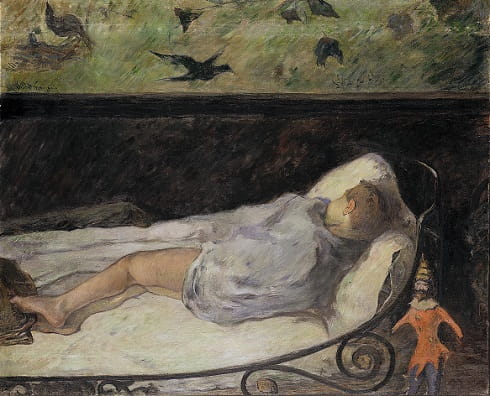

1. The Little One Is Dreaming (1881)

Depicting his daughter, Aline, asleep on a cot, Gauguin’s work ‘The Little One is Dreaming’ is an early example of his forays into symbolic painting.

At first glance, this piece appears to be realist in nature. But there are a few features that point towards the symbolism for which Paul Gauguin is best known.

Gauguin draws from his imagination to paint dreamlike representations into the composition. Above the child’s head, for instance, black birds are taking flight and a Punch toy hangs from the edge of the bed. This doll is a motif that Gauguin returned to frequently in his paintings.

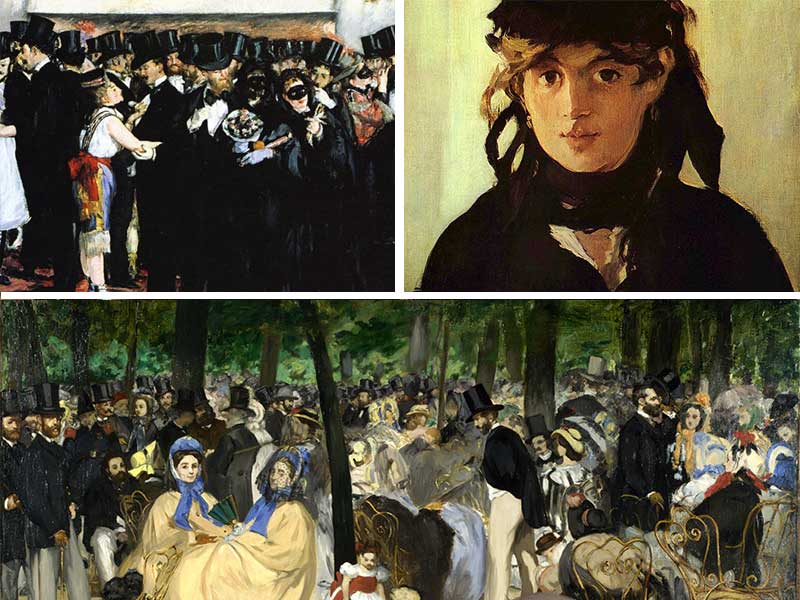

Impressionist influence

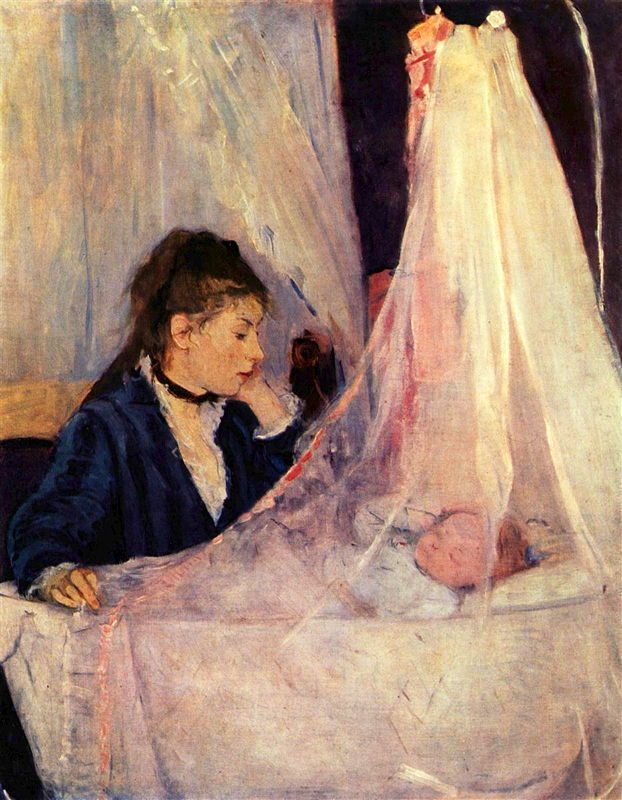

The quick, visible brushstrokes in the painting also demonstrate the influence of Impressionism on Gauguin’s work. Indeed, there are echoes of Berthe Morisot’s paintings of children in this piece.

