1. Coming to and living in Paris

In the early 1860s, the key impressionists converged on Paris and slowly became friends.

Coming to Paris

Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas were born and grew up in Paris. As for the remaining four members of the core impressionist group:

- Auguste Renoir was born in Limoges in 1841 but came to Paris with his parents at a young age. He was an apprentice porcelain painter in the late 1850s, and applied to become a copyist in the Louvre in 1860.

- Claude Monet was born in Paris but moved with his family to Le Havre in Normandy when he was a young child. He returned to Paris in May 1859, but left again to do his military service in 1861. He returned to Paris for good in November 1862.

- Paul Cezanne was born and brought up in Aix-en-Provence, in the south of France. He wanted to follow his childhood friend Emile Zola to Paris in 1860, but his father persuaded him to study law first. That was a complete failure and Cezanne hen-pecked his father into letting him go the next year.

- Camille Pissarro was born in the Dutch West Indies in 1830 and, after dabbling in painting there, arrived in Paris in 1855.

Paris

Paris looked very different to the shining, open-plan network of wide streets and boulevards that would feature regularly in later Impressionist paintings.

The city was dark and dingy, lacking even a working sewage system.

Seven years earlier, Baron Haussmann had been elected Prefect of the Seine and had begun making plans to modernise the city but it was very much a work in progress. One of his first actions was to tear down the inner city wall, opening up the suburbs surrounding Paris and making them part of the city.

The newly connected suburb of Montmartre was a favourite among artists. They gathered in the cafes and brasseries that huddled together in the still largely rural district, chatting and socialising. This was the setting in which the strong social bonds that allowed the impressionists to support each other developed.

This is not to say that all the impressionists lived a hand-to-mouth Bohemian existence. This was certainly the lot of Monet, Pissarro and Renoir. But Cezanne, Degas and Manet had family money behind them—and Manet often doled it out to others in the group when times got tough.

2. The role of the École des Beaux-Arts

In the 1860s, the École des Beaux-Arts, part of the Institut de France, was responsible for dictating how art should be made and what kind of subjects were to be painted.

Art students received classical training and were expected to focus on traditional subjects, as well as learning meticulous anatomy drawing. This particular branch of their training was achieved through the careful study of human corpses, lent by the Medical School.

Rigidity

In this rigid and exacting setting, paintings were limited to a very narrow range of subject matter. The Paris Salon gave pride of place to artworks depicting historical scenes, mythology, or moral lessons taken from the bible. Similarly, images capturing moments from great literature like Shakespeare, Byron or Sir Walter Scott were also permitted, as well as works demonstrating the glory and valour of the French nation.

Salon favourites

Some of the most popular artists, all Salon favourites, were Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and Gustave Moreau. These painters followed the expectations of the Institut in their themes and even in their style, which was also governed by the École des Beaux-Arts.

Their work was finely painted using extreme detail. The brushworks were invisible and the light and colour palette of the paintings drew on the technique of contrasts - lightness for high drama, darkness for grandeur and solemnity.

Delacroix

The only rogue among them was Eugène Delacroix, whose intense colour palette and quick, expressive brushstrokes were seen as radical to the art establishment and audiences who came to the Salon. Nonetheless, Delacroix did not push the boundaries beyond the upper limits of acceptability and, thus, he did not fall foul of the Institut de France.

He was daring but not so daring that he risked being excluded from the Salon.

3. The Studios of Suisse and Gleyre

At the age of 15, Monet was already making a living from his art, charging commercial rates to sketch caricatures of local dignitaries in Le Havre, Normandy.

When he moved to Paris, he began attending the studio of Charles Suisse in order to improve his academic painting technique.

Life in Suisse's studio

Suisse did not provide any formal training or examinations, but his studio was a space in which Monet could paint. He was surrounded by other artists and was able to draw off their ideas, along with the supervision of a one-time academy artist.

It was here that Monet met Pissarro.

Pissarro would attend the studio in the evenings, preferring to paint outside, in the landscape around Paris during the day. He was captivated by the changing light on the River Seine and the fields and villages that bordered it. In 1859, the same year Monet arrived in Paris, Pissarro had had his first painting accepted by the Salon, which spurred his dream of becoming a professional painter and ideally a landscapist.

