1. Cafe Culture in Paris

During the latter half of the 19th century, the number of cafés in Paris increased dramatically.

Some figures suggest they rose from 4,000 in 1851 to 42,000 in 1885. Another estimate puts the number of cafés in France as high as 283,000 by 1835.

Social institution or threat to the republic?

Many of the records on French cafés are thought to have been lost or deliberately destroyed by the National Archives of Paris, partly as a result of 19th century political fears that cafés served as a meeting place for revolutionaries.

Hence, cafés were seen as a threat to the French government and were actively monitored by the police.

In fact, cafés were a key social institution. For the first time, they offered a space in which people could drink together in public, including women of the nobility. Many women were encouraged to visit cafés who would never have dreamed of entering coffee houses, one of the precursors to cafés. The act of sharing food and drink in cafés transformed drinking in public into an acceptable and positive social practice.

Manet's Woman Reading

Edouard Manet’s Impressionist painting Woman Reading from 1880-81 depicts a woman seated in a café, reading a magazine. Whilst the work was painted in Manet’s studio - the painting behind the woman is one of his own - it demonstrates the prevalence and acceptance of women in cafés.

Classes of Cafe

Cafés generally fell into three categories, each catering to a different social group. There were bourgeois cafés and working-class cafés, though many of these were wiped out during Baron Hausmann’s redesign of Paris. By the 1870s, there were also so-called ‘modest establishments’ which attracted working-class and middle-class clientele. In these spaces, people of different social classes could mix in a novel way. Café Frascati was one popular example of this kind of café.

The nature of the café as an indispensable daily meeting space is summarised in the writing of Edward King. Writing in 1867 he described how,

“The huge Paris world centers twice, thrice daily; it is at the café; it gossips at the café, it intrigues at the café; it plots, it dreams, it suffers, it hopes, at the café.”

Alcohol?

As well as coffee, cafés also offered patrons a range of alcoholic beverages. Between 1840 to 1870, it is estimated that consumption of alcohol tripled in Paris. With the increasing industrialisation of France, eating habits also changed.

The introduction of lunch or ‘dejeuner’, eaten at midday, increasingly led to people dining out. Cafés provided food in an informal setting and this niche contributed enormously to their popularity.

The Patron

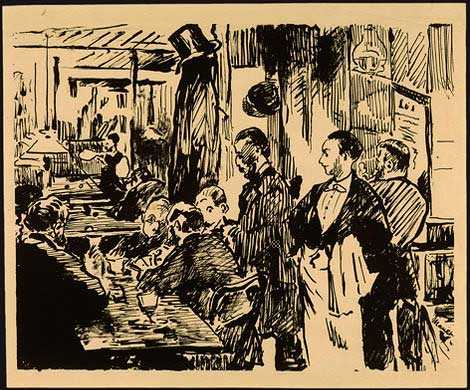

The role of the café owner is another important factor to note in the social function of cafés. Café owners would often act as mediators in their establishments, facilitating conversation and debate, intervening when needed, and offering advice. Working-class cafés were the first to use a counter or bar - where drinks would be displayed and poured, and the washing of glasses would take place - and this design added to the role of the café owner even further. On the other hand, bourgeois cafés largely maintained the use of waiter-service.

The Interior

The interior design of cafés underwent gradual modifications during the 19th century to make them feel more inviting. The addition of a mirror behind the counter, for instance, was a deliberate attempt to make the space feel more homely and less like a shop.

The presence of mirrors in working-class cafés also echoed the design of one of the first cafés, opened in 1689 by Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli, that had floor to ceiling mirrors to reflect the elegant lifestyle of his bourgeois customers.

La Patronne

Café counters also gave rise to the role of female café owners, especially in working-class cafés, and women employed to act in a sales capacity. Owners began introducing dress codes for their staff and women became an increasingly important connection between patrons and the goods the establishment sold. This ‘salegirl’ role was particularly important in bourgeois cafés.

A Third Space

Another factor in the popularity of Paris’ cafés was their importance as a meeting place away from the strict social responsibilities of work and the home. They also served as a prime vantage point from which to observe ‘ordinary life’ on the streets of Paris. Art historians have argued that this form of observing modernity became a way of life during the latter half of the 19th century, elevating the mundane aspects of the everyday into an object of wonder and spectacle. Cafés became, in the words of Susanna Barrows,

“the primary theatre of everyday life”.

2. The Café as an Intellectual Hub

As well as catering to ordinary people, cafés quickly became a central location for unconventional artists and intellectuals to meet.

They were often the space where radical ideas could be discussed and debated with energy. The café offered an alternative world that was distinct from the bourgeois characteristics of other popular meeting places. In this way they became a key feature of urban Bohemian life.