However, the dark colour palette, which contrasts with the pale sheets, nightdress and skin of the child, also serve to make the piece feel threatening and ominous. The heavy use of black space in the painting is reminiscent of the work of Edouard Manet.

Into the subconscious

Though Gauguin regularly painted his family and images from domestic life in his early paintings, this piece does not seek to represent everyday life. Instead, it wrestles with the complexities of the subconscious.

The work remained in the collection of Gauguin’s Danish wife, Mette, until it was sold to the Danish collector, Wilhelm Hansen.

Where is it now?

The Little One is Dreaming is found in Copenhagan's Ordrupgaard. Gauguin moved about frequently during his life, spending some time with his parents-in-law in Copenhagen after he decided to jack in his career in finance to focus on art.

2. Landscape near Arles (1888)

One of very few landscapes Gauguin painted without human figures, ‘Landscape near Arles’ was produced while he was staying with van Gogh in Provence.

Rather than painting forms directly from nature, as in the work of Impressionists like Alfred Sisley, Gauguin instead simplified this landscape into a series of geometric forms.

Impressionist influence

The colours are also less naturalistic than other Impressionist landscapes and they do not focus on the effects produced by natural light. Indeed, his palette in this piece is far less bold and saturated than his other work from this period.

But this remains an important work: in Gauguin’s brushstrokes, it is also possible to read the influence of Impressionist techniques. The piece is made up of countless short, quick lines and dashes intended to capture the different textures in the scene.

Copying Cezanne?

In this piece, there are also clear parallels with the work of Paul Cézanne, a Provence native. Notice the similarities with Cézanne’s ‘House in Provence’ (1885) for instance.

Where is it now?

Gaugin's Landscape near Arles is now found in the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