In 1861, Cézanne also arrived at the studio of Suisse. He was awkward and clumsy, with a brooding manner. Adding to his unusual character was his style of drawing, which was ridiculed by some of the other students in the studio.

Cézanne had been convinced to move to Paris by his closest childhood friend, Emile Zola, and it may have been Zola who convinced him to enrol at Suisse’s studio. Monet was already in Algiers by the time Cézanne began attending sessions, having been drafted into the army. Consequently, it was Pissarro who first fostered a friendship with the strange artist from Aix.

Both Pissarro and Zola supported Cézanne, who was chronically insecure about his work and repeatedly threatened to give up on painting and return to his home in the south of France. On one occasion, he did so and took a job as a cashier in his father's bank, but he lasted only a year before returning once more to Paris and Suisse’s studio.

Gleyre’s Studio

Following his release from the army in 1862 on the grounds of sickness (he contracted typhoid fever in Algeria), Monet began attending the studio of Charles Gleyre.

Gleyre was more academic in his teaching style than Suisse and he was able to draw on a rather more prestigious reputation than Monet’s former teacher. As a result, Gleyre’s studio attracted a more affluent class of students, which Monet enjoyed as it gave him more opportunities to show off.

One of the quieter members of the 40 or so students who attended the studio was Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Young Renoir had first started drawing as a very young boy, using his father’s tailor’s chalk to sketch on the floor.

By the age of 13, he began work as a porcelain painter, paid by the amount of crockery he produced. In both this job and the next, as a painter of blinds, he showed himself to be a savvier artist than many others, painting quickly and including lots of fluffy clouds in his compositions to complete the works faster. His brother-in-law helped him buy his first set of oil paints and an easel and Renoir enrolled in Gleyre’s academy.

Similarly, Alfred Sisley was a regular attendee of Gleyre’s studio. Unlike the majority of his fellow Frenchmen (and women, as unusually for the time there were three women at Gleyre’s studio), Sisley had been inspired to paint after seeing the work of John Constable and J.M.W. Turner at the National Gallery in London. As the son of an English merchant, he had lived in London for four years whilst working for the family business.

Friendship blossoms

In this convivial setting, where the students painted male models for three weeks of the month and female models for one week, Monet, Renoir and Sisley became close friends.

They were somewhat set apart from the other students, who were most young men from wealthy families, dressed fashionably in the studied style of a ‘bohemian painter’. Monet called the rest of the cohort “the grocers” because of their narrow-minded approach to art.

During days spent in the studio, smoking, joking and flirting with the female models, the trio also got to know another member of the academy: Frédéric Bazille.

Bazille was wealthy and well-bred but terribly shy. When he was not working studiously under Gleyre, he was taking classes at the École de Médecine where he was studying to become a doctor. Renoir’s first assumption of him was

“the sort who’d have his valet break in his new shoes for him”.

Gleyre's method

All the artists initially learnt to paint in Gleyre’s Neo-Classical style. They studied how to draw nude figures in extreme detail, receiving prizes for perspective and anatomy, among other things.

A quote from Monet, describing Gleyre’s comments on one of his sketches, gives an indication of his method of teaching:

“Not bad, not bad at all, this business here. But it is too much about this particular model. You have a heavyset man. He has huge feet, which you depict as such. It’s all very ugly. So remember young man, when we draw a figure, we must always keep in mind the antique. Nature, my friend, is a very admirable aspect of research, but it provides no interest.”

Thankfully, the group did not pay too much attention to their teacher’s opinions. Bazille reportedly said to Renoir when they first met,

“Large-scale classical compositions are over. The spectacle of everyday life is more fascinating."

4. The start of impressionism

Whilst studying at Gleyre’s, Renoir ran out of money and he was forced to start painting porcelain again.

Money worries

In the meantime, he and Monet also pooled what little money they had to rent lodgings, pay a model and buy art supplies.

