1. The ‘Haystacks’ Series

We have tracked down images of as many of the Haystacks series as we can, presented below.

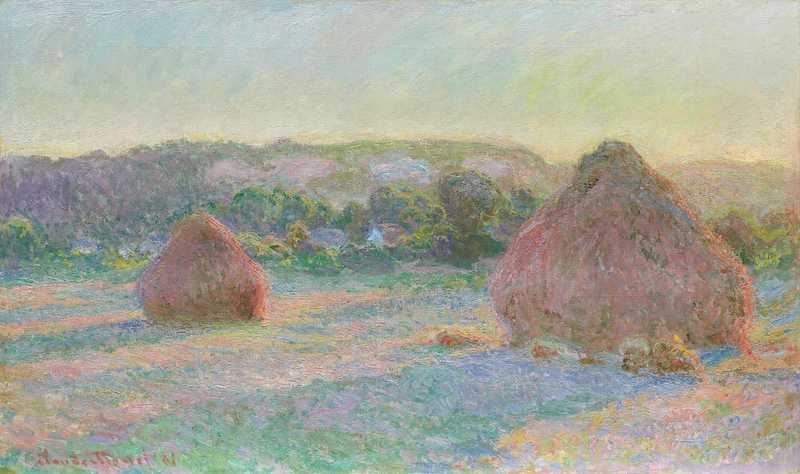

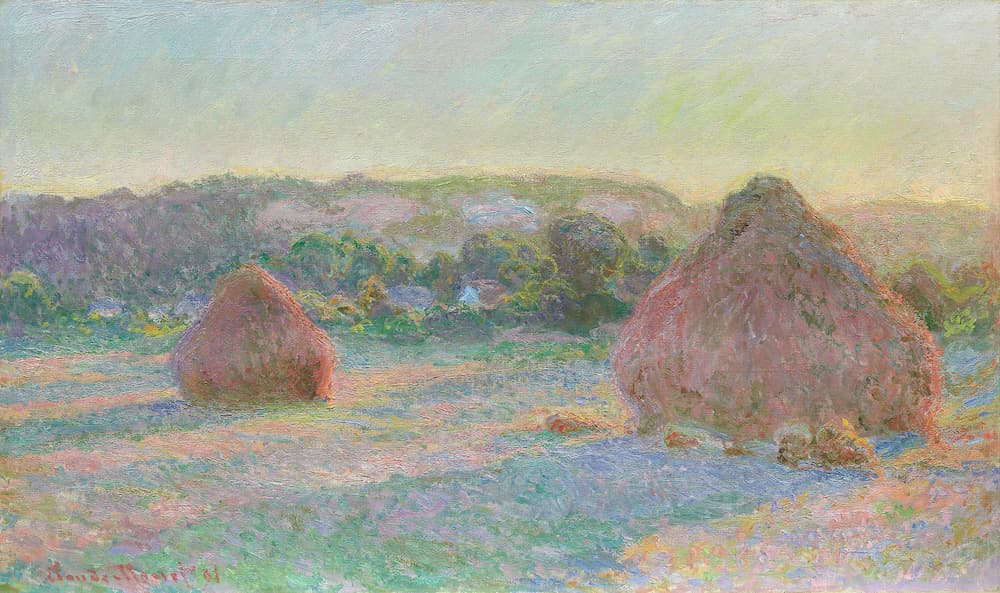

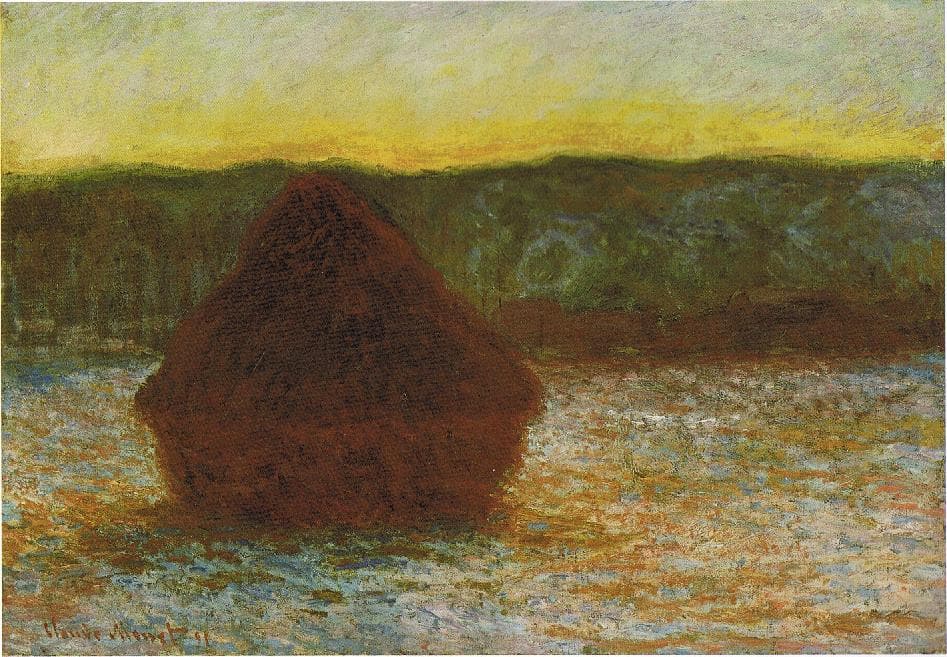

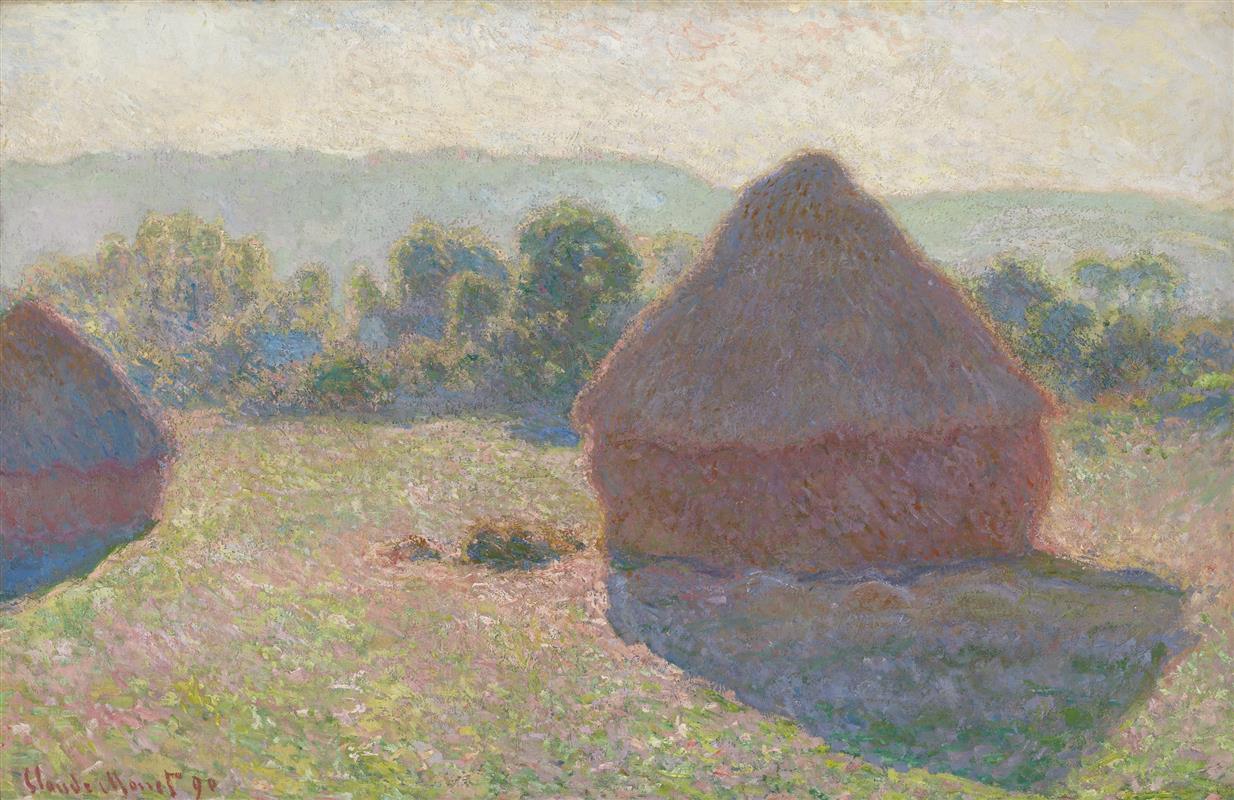

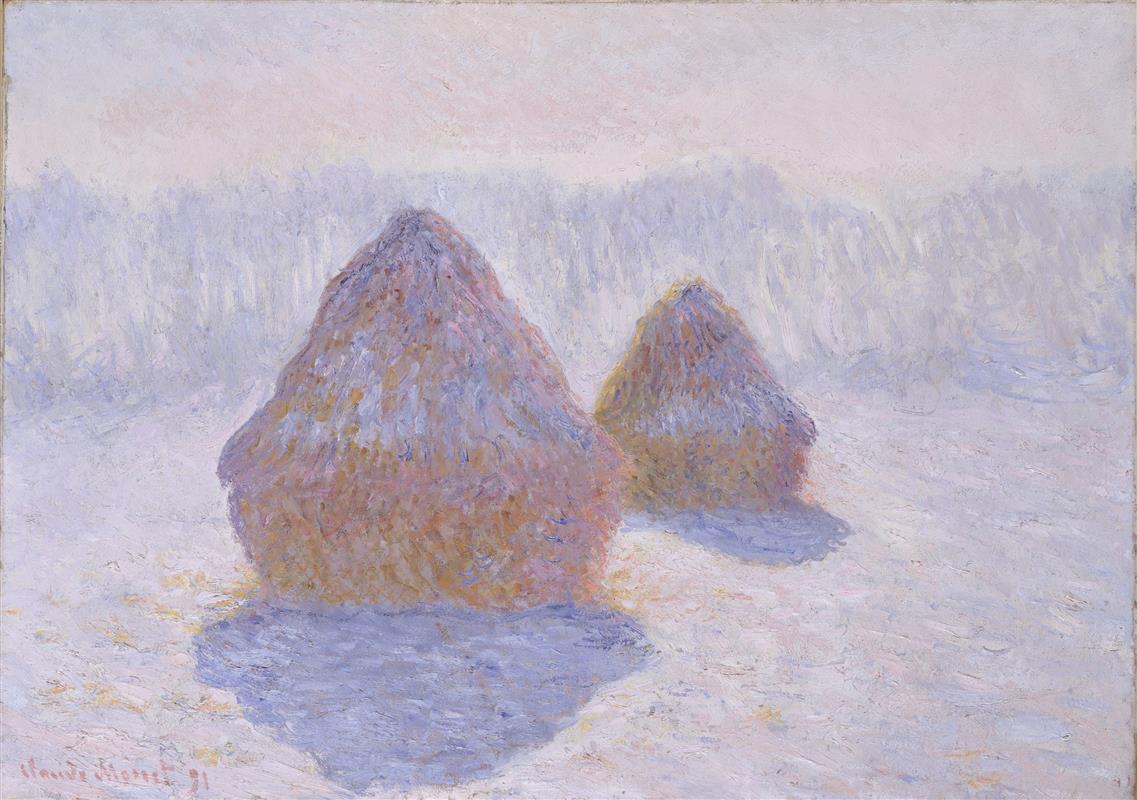

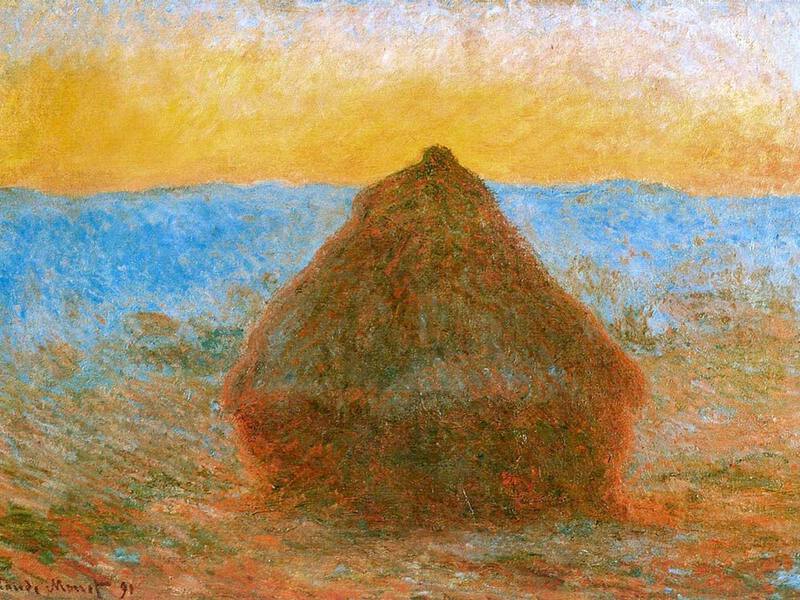

| Title | Wheatstacks (End of Summer) |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 60 x 100.5 cm (23.6 x 39.5 in) |

