1. Seurat’s early years

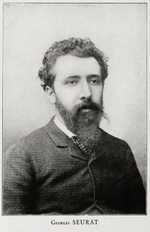

Born in 1859 to a middle-class Parisian family, Seurat’s congenial childhood allowed him to explore his interest in painting from an early age.

Seurat’s family

Seurat’s mother, Ernestine Faivre, came from a wealthy family of sculptors in Paris, known as the Veillards. Her father was a jeweller in the Rue de la Barillerie and her family’s comfortable life was passed on to her children, they did not have to worry about finding a profitable trade or starting apprenticeships.

Ernestine raised Georges and his brother and sister almost entirely on her own as their father spent much of his time outside the city. The children and their mother were very close. It was Ernestine’s brother, Paul Haumonté, who first began giving Georges informal painting lessons as he was an amateur painter himself.

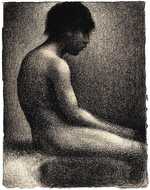

Black and white

A portrait of Ernestine is now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York titled ‘Embroidery; The Artist's Mother’ from 1882-83. The piece is sketched from Conté crayon, a later favourite of Seurat, and the image is constructed entirely from tonal passages of black. There are no lines to distinguish features within the drawing, instead the work is an inky abstract image that builds up the figure’s peaceful face and hands with masterful shading.

This drawing is characteristic of Seurat’s early interest and accomplishment in black and white drawings, which was a key area of focus at the beginning of his career. Similarly, this portrait is a fleeting sketch of a moment in time, another quality that was common to the artist’s early works. Seurat submitted this drawing to the Paris Salon in 1883 but it was rejected.

Eccentricity in the family

In contrast to his mother, Seurat’s father, Chrysostome-Antoine Seurat, was a highly unusual and eccentric man. He had accumulated great wealth through property speculation and retired from his job as a bailiff before Georges was born, following an accident in which he lost an arm. Since his retirement, he had lived almost permanently in a suburb outside of Paris called Le Rancy, returning once a week to briefly visit his wife and children in the city.

For much of Seurat’s childhood, his father lived the life of a hermit.

Seurat’s first studio

In spite of this, it was at the cottage in Le Rancy that Seurat first began to paint outdoors, and this was also the location of Seurat’s first studio. A number of small oil sketches from this time indicate his interest in country life and the everyday scenes in the suburbs surrounding Paris. ‘The Stone Breaker’ from 1882 is a slightly later work that demonstrates his interest in the labourers in Le Raincy. Critics have likened this focus on working-class people to the work of Gustave Courbet.

Another artistic influence inherited from his father was Seurat’s interest in simplifying images to provide them with greater monumentality. Art historians have linked Seurat’s paintings emphasising the figures as motifs to his father’s collections of religious images.

Chrysostome-Antoine had a large number of illustrated broadsheets, intended for popular consumption, which featured religious subjects from Épinal. As a child, Seurat would have had a chance to study these simple works and this may have formed the base of his inspiration.

Overall, the young student’s early artistic education was fairly traditional. He enrolled in a local art school around 1875 before moving to the École des Beaux-Arts, which was at this time run by Henri Lehmann. Lehmann was a student of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and as such, the teaching was firmly Neo-Classical, placing weight on drawing and composition.

This style of formal training set Seurat apart from many Impressionist artists as he had the opportunity to learn the techniques of Neo-Classicism. Generally, Seurat accepted the teaching he was given, as indicated in his early life drawings and copies of sculptures that were entirely in keeping with his art masters’ instructions.

However, he also conducted his own study in museums and libraries around Paris. It was his early discovery of Michel-Eugène Chevreul’s ‘The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colours’, which would be a key turning point in the development of Seurat’s artistic tastes and his wider career.

2. Seurat and the Impressionists

Together with his friends Ernest Laurent and Édmond-François Aman-Jean, with who he had first entered the École des Beaux-Arts, Seruat began renting a studio in Rue de l’Arbalete.

His career was briefly interrupted by a year of military service in Brest, during which time he filled his sketchbook with studies of the sea and ships.