A Space for Artists

Unlike the tradition of patronage that had dominated in the 18th century, the 19th century brought an increasing desire for autonomy from artists, writers and intellectuals. Many of them sought to create their own spaces in which their work could be evaluated by fellow artists. Rather than meeting in their masters’ studios, the café offered a space for free thinking. It was a place where comradeship between artists could flourish.

Writers, artists and musicians all wanted a way to change how they were able to practice their trade. The café was a place where they could work to achieve this common goal. A typical café scene is described in this passage, written in 1860:

"In the beginning the café was a place where young people could meet, mix freely, speak openly of politics and literature. Often the proprietor of the establishment participated in these informal meetings, sometimes even presiding, not particularly concerned about making money. He was happy to provide his small clientele with an ordinary room and good drinks at a low price. These were the good old days of Bohemia and the Bohemian life.”

Montmartre

Montmartre was especially known for its literary cafés. Among literary circles, cafés were generally considered to be favourable to cabarets as meeting places. Many regulars had their own tables at their favourite cafés in Montmartre and friends would stop by to visit at all hours of the day. Afternoons and evenings could be passed simply talking and drinking coffee or wine, exchanging ideas about their work and current events.

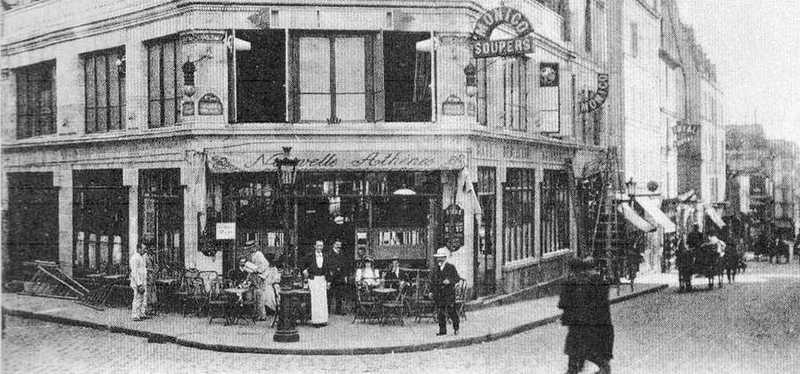

Popular cafés among the artists of Paris included Le Divan Lepelltier, Le Brasserie Andler, Les Brasserie des Martyrs, and the Café Tortoni. For the Impressionists, the favourites were Café Guerbois and Café de la Nouvelle Athénes. These locations became vital sources of social interaction and inspiration, offering a break from the solitary life of the studio.

Alfred Delvau summarised the importance of "the café” in the social lives of the intelligentsia in 1862, citing the café as the place where he and his friends would go,

“in order to show ourselves in good moments or bad, to chat to be happy or unhappy, to satisfy all the needs of our vanity or our intellect, to laugh or to cry.”

People-Watching

As well as the social draw of the café, cafés also provided the opportunity for intellectuals to examine people from outside their normal social circle, going about their ordinary lives. The café became the perfect backdrop to modern life, a window from which to examine working-class people and their social interactions.

Baron Haussman’s redesign of Paris introduced wide boulevards that cut across the city and these lighter, straighter streets provided an ideal location for tables and chairs to be placed outside. As a result, outdoor seating offered even more chance to sit and observe life as it passed by.

Edgar Degas’ painting ‘Femmes à la Terrasse d'un café’ from 1877 features a group of prostitutes seated outside a café on the boulevard Montmarte. Haussmann’s expansion of gaslighting throughout much of Paris meant that patrons could continue to sit outside even late into the night.

3. Drinking in Cafes

A popular drink in the cafés of Paris was coffee.

Officially first introduced to France by the Turkish ambassador in 1672, when he presented coffee served in gold-rimmed china to the court of Louis XIV, it is highly likely that coffee had already been present in France for much of the 1600s and perhaps even earlier.

Some cultural historians argue that coffee had been served in private in the homes of the French nobility from the 1640s.

Booze

As well as coffee, alcohol was also served in cafés. Changes to transportation and trade during the industrial era helped to lower the price of both alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks. The availability of more affordable drinking options and the increasing acceptance of drinking in public meant that it became more widespread, including among the working-class.

From the mid-19th century onwards, the range of drinks on offer also increased. As well as wine, many patrons would also drink beer, rum, Vermouth, Byrrh, eau-de vie and absinthe. With the spread of drinking as a form of social interaction there was also the evolution of several rituals that took place in cafés. The most recognisable of these are handshakes and the buying rounds of complementary drinks. Similarly, café owners began giving regulars nicknames, creating a sense of familiarity.