| Current location | Art Institute Chicago |

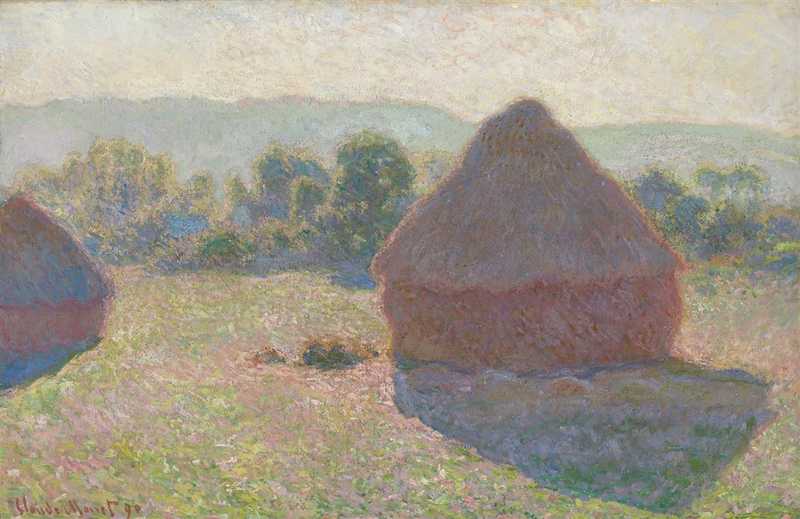

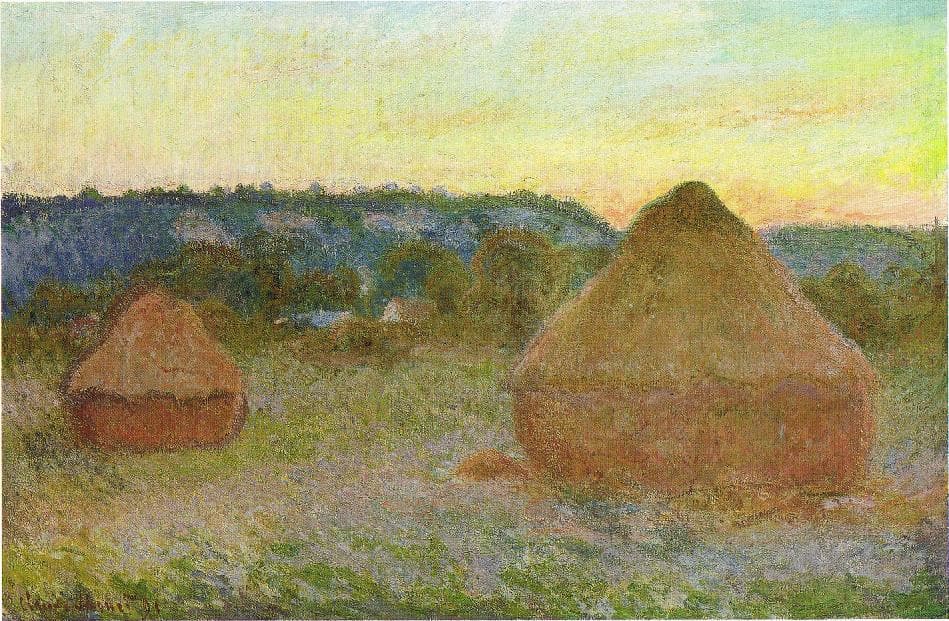

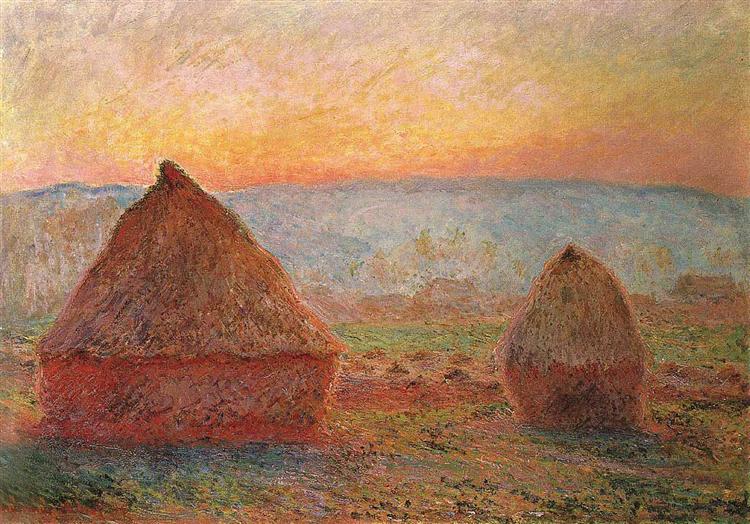

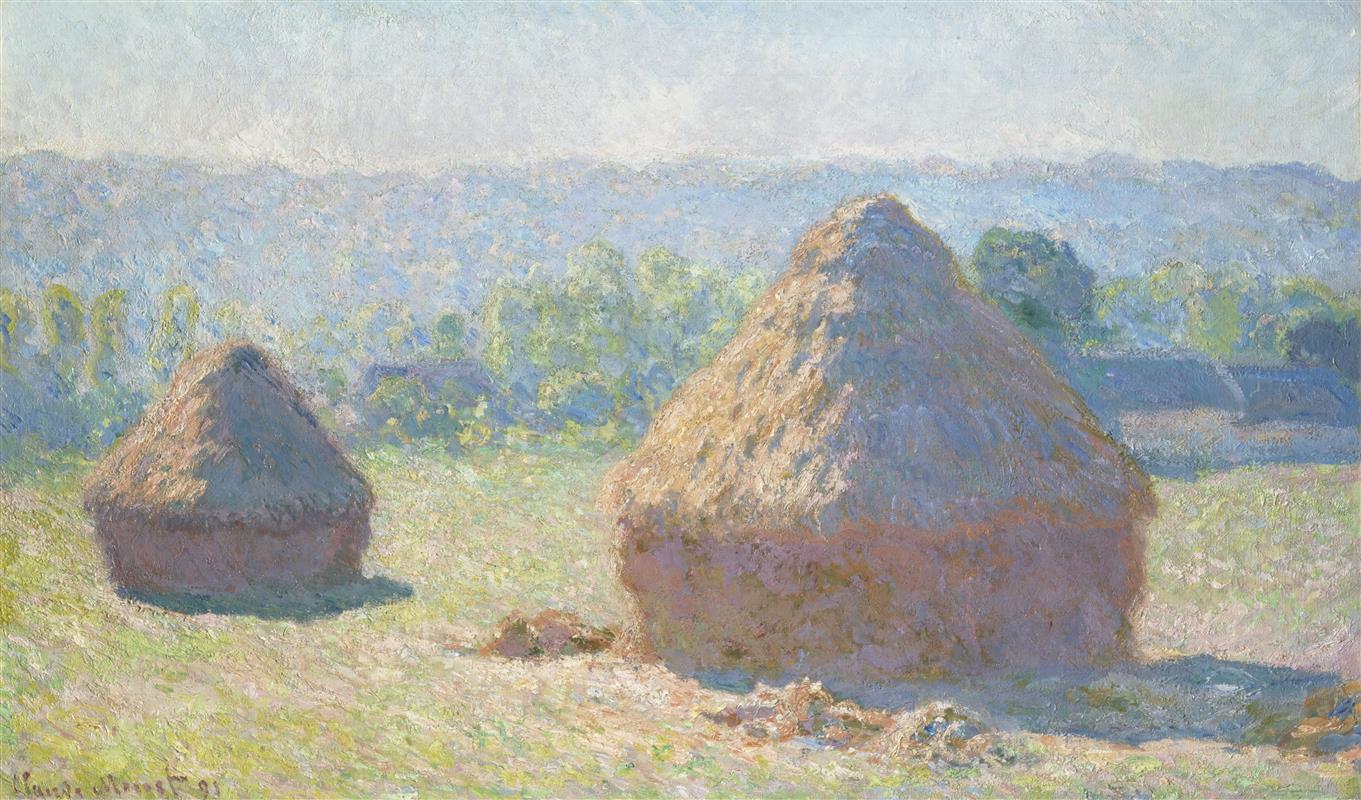

| Title | Wheatstacks |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 65.3 x 100.5 cm (25.7 x 39.5 in) |

