1. Picasso’s early years

Picasso was born in 1881.

The first (little known) fact to note about Picasso is that his name was in fact 23 words long, incorporating the saints, relatives and the surnames of both his parents.

Here's the full version:

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Martyr Patricio Clito Ruíz y Picasso.

Ruiz or Picasso?

Later, Picasso would reflect that he chose to take his mother’s surname over his father’s - Ruiz - as he felt that it was more memorable and more resonant, stating that,

“the double 's', […] is fairly unusual in Spain. Picasso is of Italian origin, as you know. And the name a person bears or adopts has its importance. Can you imagine me calling myself Ruiz?”

Picasso moves to Barcelona

At the time of his birth, Picasso’s family were living in Malaga, Spain but they moved to Barcelona when his father, an artist and art professor, was given a new post.

Jose Ruíz Blasco began giving his son a formal art training from the age of seven. The story goes that by the time the boy was just 13, his father gave up painting as he believed that his son had already surpassed him. Indeed, Picasso completed his first painting in 1890, at the age of nine and his first major, academic painting at the age of 15, titled 'La Premiér Communion’.

In Barcelona, Picasso entered the School of Fine Arts in 1895 before entering the Madrid Academy in 1897. His earliest paintings showed a great level of confidence and talent. He was much younger than the majority of his classmates but already years ahead in terms of artistic ability. Despite this, he often found himself in detention as he clashed with his art masters. Here, in a bare, whitewashed room, he would spend many hours with a sketchpad, simply drawing.

Changing styles

One of the things that is most evident in Picasso’s biography is the regularity and rapidity with which he developed and shifted into new styles in his work. He was an incredibly innovative artist, constantly pushing his work towards new realms of expression and often working on several different styles in tandem, as well as incorporating numerous styles into a single artwork.

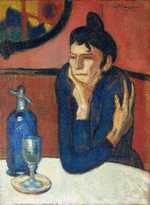

Young Picasso first visited Paris in the autumn of 1900, returning the following year for his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Vollard. These Neo-Impressionist works consisted of paintings largely depicting beggars and women, painted in the style of what is now known as Picasso’s ‘Blue Period’ thanks to the uniform colour palette he adopted.

Picasso's Blue Period is thought to have been brought on by the suicide of his close friend Charles Casagemas, with whom Picasso travelled to Paris (with the two men living together in Montmartre). Casagemas shot himself when his love for a Parisian woman went unrequited.

One painting that characterises the melancholy air of these works is ‘The Soup’ from 1902-03, thought to have been influenced by the religious paintings that surrounded him during his childhood in Spain.

As the birthplace of the Impressionists, Paris had by this time become firmly established as an international hub for art and artists. Unsurprisingly then, Picasso chose to settle permanently in Paris just three years later, in 1904.

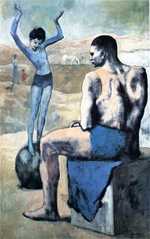

The Rose Period

This move saw his work transition into Picasso's ‘Rose Period’, so called because of his use of reddish and pink tones. During these years, he began painting Neo-Impressionist interpretations of circus performers in particular and his studio became a gathering place for writers, artists and musicians.

Gertrude Stein was a close friend and supporter of Picasso and she also sat for him a number of times. ‘Portrait of Gertrude Stein’ from 1905 is a key work that demonstrates an important stage in the progression of the young artist's experiments with finding his own style, which culminated in ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ in 1907.

The forms in his portrait of Stein appear both sculpted and flattened and this is most evident in the way her captured her face. Her features are strong and starkly outlined, each element appearing as a flattened plane, such that critics have described it not as a face but as a mask. This was an aesthetic that he would return to and refine throughout his career.

2. Picasso and the Impressionists

Shortly after moving to Paris, Picasso embarked on a more revolutionary path in his artworks, drawing inspiration from Cézanne and Henri Rousseau.

He would dismiss his earlier work, completed prior to this period, as trivial when referring to it in later interviews.

The influence of Cezanne

In fact, Cézanne was one of the most significant influences on Picasso from 1907 onwards. To Picasso, Cézanne was “my one and only master”. He became particularly interested by his technique after visiting a retrospective exhibition of his oeuvre shown in Paris in 1907, following the artist’s death the previous year.