The Fourth Impressionist Exhibition

In 1879, Seurat attended the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition where he had the opportunity to see works by artists such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. This was an important moment for him as he was confronted with a new form of artistic expression that shunned the academic rules enforced on artists at the time, including himself.

Like the Impressionists, Seurat was unsuccessful in his attempts to enter his work into the Paris Salon. He was rejected time and time again and was successful in having his work represented just once. This was in 1883, with a drawing of Aman-Jean. The Impressionists’ example of a school of artists set apart from the mainstream undoubtedly inspired Seurat to follow suit.

Points of distinction

Though he drew inspiration from the Impressionists, there was a number of areas where Seurat’s work diverged from the typical Impressionist style.

The Impressionist’s emphasis on modern subjects, depicting life in urban Paris and the surrounding countryside, interested Seurat. He adopted this approach in his works, sketching the scenes he saw around him.

Seurat also borrowed from the Impressionists in his bright colour palette. Like many Impressionist artists, he imitated the light found in nature in his canvasses, rendering his subjects in shimmering tones.

On the other hand, Seurat was uninspired by the Impressionist’s emphasis on capturing a fleeting moment. Instead, he favoured a more considered and scientific approach to depicting scenes from ordinary life, focussed on the essential aspects of life that change little over time.

Though Seurat’s works were shown at the eighth and final Impressionist Exhibition, they contrasted heavily with the Impressionist approach to painting, so much so that it was decided they should be hung in a separate room.

Félix Fénéon, a prominent art critic, was the first to name the paintings as Neo-Impressionist. From this point forwards, the work of Seurat and his followers became known as Neo-Impressionism.

3. Seurat and Neo-Impressionism

In defining the Neo-Impressionist school, Seurat successful merged the rigours of scientific colour theory with the poetry of the Impressionists. His innovative approach was largely driven by a fascination with scientific theories of colour and form.

Colour theory

Seurat sought to exploit the expressive effects of colours in his paintings, as well as experimenting with angled lines. This was where Chevreul’s writings were enormously influential, providing Seurat with a guide to manipulating colour to greatest effect by taking a studied, academic approach to colour theory. Seurat even had the opportunity to meet the famous chemist himself, who was by then 100 years old.

As well as the work of Chevreul, Seurat also spent time studying the theories set forth by Charles Blanc in the ‘Grammaire des arts du dessin’ or ‘Grammar of the Art of Drawing’. Blanc acknowledged the important work of Eugene Delacroix on expanding the use of colour theory in art. Delacroix was a key source of inspiration for the Impressionists thanks to his expressive, dynamic approach to painting and Seurat also studied his techniques.

Grammar of the Art of Drawing

Blanc believed that in the same way that music is decipherable, so too is colour.

Like Chevreul and Delacroix, he experimented with the theory of optical mixing, in which small brushstrokes of different colours are placed next to each other to increase the brilliance of the colours. This quasi-scientific approach to painting appealed to Seurat and he sought to build on their work. At the same time, he drew on the short, loose brushwork of the Impressionists to develop his technique.

Pointillism (or Divisionism)

Over time, Seurat created what he called ‘Chromo-luminism’. This is now better known as Divisionism and Pointillism. Divisionism was a method in which Seurat separated blocks of colour into distinct dots of paint to build up forms and figures in his artworks. Pointillism was the word used to describe the spots of paint essential to this style of painting, though this term was initially rejected by Seurat.

