1. Manet: A Brief Bio

Manet was born in Paris on 23rd January 1832, the son of a wealthy judge and a diplomat’s daughter.

He had a privileged childhood, growing up in an affluent suburb of Paris. As he got older, he became acquainted with many prominent members of Parisian society through his parents’ connections.

Manet's parents

Contrary to his parent’s wishes, Manet wanted to become an artist. Supported in his ambitions by his uncle, Edmond Fournier, Manet would visit the Louvre to study the works of the old Masters. However, his father insisted that he take up a reputable profession, first encouraging him to study law and later enlisting him in the Navy.

After failing his naval exams in 1849 and continuing to fail his retakes, his parents eventually agreed to let Manet go to art school. Manet’s earliest art training was under Antonin Proust. He began taking drawing classes in 1845, learning from the artist’s academic style. Proust went on to become the Minister of Fine Arts and remained a close acquaintance of Manet’s throughout his career.

Learning to paint

With his parents’ blessing, Manet also began studying fine art painting with Thomas Couture, an academic painter. Manet was taught by Couture between 1850 and 1856 where he learnt the art of history painting. He also continued to do his own study in the Louvre, spending hours copying and sketching great masterpieces. According to Proust,

"he was constantly searching for an immediate passage from shade into light. The luminous shadows of Titian filled him with enthusiasm. He went wild over the Old Masters.”

A grand tour

Like many young artists from affluent families, Manet took a tour of Europe to further his painting studies. From 1853 to 1856, he left France to travel, going through Italy, up to Germany and to Holland: three great destinations for young aspiring painters. During his travels, he was able to study the works of highly regarded artists such as Frans Hals and Francisco José de Goya.

As well as studying classical painting, Manet also developed an interest in paintings of everyday life. From the mid-1860s onwards, he abandoned history painting and religious subjects altogether, preferring to focus on Realist style works. ‘Absinthe Drinker’ from 1859 is one of the earliest examples of his experiments with Realism. This painting was rejected from the Salon.

Meeting the impressionists

After meeting Edgar Degas at the Louvre in 1861, the two artists developed a close professional relationship, having heated discussions surrounding the meaning of art. Through Degas, Manet met Morisot and some years later he was introduced to the rest of the Impressionist artists.

Manet is generally regarded as one of the founders of Impressionism, despite distancing himself from the group at a professional level. He remained caught between the art establishment, the world of the Salon, and the independent Impressionists.

Two years before his death, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. He died at a young age, in 1883, leaving a hole in the Impressionist movement that affected the other artists very deeply.

2. No, Manet was not an Impressionist

Manet began making a name for himself long before the Impressionist movement began.

As a result of his upper-middle-class upbringing, Manet moved in influential circles. This meant that his paintings gathered attention even before he became a well-known artist.

Luncheon on the Grass

One of Manet’s most famous paintings from this early period is ‘The Luncheon on the Grass’ from 1863. This work features a nude woman seated next to two men in contemporary dress. The painting caused outrage for its casual depiction of nakedness outside of a classical setting, due in part to the connotations of modern-day prostitution.

This work was breaking boundaries before the Impressionists had begun to paint in their unique style. In fact, the artists of the Impressionist movement, including Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley, were so amazed by Manet’s work that they went to see it themselves.

This controversial artist, who was not afraid of being extremely bold in his contemporary subject matter, became a huge source of inspiration for the young Impressionists. Manet gave them something to aim towards, an example of the modern paintings that they longed to produce.

1. Manet and Realism

Far from being one of the Impressionists, Manet was closely associated with the Realist movement in his early career. Realism was the most fashionable art movement for young artists at the time and the Realist style can be seen in many of Manet’s works from the 1860s. ‘The Spanish Singer’ from 1865 is one such example, picturing a street singer who was actually a model that Manet dressed and posed in a studio.

In his experiments with Realism, Manet began developing a new painting technique that allowed him to paint faster and freer. Instead of building up careful layers, he would apply the paint to the canvas more quickly, scraping away all the paint right down to the canvas when he needed to make an alteration.

He also began painting in blocks of colour, creating stark contrasts between different colours rather than applying gentler shades. These sudden transitions can be seen in many of his still life works including ‘Still Life with Melons and Peaches’ from 1866. The colour effect gave Manet’s paintings a confident, modern style that was very different to the academic conventions he had been taught.

