1. Christ in Limbo (1867)

In his early career, Cézanne was heavily inspired by the old masters.

He used dark colours, drawing on examples from Delacroix, Daumier and Courbet.

This particular piece was once part of a far larger composition that decorated the walls of Cézanne’s family home near Aix-en-Provence.

After the artist’s death, the murals were transposed onto canvas. Over time they were gradually split up and it is unclear how large the original piece would have been.

‘Christ in Limbo’ is evidence of Cézanne’s early interest in religious painting, drawing on Provençal traditions and classical religious imagery.

This painting is an interpretation of a work by Italian Renaissance painter Sebastiano del Piombo. At the same time, Cézanne utilised a bold palette of red, blue and white, set against darker and more monochromatic elements. He used broad brushstrokes and impasto to build up the shapes of the figures.

They stand out against the black background, creating a dramatic piece that shows Cézanne’s early preference for bold images.

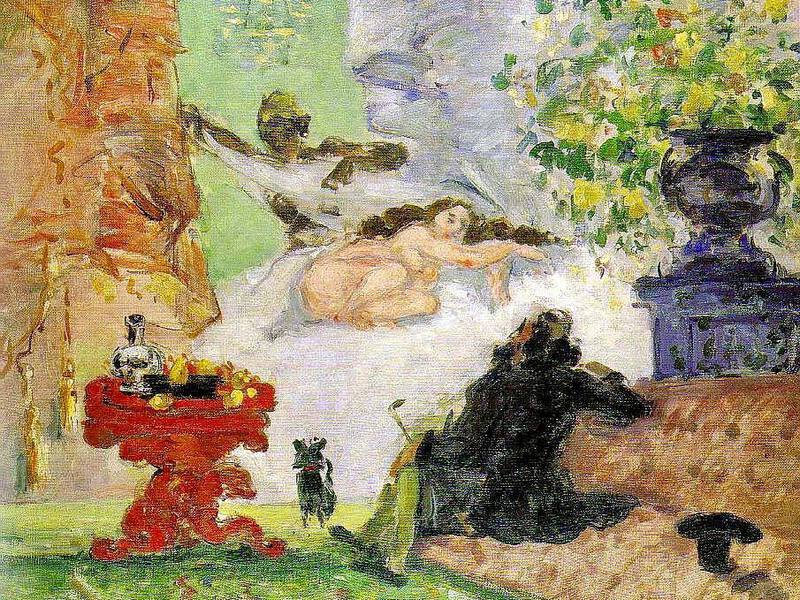

2. A Modern Olympia (1873-4)

Painting in response to Manet’s ‘Olympia’ (1863), Cézanne executed two versions of ‘Une Moderne Olympia’.

The earlier work from 1870 is now part of a private collection but the later painting, from 1873-74, is in the Musée d’Orsay. This later version is strikingly different to the earlier piece as Cézanne’s style shows a clear move towards impressionism.

Cezanne painted his second ‘A Modern Olympia’ while staying with Doctor Gachet, one of his earliest patrons, at Auvers-sur-Oise.

According to reports, Cézanne was motivated to revisit the subject during an intense discussion and he painted a quick sketch that was deliberately intended to be shocking to his companions.

The scene is theatrical: it is as though Olympia is an object on display, elevated above the client who is positioned as a spectator. This effect is heightened by the presence of a curtain and the dramatic pose of the servant.

Cézanne used bright, luminous colours to highlight the contrast between the nude woman and the dark clothes of the seated man and the black servant who has uncovered her body.

