1. The painting

Manet depicts a riotous scene in the Masked Ball.

The scene

There are 23 top-hatted gentlemen, five women wearing masks, two unmasked women, a clown, and the dangling feet of an entertainer or showgirl.

This requires a little unpacking. The Masked Ball depicts a high society party at the Paris Opera House. The well-dressed men are plucked from Paris' social elite, attending a party to pick-up women.

The masked women are probably from the higher social classes, hiding their features to protect their reputations. And the unmasked women are almost certainly courtesans from the Parisian demimonde.

The motif is cropped so as to cut off half of the clown's body (left) and all but the dangling legs of an entertainer (top middle). Structure is provided by the balcony, and Manet draws the viewer in by using lots of black - one of his favourite colours - which is contrasted with white, orange, blue and gold.

Interesting fact...

The Paris Opera House burned down before Manet had finished his painting. Six thousand costumes, all the instruments and scores, and sets for 15 different operas perished.

The foreground

In the foreground, to the left, an unmasked woman in a multicoloured frock and white shirt croons at a nearby gentleman. With his hand tentatively touching her arm, it appears that they are about to dance. From their proximity, it could be suggested that the two are lovers but it is more likely that the scene is depicting prostitution, a common theme in many impressionist works.

In every section of the image, Manet has painted details for the viewer to admire. For example, the right foreground shows a masked woman carrying a beautifully painted bouquet and an orange!

Portraits within a painting

Manet depicted many of his friends in the scene, for example Emmanuel Chabrier (a young art collector).

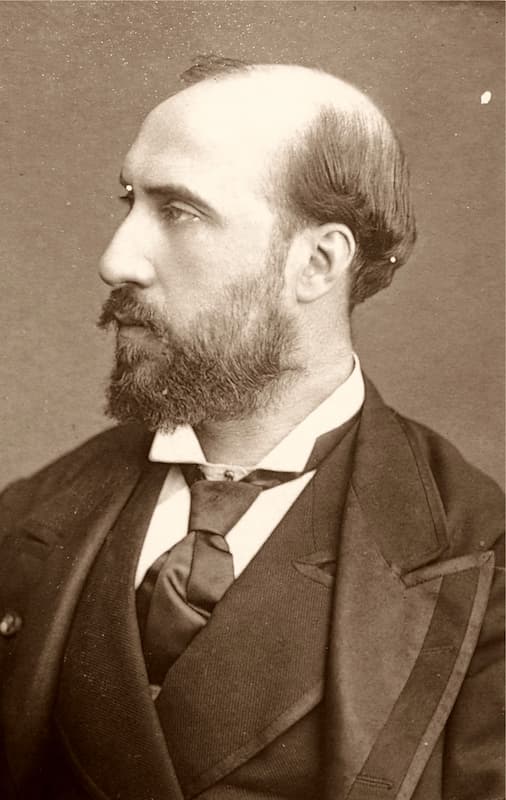

Manet also includes a self-portrait - see the second man from the right, sporting a rather impressive handlebar moustache. At his feet is a fallen dance card, on which Manet’s signature is confirmed.

This technique was borrowed from Classical practitioners, including those of the Renaissance, who often painted themselves into their own works.

Those dangling legs ...

Similarly, some of the hidden intricacies extend beyond the picture itself. On the upper floor, cinnabar-coloured boots dangle over the golden railings.

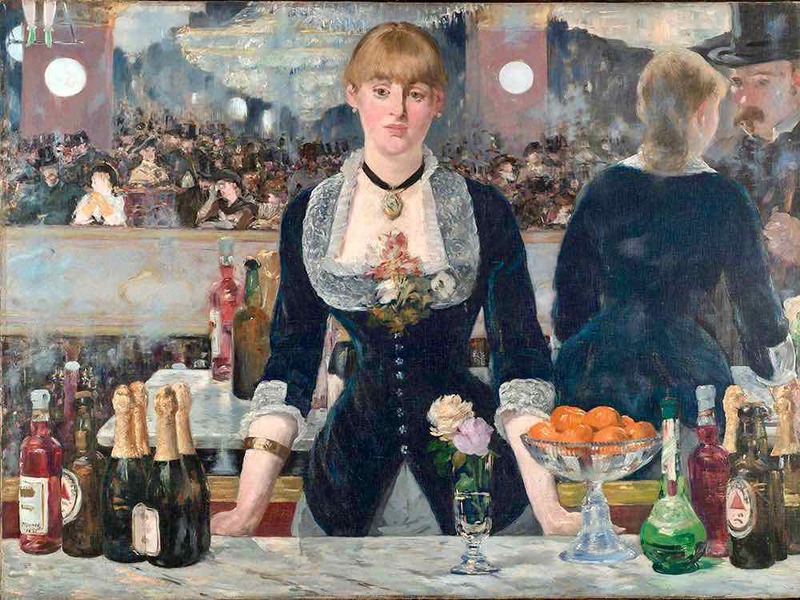

This pair of feet adds a hint of humour to an otherwise formal scenario. Manet incorporated this same detail in his later painting ‘A Bar at the Folies-Bergère’, 1882, whereby the shoes of a trapeze artist perform in the top-left corner.

