1. Reasons to Read

There are plenty of reasons to read Growing Up with the Impressionists.

1. The Impressionist Circle

One of the amazing things about the impressionist movement is the fact that the core participants formed strong and lasting bonds of friendship.

This is a recurring theme in the book, for example when Monet, Renoir and Degas organise an exhibition of Morisot's works after her death; and when Claude Monet in particular organises an exhibition and sale of Alfred Sisley's works after his death to support his impecunious widow.

On this latter point, Julie writes on 29 April 1899 as follows:

"We attended the view of the paintings which were left in Sisley's studio [on his death] and which are to be sold for his children, as well as others donated by various artists. Monsieur Monet, who is organising it, asked me for one of Maman's canvases, and I of course gave him one: Maman would certainly have done the same to help the children of an artist who exhibited with her for so many years. ..."

You also get a good feel for the characteristics of a number of the impressionists, in particular the oddities of Edgar Degas. As Jane Roberts' 20-page introduction to the diary explains:

"In his old age, Degas became crankier and more bad-tempered: he didn't approve of any newfangled contraptions such as telephones, aeroplanes or even bicycles, finding them 'ridiculous'; he hated dogs, the country, the sea and especially flowers ...."

These points come out of the diary which follows. For example, when describing an exhibition for her late mother's works that was being organised by Monet, Renoir and Degas, she explains a huge row about where to place a screen and a sofa. Julie then recounts the following:

"'What do I care about the public?' shouted Monsieur Degas. 'They see absolutely nothing - it's for myself, for ourselves, that we are mounting this exhibition, you can't honestly mean that you want to teach the public to see?'

'I certainly do', replied Monsieur Monet, 'at least, we want to try. If we had put this exhibition on just for ourselves, it wouldn't be worth going to the trouble of hanging all these paintings ....'

...

It was dark by then, and, as he spoke, Monsieur Degas paced back and forth in his great hooded cape-coat and top hat, his silhouette looking terribly comical. Monsieur Monet, also on his feet, was beginning to shout; ... Monsieur Renoir, totally exhausted, was sprawled on a chair. The porters at Durand-Ruel's [gallery] were laughing, saying: 'You watch [Degas]: he'll never give in.'"

On another occasion, Julie recounts another row between Degas and Edouard Manet. This time it probably wasn't Degas' fault! As Julie explains:

"This portrait was the cause of a serious argument. Monsieur Degas had painted Tante Suzanne at the piano with [U]ncle Edouard lying on a sofa listening to her playing. Finding that his wife looked too ugly, my uncle simply cut her out of the image. Monsieur Degas quite reasonably was terribly angry about this and took back the canvas [which he had given to Manet as a present!]"

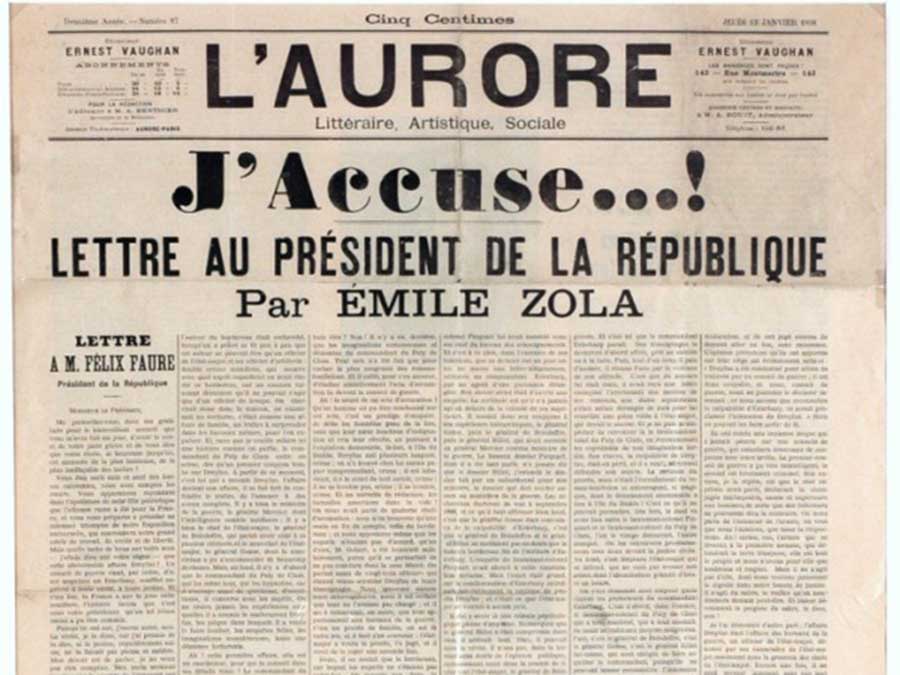

2. The Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus Affair was a decade-long political scandal that rocked France in the late 19th century. In essence, the army framed a Jewish officer when it transpired that military secrets were being leaked to the Germans. They then covered up, on the instructions of high-ranking politicians, evidence of Dreyfus' innocence.

The Dreyfus Affair exposed a fault line in the impressionist movement. Monet and long-time supporter of the impressionists Emile Zola were pro-Dreyfus (or Dreyfusards).