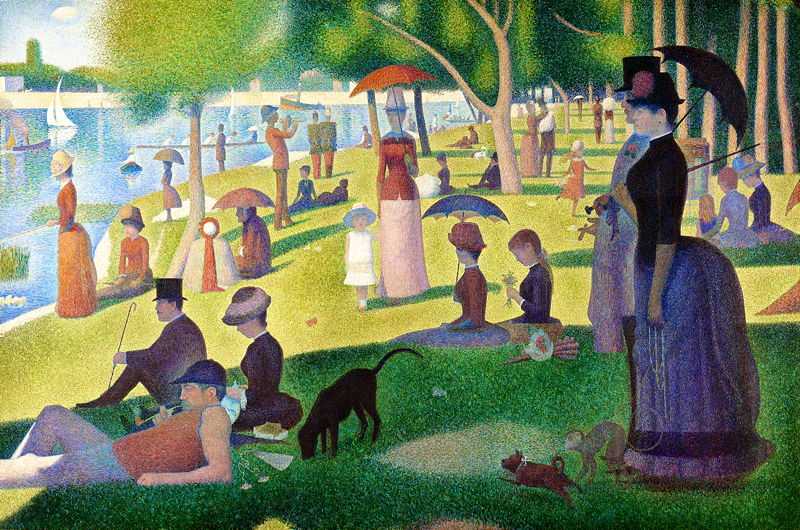

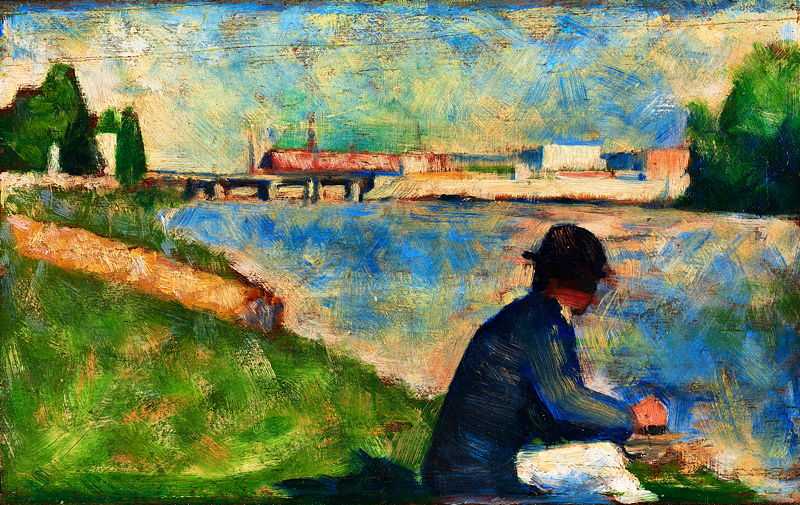

Seurat’s first and arguably best-known works were ‘Bathers at Asnières’ from 1884, followed by ‘Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte’ from 1884-86. With these paintings, he sought to bring his work into the public eye and both were made to the scale of major Salon pictures, demonstrating his ambition.

The palette of these paintings borrows from the bright, airy style of the Impressionists but the rigid approach to the application of paint sets it firmly apart from Impressionism. Similarly, Bathers at Asnières has the stately composition of a Neo-classical painting.

These paintings delivered almost a manifesto for the Neo-Impressionist technique, firmly laying out Seurat’s radical new style. Both works feature scenes from the banks of the Seine, depicting working-class figures at their leisure to deliver a dose of modernity to the paintings. This aspect further contrasted with the early works of prominent Impressionists like Monet and Renoir, who preferred to paint bourgeois figures instead.

Fame and fortune

Seurat’s dedication to forging his own path in French art gave him immense fame very quickly. When La Grande Jettee was shown at the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition in May 1886, he was quickly named the leader of a new form of avant-garde. By the end of that year, his work was being shown internationally.

The tight, restricted nature of these earlier paintings gradually gave way to looser forms of Divisionism in Seurat’s works.

‘The Harbour of Honfleur’ from 1886 is one such example, using softer spots of paint that are spaced wider across the canvas. Nonetheless, they still utilise the effects of optical mixing to great effect. This was one of many paintings made by Seurat at Honfleur and he produced a number of detailed sketches ‘en plein air’ before creating the larger pieces in his studio.

The Models

Between 1886-8, Seurat wanted to use pointillism to paint the human figure. The resulting masterpiece, The Models, is set in his studio and has Le Grand Jatte in the background. And Seurat proved that his method worked when painting flesh. Not that all the critics agreed. In an article redolent of the abuse received by the impressionists a decade earlier, one described the Models as:

“A studio where three nude women, painted in the pointillist manner, expose pathetic, rachitic skeletons smeared with all the colors of the rainbow.”