Though Cézanne was an Impressionist painter, he had an ambition to make Impressionist art more solid and enduring and this led him down a different path to fellow painters in the Impressionist movement. Cézanne carved out his own, distinctive reputation as a Post-Impressionist artist that led to many modernist artists retrospectively hailing him as their idol.

Geometric Structure

Most crucially, the work of this particular Impressionist inspired in Picasso the concept of giving his figures a certain geometric structure. Cézanne’s interest in visual perception led him to essentialise many of the forms in his paintings, transforming objects and figures into pure, geometric shapes.

This can be best seen in Cezanne's later pictures of bathing men and women, especially in Large Bathers.

Cezanne played with the flatness of the canvas in representing a three-dimensional space and in doing so created works that distilled nature into basic forms. This crucial aspect of his work was what fascinated Picasso the most.

Moreover, he borrowed from Cézanne’s brushwork and in particular his technique of painting in a faceted, fracturing way. In many of Cézanne’s paintings, the brushstrokes themselves are angular and fragmented. This structural approach to painting eventually led Picasso towards Cubism and in his words:

"Cézanne's influence gradually flooded everything."

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

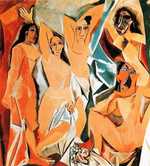

That the discovery of Cézanne was such a turning point in Picasso’s career is best demonstrated in ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’, painted the same year that he attended Cézanne’s posthumous exhibition.

The painting depicts four nude female figures, broken into angular shards and arranged in a flattened, chaotic plane that confuses the eye.

‘Les Demoiselles’ is radically different to Picasso's earlier works and represents a critical new direction for the artist, so much so that this work is considered to be Proto-Cubist or Pre-Cubist. To put it more romantically proclaimed André Breton in the 1920s:

“with this painting we bid farewell to all the paintings of the past” .

Like many artworks painted by the Impressionists before him, this piece was considered highly immoral when it was first exhibited publicly, which was not until 1916.

The outrage was of course not as a result of the nude female figures - a favourite subject among artists for many centuries - but the overtly sexual manner in which the figures are positioned.

Brazenness

The subjects pose in a blatant and unabashed way with their arms behind their heads, one figure on the far right squats with her legs open.

There is none of the blushing coyness that viewers were accustomed to seeing. In this way, Picasso depicted the women as prostitutes, making their faces into mask-like guises that stare blankly and brazenly.

The faces of ‘Les Demoiselles’ are thought to have been inspired by Iberian masks and African Negro art. Picasso visited an exhibition on Iberian sculpture at the Louvre in 1906.

Around this time he was also experimenting with elements of African Negro sculpture and such art was becoming more popular among young painters in Paris during the early 1900s. However, this influence was dismissed by Picasso in an interview many years later and he stated that the inspiration came solely from Iberian sculpture. Many critics nevertheless dispute this claim.

As well as the influence of Cézanne, later analyses of the work have also cited the influence of Édouard Manet’s painting ‘Olympia’ from 1865. This Impressionist portrait portrays a nude courtesan, lying on a chaise and looking directly at the viewer in an unabashed manner.

Manet rendered his sitter as a compressed and flattened form on his canvas. This painting prompted his friend Charles Baudelaire to prophetically state that, “you are only the first in the decrepitude of your art”. It is likely that this painting would have also had an important influence on Picasso’s work.

Cezanne's Character

As well as being engrossed by his art, note that Picasso was also fascinated by Cézanne’s character. He would later remark that,

“It's not what the artist does that counts, but what he is. […] What forces our attention is Cezanne's anxiety - that's Cezanne's lesson.”

Cézanne’s restlessness and creative hunger is in part what captured the attention of the modernist artists who devoured his works. He represented an ideal of innovation and self-sacrifice that was not shared by other greats of the Impressionist movement. This was partly why his influence was so enduring.

3. Picasso and Cubism

From ‘Les Demoiselles’ onwards, Picasso’s work became increasingly abstract.

It was also around 1907 that Picasso met Georges Braque and the two artists began to collaborate. It was this introduction that ultimately led to the development of Cubism.

Picasso and Braque

The initial introduction is thought to have occurred when Braque visited Picasso’s studio to see his most notorious artwork. Braque is said to have been so inspired after seeing ‘Les Demoiselles’ that he endeavored to paint his own Proto-Cubist paintings. He also made a firm decision to befriend Picasso.

