1. Edgar Degas' sculptures

Only one piece of sculpture, The Little Dancer (Aged 14), was ever shown publicly by Edgar Degas.

But hundreds more were discovered in his studio after his death in 1917. Sculpted mainly in wax, these works were cast in bronze over the next two decades.

Here are 10 things you need to know about Degas' sculptures.

(1) The Little Dancer

‘Little Dancer Aged Fourteen’, first begun in 1879, was exhibited at the sixth impressionist exhibition of 1881.

Cast in wax by Degas, and accompanied by a bodice, tutu and ballet slippers, the Little Dancer is not so little - it is 98 centimetres tall. The work is modelled on Marie van Goethem, a ballet student and the daughter of a Belgian tailor and washerwoman.

The reviews of The Little Dancer were mainly negative. Whilst one critic wrote that "it is the first truly modern attempt at sculpture ...." others were harsh.

One called her a monkey, another an 'Aztec', and yet more said that the work

"bore the signs of a profoundly heinous character"

"is completely correct because this poor little girl is the beginning of a rat ...."

Relax, guys, it's only a sculpture ....

The Little Dancer was cast in bronze 28 times in the Hebrard foundry in Paris between 1920 and 1936. Copies are found in museums around the globe, with the original waxwork at Washington's National Gallery of Art.

A few are privately owned, one selling for £13,257,250 at a Sotheby's auction held on 3 February 2009. This sale, by Englishman Sir John Madejski to an unnamed Asian buyer, held the record for a Degas sculpture until Sotheby's sold another version of the Little Dancer for £15,829,000 in June 2015.

(2) Another 100+ sculptures

After Degas' death in 1917, a large number of sculptures were discovered hidden away in the artist’s studio.

These works ranged from dancers to bathers to horses. Impressionist dealer and gallery owner Paul Durand-Ruel recorded approximately 150 statues by Degas in all.

(3) Impermanence

What is notable about many of Degas’ sculptures is their impermanence.

The artist stated that he did not intend for the works to be cast into bronze. He also deliberately kept them private, away from the public eye. In this way, Degas’ sculptures differed from his paintings, showing a different form of experimentation.

Degas actually enjoyed the idea that his sculptures would gradually disintegrate over time. He wrote:

“My sculpture will never convey that perfection which is the ultimate in the art of sculpting, and since, after all, nobody will see these experiments, nobody will take it into their heads to talk about them . . . Before my death, all of this will disintegrate of its own accord.”

The art dealer Ambroise Vollard described a conversation he had with Degas in his studio:

“A number of wax figures in his studio bore witness to his activity as a sculptor. When I suggested having one of them cast: “Have it cast!” he cried. “Bronze is all right for those who work for eternity. My pleasure consists in beginning over and over again. Like this . . . Look!” He took an almost finished Danseuse from his modelling stand and rolled her into a ball of clay.”

(4) Better than Rodin?

Renoir is also said to have proclaimed to Vollard,

“Who said anything about Rodin? Why Degas is the greatest living sculptor! You should have seen that bas-relief of his . . . he just let it crumble to pieces.”

These quotes portray some of the aims of Degas’ sculptural experiments, putting impermanence at its heart. At the same time, Renoir’s statement is evidence that Degas was well known as a sculptor within his social circles.

(5) Unusual materials

One of the key elements of Degas’ sculptures was his use of novel materials.

In ‘Little Dancer Aged Fourteen’, he took care to use real fabric to make the dancer’s clothes and even included human hair in the piece.

Similarly, in ‘The Tub’, Degas used red-tinted wax, plaster and a real lead tub to create the work. The materials themselves were as important as the form. This would have been lost had he ever cast them into bronze.

Rather than using a wire armature which was the standard at this time, Degas used a range of materials, including cork covered in wire, then wrapped in starched cloth and finally wax.

(6) Casting into bronze

Degas' family had many of his wax sculptures cast into bronze between 1920 and 1926. Sixty-nine of the wax sculptures survived the casting process.

It was not until 1955 that the original wax sculptures came onto the art market. The majority of them are now held at the National Gallery of Art in Washington after being donated by Paul Mellon.