In this tiny space, they painted portraits of tradespeople, sought out and charmed by Monet. They used any money they earned for their living costs. This included buying fuel for their stove so that they could cook food and help the models to stop shivering. A grocer who sat for their paintings gave them a sack of beans as payment, which they were able to live off for a month.

In this setting, Cézanne was introduced to the group by Pissarro and he was welcomed as a friend to their makeshift studio. One day he was excited to announce that he had found someone to purchase one of his paintings, as he was carrying the newly painted work down the rue de la Rouchefoucauld. “I said, ‘If you like it, you can have it’”, he told Monet and Renoir:

“Well he can’t afford to pay me, but he’s taken the painting, I insisted.”

Enter Edouard Manet

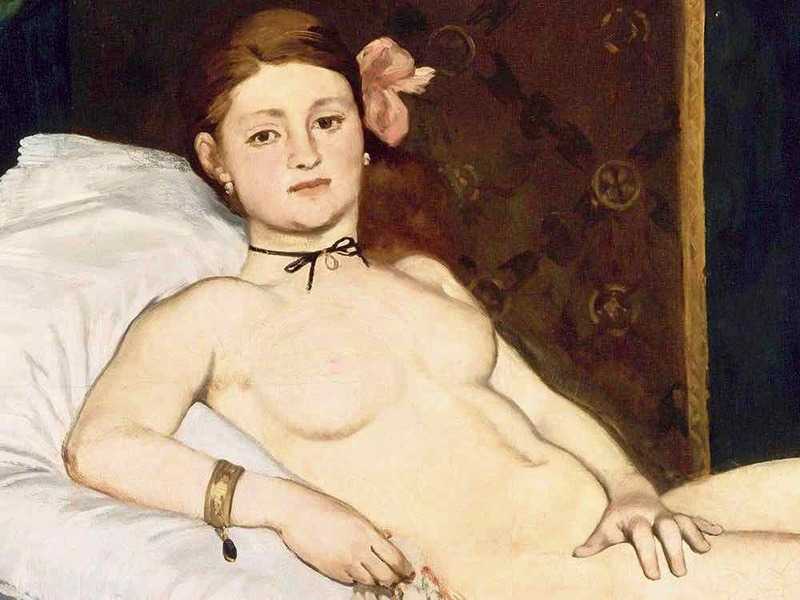

The group were first met Édouard Manet through his painting. Manet’s work was one of over 800 paintings exhibited in the Salon des Refusés or ‘exhibition of rejects’ in 1863. This show was organised on the demand of Napoleon III, who feared political backlash from the uproar around the Salon’s selection of only a small, select group of artists.

In the Salon des Refusés, visitors flocked to mock the paintings on show. Of these, one stood out as the most outrageous of them all: Manet’s ‘Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe' or ‘Luncheon on the Grass’ from 1862-63. The naked woman who stared straight out of the artwork was one of the most shocking elements, but so too was the casual way in which the two men were seated next to her, dressed in modern clothes.

The critics were shocked. For example one wrote:

This painting is Manet's idea of a practical joke.

The painting was a reflection of everyday life. This made it revolutionary for an audience who had only ever seen history or myth depicted in paintings. Manet immediately became a fashionable, roguish celebrity in Parisian society and he was frequently invited to dinner parties and soirées.

Like countless others, the students of Gleyre’s studio rushed to see the artwork that had caused such a stir. In this work, they saw a reflection of what they wanted to achieve, moving away from classical subjects and towards ordinary life.

In fact, Bazille already knew Manet and Monet knew his brother, Gustave, but the group were not acquainted with Édouard Manet. They would not be for some time. Instead, he existed for them as something of an aspirational figure, an object of their imaginations and their conversations.

Moving in far wealthier circles than the group of landscapists and working-class portraitists, Manet was instead friends with the likes of Henri Fantin-Latour and Alfred Stevens. It was in the Louvre that he first became acquainted with Edgar Degas in 1863, who he also knew from the bars and cafes they both visited in Pigalle. They became friends thanks to their shared intellect, rather than their shared interest in painting where their views differed enormously.

Working en plein air

The warm spring of 1863 convinced the group to follow Cézanne and Zola out to the countryside.

