1. Disagreements

Initially, Morisot took the lead in organising the next Impressionist Exhibition.

Together with her husband, Eugène Manet, Morisot began approaching Impressionist artists at the start of 1886, to enquire about their interest in staging an Eighth Impressionist Exhibition.

Pissarro's Pleas

Pissarro was instrumental in the preparations too. He went to visit Mary Cassatt and Monet to invite them to exhibit with the Impressionists once again. As he had done in many of the prior Impressionist Exhibitions, Pissarro acted as the most tireless advocate for the merits of the group exhibitions.

Echoing previous exhibitions, the issue of Degas was raised again. The Impressionists agreed that Degas was an important member of the group, but they disagreed on whether or not he should be allowed to invite his countless friends and acquaintances to show their work.

Signac and Seurat

On top of the usual commotion was the added issue of Pissarro’s request; this year, he asked that Paul Signac and Georges Seurat also join the group.

By now Signac and Seurat had begun painting in their unique Pointillist style, developing the revolutionary technique that would come to characterise the Neo-Impressionist movement. In a bid to pursue a novel direction in his own work, Pissarro had also begun experimenting with Pointillist techniques, albeit with an Impressionist influence.

Convinced that Signac and Seurat had something to offer the Impressionist Exhibition, Pissarro wrote to his son, Lucien, describing his difficulties:

“I had a violent run in with M. Eugène Manet on the subject of Seurat and Signac. The latter was present, as was Guillaumin. [...] I explained to M. Manet, who probably didn’t understand anything I said, that Seurat has something new to contribute which these gentlemen, despite their talent, are unable to appreciate, that I am personally convinced of the progressive character of his art and certain in time it will yield extraordinary results. [...] But before anything is done they want to stack the cards and ruin the exhibition. M. Manet was beside himself!”

Degas' Demands ... Yet Again

Degas joined in the discussion and served to complicate the issue even further.

He insisted that the exhibition be held from the 15th May to the 15th June, which would put the Impressionists’ show on exactly the same dates as the official Salon. He intended it to be a strong statement in opposition of the Salon, but the others felt that this was a ridiculous demand.

Nonetheless, somehow his choice prevailed despite the overwhelming majority against it and the exhibition ran on those dates.

Funding

Another persistent issue was the lack of funding available to the group.

Morisot quickly became disillusioned with the in-fighting and withdrew her support from the exhibition, along with Monet. At the same time, Degas and Cassatt were unwilling to finance the exhibition themselves.

Pissarro had no funds of his own and so, together with Armand Guillaumin who was also trying to act as a peacekeeper and co-organiser, he looked in vain for solutions. Exactly where they would find the money for their exhibition was unclear.

2. The Artists & Exhibition Space

The Line-Up for the Eighth Exhibition was a shadow of what it had been for the previous exhibition: there was to be no Monet, Renoir, Sisley or Caillebotte.

To make matters worse, the exhibition space was remarkably cramped.

The Line-Up

Much to Pissarro’s dismay, Monet dropped out of the exhibition before it even began, closely followed by Renoir and Caillebotte. Renoir because he would not exhibit without Monet and Caillebotte most likely because he would not exhibit without Monet and with Degas. Similarly, Sisley also declined to take part.

Paul Gauguin joined the Impressionists once again and he introduced his friend Emile Schuffenecker to the group. Overall, Schuffenecker’s work lacked originality and Pissarro was against his admittance to the exhibition. He was overruled by Morisot and Eugène Manet, who both agreed to Gauguin’s request.

It was eventually agreed that Seurat and Signac would be permitted to show their paintings with the Impressionists, but they were given a separate room. Pissarro’s Pointillist inspired works joined them. Similarly, this exhibition featured the work of Lucien Pissarro, Camille’s son, who showed his watercolours and woodcuts in the same room.

Due to the loss of many of the artists who had exhibited at the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition, the only Impressionist works on display in 1886 were those by Morisot, Guillaumin and Gauguin.

All of the works contributed by Pissarro were painted in his new, lyrical and very personal take on Pointillism.