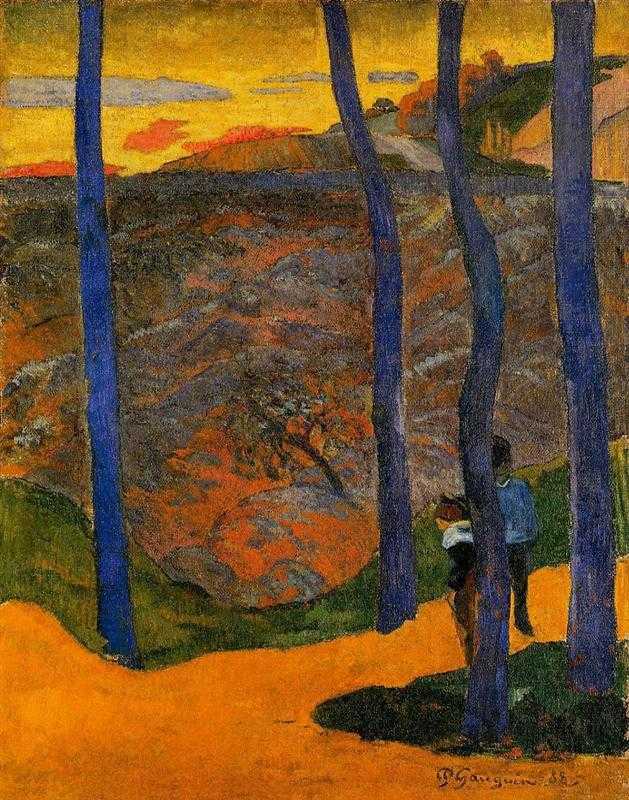

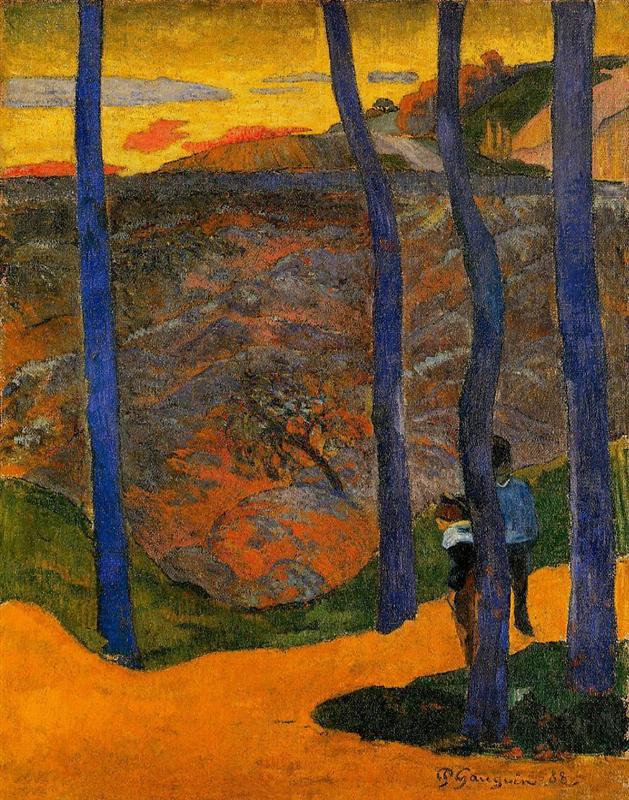

3. Blue Trees [Your Turn Will Come, My Beauty!] (1888)

During his stay with Van Gogh in Arles, Gauguin painted ‘Blue Trees’ featuring four strong vertical lines of bright blue tree trunks.

Between the trees, there is a landscape of dazzling, dreamlike colours: a yellow sky, red clouds, a line of blue undergrowth and a bright orange path.

Gauguin inspiring others

In this painting, it is easy to see how Gauguin’s work served as a source of inspiration for the Fauvist movement to come. The colours are stark and intense with heavy use of contrasting colours to create a striking piece which was extremely unusual for the 1880s.

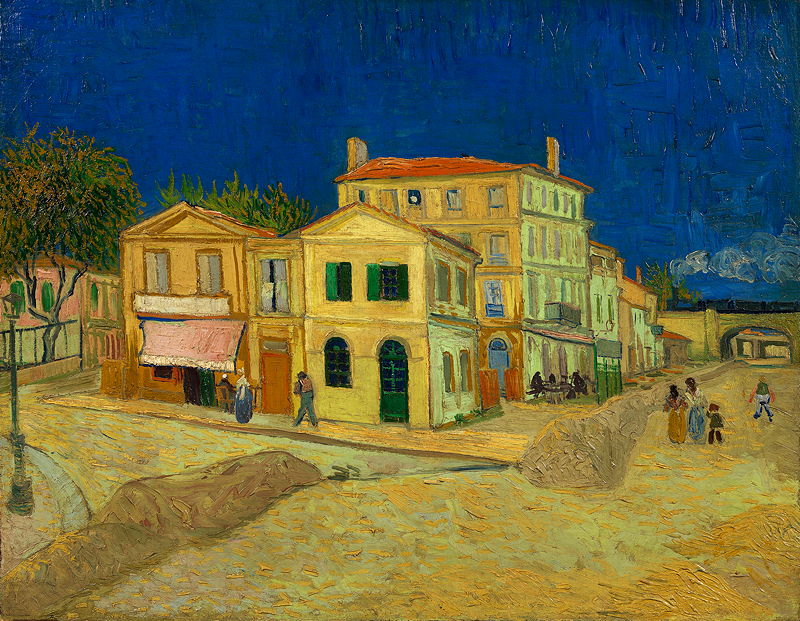

It is no coincidence that Vincent van Gogh was also experimenting with the use of similar colours at this time. Here's van Gogh's Yellow House, which also uses orange, yellow and blue.

The two figures

Turning to the foreground of Gauguin's work, the viewer catches a glimpse of two figures.

One has their hands deep in their pockets and both the figures’ faces are obscured. The combination of the strange landscape with the faceless couple lends the work an unsettling atmosphere.

This is echoed by the subtitle for the piece - ‘Your Turn Will Come, My Beauty!’ - which adds to the sinister feel.

Where is it now?

Blue Trees is now found in Copenhagen's Ordrupgaard Collection.