| Current location | Art Institute Chicago |

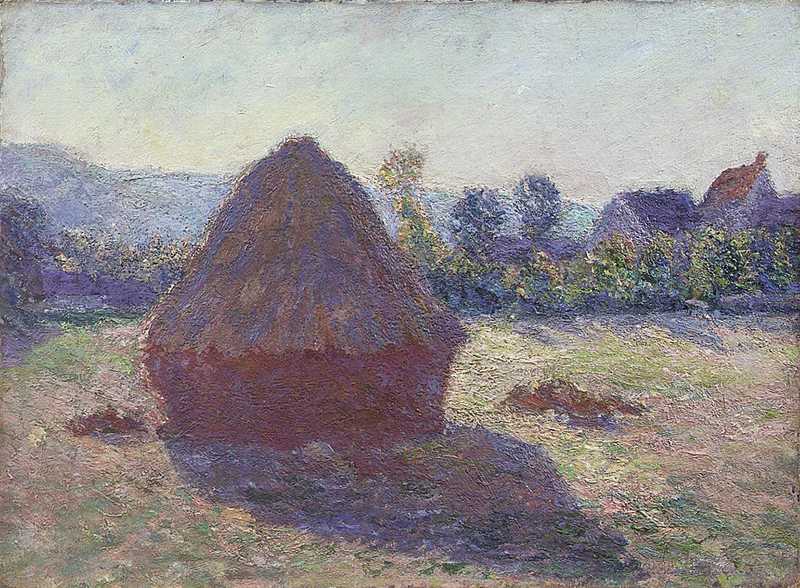

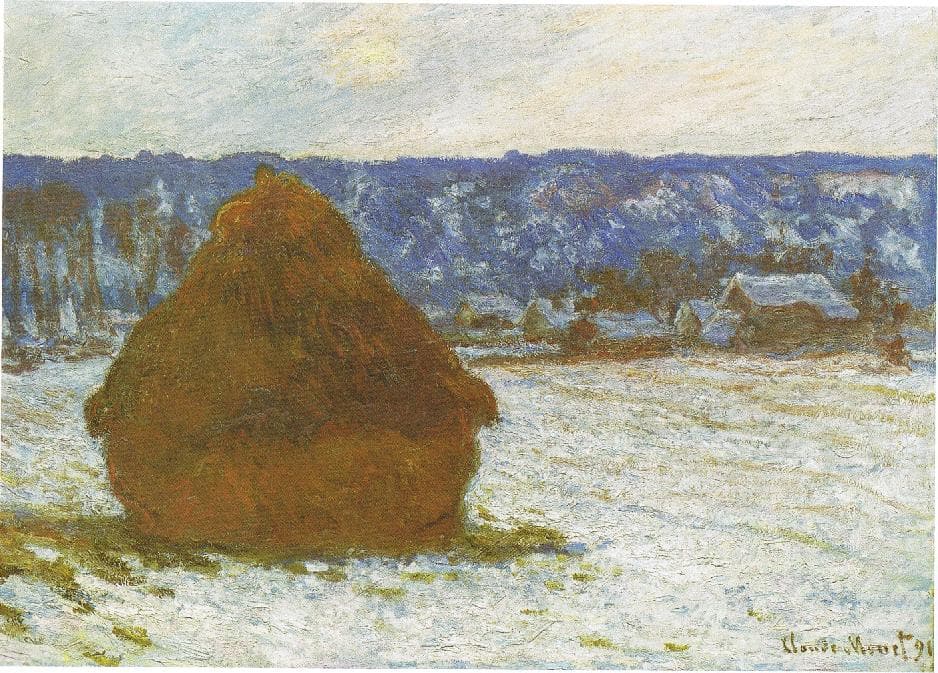

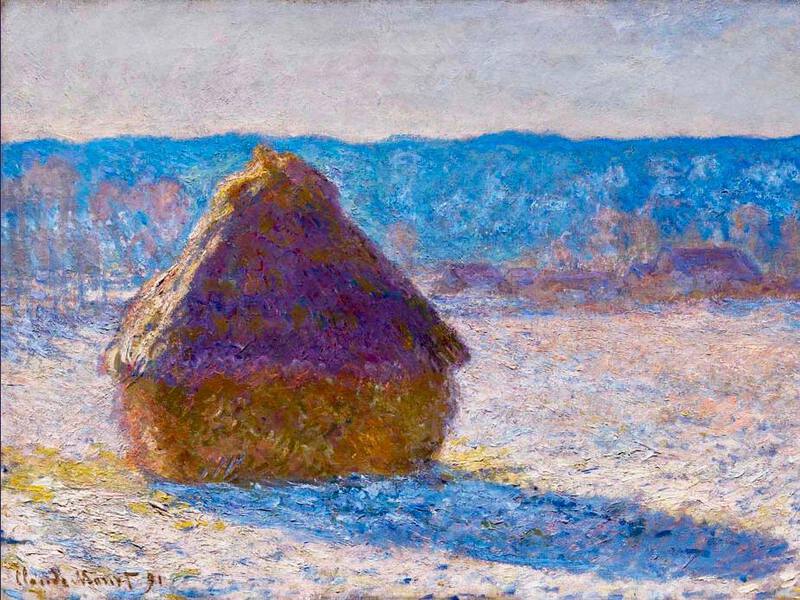

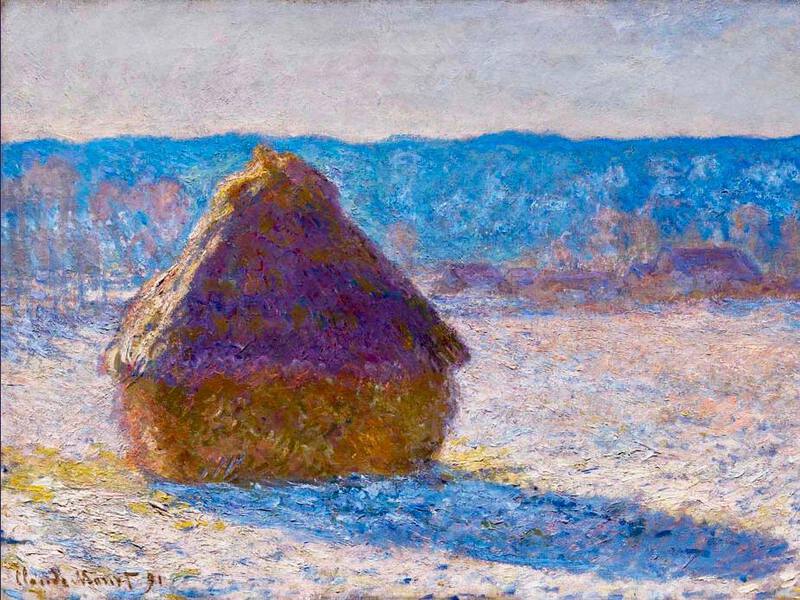

| Title | Wheatstack, Snow Effect, Overcast Day |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 66 x 93 cm (25.9 x 36.6 in) |