2. Manet in 1873

While creating preliminary illustrations for the final piece, Manet decided to move studios.

Fire

Only a few months later, his previous workshop, at rue Le Peletier, was burnt to the ground. Had Manet not relocated to rue d’Amsterdam, his research for ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ would have been lost forever.

Preparation

Although the painting was finished in the spring, Manet’s sketches had taken months to amass. His design for the painting meant that several models were required, each of them posing for hours as he sketched their forms. Due to the time it took to create the primary plans, Manet was able to choose his subjects carefully.

Indeed, Manet produced a different - lesser known - version of Masked Ball at the Opera, shown below.

This version shows people crushing to get into what must have been a much-anticipated social event. The brush strokes are far coarser, but Manet captures the hustle and bustle perfectly. Note, in particular, the amount of bare flesh that Manet paints in the foreground. This version of the painting is found in Tokyo's Artizon Museum.

Manet's Circle

The Impressionists were well-known for their socialising. During the 1870s, Manet rubbed shoulders with many influential people of the decade.

By forming secret societies, gathering at cafés - like Cafe Guerbois, a favourite hangout - and joining political movements, the creatives of Paris played a significant role in the culture of the city.

In ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’, Manet adds his friends to the revelry, including the art collector, Albert Hecht, and the composer, Emmanuel Chabrier, to applaud France’s leading intellectuals of the age.

This mingling of philosophical souls was vital to this period. The loss of pride caused by their humiliating defeat in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian war haunted the French. Indeed impressionist artist Frederic Bazille died in the conflict.

It was only through these artistic gatherings that creators could lick their wounds and rebuild a better society. In these circles, Manet zealously investigated the positives and negatives of European society, both ridiculing and rejoicing in the uniqueness of his homeland.

3. Value

When considering Manet’s most expensive artworks, ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ appears high on the list.

Originally bought by his lifelong supporter, Jean-Baptiste Faure, the painting has seen a handful of owners through its lifetime.

As an opera singer himself, the venue would have been known to Faure. He already owned a large number of Manet’s works, and kept ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ until the age of 67.

Passed down the line, the most recent independent owners of ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ were the Havemeyer family, who then gifted it to Washington's National Gallery of Art in 1982.

Since the turn of the century, the painting has escalated in terms of status. An estimate from 2014 priced Manet’s masterpiece at a staggering $65.1 million. This is an unbelievable feat for a canvas once viewed with contempt by the critics and the Parisian elite.

4. The appeal of the Opera

Manet had a profound relationship to music.

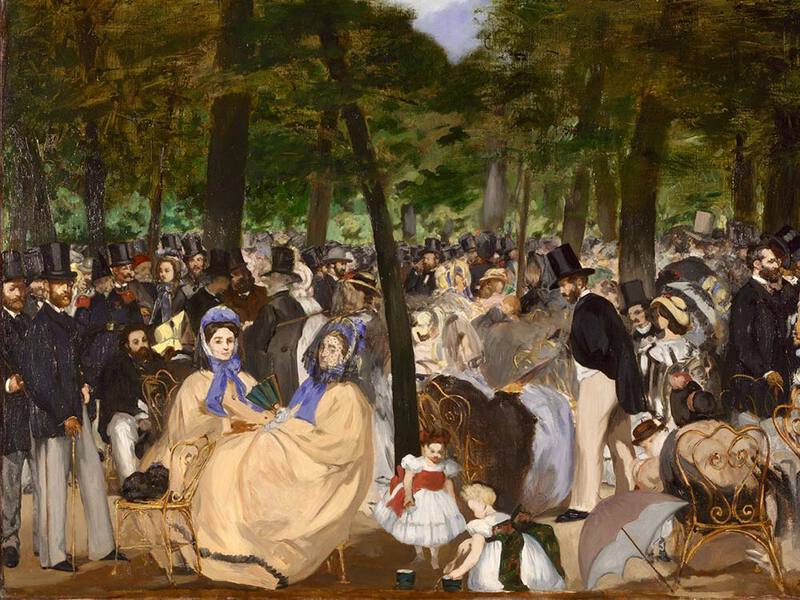

Many of his studies take place in theatre venues, their atmospheres so animated that the canvases carry a sense of sound. A piece which particularly stands out is Manet’s ‘Music in the Tuileries’ from 1863. Similar in style and composition to ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’, the pair project Manet’s excitement at seeing people enjoy entertainment.

