1. Delacroix’s early years

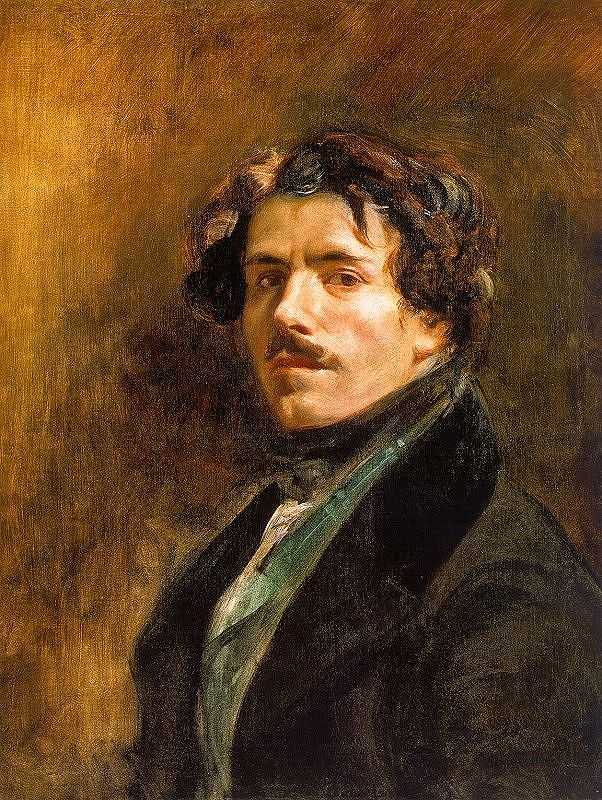

As a result of Delacroix’s prominent position in art history, there has been a great deal of academic study devoted to his early life and development.

Delacroix’s father

It is now suspected that Delacroix’s ‘father’ was in fact unable to bear children at the time of conception, as a result of the removal of a testicular tumour just seven months before Delacroix’s birth.

Charles-François Delacroix, his legal father, was in Holland at the time of his birth on April 26 in 1798. On the other hand, a close family friend and esteemed diplomat Maurice de Talleyrand was close by. As the young boy grew, his resemblance to Talleyrand and their similarity in temperament became more apparent.

Formative years

Young Delacroix, christened Ferdinand Eugène Victor Delacroix, grew up in the family of Charles-François Delacroix and Victoire Oeben. Charles was a foreign minister working in Napoleon’s regime but he was killed when Eugène was just seven. Shortly afterwards, his brother, Henri, was also killed in battle.

Delacroix was then raised by his mother, Victoire, who came from a family of artists. Her father was a well-known French cabinet-maker, Jean-François Oeben. Tragically, Victoire also passed away in 1814, leaving Delacroix an orphan at the age of 16. On his mother’s death, his care went to his older sister Henriette. She was married to a former ambassador to Turkey and so was able to give him a relatively stable home.

As well as the supervision of Henriette, Delacroix was also under the protection of Talleyrand who went on to become Minister of Foreign Affairs before serving the Restoration and King Louis-Philippe and then Ambassador of France in Great Britain.

Talleyrand stayed in close contract with Delacroix for his entire career. This ensured Delacroix’s safety through the tumultuous years of French politics, including the French Revolution, which began the year the Delacroix was born.

Early paintings

Delacroix’s early painting education was encouraged by his uncle, Victoire’s brother and artist Henri-François Riesener. He quickly became known for his artistic achievements at school at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris and the Lycée Pierre Corneille in Rouen. Next, Delacroix began studying in the studio of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin in 1815 before enrolling in the École des Beaux-Arts a year later.

The works produced during this period show indications of the painter Delacroix would become. He chose politically and emotionally charged subject matter, creating impressive and original compositions to highlight the drama of each scene.

British art

Another key aspect of the young student’s artistic education were his frequent visits to the Louvre in Paris. Here he would meet Richard Parkes Bonington and Raymond Soulier. These artists introduced him to new artistic influences from Britain and especially the alternative colour tones in British art.

It was through these connections that he also came to read British literature like Shakespeare, Lord Byron and Sir Walter Scott. Byron and Scott were important figures in the romantic movement in Britain and inspired Delacroix to recreate scenes from their works. He merged his classical training with observations from Rubens and Michelangelo, absorbing their love of drama into his own work and his illustrations.

The Barque of Dante

Delacroix’s first major painting, ‘The Barque of Dante’ was a culmination of these influences. It built on the works of Théodore Géricault and his piece ‘The Raft of Medusa’ in particular.