| Current location | Art Institute Chicago |

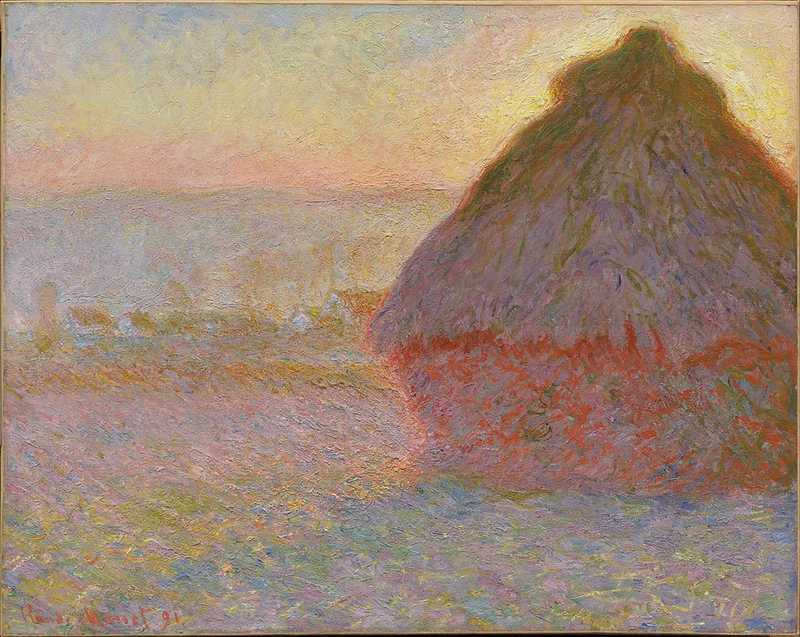

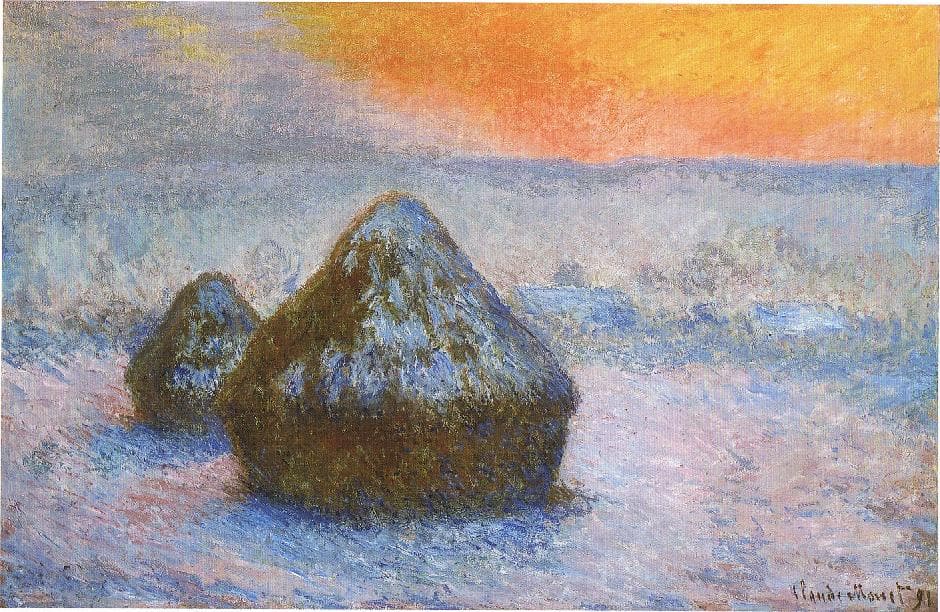

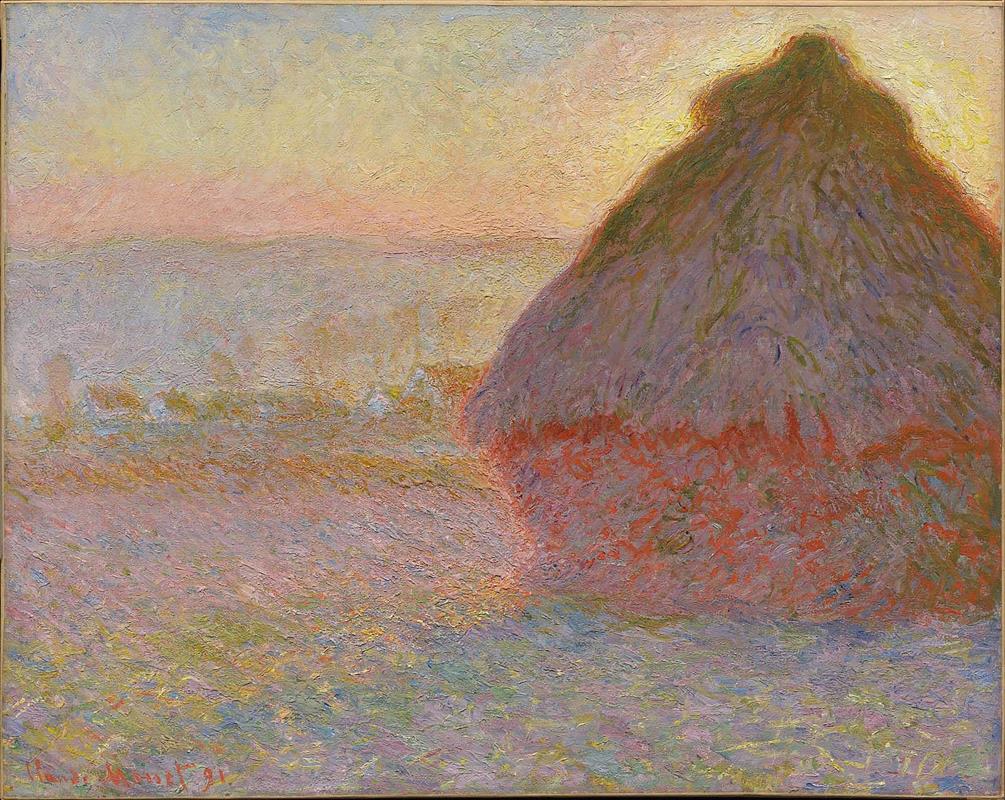

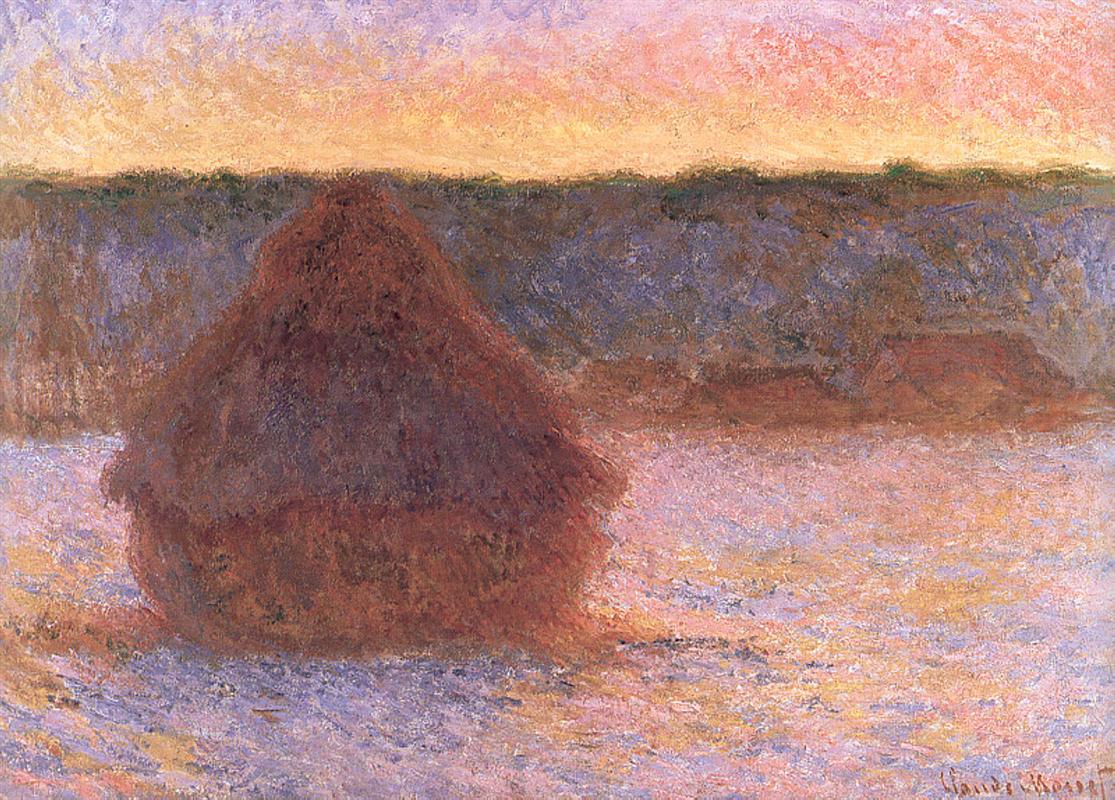

| Title | Wheatstacks, Sunset, Snow Effect |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 65.3 x 100.4 cm (25.7 x 39.5 in) |

| Current location | Art Institute Chicago |

| Title | Stack of wheat, Thaw, Sunset |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 64.4 x 92.5 cm (25.3 x 36.4 in) |

| Current location | Art Institute Chicago |

| Title | Grainstacks at Giverny, Sunset |