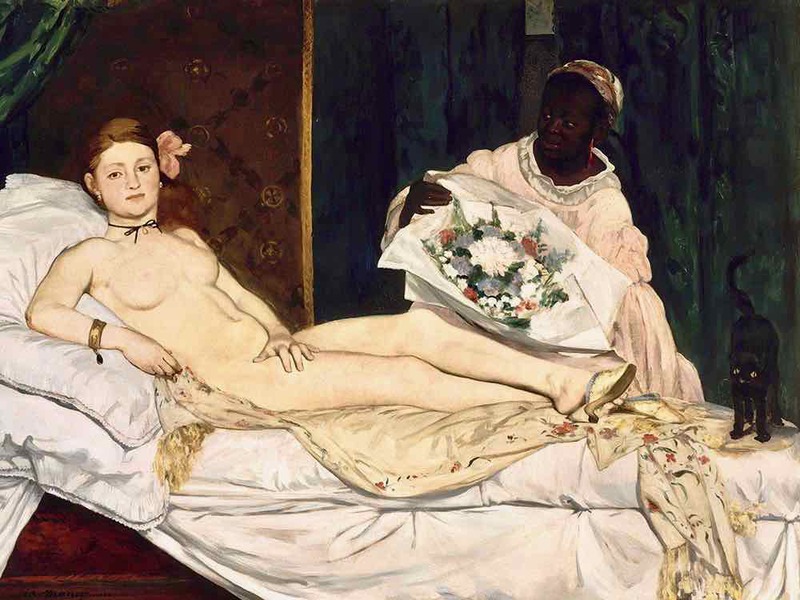

But his work is very different to Manet's Olympia, which created a huge scandal when shown at the Paris Salon in 1865.

According to Theodore Reff, this painting falls into the category of ironic adoration that reoccurred in Cézanne’s work, as also seen in works like ‘The Eternal Feminine’ from around 1877.

Indeed, the male figure in the painting bears a striking resemblance to Cézanne himself. This may have been part of a joke among his friends or could also be evidence of a more personal desire existing within Cézanne.

This version of ‘A Modern Olympia’ was shown at the First Impressionist Exhibition of 1874. Unsurprisingly, it evoked a dramatic response among the audience who placed great emphasis on propriety and classical art traditions.

As critic Marc de Montifaud described, the painting appeared

“like a voluptuous vision, this artificial corner of paradise has left even the most courageous gasping for breath […] and Mr Cézanne merely gives the impression of being a sort of madman, painting in a state of delirium tremens”.

