1. Monet's Cataract Problems

Claude Monet was predominantly a landscapist who painted in the bright sunshine outdoors.

It is therefore not surprising that he started to develop cataracts in 1912.

What are cataracts?

Cataracts are formed when the lens, a small see-through disc within your eye, develops cloudy patches. They are frequently seen in older people (Monet was 72 in 1912) and in those who work outdoors, especially when they have not had the benefit of modern uv-screening sunglasses.

Cataracts usually become bigger over time, causing a blurred, misty vision (a bit like trying to see through frosted bathroom glass). They normally appear in both eyes, although they don't develop at the same rate (Monet's right eye was always much worse than his left).

Cataracts can eventually cause blindness.

Monet's initial symptoms

Monet was diagnosed with cataracts in 1912. However, we know that Monet hated visiting doctors and so it is likely that his eyesight was impaired before this date.

By 1915, Monet's symptoms were getting more serious. We can date the worsening of his symptons with some accuracy because many of Monet's letters have been retained. In them he complained that:

"colours no longer have the same intensity for me. Reds have started to look muddy. My paintings are getting darker and darker"

"I am painting by relying on the labels on the tubes of paint and on the force of habit."

Things get worse in 1922

Monet's eyesight deteriorated significantly in 1922, when he was aged 82. The timing could not have been worse, as Monet had just agreed to paint and donate a series of huge water lily paintings to the French state.

To start with, Monet was in a state of denial. He tried to continue work, confessing to his friend Marc Elder that he had ruined several canvasses. On a subsequent trip to Giverny, Elder spotted canvasses that had been slashed by Monet's "angry hand" and learned that he had given servants instructions to burn yet more canvasses.

By September 1922 things had got so bad that Monet travelled to Paris to seek out one of the country's best ophthalmologists: Dr Charles Coutela. The results were not good. Coutela confirmed that Monet was legally blind in his right eye and had only 10% vision in his left.

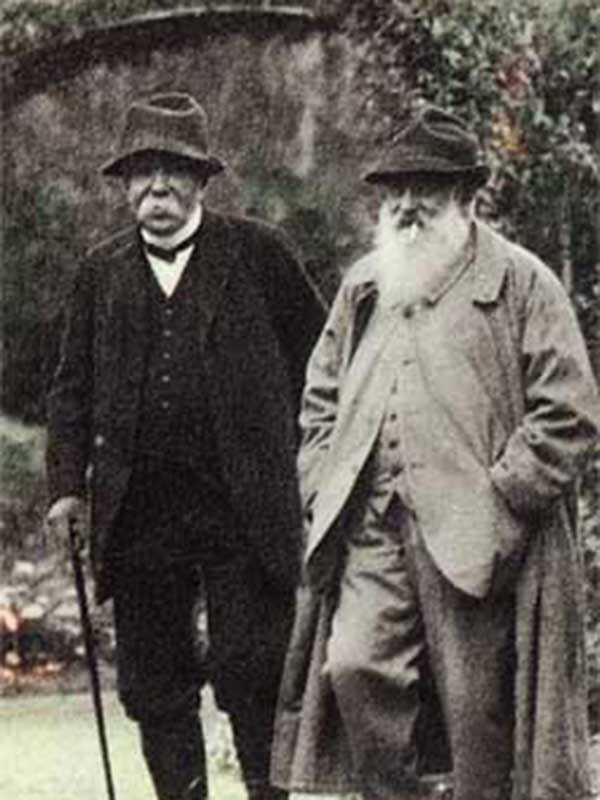

As Monet wrote to his friend, former French President Georges Clemenceau, the next day:

"Result: one eye completely gone, with an operation necessary and even unavoidable in the near future. Meanwhile, a course of treatment might improve the other eye and permit me to paint."

2. Monet's Eye Operations

Monet underwent three operations on his right eye in 1923. He was a terrible patient, refusing to follow orders and being moody and critical of his doctors in his recovery period.

At times, things got so bad that both his doctor and Clemenceau lost all patience with him!

The first two operations

Monet was first due to go under the knife in November 1922 but he chickened out. As he explained at the time, he was

"too afraid of the result".

But his eyesight continued to deteriorate and Monet relented, undergoing a first operation in January 1923 (an iridectomy, the removal of part of the iris of his right eye). The problem was that Monet had to convalesce by lying still in complete darkness for 10 days.

This he found impossible, ranting at one stage that blindness would be preferable to lying still.

In the event, Monet underwent a second extracapsular cataract extraction in early February 1923, finally being discharged after spending 38 days in Dr Coutela's eye clinic in Paris.