|---|---|

| Year | 1888 |

| Dimensions | 73.3 x 92.7 cm (28.8 x 36.5 in) |

| Current location | Art Institute Chicago |

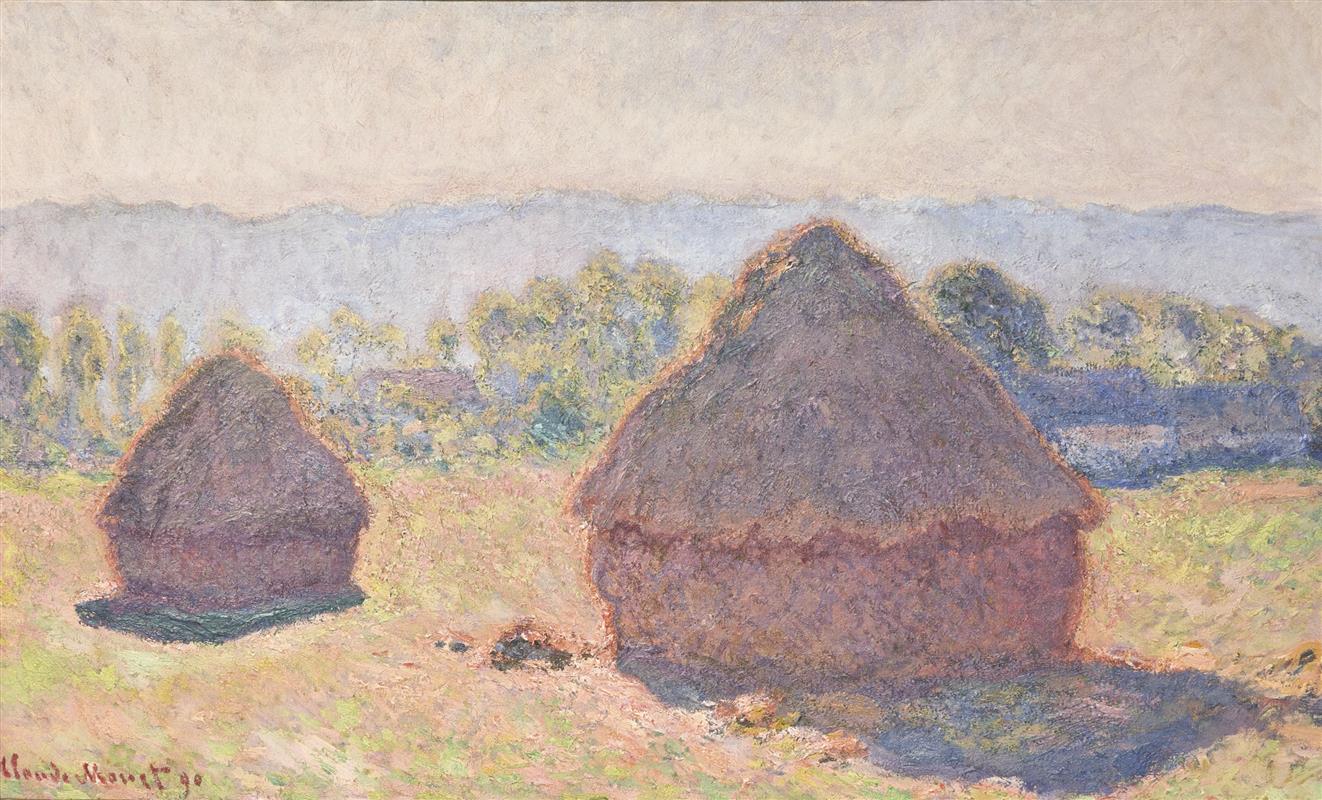

| Title | Grainstacks in Bright Sunlight |

|---|---|

| Year | 1890 |

| Dimensions | 58.4 x 96.5 cm (23 x 38 in) |

| Current location | Hill-Stead Museum |

| Title | Grainstacks, White Frost Effect |

|---|---|

| Year | 1889 |

| Dimensions | 58 x 71 cm (22.8 x 27.9 in) |

| Current location | Hill-Stead Museum |

| Title | Haystack, Morning Snow Effect |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 65.4 x 92.4 cm (25.7 x 36.3 in) |