(7) Mallarme's influence

Jessica Locheed has linked Degas’ sculptures to the poetry of his contemporary, the writer Stéphane Mallarmé.

At the time when Degas was producing his sculptures, Mallarmé was reinventing poetry in the form of symbolist works. These pieces sought to move away from traditional poetic forms and instead were written to feel incomplete and instantaneous.

It is possible to read Degas’ sculptures in the same way. Indeed, the two men often discussed the theory of poetry together, as recounted by friends and acquaintances.

Through the 1880s and 1890s, Degas produced a wide variety of different sculptures. He is thought to have been partly inspired by contemporary sculptors, most importantly the works of Gustave Moreau.

It was at this time that Degas also began writing poetry, further adding to Locheed’s comparison with Mallarmé.

(8) Repetition ...

Later into his career, Edgar Degas' enthusiasm for remodelling his sculptures apparently faded.

As Vollard described,

“... he lost even his taste for destroying his wax figures in order to remodel them”.

Interestingly, Degas instead became fascinated by modelling figures in the same pose. There are four versions of ‘Dancer Looking at the Sole of Her Right Foot’, for instance, thought to date from 1910-11.

It is likely that these works were all made from the same sketch but Degas subtly tweaked the strokes he used for each piece. The physical structure was consistent throughout but Degas varied the method in which he produced the form.

- On one of these pieces, the strokes are far rougher.

- On another, Degas left obvious fingerprints.

- On a third, he deliberately omitted or discarded the dancer’s hand.

- A fourth of the sculptures appears to have been edited over time, with Degas returning to the work and either mending or altering it.

What is notable is that he left his changes as an obvious mark so that the corrections become a conspicuous part of the piece.

(9) Fleeting moment and everyday life

Like the paintings of the Impressionist movement, Degas’ sculptures sought to capture the fleeting moment and everyday life.

His dancers are caught in the middle of a movement that will no doubt change in a split second. ‘Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée)’ dated between 1885-1890 features a woman leaning precipitously over, one leg out behind her, both arms outstretched.

In these works, Degas did not attempt to capture any grand, monumental moment. Instead, he represented a single second from a scene of everyday life.

This is particularly evident from pieces like ‘Woman Seated in an Arm-chair Wiping Her Neck’. Like his paintings and pastels of women washing unselfconsciously, Degas represents a private moment. The figure’s body and the chair melt together, forcing the viewer to look closer to distinguish between the two.

Degas’ technique when working with wax imbibed his sculptures with the same textures as his pastels. He spent a great deal of time working on the texture of each piece, pressing flecks of wax onto the model to alter the light effects.

(10) Controversy

One cannot discuss Degas’ sculpture without mentioning the controversy caused by his ‘Petit Danseuse’.

First shown during the Impressionist exhibition of 1881, this piece sparked extreme outrage from visitors to the show with critics shunning the grotesqueness of the work.

This may be why Degas kept his later sculptures secret.

His later sculptures of ballet dancers are starkly different to ‘Little Dancer Aged Fourteen’. Works like ‘Dressed Dancer at Rest, Hands Behind Her Back, Right Leg Forward’ from 1895 are more unique and show the freeness that came with his later work.

2. Auguste Renoir's sculptures

Like Degas, Renoir did not begin sculpting until the later years of his life.

What is most surprising is that by this time he was suffering from severe rheumatoid arthritis.

Having turned to sculpture the age of 50, Renoir's arthritis became more aggressive to the point where he lost function in his wrists and joints.

Renoir lost the ability to pick up a paintbrush (they had to be taped to his hands) or hold a palette and walking became extremely difficult, confining him to a wheelchair. He continued to sculpt by issuing instructions to assistants.

Nudes

After moving to the south of France and buying a farm at Les Collettes, seen in his eponymous painting from 1908, he became captivated by figure painting, especially nude women.

This interest in figures and monumentality, as well as a desire to give his figures volume, eventually led him to sculpture. He was encouraged in this venture by the art dealer Ambroise Vollard.