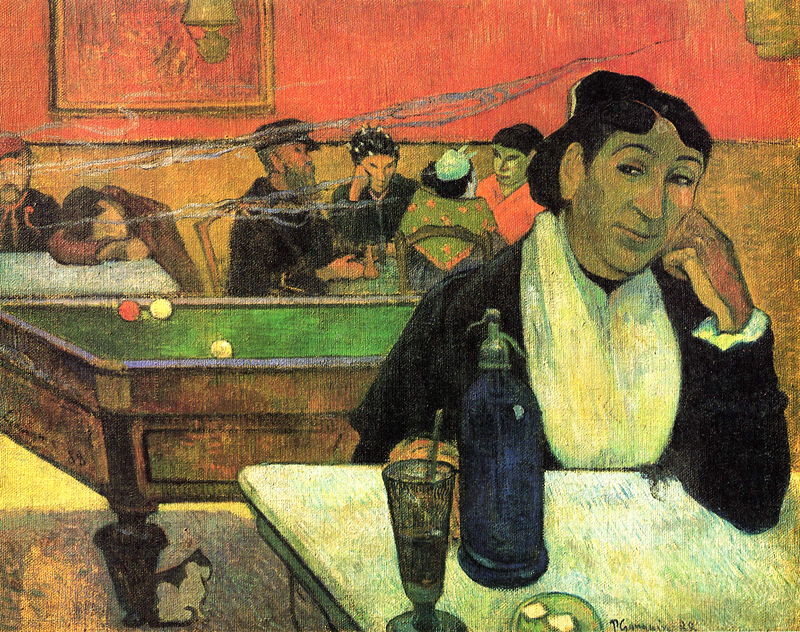

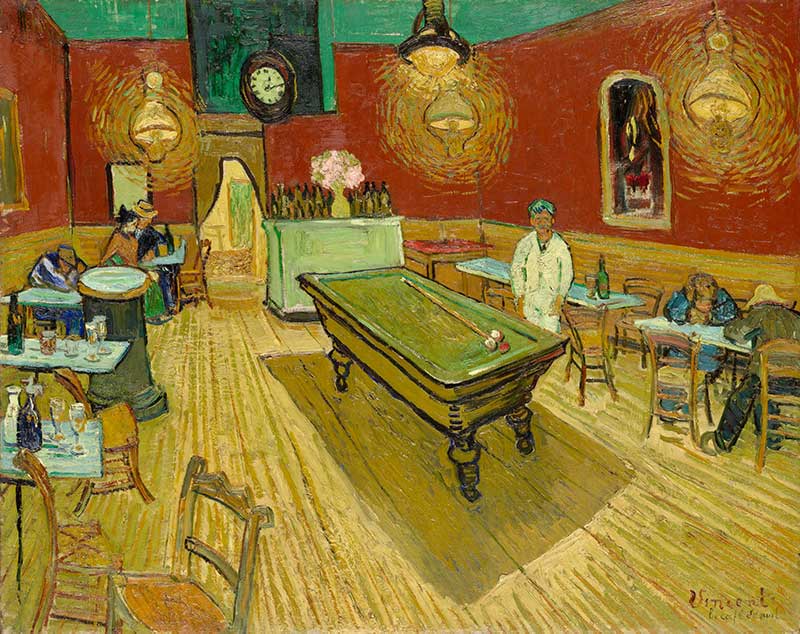

4. Night Cafe, Arles (1888)

In November 1888, Gauguin co-wrote a letter with Van Gogh to send to the artist Émile Bernard.

The letter described their experiences in the early days of living together in the Yellow House at Arles.

The letter also referenced Gauguin’s painting ‘Night Cafe, Arles’:

“Now something that will interest you – we’ve made some excursions in the brothels, and it’s likely that we’ll eventually go there often to work. ... At the moment Gauguin has a canvas in progress of the same night cafe that I also painted, but with figures seen in the brothels. It promises to become a beautiful thing.”

House-mates

The artists spent a total of 63 days living together, which resulted in a large collection of paintings: 36 for Van Gogh and 21 for Gauguin. In the same letter, Van Gogh also described Gauguin as

“an unspoiled creature with the instincts of a wild beast […] With Gauguin, blood and sex have the edge over ambition.”

Gauguin's version ....

In his version of the Night Cafe, Gauguin focusses on the figure of Madame Ginoux, whose portrait Van Gogh also painted. Behind her, men can be seen seated at tables with prostitutes, one figure lies with their head resting on their arm, slumped forward in their chair.

Differences in van Gogh's version

Unlike Van Gogh’s painting of the same Cafe, Gauguin’s work is thick with sexual references. Madame Ginoux wears a knowing expression on her face and a small cat seated beneath the billiards table acts as a symbol for sexuality and lust (just as in Manet's Olympia).

The flattened planes in this painting also echo Japanese wood block prints, as do the blank and largely featureless faces of the figures in the background.

Where is it now?

Gauguin's Night Cafe is now found in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Art in Moscow. Van Gogh's version is in Yale University's Art Gallery.