The painting was inspired by Dante Alighieri’s epic poem, the ‘Divine Comedy’, and the composition is extreme: Delacroix depicts the souls of the damned suffering in the water, hanging desperately and agonisingly onto the small wooden boat. This dramatic scene was greatly hailed by many when it was accepted into the Salon of 1822.

One critic said of the painting: “no work better reveals the future of a great painter”.

2. Delacroix and colour

Delacroix’s dynamic compositions and focus on dramatic scenes quickly earned him a reputation as one of the key figures in the romantic movement.

He began to associate with romantic painters and novelists, including Victor Hugo. His lifestyle suggests he enjoyed being in the company of brilliant, creative individuals, often becoming friends with the people who commissioned portraits from him.

This includes the novelist Georges Sand, who wished to be painted wearing men’s clothing for her portrait, as well as her lover Frédéric Chopin.

Colour theory

One of the key aspects of Delacroix’s artistic development was his adoption of colour theory and the laws of simultaneous contrast in particular.

He studied the work of Michel Eugène Chevreul, a chemist and author of ‘The Laws of Contrast of Colour’, published in 1839. This book was a best-seller, written for use by artists and designers of all types. Delacroix used the book as a manual for creating his own style of art, studying the text carefully to understand how he could implement colour theory in his paintings.

In doing so, Delacroix came to understand the principles of the division of tones, the harmony of contrasts, and more. He developed a technique for creating intense colour in his works known as ‘flochetage’.

Flochetage built directly on Chevreul’s colour theory using small flecks of colour to create an optical mixture. By honing these techniques, Delacroix was able to make his colours appear brighter and more intense, adding to the energy of his canvasses.

Flochetage

Through this stylistic development, Delacroix left the work of Neo-Classicism firmly behind, focussing on colour effects rather than form and especially the clean, crisp outlines of the academic style.

This set him apart from many of his contemporaries, including Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, with who he had a strong rivalry for much of his career. One of the best known examples of Delacroix’s flochetage technique is ‘Ovid Among the Scythians’ from 1859.

Delacroix was one of the first artists to develop this technique and he experimented with weaving together ever more complex patterns of paint and tiny brushstrokes. Delacroix’s innovations were one of the central influences on the Post-Impressionist Pointillist movement and its figurehead Georges Seurat.

Seurat studied Delacroix’s method closely along with the writings of Chevreul, pushing the technique even further to create the Pointillist aesthetic. This highly scientific and methodical style of painting applied contrasting colours in precise spots or points of paint to create an optical mixture, leaving behind the fleeting nature of Impressionist painting that had come before.

Women of Algiers in their Apartment

There are countless examples of Delacroix’s use of colour but perhaps one of the most influential was ‘Women of Algiers in their Apartment’ from 1834.

This painting depicts three women seated on the floor and was directly inspired by Delacroix’s journey to Morocco in 1832, which greatly influenced many of his artworks. As well as the exoticised subjects in patterned clothing, the setting is colourful and in keeping with an orientalised aestehtic.

The home itself is said to have been inspired from his visit to a Muslim man’s house in Algiers which had a separate apartment for the women of his household. However, in reality there would have been far more activity in the scene, including children. Delacroix dispensed with these figures in order to create a romanticised, luxurious image instead.

The colours in the painting are rich and intense, adding to the mystique of the painting and the women lounging in the scene. He carefully noted the different colours of the women’s clothing on his watercolour sketches.

This palette would go on to inspire artists such as Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse who drew on his sensuous portrayals of Orientalized female figures.

3. Delacroix and the Impressionists

Delacroix was a prominent source of inspiration for the impressionist movement.

He worked to manipulate light and colour in his works, drawing out the emotion of every scene. The Impressionists built on his concepts, adapting and shaping them to create their own artistic vocabulary.

The Death of Sardanapalus

He painted sensual subjects in a way that focussed on colour and luminosity to portray the drama of the pieces.

Many times, he caused outrage due to his subject matter, as in his 1828 work ‘The Death of Sardanapalus’, a writhing mess of bodies and torture inspired by Lord Byron’s play of the story and a favourite of the Romantics.

He did not shy away from his portrayals of human sexuality but also human suffering. The French monarchy found this work to be tasteless, echoing the later critiques of the Impressionist’s own nude paintings.

En Plein Air

Similarly, Delacroix began painting outdoors, depicting landscapes as he saw them in natural light rather than painting from memory in a studio. He believed that this was necessary in order for him to grasp the true colour of the object, which required sunlight to be visible.

Though it may seem normal now, Delacroix was one of very few artists doing so at this time. The Impressionists took this technique to the next level, dedicating themselves to painting outside ‘en plein air’ in order to capture ordinary life and nature in the most expressive way possible.