In the years that followed, the two artists fed off of one another’s artistic output, oscillating between close confidence and collaboration and aggressive competition. They met daily and were almost inseparable, so much so that some of their paintings are difficult to tell apart.

Cubism

Over time, Picasso and Braque invented Cubism. The Cubist principles worked on deconstructing the conventions of perspective that had dominated perspective in art since the Renaissance.

The artists fragmented objects and rearranged them on the canvas, synthesizing multiple perspectives into the same work. They also chose to restrict their colour palettes in order to push their experiments with form and space to the fore. In doing so, Picasso and Braque took 20th century art in a radical new direction, diverging from the Fauvist movement and the movement’s focus on colour.

... and Collage

As well as working on Cubist paintings, Picasso was also motivated to begin collage. This medium enabled him to experiment in ever more daring and dynamic ways, deconstructing the idea of the picture as a window onto the world and instead transforming his works into symbolic arrangements of signs and metaphors. This phase of Cubism has since become known as the “Synthetic” period.

It is important to note that Picasso worked in several different mediums and styles in parallel during this period. Whilst he was still producing his later Cubist works, he was also making Neo-classical figure paintings between 1920-24.

Similarly, he was producing Cubist set designs for the Ballets Russes following a meeting with Jean Cocteau, which led him to the expressive and innovative impresario Serge Diaghilev. They collaborated on several productions between 1917 and 1922.

... and Surrealism

Picasso’s work began to shift once more from 1925 onwards when he began experimenting with more forcefully expressive works that were highly metamorphic. This move saw him align more closely with the Surrealist movement and he began exhibiting with the Surrealists frequently in the coming years.

Though Picasso never transitioned into becoming a Surrealist completely, he adopted a number of Surrealist techniques in his work. The effect of Surrealism on Picasso was far-reaching and diverse, from inspiring the soft, erotic forms in portraits of his mistress Marie-Therese Walter to the disturbing imagery of Guernica from 1937.

Guernica

Guernica has since been named one of the century’s most famous anti-war paintings. This mural-sized painting was created using an entirely monochrome palette of gray, black and white.

The enormous scale of the work means that the figures warp and envelop the viewer, creating a disturbing effect. Much speculation has gone into the meaning of the elements in the painting but Picasso said simply:

“In the panel on which I am working, which I call Guernica, I clearly express my abhorrence of the military caste which has sunk Spain into an ocean of pain and death.”

Certainly, pain and fear are evident, even from a first glance.

One of the most notable series in Picasso’s Surrealist period was the wrought-iron constructions and sculptures that he worked on between 1928-34.

At the same time, he also produced illustrations for a number of literary texts, including Ovid's ‘Les Métamorphoses’ and Buffon's ‘Histoire Naturelle’. He went on to write two surrealist plays of his own and a great deal of poetry, which it was rumoured he preferred to painting.

4. Picasso’s legacy

It is hard to summarise the extent of Picasso’s artistic legacy.

In many ways, his reputation has become so engorged and extended that it is no longer possible to describe his work in rational terms. Countless critics, journalists and scholars have poured over every aspect of his work and life, both when he was alive and since his death in April 1973.

What is known for certain is that the styles that he adopted, invented and pioneered during his lifetime would have a lasting and monumental effect on modern art to follow.

Picasso’s legacy includes the development of Cubism, which saw a revolutionary rewriting of the rules of perspective in art and would go on to have an earth-shattering impact on the development of Western art. He forged a new path for artists to experiment with the depiction of form in space, giving them the foundations to innovate in their own way for decades to come.

However, in the inevitably breathless account of Picasso’s influence, it is also important to note the earlier impact of the Impressionist artists who came before him. In particular, it is impossible to ignore the role of Cézanne in creating many of the visual techniques that Picasso would adopt and morph into his own works.

From mask like faces to radically flattened planes, Cézanne was the first to experiment with the techniques that captured Picasso and the public’s imagination. It was Cézanne’s influence that gave Picasso the tools which would lead him to being responsible for “the birth of modern art”, as many critics have claimed.

The Impressionists’ radical approach to painting was transformative in many ways and their profound influence on Western art in the 20th century should not be forgotten.