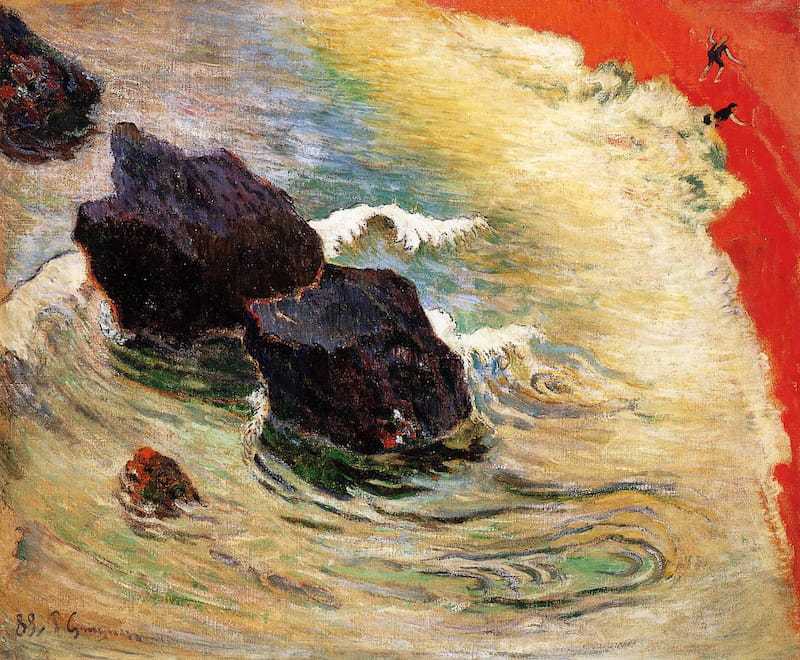

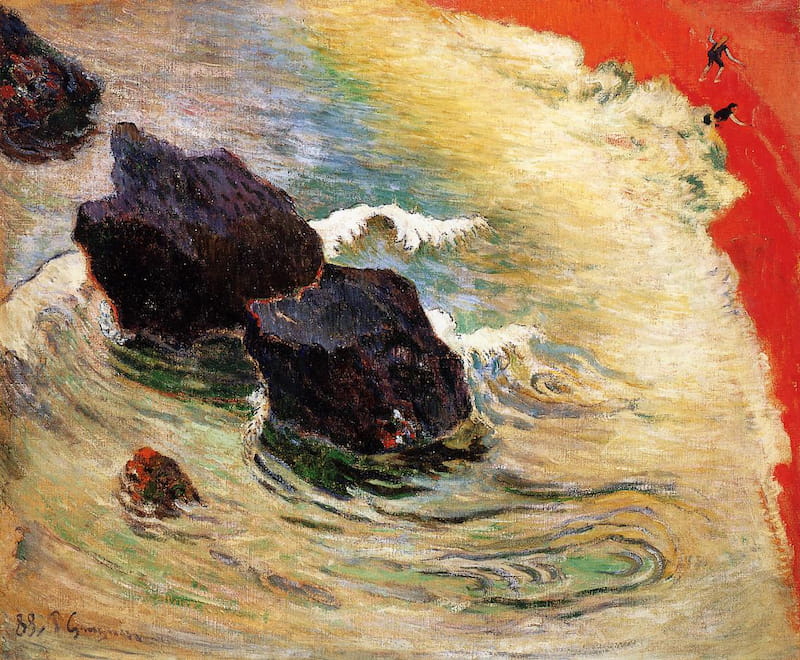

5. La Vague (1888)

Gauguin regularly chose to compose his landscapes using an elevated perspective, inspired by the Japanese prints that were enormously popular in France at this time.

In ‘La Vague’ or ‘The Wave’, this effect is extreme with the viewer looking down from an almost vertical height at the coastal scene below.

Gaugin's inspiration

In this painting, there are echoes of Hokusai’s famous woodcut titled ‘The Great Wave off Kanagawa’ (1830-32), which was already famous when Gauguin was painting. Art historians have speculated that Hokusai’s piece inspired the painting’s name.

Le Pouldu

Gauguin first conceived the idea for the piece during a visit to the small fishing village of Le Pouldu.

There he found a broad, steep cliff which provided a vantage point from which he could see the water below with a collection of massive black rocks. This location formed the starting point for his painting, which he then stylised with bold colours and dramatic imagery. He also added a third rock in the upper left of the composition to accentuate the diagonal lines.

Symbolism?

Critics have suggested that Gauguin’s composition is also symbolic, intended to represent the plunge into the inner recesses of one’s own psyche and emotions. There is an added sexual element to the piece in the form of two female bathers who are running from the waves.

What's up with that sand?

What is most striking about this piece is the intense vermillion-coloured sand which lends drama to the piece. The painting’s name at a Paris auction in 1891 was ‘La Vague (arc-en-ciel)’ meaning ‘The Wave (rainbow)’, referencing the range of colours included in the waves.

