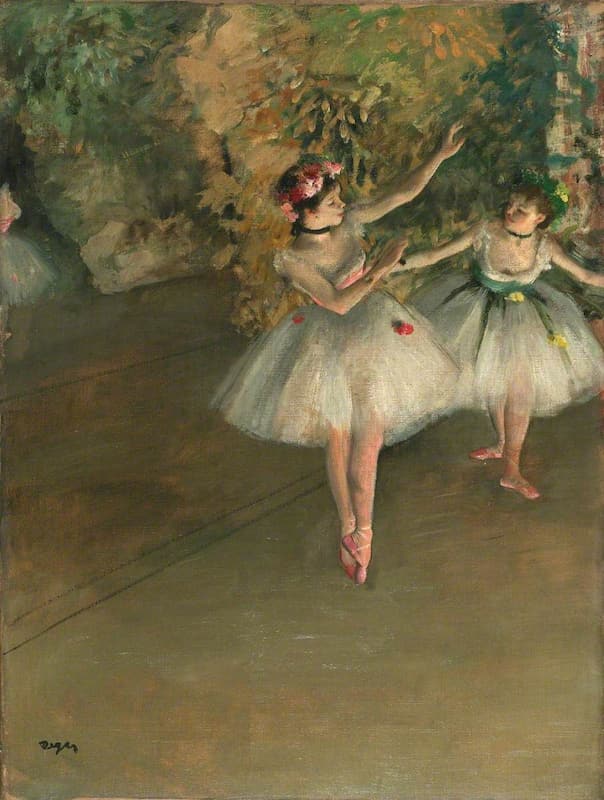

5. Two Dancers on the Stage (1874)

A hugely radical painting in the 1870s, this artwork was unprecedented when it was first produced. Depicting two dancers placed in an asymmetrical composition, the painting shocked the original viewers. Critics also expressed surprise at the dancers’ exposed flesh, described by one writer as “two ballet girls in filmy skirts, with rouge on their cheeks”, who “gyrate before the floodlights”.

This is one of very few paintings where Degas depicts the ballet dancers on-stage, in full costume, rather than waiting in the wings or in rehearsals. However, he chose not to depict one of the prima ballerinas of the day or the elegant audience in their finery. Instead, he opted for two chorus girls. One dancer can be seen en pointe and another bends down, smiling in the glow of the artificial lights.

The perspective of the painting is tilted, suggesting the influence of Japanese art. He also borrowed from the photographic gaze at a time when photography was in its infancy; the composition has the impression of being zoomed in.

Apart from the dancers, the rest of the piece is dominated by vacant space. This unusual composition was almost unheard of in the 19th century. Thus, Degas defied social and artistic norms, going against fashion and convention to produce something entirely original and daring. This is true of many of his ballet dancer works.