The Impressionists borrowed from Manet’s stylistic experiments, turning his blocks of contrasting colour into smaller flecks and daubs. This technique combined different colour effects that had come before, drawing on work by Delacroix in particular. It helped the Impressionists to create their mottled paintings, which they later became famous for.

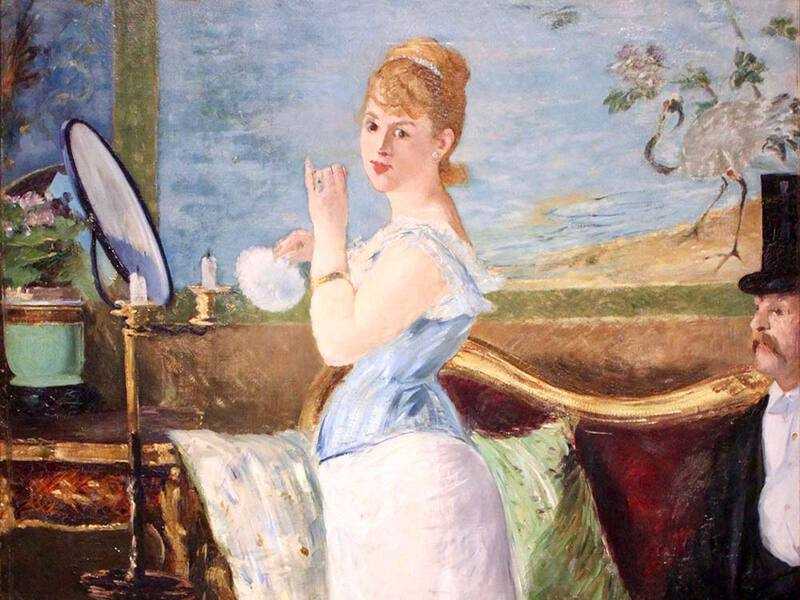

2. Use of the colour Black

One of the most crucial rifts between Manet and the other Impressionists, however, was his use of pure black in his paintings.

Unlike Impressionist artists including Monet and Pissarro, who sought to do away with black altogether, Manet favoured black as a way to add drama to his paintings. Consequently, many of Manet’s paintings contrast heavily with the light, pastel palettes more typical of the Impressionist style.

This technique is evident in paintings like ‘Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets’ from 1872. Manet’s painting uses dramatic light effects to create contrast, lighting Morisot’s face from one side. As a result, the work becomes a striking show of light and dark, with even her pale green eyes depicted as black.

It is possible that this painting was made to convince Morisot of the value of black as her work during this period was becoming ever lighter and more Impressionistic. It may also have been simply an attempt to capture the “Spanish beauty” of his brother’s fiancé.

Many of his Manet’s contemporaries praised the painting as being one of his masterpieces. Paul Valery, writing in 1932, agreed:

"I do not rank anything in Manet's work higher than a certain portrait of Berthe Morisot dated 1872”.

3. The Impressionist Exhibitions

Another significant boundary between Manet and the other Impressionist artists was his refusal to take part in any of the independent impressionist exhibitions. Manet did not wish to be associated with the Impressionist movement, preferring to be seen as an independent artist.

Despite his close ties with many of the artists, he did not support their aims of breaking free from the Salon and the mainstream art establishment.

The key difference was that Manet was not in need of the commercial support that the others hoped the exhibitions would provide. He had established a name for himself in Paris, particularly among the middle classes, and he was able to sell a number of paintings thanks to these connections.

More importantly, he also came from a wealthy family and did not struggle with his finances in the way that artists such as Pissarro, Sisley and Renoir did.

These factors all suggest that Manet was not an Impressionist, despite his close ties with many members of the group. His lack of support for the Impressionist exhibitions was an important demonstration of his desire for independence.

3. Yes, Manet was an Impressionist

In the cafes of Montmartre, Manet became closely acquainted with many artists who would later form the Impressionist movement.

Monet, Renoir and Pissarro became close friends of Manet. In these informal spaces, the Impressionist artists formulated a plan for a new art style, laying out their hopes for the future.

1. Manet the Unofficial Leader

The young artists wanted to break away from the rigid restrictions of academic painting and paint real life in a raw, more immediate way. As the more famous member of the group, Manet became the unofficial head. He cultivated a group of eager artists, pushing for innovation and experimentation in their work.