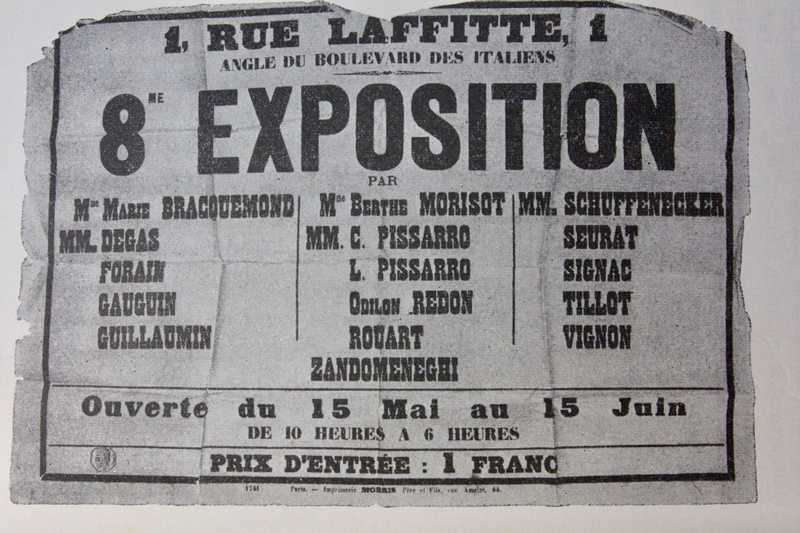

In addition, Degas invited Marie Bracquemond, Jean-Louis Forain, Henri Rouart, Charles Tillot and Federico Zandomeneghi to take part in the exhibition.

Raffaëlli

Mercifully, Degas dropped Jean-François Raffaëlli from the exhibition after he had been such a point of contention between him and the other Impressionists. Raffaëlli had chosen to exhibit at Georges Petit’s Exposition Internationale, demonstrating his loyalty elsewhere and thus making it a point of pride for Degas to reject him - though the decision had already been made by Raffaëlli himself. Incidentally, Monet, Renoir and Sisley also chose to contribute works to Petit’s show.

New Blood

There were two further exhibitors who were new to the group: Countess de Rambure and Odilon Redon.

Odilon Redon only contributed a collection of drawings, which were rather unceremoniously hung in the hallway. Meanwhile, Countess de Rambure is thought to have contributed a number of Realist works.

In a letter to Pissarro, from 1881, Caillebotte criticised Degas for bringing in a “Mme de Rambure” in both 1876 and 1877 but her works were not listed in either catalogues for those exhibitions. Her name was also missing from the 1886 catalogue but historians are certain of her inclusion in the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition thanks to a quip from the critic Félix Fénéon, who wrote that,

“The catalogue did not dare to mention her works.”

The exhibition space

A location for the exhibition was found on the corner of Rue Laffitte and the boulevard des Italiens, on the second floor above the restaurant Maison Dorée.

At this time, the Maison Dorée was arguably one of the most famous restaurants in Paris. It was frequented by a largely bourgeois clientele, as well as artists, art dealers and writers. This ensured a healthy number of potential visitors for the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition.

Once again, the name ‘Impressionists’ was omitted, and the exhibition was simply titled ‘Eighth Exhibition’. The group had been forced to exclude the word ‘Independants’ due to the competition from the new ‘Salon des Indépendants’, first held in 1884.

However, in a letter to Félix Bracquemond, Degas admitted that, “The premises are not as large as they should be, but are admirably situated.” This casual phrasing did not describe the extent of the issue; the space was so small that Signac and Seurat’s paintings were consigned to a narrow room, which prevented them from being seen from a distance. As a result, the full effect of the pictures made from the thousands of tiny daubs of paint could not be seen, nor could their use of optical mixing. Thus, the unfortunate decision completely nullified the intention of the artists.

3. Responses to the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition

The most important artwork in the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition was ‘La Grande Jatte’ by Seurat.