Here Gauguin interwove curves of pale violet, blue, green and yellow, using dynamic, humming brushstrokes that have similarities to Van Gogh’s work from this time. Though a very different work, check out the colours and brush strokes in the sky of van Gogh's Wheatfield with Cypresses:

Where is it now?

Alas, The Wave is held in a private collection having been bought by American banker David Rockefeller in 1966.

6. Vision After the Sermon (1888)

“I like living in Brittany; here I find a savage, primitive quality,” wrote Gauguin in February 1888.

In this piece, we see Gauguin go some way to expressing that quality on his canvas.

Gauguin had a strong desire to find a new kind of expression in painting and while in Pont-Aven in August 1888 he began to realise those aims.

Gauguin and Bernard

When Gauguin met fellow artist Emile Bernard, who was experimenting with a simplified type of painting, he was inspired to transform his art.

He began working on a highly personal form of painting that drew on primitivist principles. In his words:

“Art is an abstraction; as you dream amid nature, extrapolate art from it and concentrate on what you will create as a result."

What's going on?!

In this piece, the imaginations of a group of Breton women play out. Gauguin constructed the painting as though the women have just listened to a sermon on the story of Jacob wrestling with an angel from the Bible. Indeed, Jacob Wrestling with the Angel is an alternative name for the work.

This was Gauguin’s first true symbolist painting and it is dominated by the same brilliant vermillion hue seen in ‘La Vague’.

Breton women

Gauguin favoured Breton women in many of his artworks for what he perceived as their primitive nature, rooted in their connection to the earth. On the other hand, they remained largely unattainable to him due to their devout Catholic faith and this sexual tension felt by the artist is expressed in his art.

Writing to the painter Claude-Emil Schuffenecker in October 1888, Gauguin asserted:

“I wished to force myself into doing something other than what I know how to do. […] Clearly the path of symbolism is full of dangers, and I have not yet ventured more than the tip of my toe in that direction: but symbolism is fundamental to my nature, and one should always follow one’s temperament”.

Where is it now?

Vision After the Sermon is now found in Edinburgh's National Gallery.

7. Christ in the Garden of Olives (1889)

In a letter to Van Gogh, Gauguin described his latest painting:

“Blue-green sky in the west, all the trees bent in a purple mass, the earth is violet and Christ is dressed in a dark ochre attire, his hair vermillion. The canvas is not intended to be understood. I shall keep it for myself for a long time.”

The piece was ‘Christ in the Garden of Olives’.

Gauguin in 1889

During this period, Gauguin was at a particularly low point. He had failed to receive any financial support or praise for his work after participating in several exhibitions in Paris.

In a letter to Bernard, he wrote:

“My soul is far away and looks sadly into a black abyss that opens in front of me.”

From the midst of this disappointment and depression, Gauguin began to construct a persona for himself as “the chosen one” and “the saviour” of modern painting. He had an intense conviction that his art was “divine” and more righteous than that of other artists.

Self-portrait?

When he painted ‘Christ in the Garden of Olives’, Gauguin used his own features for Christ’s face. In doing so, he formed a parallel between his own suffering and the suffering of Christ after he was betrayed.

At the same time, the composition of the painting also has religious undertones. The tree trunk divides the piece into a diptych as one would expect to see as an altarpiece.

Interesting fact...

This was not the only time that Gauguin depicted himself as Christ. Keep reading for another example ...

... and Jerusalem

On the other hand, the painting does not feature the landscape of Jerusalem or even Brittany. Instead, it borrows from the landscape of Polynesia, like his painting ‘Where Do We Come From? Where Are We? Where Are We Going?’ which was painted later.

Reaction

The art critic Jules Huret described the painting after seeing it at an exhibition in 1891:

“I could see that his face showed terrible suffering but it was inadmissibly too ugly to be Christ's face. The beard seemed too red and why those greens, reds and harsh blues? And why those strange trees? What do those escaping people mean? From where did I get such a dispiriting impression of fear which sank to the very marrow of my bones?”

Where is it now?

If you still want to see it (!), Christ in the Garden of Olives is found in Florida's Norton Museum of Art.