Manet also fostered close relationships with Edgar Degas and Berthe Morisot. These collaborations were extremely significant for Manet. Both artists inspired Manet’s artistic development and in turn, he influenced theirs.

Manet's unofficial leadership can be seen by this 1870 painting by Henri Fantin-Latour called Un Atelier aux Batignolles (A Studio in the Batignolles). It shows Manet painting with Renoir, Bazille and Monet looking on.

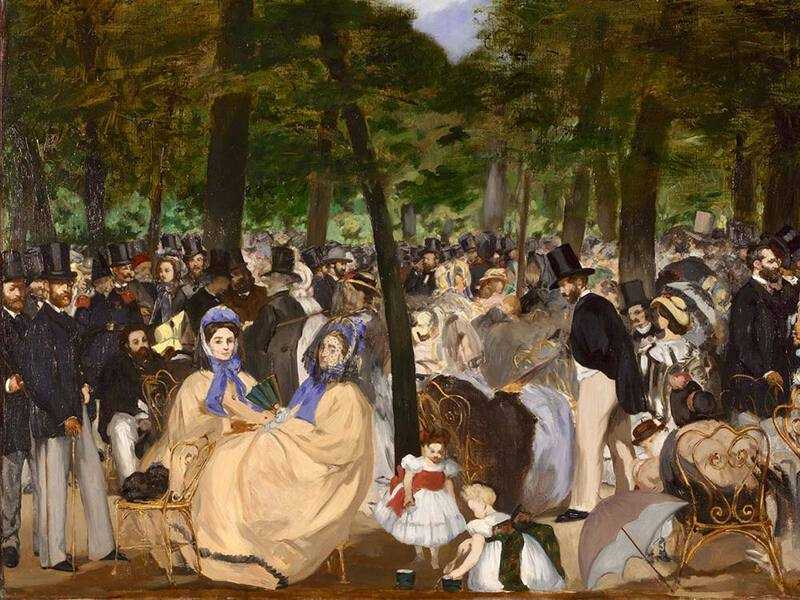

2. Ordinary Life

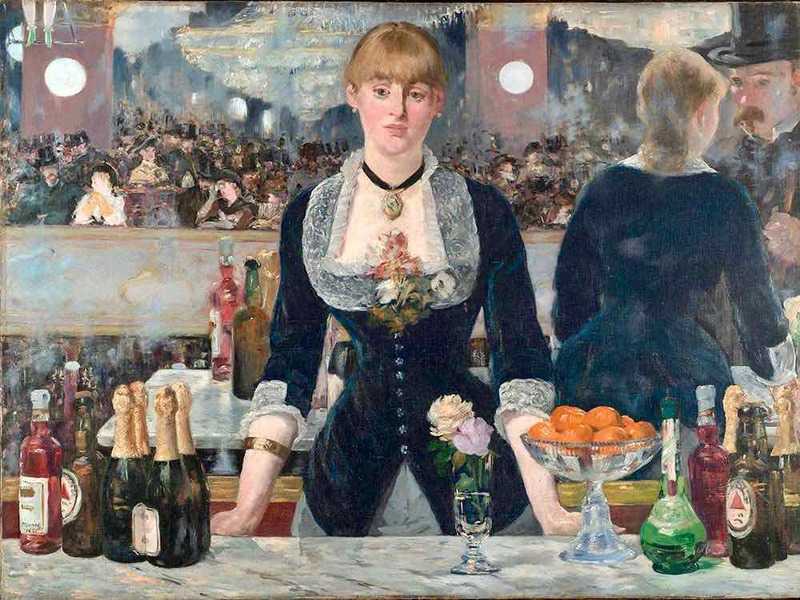

What the Impressionists shared was a desire to paint ordinary life and the scenes they saw around them. Manet was a huge advocate of this aim and he produced countless paintings of working-class individuals, from street singers to barmaids to workmen.

Through the influence of the other Impressionist artists, his work moved from Realism towards a more Impressionist style, gradually becoming freer and more experimental. With Berthe Morisot’s guidance, he also started painting en plein air.