La Grande Jatte

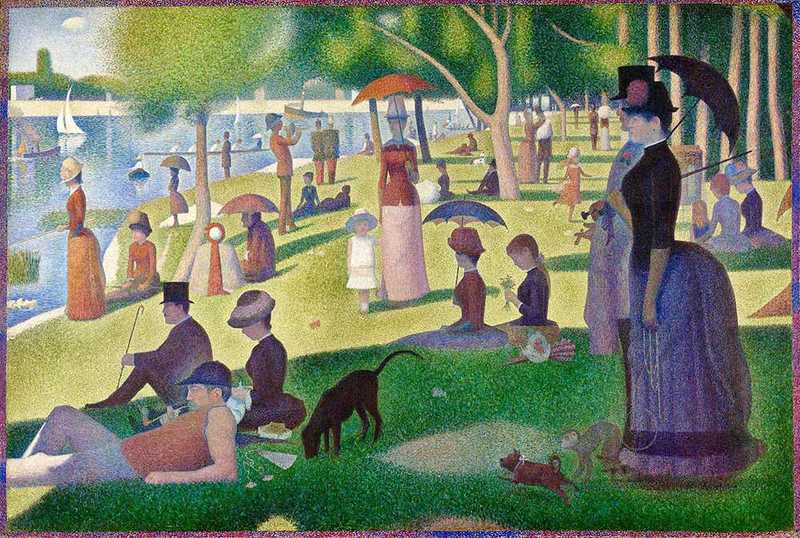

La Grande Jatte was an island in the river Seine. Seurat pictured its banks on a Sunday afternoon, bustling with well dressed Parisians enjoying the summer weather.

The work is Seurat's most famous of Seurat'e oeuvre. It is also enormous, measuring over 207 x 308 centimetres.

Its full name is A Sunday Afternoon of the Island of La Grande Jatte (Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte). It is now found in the Chicago Institute of Art

Reaction to La Grande Jatte

As the Impressionists had experienced many years before, Seurat’s Pointillist work was met with

“boisterous laughter, exaggerated in the hope of giving as much pain as possible.”

One of the aspects that caused much amusement was Seurat’s inclusion of a woman holding a monkey on a leash. Though they were displayed in a narrow back room, visitors pressed forward to see the paintings.

Years later, Signac described how an old friend of Édouard Manet, Alfred Émile Stevens

“continually shuttled back and forth between the Maison Dorée and and the neighbouring Café Tortoni to recruit those of his cronies who were sipping on the famous terrace, and brought them to look at Seurat’s canvas to show how low his friend Degas had fallen in welcoming such horrors. He threw his money on the turnstile and did not even wait for change, in such a hurry was he to bring in his forces.”

Though the general response was amusement, there were some viewers who were genuinely intrigued by the new technique. Similarly, many of the artists were captivated and admiring of Signac and Seurat’s inventiveness. The Belgian Poet, Emile Verhaeren, was one among very few critics to compliment the artworks, but this bravery then turned the ridicule on him!

Pissarro's Pointillism

As for Pissarro’s interpretations of Pointillism, the opinions were largely the same. His new acquaintance, the novelist Octave Mirbeau, dismissed Pointillism entirely, even questioning the sincerity of Seurat and his followers.

Other friends and supporters of Pissarro appear to have drawn the same conclusions and he was forced to confront the loss of popularity and respect that he had worked so hard to build.

George Moore was one of the few attendees who invested time and energy in trying to understand the new artworks. He had heard about Seurat’s painting from a friend who described an enormous canvas with a highly unusual colour palette and a lady with a monkey, the tail measuring three yards long! When he went to see the work for himself, he was likely a little disappointed at the diminutive size of the actual monkey. Nonetheless, he got down on his hands and knees in order to examine each of the Pointillist artworks in more detail.

Among the comments made by Moore was the critique that the works could not easily be told apart. It took him scrutinising the paintings up close to be able to distinguish between Seurat and Pissarro. This was in no small part due to the extremely poor way in which the artworks had been hung, but it was a verdict that was echoed by many critics who attended the exhibition.