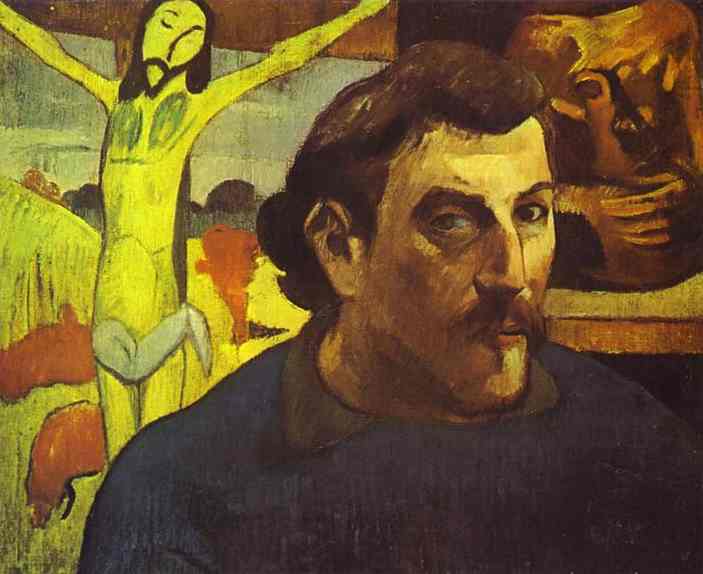

8. Self-Portrait with the Yellow Christ (1890/91)

This self-portrait was painted shortly before Gauguin’s departure to Tahiti for the first time.

Within the painting, we can see the artist ruminating on different parts of his personality through his own artworks.

Gauguin as Christ

Behind the figure’s torso, it is easy to recognise his painting ‘The Yellow Christ’ which was a self-portrait with suffering at its core. Gauguin painted himself as christ on the cross in intense yellow hues.

Interesting fact...

Gauguin was a narcissist, seemingly caring only about himself. The fact that he had the audacity regularly to depict himself as Christ tells you something about the size of his ego!

Reading the painting

To the right is his ‘Pot in the Form of a Grotesque Head’, another self-portrait, this time made from ceramics. As Gauguin described, this pot was the

“head of Gauguin the savage”.

What can be read from these two contrasting artworks is Gauguin’s complicated self-image: certainty that he was special; long suffering and despairing; and wild and ‘primitive’. In the centre, the artist looks out from the painting with a strong gaze representing the culmination of these aspects of his personality.

Where is it now?

Gauguin's Self-Portrait with the Yellow Christ is found in Paris' Musee d'Orsay.

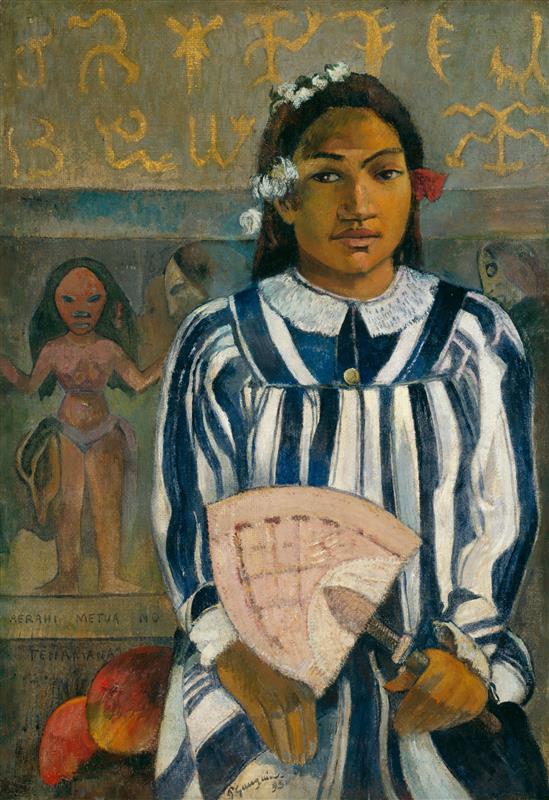

9. The Ancestors of Tehamana (1893)

In 1891, Gauguin arrived in Papeete, the capital of Tahiti.

Tahiti was a French colony and Gauguin - like many other French expats - married a local.

This was extremely controversial, on account of the fact that Gauguin's new wife - Tehamana - was only 13 years old. To make matters worse, the marriage was arranged by Gauguin's bride's family over the course of an afternoon.

In fact there were loads of further problems: Gauguin had abandoned a wife and five children in France, and was suffering from syphilis.

The painting

This portrait represents Gauguin’s attempts to translate what he found in Tahiti onto canvas. The piece is a jumble of different cultural references, from carved memory boards (rongo-rongo) originating on Easter Island to Japanese-inspired masks. At the centre of it all is Tehamana, the embodiment of the tangle of cultures that Gauguin constructed.

These elements would have served to intrigue Parisian viewers and so Gauguin employed exoticised imagery partly in order to sell his artworks back in France. This is just one of a wide range of paintings Gauguin produced during his stay in Tahiti where he fabricated a world for himself and his French audience, based on European expectations of far-away lands.