| Current location | Museum of Fine Arts |

| Title | Grainstack, Sunset |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 73,3 x 92.7 cm (28.8 x 36.4 in) |

| Current location | Museum of Fine Arts |

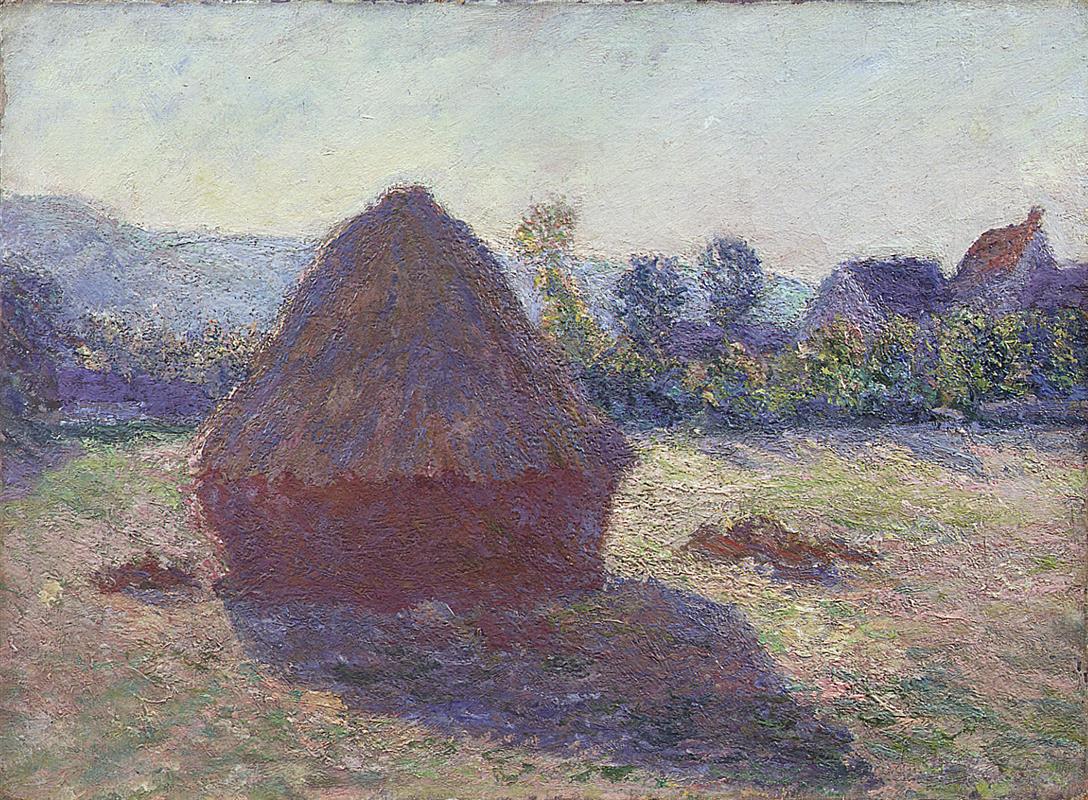

| Title | Grainstack at Giverny |

|---|---|

| Year | 1889 |

| Dimensions | 65 x 81 cm (25.5 x 31.8 in) |

| Current location | Tel Aviv Museum of Art |

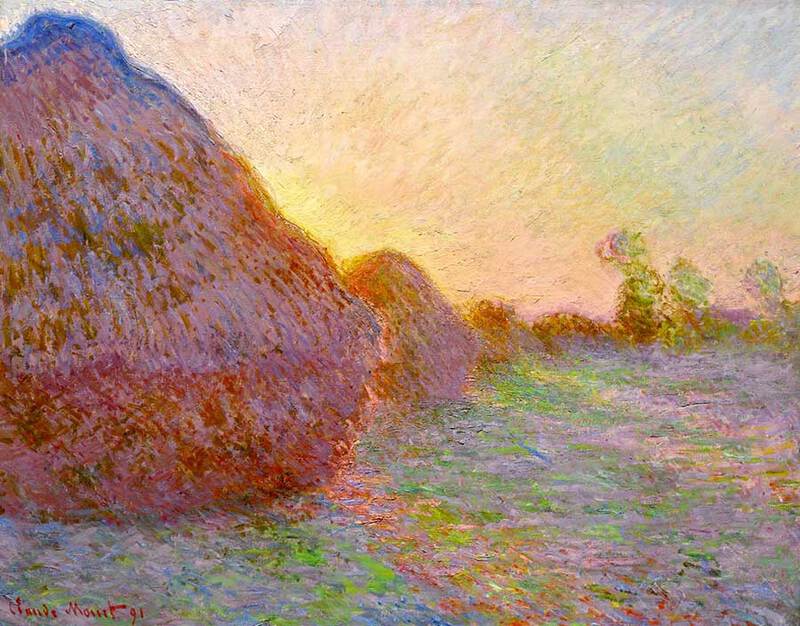

| Title | Stacks, End of Summer |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 60.5 x 100 cm (23.8 x 39.6 in) |