But The Models was indeed a masterpiece, perhaps inspired by Manet's Olympia and in turn an inspiration for Picasso's own masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Later works

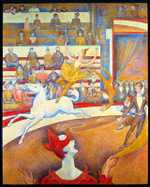

In his later work, Seurat transitioned from the tranquil scenes of his earlier paintings towards a more dynamic and whimsical style, taking inspiration from caricatures and advertising posters.

Once again, the young artists demonstrated his innovative approach to painting, doing away with the statuesque stillness of his youth in favour of fluidity and movement. This is evident in works like ‘The Circus’ from 1890-91, taken from an 1888 poster for the Nouveau Cirque, which depicts a horse mid-gallop and performers frozen during their acrobatic stunts.

This particular painting would be Seurat’s last. Indeed, it was unfinished at his death. Almost predicting his fate, Seurat chose to exhibit the work only partially completed in the Salon des Independants. His friend and fellow Post-Impressionist Paul Signac purchased the painting soon afterwards.

Upon his death, Signac took up the mantle of Neo-Impressionism and continued to develop the techniques further, building on his earliest works created as a disciple of Seurat. Signac enabled the momentum of the movement to continue, introducing the technique to an array of critics and writers and firmly establishing its reputation as an enduring art form.

4. Seurat’s legacy

Much like his father, Seurat chose to live in secrecy for the majority of his adult life, isolating himself in a little studio located in the Passage de l’Elyse-des-Beaux-Arts.

Madeline Knobloch

Here he resided with his first love, Madeline Knobloch, who he had met around 1888. She was only 20 at the time and served as the model in many of his artworks. The couple had a son, Pierre Georges, hidden away from family and friends.

A painting dated to 1888-1890 titled ‘Young Woman Powdering Her Face’ is a caricatured portrait of Knobloch. Though the figure is captured in the middle of a sweeping movement, the work has a stateliness and gravitas that makes it seem static. Her figure is solid and curvaceous, contrasting with the delicateness of the setting. Despite the painting being shown in 1890, Knobloch’s identity was not revealed.

Seurat’s early death

Tragically, Seurat died in 1891 at the age of just 31 from an infection and complications. His son died from the same infection within two weeks, having lived for little more than a year. The art critic Jules Christophe wrote that “A sudden, stupid sickness carried him off in a few hours when he was about to triumph: I curse providence and death”.

Later investigations indicate that Seurat most likely died of diphtheria. Following the deaths of her son and lover, Madeline disappeared. Records indicate that she too died young, from cirrhosis of the liver at the age of 35.

Seurat’s untimely death meant that his artistic legacy was abruptly cut short. Despite producing just 40 odd paintings, only seven of which were monumental, he succeeded in pioneering a new artistic vocabulary at a time of great innovation and creativity in French art. The fact that this was accomplished in such a short space of time, when he was only in his twenties, further adds to the impressiveness of the feat.

Among his contemporaries, Seurat’s approach to painting sparked the work of Signac and a rapid development in the paintings of Camille Pissarro who made the shift to Neo-Impressionism following Seurat’s example. Many other Impressionist artists also began incorporating Neo-Impressionist techniques into their work.

Influence on Van Gogh

Perhaps most important, however, was Seurat’s influence on Vincent Van Gogh. Van Gogh would borrow from Seurat’s techniques to produce an entirely new form of Post-Impressionist expression. The echoes of Seurat’s work is most evident in many of Van Gogh’s self-portraits, which blend different spots of colour and short, quick brushstrokes to build up a whole image.

The legacy of Seurat and the techniques he developed are far-reaching to this day. The Pointillist movement inspired a great number of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists and continued to ripple through the art world long after his death. From Pop Art to today’s pixelated Digital Art, Seurat’s explorations into colour theory and his careful, dotted applications of paint were monumental. His short life only serves to make his legacy even more incredible.