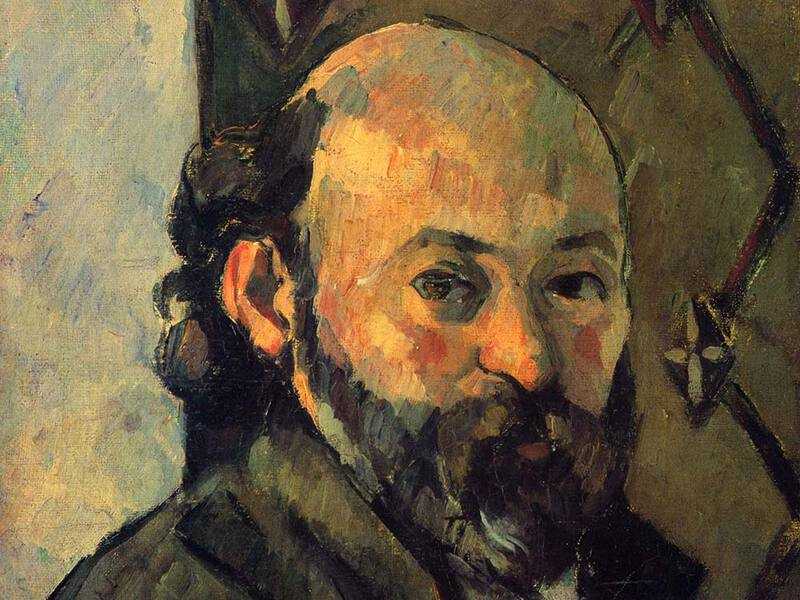

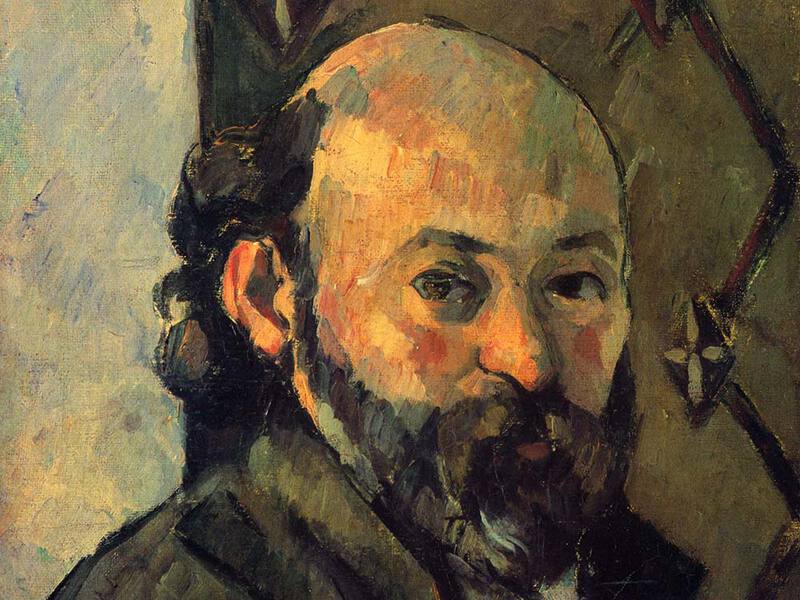

3. Self-Portrait (1880-81)

Painted in his apartment in Paris, ‘Self Portrait’ depicts the artist at around 40 years old.

This was a period of transition for Cézanne when he would leave Paris to spend more time in Provence. He also stopped exhibiting with the Impressionists after 1879.

Cézanne most likely painted the work while looking in the mirror. His face is expressionless, lit from the left side so that one side of his head is in shadow.

He used a palette of whites, reds and ochre to build up much of his features but swapped to bluish and green tones for the shadows and outlines on his ear and the top of his head.

The colours of the artist’s face are complimented by the olive greens of the wallpaper behind him. The repeating pattern of the wallpaper helps to integrate the self portrait in its surroundings.

The diagonal lines emphasise the curve of his cranium and his pale head and face while the diamond-shaped motif in the pattern mimics the shape of his ear and right eye.

Cézanne painted a number of self portraits throughout his career. In this piece, he appears to stare out at the viewer and yet as Hugh J. Silverman describes, the viewer is

“duped into believing that a staring match is underway is in fact an intruder. Cézanne is simply looking at himself in the mirror. […] Cézanne’s visibility is traced in the visible of the self-portrait producing a new visibility as it is seen by a viewer.”

His self portraits act as a record of his changing self image throughout his career.

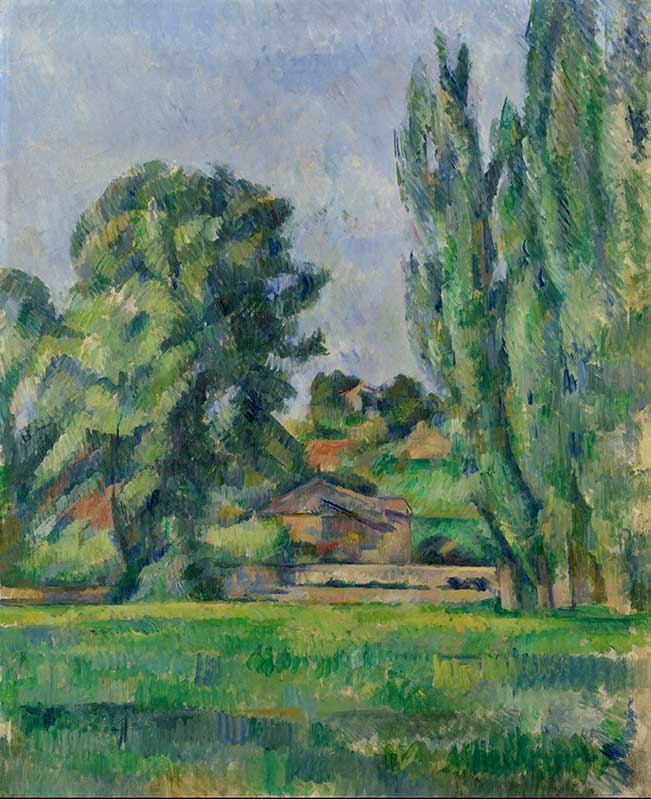

4. Landscape with Poplars (1885-7)

Throughout his career, Cézanne returned regularly to the landscape around Provence in his painting.

He spent much of his time outside Paris and was constantly drawn back to his home region.

‘Landscape with Poplars’ is one example of his works from the South of France, depicting a lush green landscape in the summer.

Drawing on the Impressionist technique of using bold colours in landscape paintings, Cézanne enjoyed using building up his composition with a palette of rich colours.

There are some key differences between Cézanne’s style and the work of other Impressionist landscapists like Claude Monet and Alfred Sisley, however.

Notably, he did not seek to capture the transitory effects of the atmospheric conditions. The aim was not to portray the unique weather conditions or subtlety of the natural light.