| Current location | Musée d’Orsay |

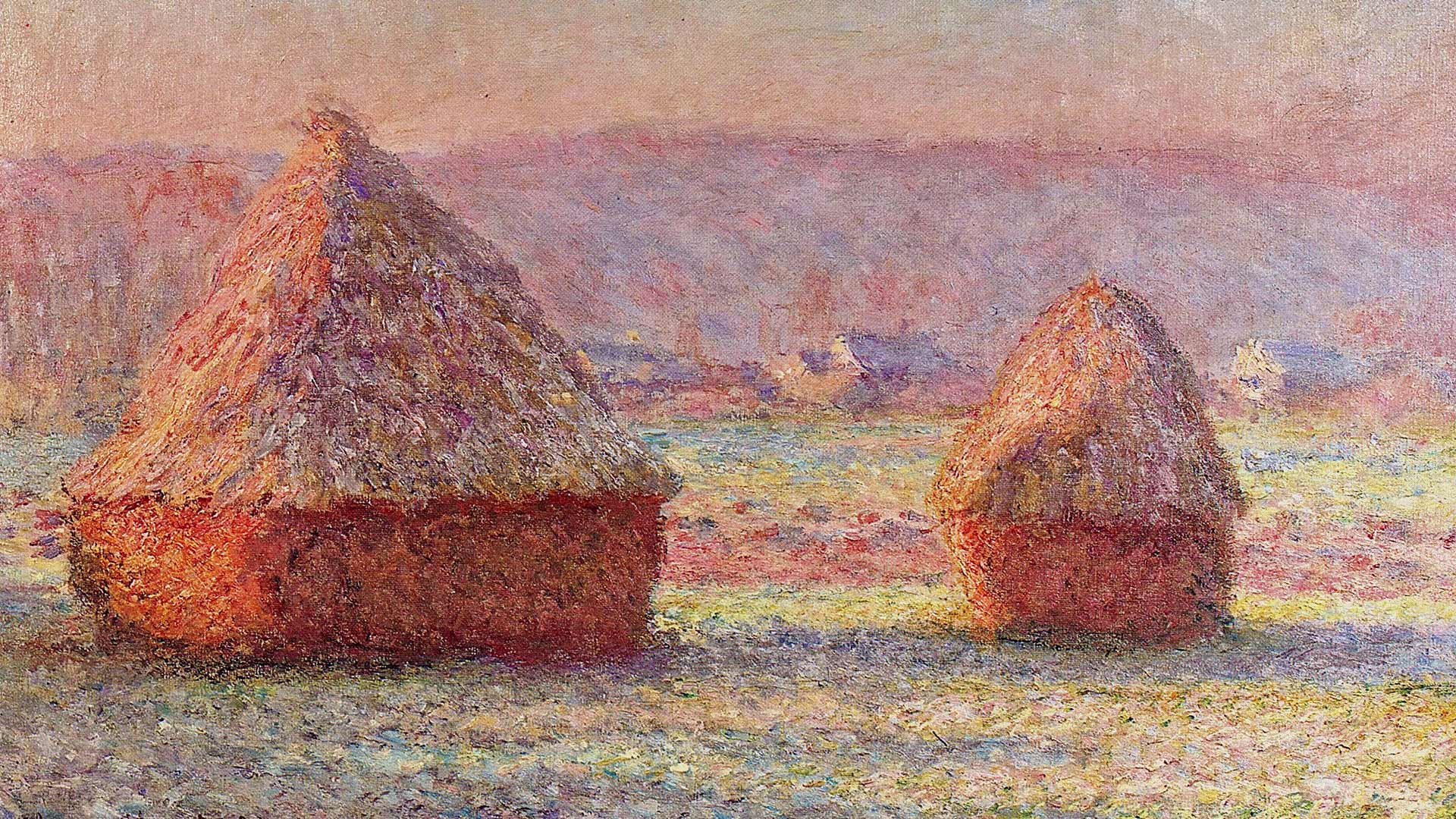

| Title | Grainstacks, White Frost |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 65 x 100 cm (25.5 x 39.3 in) |

| Current location | Shelburne Museum |

| Title | Haystacks (Midday) |

|---|---|

| Year | 1890 |

| Dimensions | 65.6 x 100.6 cm (25.8 x 36.6 in) |

| Current location | National Gallery of Australia |

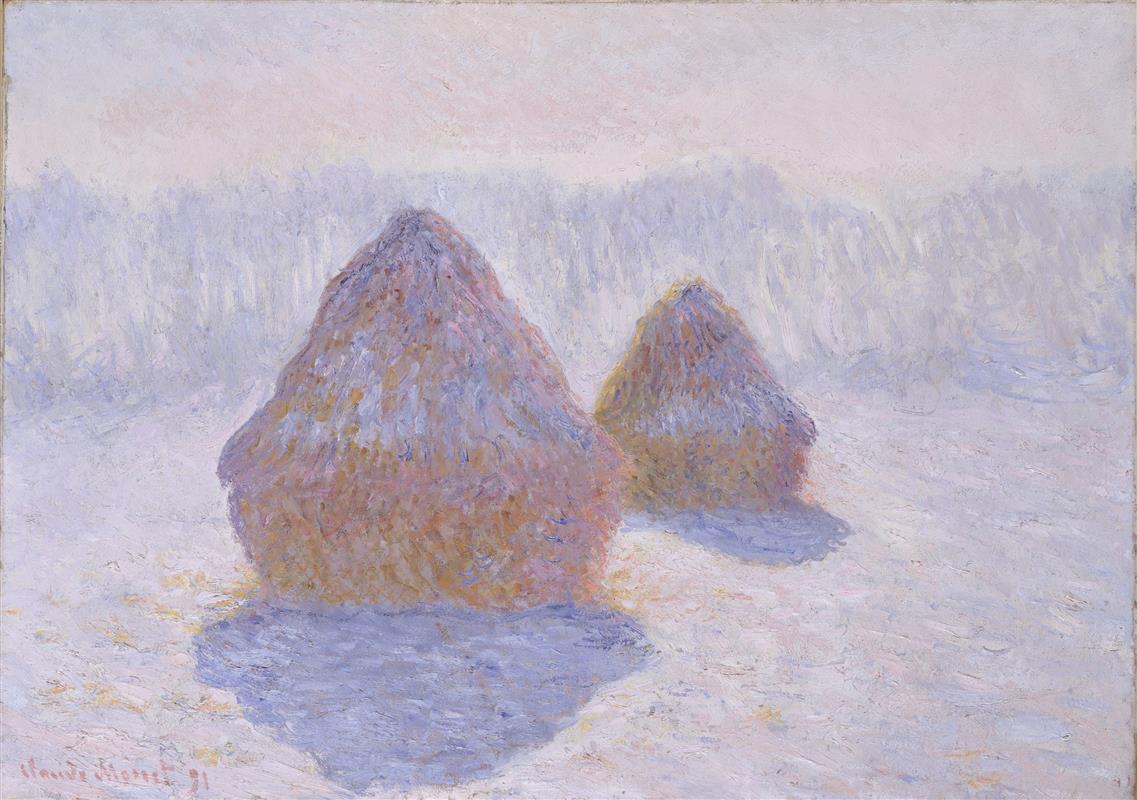

| Title | Wheatstacks, Snow Effect, Morning |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 64.8 x 100.3 cm (25.5 x 39.4 in) |

| Current location | J Paul Getty Museum |

| Title | Wheatstacks, Snow Effect |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 65 x 92 cm (25.5 x 36.2 in) |

| Current location | National Gallery of Scotland |

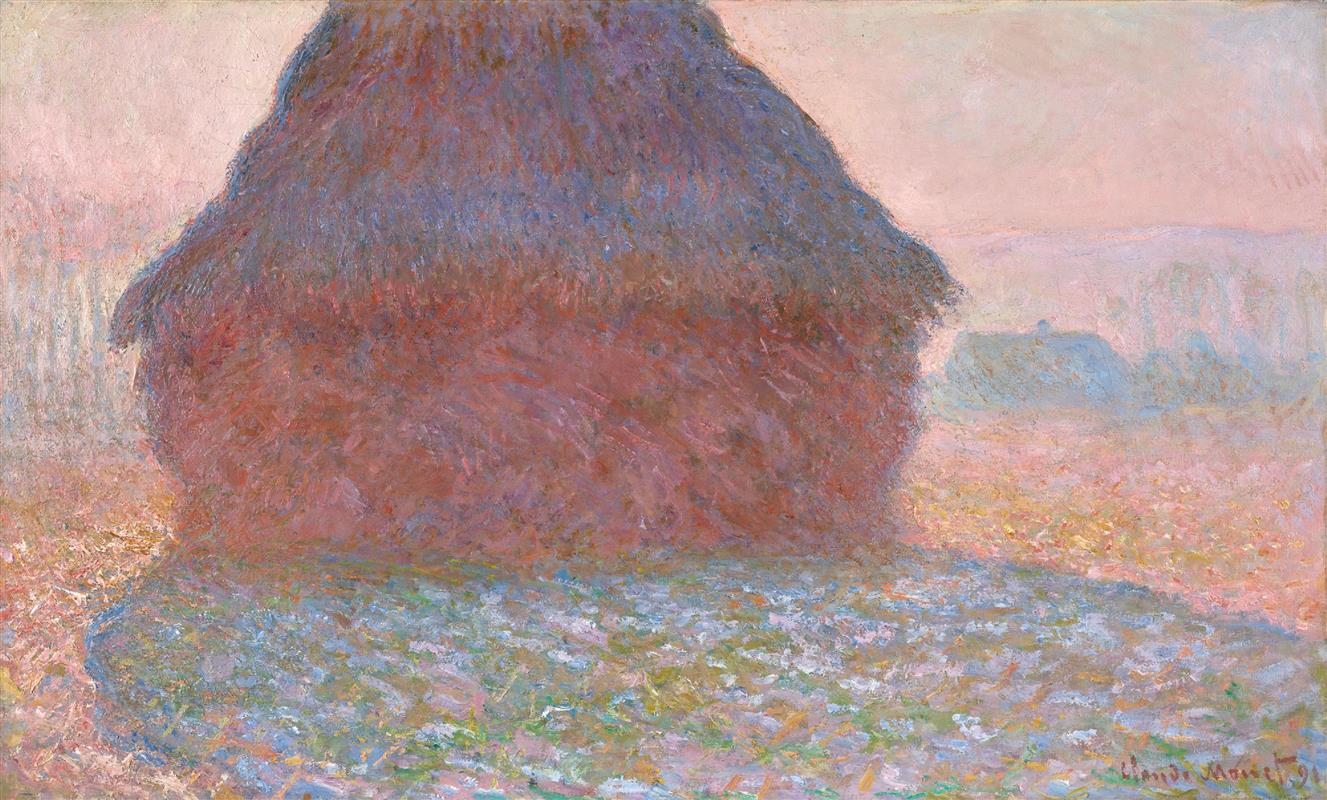

| Title | Wheatstack, Sun in Mist |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 65 x 100 cm (25.5 x 39.3 in) |