These points are demonstrated by Manet's The Seine at Argenteuil (1874), which could to an untrained eye be mistaken for a work by Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

3. Unfinished Works

The relationship Manet had with Impressionism can perhaps best be seen in his use of brushstrokes. Unlike many Realist painters, Manet favoured looser, more feathered brushstrokes that convey emotion in his works. He cultivated an unstudied aesthetic, often leaving areas of blank canvas, and ignored the critics who said his paintings looked “unfinished”.

The influence of the Impressionist style is evident in later paintings like ‘Roadmenders’ from 1878, which shows a street in Paris with workers in the foreground. The ‘Roadmenders’ was painted from two preliminary sketches but the stylistic methods Manet used to create the work are deliberately Impressionist, implying spontaneity.

The brushstrokes are quick and loose, creating a sense of haziness. The use of natural light is also classic of the Impressionist style, suggesting that this work was painted en plein air.

What sets ‘Roadmenders’ apart from Realist paintings, which depicted similar subjects, is that none of the figures are individualised. The men are simply figures rather than faces demonstrating the gritty reality of life in manual labour. Instead of a grim painting of real people, Manet captures a scene of lightness and movement, he focusses on the street as a whole rather than the people at work.

Hence, whilst Manet did not adopt all of the conventions of the Impressionist movement, it is clear from his colour palette and his brushwork that the Impressionist style had a significant effect on him. Even the darker colours in many of his paintings are made up of lighter hues.

4. Pastoral Care

He helped to push the Impressionist movement forward, encouraging many of the artists and Morisot in particular. Manet also doled out money to the impressionists, in particular Claude Monet, when they were in dire financial straits.

Furthermore, Manet was one of the core members of a group of artists, writers and intellectuals who frequented Parisian cafes to debate art, politics and life. This was another way in which the impressionist group's relationship was solidified.

At the same time, Manet helped the Impressionists to gain a reputation for themselves, partly thanks to his controversial paintings and reputation in Parisian society.

Though Manet maintained close ties with the Impressionist movement, he did prefer to distance himself from Impressionism in order to increase his chances of being accepted into the Salon. Hence, he did not take part in the Impressionist exhibitions, even though his private letters suggest that he would have liked to.

4. Manet and Impressionism

The relationship Manet had with the Impressionist movement in an intriguing one.

Through his career, his painting style changed significantly, often varying from year to year and even from one work to the next.

What is clear is that Manet was heavily inspired by his relationship with the other Impressionist artists. He thrived on discussions and debates among intellectuals. Many of the central ideas of the Impressionist movement were born from conversations in cafes and cabarets around Paris and hence, Manet was a central figure in the development of the Impressionist movement.

As well as the social and intellectual aspects of these relationships, Manet also absorbed many of the stylistic features of the Impressionist movement into his painting. This is seen most clearly in his brushstrokes and his choice of subject matter, both of which were highly contemporary.

Drawing on the work of Eugene Delacroix and collaborating with other Impressionist artists, Manet regularly experimented with colour theory in his paintings. He adopted the technique of optical mixing, using a wide range of colours on his canvas in order to build up certain colour blocks rather than using pre-mixed paint. He also experimented with contrasting colours in his works.

On the other hand, Manet took care to distance himself from the Impressionist movement in order to avoid damaging his reputation. Unlike Pissarro, for instance, who saw his career tied to the success of the movement as a whole, Manet was extremely independent. This was no doubt motivated by his upbringing, which gave him financial independence and imbued him with an air of confidence and social adaptability. However, it is also evidence of Manet’s desire to win recognition for his art through official channels.

Manet was not content to simply make art for art’s sake. He wanted the prestige that came with being a Salon recognised artist. At the same time, he was not afraid of causing a stir and ruffling feathers with his choice of subject matter. From prostitutes to alcoholics, Manet favoured images of ordinary life, which he painted into works that shocked and titillated audiences.

He was a highly literate painter, borrowing symbols from the classical painting tradition to connote things to his audience. Carefully placed objects, figures and clothing allowed Manet to construct complicated, and often brazen, stories behind the images he painted. This covert painting style meant that he quickly gained notoriety and fame.

Hence, Manet courted controversy in his art, his lifestyle and his ambition. These elements made him singularly independent but also made him an Impressionist. His desire to paint ordinary life, albeit in a studied and calculated way, tied him to the movement, even though he denied the connections. He is now rightly seen as one of the key artists of Impressionism.