Instead, Cézanne used broad brushstrokes to build up the scene almost like a patchwork. He laid down parallel brushstrokes to denote form in the landscape, then using looser strokes to build up the meadow in the foreground. He stripped away unnecessary details, seeking only to represent the simplified forms of nature in this piece.

Cézanne repeatedly stressed the importance of painting from nature. He emphasised his commitment to painting sensations and it was through colour relationships that he painted the "fundamental character” of his subjects.

5. Boy in a Red Waistcoat (1888-90)

One of the most influential paintings in Cézanne’s oeuvre, ‘Boy in a Red Waistcoat’ is an important forebear of later Fauvist and Cubist works.

To capture the image of the boy, Cézanne used a series of blocks of colour. He essentialised the different elements in the piece, simplifying the forms down into shapes.

The effect can be seen clearly in the way the patterned drapes in the background are painted onto the canvas. Rather than a detailed, delicate image, the artist used a series of arcs and angles to build up the impression of the fabric in a flattened and fractured way.

When compared with the Cubist works of Braque and Picasso, the similarities become especially apparent.

At the same time, Cézanne referenced classical portraiture in the pose of the figure, with one hand resting elegantly on his hip. The model, Michelangelo di Rosa, is dressed as a Romantic era Italian peasant with a wide-brimmed hat, waistcoat and tie.

Cézanne used a wide range of tones to build up Di Rosa’s face and clothes, contrasting with the bright red waistcoat.

This painting is one of a series of four works, all depicting Di Rosa in varying poses. One of these paintings was purchased by Monet who reportedly described the piece as the best picture he owned.

6. Still Life with Apples and Pears (1891-92)

Still-life paintings became a more prominent feature of Cézanne’s work from the 1880s onwards.

His still-lifes are recognised as some of his most important artistic achievements thanks to their influence on the stylistic developments of early 20th century art.

Cézanne encouraged a resurgence in still-life painting, infusing his works with emotion and intensity that is more familiar in portraiture than still-lifes.

What is notable about Cézanne’s still-life works is his use of contrast. He experimented with building a sense of space and volume when presenting three-dimensional forms on a two-dimensional surface.

The harsh horizontal lines of the table top and wallpaper, as well as the vertical lines of the table legs and door frame provide a strong contrast to the rounded shapes of the apples and plates. Similarly, the composition is made more dynamic thanks to the cropping technique, which cuts off the piece of fruit on the left.

In fact, Cézanne painted still-lifes throughout his career but it was in his later years that he began to devote more energy to the genre. His mature paintings are characterised by their modernity and rigour, slowly becoming more complex over time.

As well as painting still-lifes in oils, as in ‘Still Life with Apples and Pears’, Cézanne also produced a series of watercolours.

As Richard Kendall described:

“By this stage in his career, the still-life had taken on a special significance for [Cézanne], and he was to become one of the most original and dedicated exponents of the form. Far from being just a pretext for picture-making, the groups of apples, pears, cherries or flowers were for Cézanne as much a part of nature’s extravagant beauty as the trees and hillsides of Provence, and as likely to produce his ‘vibrating sensations’ as the landscape itself.”

Cézanne frequently returned to apples as a way to understand nature and represent it on his canvas. He is quoted as saying

“With an apple I want to astonish Paris”.

7. The Grounds of the Château Noir (1900-04)

Cézanne rented a room at The Château Noir between 1897 and 1902.

Though he later moved away, he continued to return to the house to paint until his death in 1906.

Using a rented car, he would drive to the Château and draw inspiration from the dramatic grounds surrounding the grand property.

This particular painting is notable for its overlapping faceted brushstrokes that give the painting a sculptural effect. Combined with a dark colour palette of green, browns and greys, this painting is evidence of Cézanne’s later impact on Cubism in the 20th century.

Picasso and Braque would draw on his stylistic experiments in paintings such as ‘The Grounds of the Château Noir’ in the development of their new school.

The dark palette, broken only by a small area of orange that serves as the focal point in the painting, is evidence of Cézanne’s preference for harsher landscapes in his later life. ‘The Grounds of the Château Noir’ contrasts heavily with his sun-filled landscapes of the previous decade, painted in luminous colours.

Instead, his palette in this piece references his earliest works and the drama and darkness within them. It is possible that this reflected Cézanne’s own mood at the time: sombre and claustrophobic.