Thanks to the financial security he had achieved by the time he reached old age, Renoir was able to pursue subjects that interested him rather than seeking out commissioned portraits. As such, he had the freedom to experiment with sculpture in a way that he hadn’t at any other point in his career.

At first, Renoir began working with small medallions but he soon moved onto larger sculptures. To create his pieces, he hired assistants to help as he was unable to use his hands in the way he needed.

Renoir's assistants

Richard Guino and Marcel Gimond were his choice of sculptors.

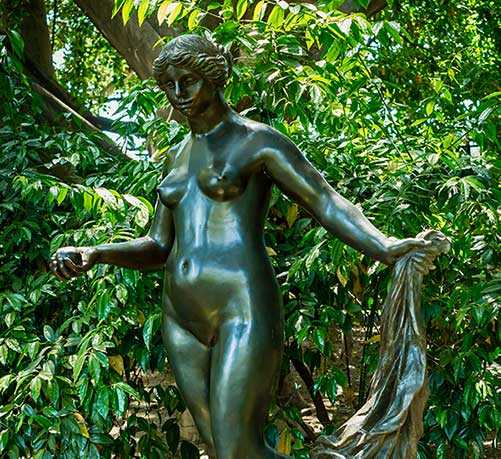

Guino was a Catalan artist who had worked with Aristide Maillol before becoming acquainted with Renoir. Together they created ‘Venus Victorious’, commissioned by Vollard.

Renoir would direct Guino to add or remove clay, shaping the work as he wanted. Using the hands of a far younger man, Renoir created his vision in 3D. ‘Venus Victorious’ was first modelled in clay and then Guino worked on a wax model.

Finally the piece was cast into bronze by a foundry in Paris. Whilst working with Renoir, Guiro and Gimond were forced to suppress their own artistic influences. However, after finishing their collaboration with the Impressionist artist, both Guiro and Gimond went on to become respected sculptors in their own right.

A little help from his friends ...

Renoir also enlisted the help of friends and family to help him with his work.

In 1914, just five years before his death, Renoir asked the post-Impressionist figurative painter Albert André to go to the Louvre on his behalf. He requested that he measure part of a statue of Venus, ideally ‘Venus of Arles’ or the ‘Medici Venus’.

In the final year of his life, Renoir worked with Louis Fernand Morel. Morel had been born in the same village as Renoir’s wife, Aline Charigot, later studying at the École des Beaux-Arts.

Together, Morel and Renoir produced terracotta reliefs of many of Renoir’s paintings from earlier in his career.

After Renoir’s death, Morel worked with his family to produce countless terracotta and bronze works from Renoir’s art in the following decades.

Renoir's interest in sculpture

There is evidence that Renoir was interested in sculpture from a very early age.

As his son Jean recounted in his 1962 book, Renoir had been enthralled by Jean Goujon’s ‘Fountain of the Innocents’ while studying at the studio of Charles Gleyre in Paris. This fountain was created to mark King Henry II’s 1549 entry into Paris and was located in the Les Halles district of the city.

What was notable about this work was Goujon’s new concept of bas-reliefs where figures were only slightly projected from the surface of the stone and fitted within a frame. This allowed him to created a feeling of volume using only a thin slab.

In 1810, Goujon’s bas-reliefs were removed from the structure to protect them from the water and they were displayed in the Louvre in 1824. It is likely that Renoir would have seen them there.

Sculpture inspiring painting

In Renoir’s later work, it is also possible to read the influence of sculpture on his painting.

‘The Bathers’ of 1887 draws inspiration from ‘Bathing Nymphs’ by Girardon at Versailles. Girardon was himself a follower of Goujon’s work who had revived the antique tradition of nymphs in art.

The bas-relief pioneered by Goujon also likely fed into Renoir’s chalk study of a female nude that depicts a figure with her face turned away, one arm outstretched and the other placed demurely in her lap.

The pose is extremely close to the Ancient Greek sculpture ‘Aphrodite of Knidos’ by Praxiteles from around the 4th century BC and this is a form that he returned to numerous times during his career, including ‘Bather with Griffin’ from 1870.

3. Berthe Morisot's sculptures

Catalogues of Morisot’s work exist listing watercolours, pastels, engravings and sculpture.