The third operation

Whilst Monet's close vision improved substantially (he could read 15-20 pages a day), his distance vision remained poor, especially outdoors.

He eventually agreed to further examination and, when a secondary cataract was diagnosed, he reluctantly agreed to a further operation. It took place in July 1923, this time in Giverny, and was substantially successful.

Despair and glasses

But Monet regarded the operation as a failure. He expected perfect vision to be restored immediately, and tried pair of spectacles after pair of spectacles to see if they would improve the position (never giving his eyes enough time to adjust to any one pair).

To make matters worse, he gave differing accounts of the problems he said remained with his vision, variously stating that: he could only see yellow and blue; that he saw everything in yellow; that he couldn't see yellow any more; and that he saw yellow as green and everything else as blue.

This was enough to drive Dr Coutela to despair. The poor eye specialist wrote to Clemenceau, explaining that:

"Monsieur Monet has made me go through such agony that I decided to pass on ... his second [left] eye."

Improvement

In about mid-1924, Monet had found himself another eye specialist - Dr Mawas - and had procured a pair of new Zeiss katral lenses designed for those recovering from cataract surgery. They improved Monet's sight substantially, allowing him to get back to putting the finishing touches to the Grand Decorations that he had promised to donate to the nation in 1922.

Grumpy old man

It was at this stage that Monet started complaining that his recovered eyesight had only served to demonstrate that he could no longer paint.

This time Clemenceau lost his patience completely. He sent a missive to Monet, explaining that:

It's irritating for you not to be able to complain about your sight after all of your wild lamentations. Fortunately, your work 'gives poor results', and therefore you can whine about that instead, because complaining gives you the greatest joy in life."

3. Monet's Art during the Cataract Years

Whilst it is impossible to know when Monet's cataracts started to affect his art, it is reasonable to assume that they worsened between 1915 and 1920 and had a very substantial effect from 1920-1924.

This can be seen in Monet's art over that period.

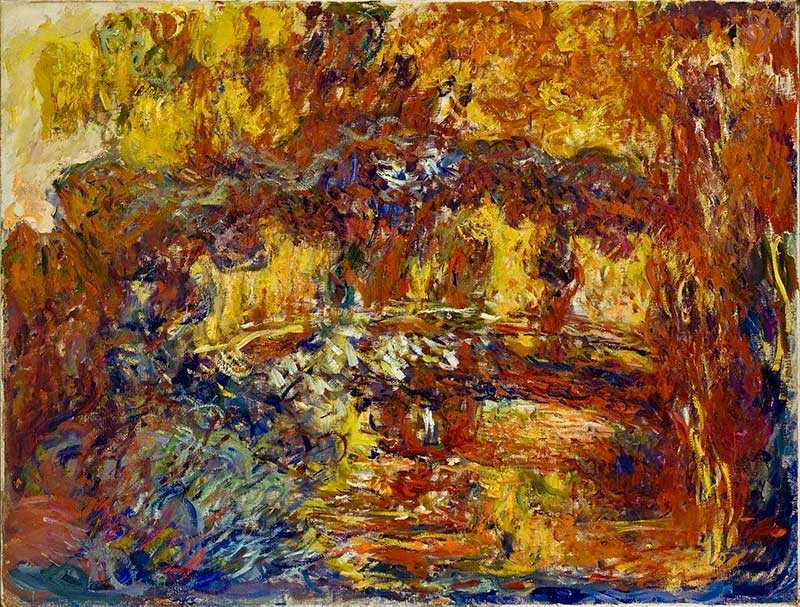

Two examples of Monet's Japanese Footbridge

The first painting shown in this section is of Monet's The Japanese Footbridge, completed in 1922 (ie at a time when cataracts were substantially impairing Monet's vision). The structure of the footbridge is just about visible, at least to those who know what they are looking for.

But the rest of the painting is a remarkably abstracted work of attention-grabbing oranges, yellows, reds and blues.

This is to be contrasted with the second picture shown in this section, another version of Monet's Japanese Footbridge, but this time one completed in 1899 - when Monet was 59 and had no documented problems with his eyesight.

Other examples

It is fair to say that Monet's art did become more abstract over time, and that this was probably down to artistic development rather than illness.

But the differences between his Japanese Footbridge examples explained above are so significant that they can only reasonably be attributed to Monet's eyesight.

The change in Monet's work is also evident from looking at Rose Way at Giverny (the third picture in this section). This was another canvass completed in 1922, at the height of Monet's problems with his eyes. The subject matter would probably not be clear to a viewer who did not know the painting's title.