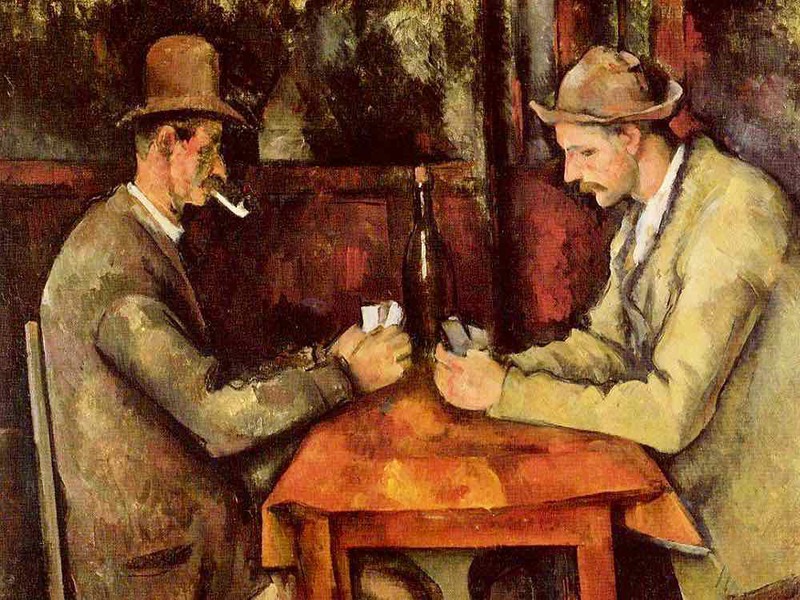

8. The Card Players (1890-92)

One of Cézanne’s most famous works, ‘The Card Players’ was painted late in the artist’s life, when he was already in his fifties.

In total, Cezanne painted five pieces in the series all set in a mostly sparse space with rural labourers seated around a table playing cards.

This piece is one of a number of Cézanne’s works featuring Provençal labourers, which stand in stark contrast to Impressionist depictions of the fashionable upper classes at leisure.

Caillebotte also painted ‘Game of Bezique’ (1881) but his figures are smartly dressed in a richly decorated drawing room. In contrast, Cézanne’s characters are quiet, understated and familiar, passing the time in a very simple room.

In painting this subject, Cézanne was also referencing the paintings of Caravaggio and Chardin, as well as the works of Meissonier and Daumier.

Throughout the series, Cézanne uses a tricolour. In the below work, he chooses red, blue and white. The colours are picked up in small details, in the blues of the figures’ clothes, the colours on the playing cards, and the rosy reds of their cheeks and knuckles.

This painting was sold to Ambroise Vollard for 250 francs who then sold it on to a private collector for 4,500 francs in 1900.

Compare the 2002 sale of one of the Card Players for a world-record $259 million.

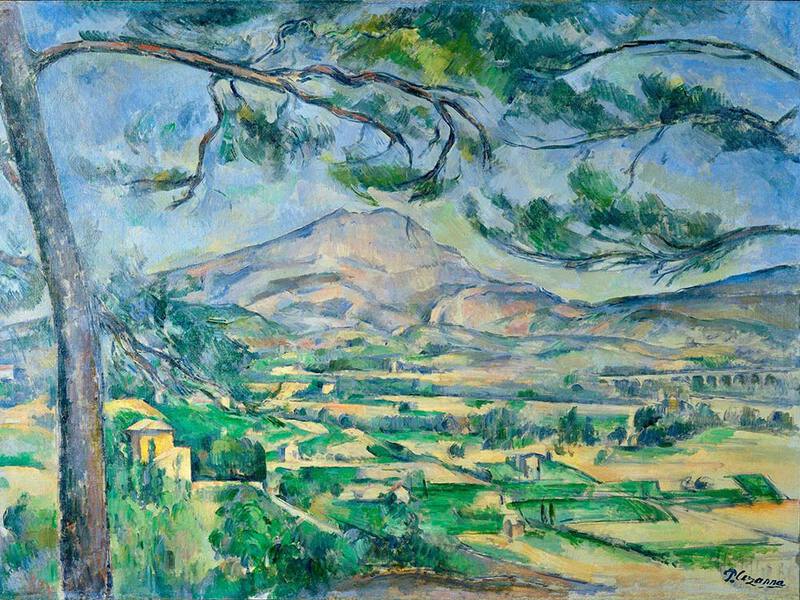

9. Mont Saint-Victoire

The Montagne Saint-Victoire became a frequent subject in Cézanne’s art in the latter years of his life.