But very little is known of her experiments with sculpture. Unfortunately, her work has not achieved the same scholarly attention as Renoir and Degas.

Adèle d’Affry

It is likely that the biggest influence on Morisot’s sculptures stemmed from her friendship with the Swiss sculptor Adèle d’Affry.

Known in her professional life as Marcello, the artist served as a mentor to Morisot, as well as being a close friend.

In one of her notebooks, Morisot wrote that her relationship with Marcello was her best friendship. She described how they spent many days shopping and talking:

“We had everything to say to each other and I could dare to really confide in her.”

Marcello sought to represent important female figures from both her contemporary world and history and mythology. The running theme throughout her sculptures was the strength and authority of the figures she depicted.

Head of Julie Manet

With encouragement from Marcello, Morisot worked on sculptures of her own. ‘Head of Julie Manet’ from 1886 is one such work, which was cast in bronze. This piece was sold at auction by Christie’s in 2012.

Morisot also began studying sculpture under Aimé Millet (1819 - 1891) in the winter of 1863-64, perhaps on the advice of Marcello. At this time, there was a dearth of opportunities for women to study sculpture in France.

Mme Bertaux

Hélène Bertaux, known professionally as Mme Léon Bertaux, was one of the first people to establish educational courses for girls and women wishing to study sculpture.

In 1873, Bertaux founded the ‘ateliers d’etudes’ in Paris, aimed at offering high quality artistic education, specifically in sculpture. The success of these courses led to her establishing a sculpture school for women in 1879.

Betaux’s close involvement with her students made her acutely aware of the barriers women artists faced in achieving recognition for their work. She decided to form an organisation in order to represent women artists saying:

“Let us gather together to count ourselves, to defend ourselves! Let us be united for the faithful struggle. Let us call ourselves the ‘Union of Women Painters and Sculptors’”.

The Union organised exhibitions aimed at displaying all works by women equally, regardless of perceived talent or reputation.

Where are they now?

While Morisot would likely have followed the work of the Union, it is thought that the recognition she achieved in the independent Impressionist Exhibitions meant that the work of the union was less relevant to her.

Nonetheless, through her relationship with other artists she would no doubt have been aware of the Union. Sadly, Morisot’s sculptures are not part of any public collection and very little is known about their whereabouts today.

Please contact us if you have pictures of other Morisot sculptures.

4. Auguste Rodin's sculptures

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) was a contemporary of the impressionists.

Whilst direct contact with the impressionist circle did not begin until the 1880s, Rodin can nonetheless be described as an impressionist sculptor:

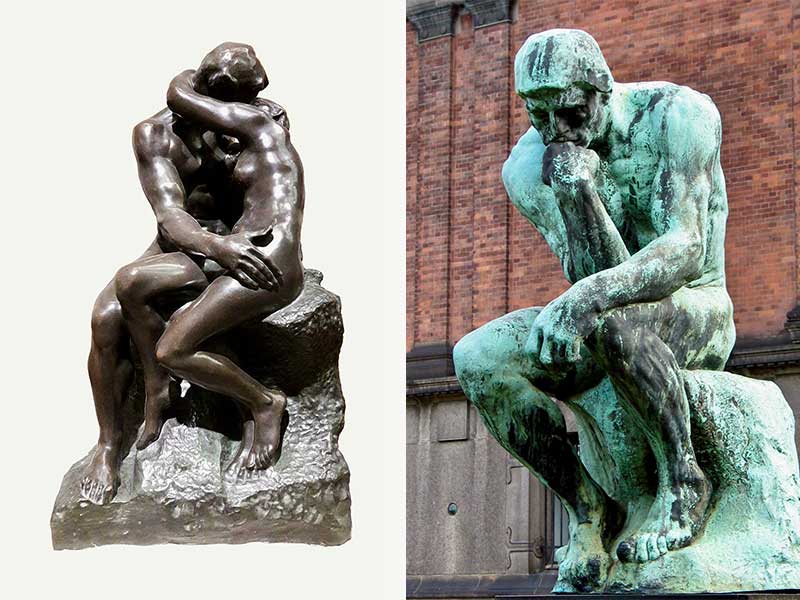

- Rodin challenged the orthodox approach to sculpture (religious, historical, mythological scenes) by producing daring works such as The Kiss.