What's in a name?

The painting is called Merahi metua no Tehamana in Tahitian and either Tehamana Has Many Parents or The Ancestors of Tehamana in English.

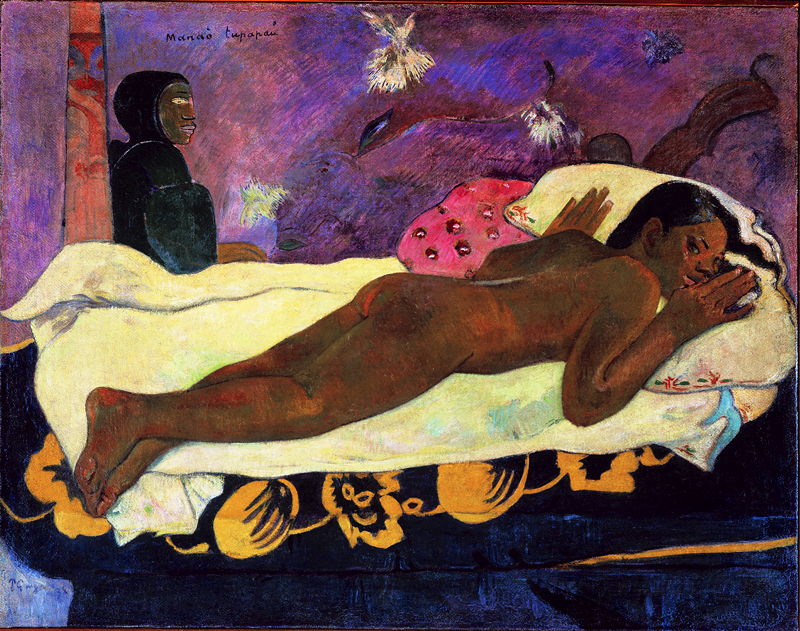

Spirit of the Dead Watching

Another painting Gauguin made of Tehamana is called Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892). Gauguin's wife is portrayed naked on a bed, looking apprehensively towards the viewer.

It is unclear what is making Tehamana nervous: her predatory older husband; or the Tahitian spirit in the background. Perhaps it was a bit of both.

Where is it now?

The Ancestors of Tehamana is now found at the Art Institute of Chicago, whilst Spirit of the Dead is found at the Albright Knox Art Gallery.

10. Where Do We Come From? Where Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897-98)

One of Gauguin’s most famous and distinctive paintings, ‘Where Do We Come From? Where Are We? Where Are We Going?’ is painted on a colossal scale.

Measuring 139 x 374 cm (54 x 147 inches), the canvas is the largest Gauguin painted in his career. He envisioned the piece as a mural, despite not having planned it for any particular setting.

Gauguin's method

In fact, Gauguin deliberately employed techniques to make the piece look more like a fresco. He used a rough burlap cloth as the canvas to give the painting a fresco-like texture.

He also painted the two upper corners yellow, to make it appear as though the “corners are spoiled with age” and the piece “is attached to a golden wall”. When he sent the piece to Paris, Gauguin specified how it should be framed:

“a plain strip of wood, 10 centimetres wide, and white-washed to resemble a mural”.

Gauguin's defining work?

Completed in just one month, the painting was intended by Gauguin to be a defining artistic statement following his move to Tahiti in 1895.

Writing to his friend, Daniel de Monfried, Gauguin said:

“I believe that this canvas not only surpasses all my preceding ones, but [also] that I shall never do anything better, or even like it.”

The artist also wrote to de Monfried explaining how he went to the mountains with the intention to commit suicide after completing the painting. Whether or not this is true is unclear.

As Gauguin was a storyteller, constructing and reconstructing the myths around his own artistic persona, it is highly likely that this event was fabricated. Nonetheless, it matches the themes of the painting, which can be read as a mediation on life, death and identity.

Where is it now?

Gauguin's work is now found in Boston's Museum of Fine Arts.

11. Learn more

Gauguin died in 1903 in Tahiti, five years after producing Where Do We Come From?

He died a pauper who was unappreciated in his lifetime. But his painting slowly started to gain popularity, largely as a result of the efforts of dealer Ambroise Vollard. And it in due course inspired Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

Gauguin was pretty clearly a bad man: he was a narcissist who abandoned his wife and five children in France to 'marry' a 13 year old in Tahiti. And this raises the question: can we divorce the art from the man?

Learn more about Gauguin on our Paul Gauguin biography page.