Absinthe

Closely tied with the café culture in Paris during the 19th century was the consumption of absinthe. Manet, Paul Gauguin and Degas would frequently drink absinthe and it became a feature of their work as well.

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh were among the artists most heavily affected by alcoholism, with Van Gogh being the most notorious. A still life from 1886 depicts a table, presumably in front of where he was seated, with a glass of absinthe and a water decanter. This early work was painted in the pastel colours of the Impressionist style.

Manet’s ‘The Absinthe Drinker’ from 1859 and Degas’ ‘L’Absinthe’ from 1875 are two of the most famous depictions of the pervasiveness of the drink during this period. ‘L’Absinthe’ was painted as the interior of La Nouvelle Athènes, though it was created in a studio. Degas drew on Japanese prints as inspiration for the off-centre framing and empty spaces seen in the work.

Interesting fact...

There were lots of names for absinthe, but the 'green fairy' and the 'green goddess' were two of the most common. Whilst it has been claimed that absinthe is a hallucinogen the boring reality is that it acquired its reputation because it is simply really strong (often served at 80 abv, about twice as strong as today's spirits).

Anti-absinthe campaigners seized on Degas’ grey and desolate painting as evidence of the drink’s corrupting power. Crucially, the consumption of alcohol was seen as problematic when it concerned working-class individuals and particularly women. It was later prohibited in France in 1914, in what the French Interior Minister described as an "act of self-defence". Pablo Picasso marked the day by creating his Glass of Absinthe sculpture.

4. The Impressionists in Cafés

In breaking away from the Salon and the control of the Ecole des Beaux Arts, the Impressionists adopted the café as a place in which they could develop their new art form.

Before they became well-known artists, they would gather in cafés in small groups to discuss their plans for the future and they regularly incorporated the everydayness of the café into their paintings.

Cafe Guerbois

Manet was slightly different to the other Impressionist artists in that he held on to his bourgeoise upbringing. He preferred to more fashionable Café Tortoni to the bohemian cafés many of his fellow Impressionist favoured. When he moved to Montmarte, he quickly developed a fondness for Café Guerbois at 11 Grande Rue des Batignolles.

In a book published in 1884 on Manet, Edmond Bazire describes the following who would gather with Manet at Café Guerbois:

“There were about twelve of them […] A. Legros, Whistler, Fantin-Latour would be joined by the writers Babou, Gignaux, Duranty, Zola; […] and finally, the latter arrivals, Degas. Renoir, Monet, Pissarro.”

They chose Thursdays as their regular meeting day and on Friday evenings, two tables were always reserved for the group.

The significance of Café Guerbois for the Impressionists was the feeling of camaraderie it gave them. This was the place in which they were able to discuss the change they all desired, despite their artistic differences.

An oil painting by Théodore Fantin-Latour from 1870 depicts the group, with Manet seated in front of an easel in the centre, holding a paintbrush. Behind Manet, one can identify Auguste Renoir, Émile Zola, Frédéric Bazille and Claude Monet. This painting hints at the constant sharing of ideas and critique that took place within the group.

It was at the Café Guerbois that the artists first discussed an independent exhibition, which would become the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874. Without independent galleries, cafés often operated as informal galleries where patrons could purchase work straight from the walls. The Impressionist exhibition was the first attempt by the Impressionists to stage a formal show that would be separate from the Salon.

La Nouvelle Athens

By 1875, the group had moved to La Nouvelle Athènes on Place Pigalle, following the influence of Marcellin Desboutin. Renoir, Manet and Degas became the most regular patrons, often joined by other emerging writers and art critics. Their conversation was as intense and spirited as it had been at the Café Guerbois.

George Moore described the different personalities of the Impressionists in this setting, writing that:

- Manet was “loud and declamatory”,

- Degas was “sharp, more profound, and scornfully sarcastic” and

- Camille Pissarro “sat listening, approving of their ideas, joining in the conversation quietly.”

Paintings of Cafes

Manet took the modern café as a setting for many of his paintings during the 1870s and 1880s. The first of these was ‘At the Café’ from 1878, a cropped image featuring several figures at the counter of a café. Several figures in the painting are cut out off, lending the image a photographic quality. The quick brushstrokes are typical of the Impressionist style and also add a feeling of immediacy to the work.

Manet’s paintings became a frequent feature in many of Paris’ bourgeois cafés in the second half of the 19th century. He had a close relationship with many café owners and they were a crucial conduit for him selling his work, as well as gaining clientele for portraits and commissions.

George Moore would later reflect,

“I did not go to either Oxford or Cambridge, but I went to La Nouvelle Athènes […] though unacknowledged, though unknown, the influence of the Nouvelle Athènes is inveterate in the artistic thought of the 19th century.”