| Current location | Minneapolis Institute of Arts |

| Title | Haystacks, Effect of Snow and Sun |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 65.4 x 92.1 cm (25.7 x 36.3 in) |

| Current location | Metropolitan Museum of Art |

| Title | Grainstack in Sunshine |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 60 x 100 cm (23.6 x 39.3 in) |

| Current location | Kunsthaus Zürich |

| Title | Haystack in the Evening Sun |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 38.5 x 52 cm (15.1 x 20.4 in) |

| Current location | Gösta Serlachius Fine Arts Foundation |

| Title | Haystacks at Sunset Frosty Weather |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 65 x 92 cm (25.5 x 36.2 in) |

| Title | Grainstack |

|---|---|

| Year | 1891 |

| Dimensions | 65 x 92 cm (25.5 x 36.2 in)w |

2. ‘Haystacks’ 1888 – 1891

The ‘Haystacks’ series was constructed across two separate periods. The first five paintings were made during the harvest of 1888.

Some modern-day critics debate whether these early efforts should be counted as official members of the collection since they record hayricks rather than haystacks.

For example, the Hill-Stead Museum, Connecticut, holds two ‘Haystacks’ paintings; however, the gallery only refers to one as a “proper” member of the ‘Haystacks’ family because it dates from 1890, when Monet produced the second part of his series.

Regardless of the debate surrounding their history, ‘Haystacks’ are accredited for their atmospheric aesthetic that captures rural life during this period. In the late 1800s, it took time for threshing machines to travel from town to town. This allowed Monet to spend months inspecting the stacks: his exploits began at the start of Spring and concluded in the Autumn.

Monet watched as the seasons brought different challenges due to the spontaneity of the weather. Even in the icier months, his family recalled that he would awake at 3 o’clock in the morning and brave the cold in order to paint the scenery before any workers arrived. In fact, a portion of ‘Haystacks’ is dedicated to studies of ‘Frost’, ‘Mist’ and ‘Snow’. In these works, Monet uses wistful pastel colours to cast a simple sky, against which the stacks themselves appear vivid, bold and pointed.

Monet also spent many hours painting in the heat of the Summer sun. Using mottled dots of yellows, reds and purples, he crafted pictures of silhouetted stacks atop saturated backgrounds. In his daylit images, more details are available to the audience.

Monet uses two streaked techniques: the first is subtle, using overlapping pale colours to denote cloud cover; the second is more vigorous, employing diagonal lines to suggest strands of freshly winnowed wheat. Standing out from the daubed backdrop of trees and hills, the haystacks take their rightful pride of place as the main theme.

Although the assembly is known as ‘Haystacks’ in English, Monet’s paintings are actually more likely to depict sheaves of barley, oats or grain, which would have been transformed into food products during the time period.

3. What was Monet doing when he painted the ‘Haystacks’ series?

Beginning in 1888 and concluding in 1991, Monet’s series let him spend quality time in Normandy with his family.

The cosiness that Monet found in Giverny is transferred into the warm tones of ‘Haystacks’. Further, the shape of the grainstacks themselves with their roof-like caps mimic that of a European house. However, there was a regional reason as to why they had this form: the peaked contours meant that rain ran off easier.

The meadow in which the stacks stood belonged to Monet’s neighbour, whom he referred to as “Monsieur Quéruel”. Quéruel’s pastures were only a short walk from Monet’s home, so he could stop by often to observe or make sketches.

Though the ‘Haystacks’ are now a cherished part of Monet’s oeuvre, during the nineteenth-century Monet faced some backlash for his chosen motif. Conventions of the time criticised his pastoral imitations as being unexciting. Nevertheless, Monet’s Impressionist colleagues supported his choice as they were aware that he always cherry-picked his topic with care.

Fellow painter Camille Pissarro was especially vocal in his support of ‘Haystacks’, commenting:

“These canvases breathe contentment.”

4. Sunshine and Shadow

Among Monet’s works, these paintings in particular are an exploration of light and shadow, and the contrast between them.

Viewing Monet’s artwork with the seasons in mind, the transition between colour schemes is seamless. But the paintings hold more secrets. At the foot of each haystack, the spectator has hints to help them guess the hour in which the site was painted: the direction of the shadow is the clue.

As with most of his masterpieces, for the ‘Haystacks’ series Monet laboured outside painting ‘en-plein-air’. Due to the unpredictability of the elements, Monet switched between canvases onsite as the natural lighting changed. It was said that he worked on up to 12 canvases at once.

Monet asked his stepdaughter, Blanche Hoschedé, to be his assistant and she willingly agreed. Blanche used a wheelbarrow to transport his frames and supplies to and from the pasture. Many of Monet’s paintings were taken back to his then studio, a converted barn, where he would evaluate and edit them.

This fusion of staying true to observation and embellishing features in hindsight gave the canvases both a naturalistic and fictitious appearance; the design is realistic but some of the colours are curious. Monet mixes his palette and adds stippled purples, whites and greens in areas where they would not usually belong. As a result, the paintings carry a distinctive hue characteristic of Monet. This technique makes the light itself seem luminous, bouncing off the painting and into the eyes of the onlooker.

In Monet’s own words, he describes the complexity of dealing with ever-altering conditions: “For me a landscape hardly exists at all as a landscape, because its appearance is constantly changing; but it lives by virtue of its surroundings, the air and the light which vary continually.”

5. What is the current value of Claude Monet’s ‘Haystacks’ series?

During the 1890s, Monet was already an accomplished artist. His status meant that his work had the ability to pull in interest from across the ocean.

When art collector and avid promoter of the Impressionists, Georges Petit, showcased the first 10 of Monet’s ‘Haystacks’ paintings at Galerie Georges Petit, they gathered a lot of intrigue from North America.

Furthering this, the acclaimed art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel showcased the full serialisation in the year of their completion, 1891. Within a month, almost the full set had been sold to clients in the United States. The majority of the pieces were purchased for 1000 Francs. This financial win meant that Monet was able to buy his beloved house in Giverny outright, where he was staying when ‘Haystacks’ was created.

Today, paintings by Monet have monopolised the market for Impressionism: his most expensive piece to date is part of the ‘Haystacks’ series. In 2019 ‘Grainstacks’ (1890) became part of the Hasso Plattner collection, selling for $110.7 million. The painting is on loan to galleries globally and presently on display at the Museum Barberini.

6. Changing perspectives on ‘Haystacks’?

‘Haystacks’ has had an undeniable impact, presenting a meticulous example of how to capture changingconditions from a solo subject matter.

Additionally, it was the first time that Monet had experimented with a series of this kind. An experiment that would lead onto other sequential artworks such as his ‘Waterlilies’series.

This series was also monumental for future movements to come, going on to inform the work of artists like Pablo Picasso and the Cubists. Picasso became renowned for formulating ‘arcs’ of artwork: a good example is his ‘Blue Period’, spanning from 1901 to 1904, whereby he homed in on one shade for three years.

The scholar, Daniel Wildenstein, holds Monet’s ‘Haystacks’ in such high regard that they occupy their own codes, 1266 to 1290, within his Wildenstein Index. These catalogues, generated in the 1960s, are considered so imperative to the art movement that contemporary creative institutions and universities still use the system to this day.

Last of all, Monet’s ‘Haystacks’ capture a scene that would disappear during the 1900s. With the implementation of modernised farming technology, the turn of the century introduced the combine harvester to Europe. With mechanised equipment at their disposal, smallholders had less need for manual labour. Alas, Monet’s depictions of beautifully piled stacks of grain are now a glimpse of a bygone era. But perhaps that is best? After all, Impressionism champions life’s short-lived, candid and humble moments.