Gaugin

One artist who had rather more success in the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition was Gauguin; he wrote to his wife, saying proudly,

“Our exhibition has re-opened - and favourably - the whole question of impressionism. I have had great success with artists. M. Bracquemond, the engraver, has purchased with enthusiasm a picture for 250 francs and has put me in touch with a ceramicist, who plans to do art vases. Enchanted with my sculpture, he wants me to make models for him this winter according to my fancy.”

The sculpture Gauguin referred to was a wood relief he had carved in 1882. More importantly, however, was the influence that the work of Signac and Seurat would have on Gauguin. He recognised at the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition, where his paintings hung side by side with the new Pointillist paintings, that his work lacked originality and colour. Colour was the vital element still missing from his paintings.

Degas the Voyeur

The Eighth Impressionist Exhibition further featured pastels by Degas, demonstrating a different direction for his works too. He described the series of nude figures as, “bathing, washing, drying, rubbing down, combing their hair or having it combed. To produce his pastels, he brought tubs and wash basins into his studio and instructed his models to use them as they would at home.

The resulting works depict the women in unconscious, habitual poses. It is both intimate and voyeuristic, “as if you looked through a keyhole” in Degas’ words. In many ways, the pastels echo a previous submission by Gauguin titled ‘Study of a Nude’ or ‘Suzanne Sewing’ from 1880.

The critical response to Degas’ works took a largely scandalised tone. However, Joris-Karl Husymans interpreted the drawings as displaying an, “attentive cruelty, a patient hatred.” In his eyes, Degas has produced the works as a “retaliation” intended to,

“throw in the face of his century the most excessive outrage, the destruction of the invariably respected idol: woman”.

On the other hand, he also summarised his review by saying,

“If ever works were chaste, definitely chaste, without dilatory precautions and without artifice, these certainly are! They even glorify the scorn of the flesh as no artist, since the Middle Ages, has dared to express it.”

4. The Aftermath

On the final day of the exhibition, the artists did not wait around for their customary debrief in a nearby cafe.

Seurat described how the participants, “disbanded like real cowards.” Many went immediately to see the opening of Petit’s ‘Exposition Internationale’.

Durand-Ruel's American Adventure

Running in parallel with the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition was a new venture from Durand-Ruel: an Impressionist exhibition in America. At the beginning of 1886, he set to work compiling over 300 canvasses to send across the Atlantic and in March 1886, he departed for New York.

As well as a large number of paintings by Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Manet, Morisot, Sisley and Degas, Pissarro had also been successful in convincing Durand-Ruel to take some pre-Pointillist works from Signac and Seurat with him too. Durand-Ruel’s grand American exhibition was announced as ‘Works in Oil and Pasel by the Impressionists of Paris’.

His return to Paris, shortly after the closing of the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition, was met with great speculation. In fact, Durand-Ruel was able to report that America promised a bright future for the Impressionists.

His exhibition had been far more successful than he had dared hope and he wrote to Henri Fantin:

“Don’t think that the Americans are savages. On the contrary, they are less ignorant, less bound by routine than our French collectors.”

Durand-Ruel’s positive reception was helped in no small part by Cassatt’s tireless advocacy of the Impressionist movement in America. She had enlisted the help of John Singer Sargent, who had also taken up the mantle as one of the Impressionists’ chief supporters in the US.

Furthermore, Durand-Ruel’s reputation in America was bolstered by his early investment in the Barbizon School, which was now extremely popular among collectors there. Thus, the public and the critics who attended the exhibition were far less prejudiced than the French had been, they were willing to entertain the idea that works offered by Durand-Ruel were likely to have value.

Hope for the Future

The year of 1886 consequently left the Impressionists in an intriguing position. The Eighth Impressionist Exhibition had had a largely underwhelming impact on the reputation of the Impressionist movement, but it was by no means a disappointing year. Durand-Ruel’s headway in America was an encouraging sign that there was a market for Impressionist art outside of France, and indeed that they could be a great deal more appreciated there than they were at home.