After the death of his mother in 1894, Cézanne left Paris to return to Aix-en-Provence.

He painted the mountain from a number of different views, including the terrace of the Château Noir, the quarry in Bibemus, at his sister’s house Montbriand, from the north of Aix and more.

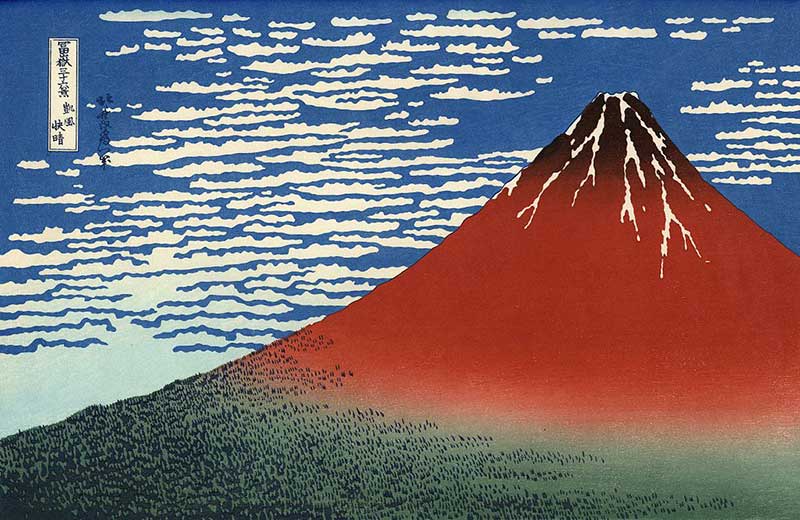

In Cézanne’s series of the Montagne Saint-Victoire, he captured the mountain at different times of the day and in different seasons. The simplification of form and his use of bright colours may have been influenced by Japanese art, especially the views of Mount Fuji by Hiroshige and Hokusai.

As Hidemichi Tanaka points out, Cézanne painted 36 oil paintings of the mountain in total, coinciding with the 36 views of Mount Fuji by Hokusai. Similarly, he adopted some of the compositional devices of Japanese artist Ukiyo-e in his work.

For almost a decade, Cézanne returned to the “imperious and melancholy” mountain, as he once described it in his youth. Even in 1906, the artist still made a trip to the mountain to paint, getting caught in a storm.

He died not long after, fulfilling the promise he made in a letter to Emile Bernard,

“I have sworn to die while painting, rather than sinking into the degrading senility that threatens old men”.