Born into a prosperous family, Manet attained a taste for the finer things in life from a young age. As an adolescent, his fascination with leisure increased. Thus, he spent his career tracking the various activities rich Parisians had adopted as pastimes. In doing so, Manet was a slightly unusual case within the Impressionist movement, favouring indoor, urban spaces over ‘plein-air’ countryside views.

Manet frequently visited the wide range of events that Paris had to offer. As a Roman Catholic country, France held socials every year during Lent and one such event is illustrated in ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’. The topic of amusement was a welcome change to some within the Arts: poet and critic, Stéphane Mallarmé, said that Manet’s work was

“a break from the several tonnes of fresh bouquets [offered by other painters]".

With the arrival of the Impressionists, the transfer from Still Life to show business had begun.

Manet the trend setter

In fact, Manet was not the only artist of his era to be captivated by the theatre. It was also a much-loved setting for Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt as well, who owe some of their most profound pieces to Parisian playhouses and concert halls.

The Realist painter, Henri Gervex, was so gripped by the allure of live music that he created his own painting called ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ in 1886.

5. Changing perspectives on ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’?

A scandalous sight in its day, ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ still maintains a suggestive undertone in the twenty-first century.

Using colour, tone and light, Manet enhances the headiness of the scene. With the advantage of knowing the history of the piece, the true and seedy intentions of opera house festivities are crystal clear to a contemporary observer.

It is a mark of Manet’s presence as a prominent Impressionist that he was able to effortlessly challenge the establishment. Fear broke out when his painting was unveiled, as members of the Salon worried they would be identified, especially since their courtesans were present in the piece.

Just the year before, the Salon had affectionately displayed Manet’s iconic ‘Le Bon Bock’ at their exposition; a year later ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ suffered the opposite, being banned from their annual showcase in 1884.

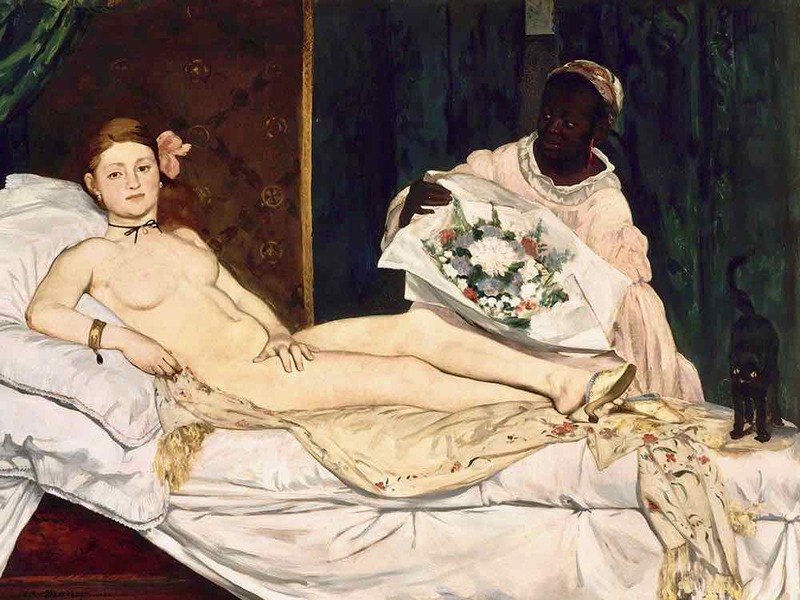

The story doesn’t stop there. Manet’s work has become the object of modern outrages too. In 2016, Luxembourgish performance artist, Deborah de Robertis, lay nude in front of Manet’s ‘Olympia’ at the ‘Splendour and Misery: Images of Prostitution 1850-1910’ exhibition, Musée d'Orsay. Following complaints, she was removed by the gallery’s guards.

Manet’s battle with delicate and taboo topics has travelled through time. From defying the conventions of academic painting to his risqué subject matter, Manet trialled multiple outlets to confront tradition. To add insult to injury, in ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’, he paints a literal clown to imply how childish the creative circles he moved in could be.

If it were not for the courage of artists like Manet, the new wave of creators to come may not have been so confident moving forward with controversial themes. Manet’s canvases of crowded places were also crucial reference points for younger Impressionists, such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Paul Cezanne.

All three would go on to create vast landscapes displaying large groups of people taking inspiration from Manet’s works.