Homages to Delacroix

In many ways, the Impressionist’s relationship with Delacroix can be seen in their repeated references and replications of Delacroix’s work. Renoir was commissioned to paint ‘The Jewish Wedding in Morocco (after Delacroix)’ in 1875, reproducing Delacroix’s earlier painting from 1839 of the same name.

Renoir did so faithfully whilst also adding his own touches to the master’s work. His brushwork, use of light and his palette transform Delacroix’s artwork into a fully Impressionist piece. This work demonstrates not only Renoir’s abilities as a painter and an individualist but also how seamlessly many of Delacroix’s works could meld into the Impressionist style.

Similarly, Renoir’s ‘Study: Torso, effect of sun’ from 1875-76, which gathered the infamous criticism from Albert Wolff that “a woman’s torso is not a mass of decomposing flesh with the purplish-green splotches that denote the final stages of putrefaction in a corpse”, also echoes Delacroix.

His painting 'Female Academy Figure: Seated, Front View (Mademoiselle Rose)’ from 1820-23 features the same bluish tints and dapples that create the impression of pale flesh.

Delacroix played with colour mixing in rendering natural forms, including bodies. The Impressionists took these experiments further, adding ever more expressive brushstrokes to their compositions to enhance the colours. Cézanne best summarised the influence of Delacroix in the words, “we all paint in Delacroix’s language”.

Still Lifes

As well as exoticised and often erotic works, Delacroix also paved the way for the Impressionists to bring back flower pieces.

These still lifes had somewhat gone out of fashion at the time Delacroix was working in favour of grandiose history painting.

Undeterred, Delacroix dedicated much time to floral works in his later years. This was due in part to his failing health that caused him to make visits to his country home in Champrosay in order to escape the city.

In his still life works, Delacroix dispensed with the vases and drapes of earlier still life paintings, often choosing to depict his bouquets of flowers in natural settings.

At the same time, he focussed more on the overall effect than the individual, botanical detail of each flower, utilising colour harmonies to create an expressive scene.

This ‘impressionistic’ approach inspired the works of Claude Monet,Gustave Caillebotte and Vincent van Gogh among others.

4. Delacroix’s legacy

Towards the end of his life, Delacroix’s health suffered and he became very frail as a result of bronchial infections.

The diligent care of his housekeeper, Jeanne-Marie Le Guillou enabled him to keep working on larger projects, including commissions for murals like the Chapel of the Holy Angels in the Church of Saint-Sulpice from 1849–61. Le Guillou nursed him during his later years until he eventually died on August 13 1863 in Paris.

Delacroix is buried in Paris ’Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Significance

Delacroix’s influence on the impressionists was hugely significant from his approach to emotion and expression to his interest in natural light and his obsessive studies of colour.

He was an instrumental figure in the development of the movement. His use of tones and understanding of complimentary colours went on to inspire the work of Van Gogh,Monet,Camille Pissarro, Seurat and many more.

Furthermore, his role as a figurehead for colour experimentation continued into later movements with later artists such as Pablo Picasso taking inspiration from his works. Indeed, Picasso's painting ‘The Women of Algiers, after Delacroix’ from 1955 is a direct homage to his work of the same name, employing a similar colour palette but rendering the bodies as abstracted, cubist forms.

Liberty Leading the People

The most famous work from Delacroix’s career and arguably his most significant legacy is ’28 July: Liberty Leading the People’ from 1830, intended to be a way of honouring the brave revolutionaries from the French Revolution, which helped to establish the Second Republic.

The painting shows the unity of classes and it is thick with symbolism, painted in true Delacroix style with a strong focus on colour. The blue, white, red of the French flag is repeated throughout the composition with a female figure representing Liberty and the French Republic.

This image has etched the work of Delacroix onto the minds of many, whilst also serving as an exemplar of his extreme style.

Delacroix the chameleon

Throughout his life, Delacroix sought to portray human experience and the myth, history and exoticism within in the most extreme way possible. He selected subjects that showed wildness, agony and ferocity in a way that came to characterise the romantic movement.

On the other hand, he was also capable of creating tranquil, modest still life works that were far removed from his large-scale paintings in all but the colour palette.

In many ways, the avant-garde poet and critic Charles Baudelaire best summarised the work of Delacroix, his friend, immortalising his artistic legacy in the words:

“[he] was passionately in love with passion, and coldly determined to seek the means of expressing it in the most visible way.”

The passion that fed through all of Delacroix’s paintings and his innovative work with colour are his most important contributions to art history.