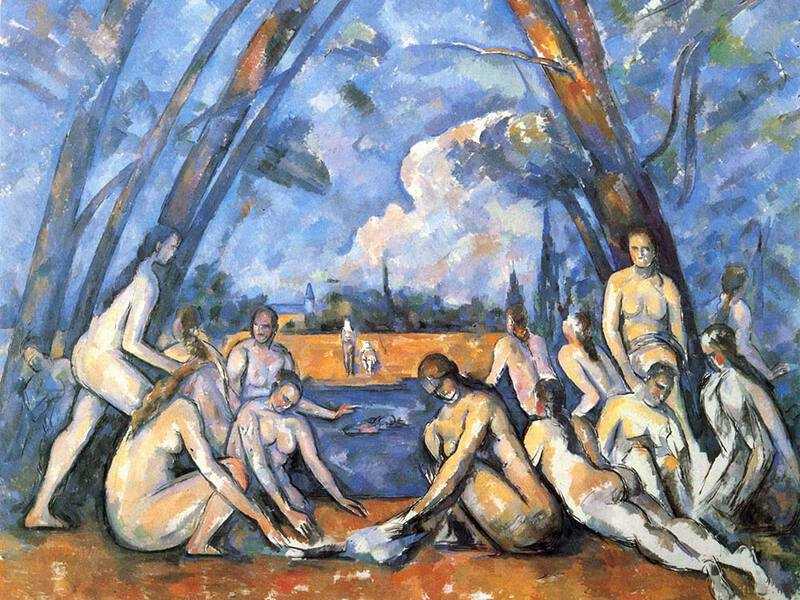

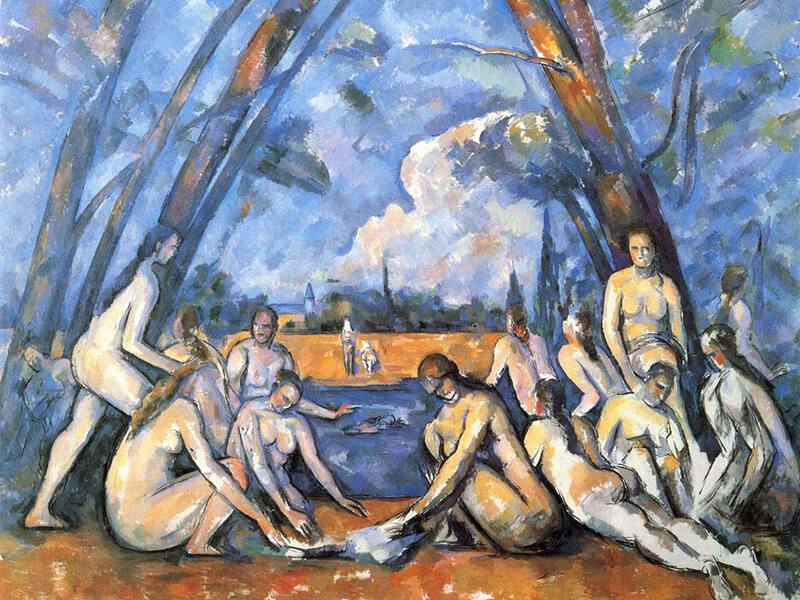

10. Les Grandes Baigneuses (1894-1905)

In the final decade of his life, Cézanne worked on three paintings of bathers.

It is difficult to pinpoint when exactly each piece was painted and it is possible that he worked on them all simultaneously. Indeed, every version shows evidence of having been revisited and reworked.

These impressive paintings, the largest of his career, can be read as a final artistic statement by Cézanne. During his life he painted approximately 200 works of male and female bathers, all nude and positioned either alone or in groups.

Tones

The above painting is made up of a rich palette of blue tones, denoting the landscape, shadows and skin of the figures. These blue touches are contrasted by warmer orange tones within the painting. The deep blue of the sky makes it appear as dense as the figures.

The resulting effect is an intoxicating painting that is one of Cézanne’s most memorable.

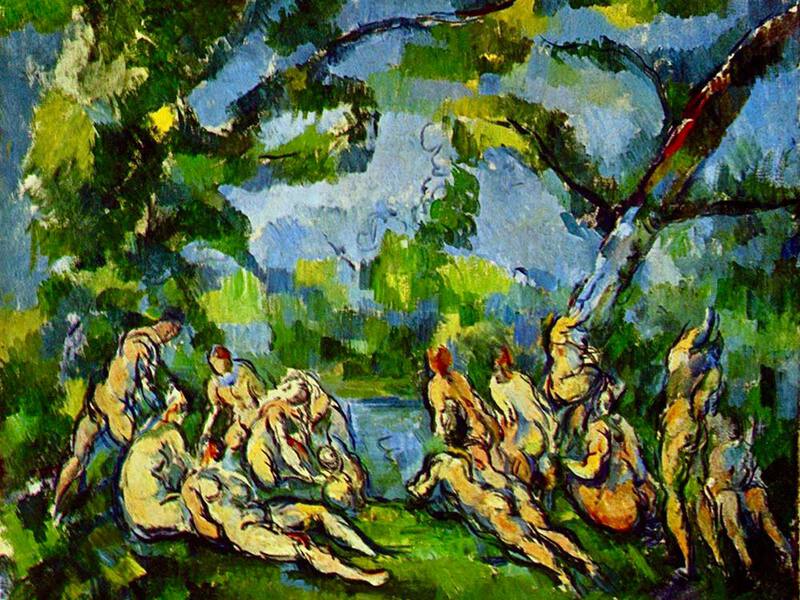

Here's another version of Cezanne's Bathers, this time using green as the predominant colour.

Cubism

Looking at ‘Les Grandes Baigneuses’ it is easy to see the influence that the piece had on 20th century modern art, especially Cubism (of which Picasso was the most famous exponent). The figures are painted as blocks in forms that only roughly reference the human body.

They are positioned in diagonals, grouped into a single mass. At the same time, the space is flattened and simplified so that the bodies appear as though they are part of the landscape.

As he once wrote to his protégé, Emile Bernard, one must

“treat nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone”.