It is well-known that Edgar Degas was anti-Dreyfus, and did nothing to hide his shocking anti-Semitism. This is confirmed in Julie Manet's diary. For example, the entry for 20 January 1898 says:

"... we had gone over to invite Monsieur Degas [to dinner], but, finding him in such a state about the Jews, we'd left without actually asking him."

The position of Auguste Renoir is usually said to be less clear: it is hard to accept that this painter of joyous scenes who had an uncanny ability to capture the female form could be anti-semitic.

Yet this is precisely what Growing Up with the Impressionists reveals. For example, an entry for 17 March 1898 describes how Renoir and Mallarme came to dinner and the conversation turned to the Dreyfus Affair. Renoir is recorded as having commented

"... the peculiarity of the Jews is to cause destruction and disorder ..."

A later entry, for 2 August 1899, records Renoir as having disparaged a painting by Moreau by saying "It's art for Jews."

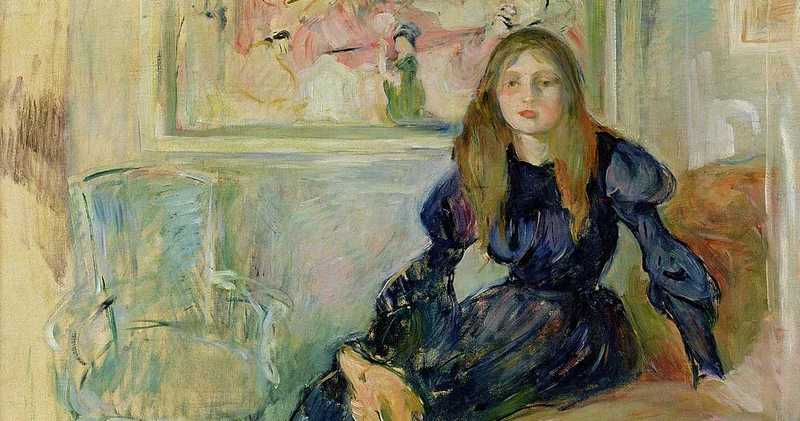

3. Degas and Renoir caring for Julie after Berthe's death

It is easy to paint people as all good or all bad. But life is more complicated than that. And so, whilst their views on Dreyfus are repugnant, it is interesting to note that Renoir and Degas took great interest in Julie after she was orphaned.

For his part, Renoir often took Julie on holiday, invited her over to dinner or popped in to see her, and gave her encouragement and advice on her own paintings.

Degas, with all his eccentricities and rage, was a less stable presence. But there is still lots of social interaction, with Degas being the person to introduce Julie Manet to her husband-to-be, Ernest Rouart.

For example an entry for 29 November 1895 (ten months after Berthe's death) includes the following observation:

"'Well, take a look at this little art collector!' cried Monsieur Degas, patting me affectionately under the chin. He gave me a kiss as we left and Monsieur Renoir, whom I always think of as our protector, saw us to the tram."

4. Paris in the Belle-Epoque

The 1890s was, of course, slap bang in the middle of the Belle-Epoque (c 1880-1914), a period characterised by economic prosperity, peace, and scientific and cultural advances.

This comes through in a number of the entries, including one for 6 October 1896 recording the Russian Tsar's visit to Paris. As Julie explains:

"After dinner, we went to 11 avenue Malakoff ... and found places on the balcony. ... The Trocadero is brilliantly illuminated and the Arc de Triomphe looks like a jewel against the black sky. At last, coloured rockets are set off all around the Eiffel Tower, illuminating the whole sky and shooting right up, all exploding at the same time and vying with each other for the honour of going even higher than the flag on top. . ... At the end of this extraordinary show, the illuminated image of Saint George appeared on the second platform of the Tower and all was suddenly black and quiet. Then a grand finale of rockets crowned this marvellous fireworks display."

2. Reasons to Pass

This is not a book for everyone.

Not for beginners

If you are looking for a book to introduce you to the impressionist movement, then this is not for you: the story starts after the key impressionist period has come to an end; and there is too much incidental detail about background matters to provide a solid introduction.

We suggest reading the Timeline page on this website, and then learning about the six key impressionists: Monet, Manet, Renoir, Cezanne, Degas and Pissarro. Once you've done that, we would suggest reading Sue Roe's The Private Lives of the Impressionists.

Too much detail?

This is also a book that requires a bit of patience (or a bit of skim-reading). Whilst there are many passages describing important events and personalities, there is -- as one would expect of a teenager -- lots of incidental detail.

Thus, the entry for 3 September 1893 records as follows:

"This morning we went on an excursion into the countryside, but the weather was horrid and gloomy. In the afternoon we stayed at the hotel painting and I did the Valvins bridge and the fireworks from memory. We then went to see Monsieur Mallarme in his study, which is decorated with rush matting and Japanese things, as well as brown material with roses on it.

As we wanted to send a basket of grapes to my godfather, Madame Mallarme took us to see a countrywoman, Madame Badet, who told us to come back tomorrow so that we could watch the grapes being picked."

Conclusion

But these are minor gripes. The translator, Jane Roberts, has done a good job at excising or summarising the more minor entries. And the book, which includes a helpful 20-page introductory summary, is only 198 pages long. We therefore highly recommend Growing Up with the Impressionists to those with a good base knowledge about impressionism who want to learn more about the movement, and indeed Paris, in the 1890s.