- Rodin pushed the boundaries of sculpture, leaving his fingerprints on his works and experimenting with hollows and mounds (rather than producing works with smooth surfaces).

- Rodin and Monet struck up a close friendship and exhibited together in Paris in 1889 and in Boston in 1906.

Rodin's career

Rejected by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts on three occasions, Rodin resorted to teaching himself. He worked largely as a craftsman, but was inspired by the works of Michelangelo (which he studied during six years in Italy in the 1870s).

Rodin's breakthrough came when he was commissioned to produce the Gates of Hell (La Porte de l'enfer) in 1880.

The Gates of Hell

The six by four metre Gates of Hell was commissioned in 1880 and took Rodin until his death, 37 years later, to complete! It contains 180 figures and is inspired by Dante's Inferno. The central figure above the doors is Rodin's The Thinker, one of his most famous works. Rodin initially included the figures from The Kiss in the Gates of Hell, but removed the embracing lovers because they did not fit the fiery subject matter.

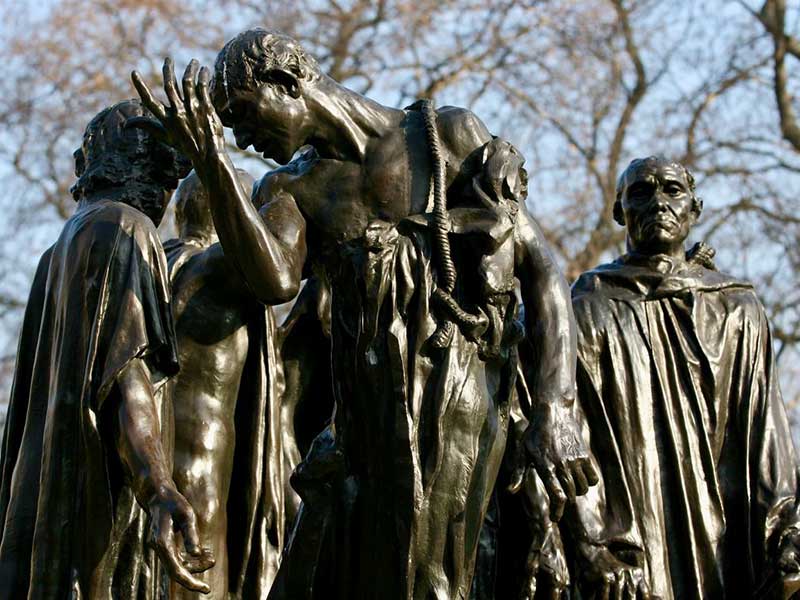

Rodin's career skyrocketed in the 1890s, when he started to make serious money from his work. It was during this decade that he produced his other key work, the Burghers of Calais.

The Burghers of Calais is a scene from the 100 Years' War. It depicts the elders of Calais meeting King Edward III and offering up their lives in return for the rest of the inhabitants of Calais being saved (Calais, by this stage, had been under siege for a year).

Edward III's wife, Philippa, heard of the men's bravery and asked for them to be spared, which indeed they were.

Monet and Rodin

Claude Monet and Auguste Rodin became firm friends in later life, meeting in the 1880s, and each admiring the work of the other.

They were almost exact contemporaries, being born two days apart in November 1840.

Monet and Rodin exhibited together at Galerie Georges Petit in Paris in 1889 and again in 1906 in the Copley Society in Boston.

Both exhibitions were huge successes, though Monet and Rodin almost fell out in the preparations for the 1889 exhibition when the (then very famous) Rodin placed one of his sculptures in front of the (then not so famous) Monet.

The 1906 exhibition was one of the largest Monet ever gave: his 111 paintings, including the Seine at Vetheuil, were complemented by 11 Rodin sculptures.

Degas and Rodin

A different duo - Degas and Rodin - have their sculptures on view at an exhibition in Bath’s Holburne Museum between September 2022 and January 2023.