The pair were already venturing outside Paris regularly, taking the train on Sunday mornings out to Fontenay-aux-Roses and walking to any wide green space of their choosing where they could spend the day reading and painting.

Monet, Renoir, Sisley and Bazille began going with them, travelling as far as Melun, which lay to the North of the Forest of Fountainebleu. In doing so, they were following in the footsteps of the Barbizon School of painters, who had first made the journey in order to capture the natural beauty of the landscape, before finishing their paintings in the studio. Similarly, Pissarro had already been making regular trips to the area for his landscape works.

One artist who had also begun working outdoors more frequently was a young Berthe Morisot. She was not acquainted with the group, however. Rather than Gleyre’s studio, Morisot had been attending classes by Geoffroy-Alphonse Chocarne with her sisters.

Unfortunately, Chocarne was slow and incredibly boring and so she had begged to be allowed to change to a different tutor. Her demand was heard and she began studying under Joseph Guichard before being recommended to Camille Corot, who had also served as a mentor to Pissarro.

Under Corot’s supervision, Morisot began travelling into the countryside in order to paint in nature. Her landscapes were well-received and she spent two consecutive summers working on her technique en plein air in Normandy.

It was not until 1868 that Morisot was introduced to Manet through their mutual acquaintance Henri Fantin-Latour, whilst she sat sketching at the Louvre. Accordingly, Morisot was then introduced to Degas at a soirée, a regular feature in the social lives of the Parisian elite. Morisot would be the first to convince Manet that he should attempt to paint outdoors, rather than staying locked in his studio.

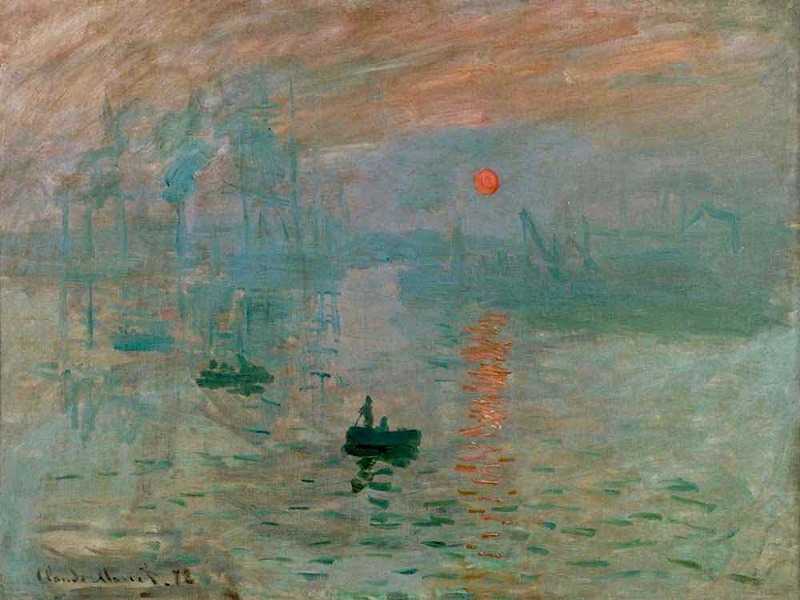

The First Impressionist Exhibition

When the Impressionists held their first independent exhibition in 1874, they had had over a decade of honing their skill as artists. The work they produced for the First Impressionist Exhibition was borne out of endless threads of inspiration and intrigue that had interwoven through their separate journeys and fed into their collective ideas as a group.

Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Degas, Cézanne, and Morisot - Manet refused to take part in any of the independent exhibitions - were incredibly diverse, in their backgrounds, characteristics and their artistic style. They had met one another largely through chance but they came together under a common cause, which later became known as Impressionism.

It was their independence that set them apart from the thousands of other art students attempting to find their way in Paris in the 19th century. As a group, they had tried to find an alternative way of painting that did not yield to the demands of the Institut de France. The start of the Impressionist period was a slow, gradual evolution from the established norms in French art towards something freer and more alive. As the movement gathered momentum, it would develop into a period of immense flux in European culture for decades to come.