1. Cezanne's Childhood in Aix

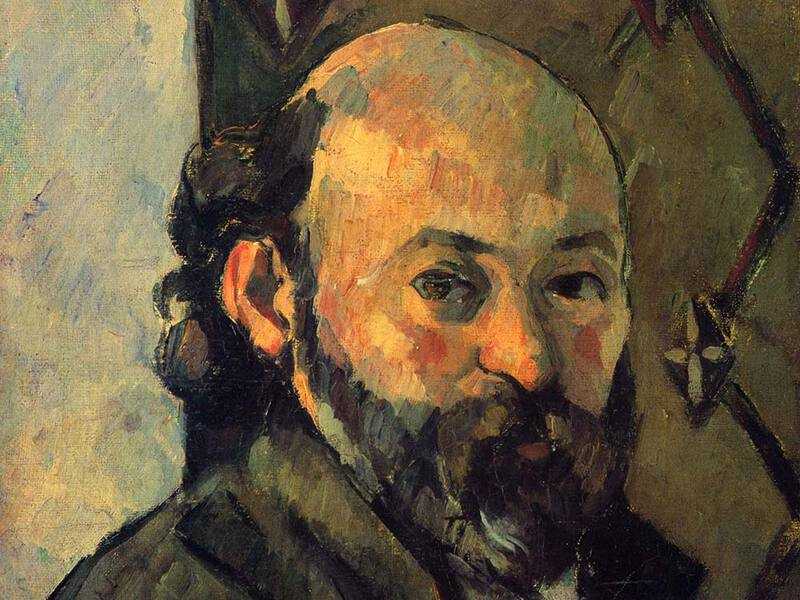

Paul Cezanne was born in Aix-en-Provence on 19 January 1839.

In Paris, he was immediately recognisable as being from Provence.

Cezanne had the lilting accent of the Midi region and he cut a curious figure in the studio of ‘Pere’ Suisse, where he first met Camille Pissarro.

His reputation was such that he was known as the ‘strange Provençal’ and Pissarro first made a special visit to the studio in the morning to meet him, as that was the only time he would attend the drawing classes.

Cezanne Senior

Cézanne grew up at 14 rue Mertheron in Aix-en-Provence, situated at the foot of Mont Saint-Victorie. His father was an extremely successful businessman, working as a hat salesman and gradually building up his fortune to the extent that he was able to purchase Aix’s only bank.

Shortly before Cézanne left Provence to go to Paris, his father bought an enormous and largely derelict mansion outside of Aix (called the Jas de Bouffan). Formerly the residence of the governor of Provence, the property was a symbol of the family’s status in the community.

Crucially, it was also a space in which Cézanne felt inspired to paint and he did so often, using the views around the house as his subjects.

Depression

As a child and young man, Cézanne struggled frequently with depression. After moving to Paris in 1861, he told his close childhood friend, Émile Zola:

“I thought when I left Aix, I would leave behind the depression that I can’t shake off, but all I’ve really done is change places. I’m still depressed. I’ve just left my parents, my friends and some of my routines, that’s all.”

Provencal identity

In his conversations with Zola in the early years of living in Paris, one can also see his continued loyalty to his Provençal identity. After admiring the work of the masters in the Louvre, he exclaimed how he had never seen works of art in such variety and number,

“but don't think that means I’m turning into a Parisian.”

He was distrustful of Paris and Parisian women especially. He also suffered from a deep sense of inadequacy, frequently destroying his canvasses when he didn’t like them.

Back and forth

By the end of his first year in Paris, he had decided to return to Aix, and he took a job in the bank owned by his father. However, the move was not permanent and he soon returned to Paris.

For the next two decades or so, Cézanne returned frequently to Aix, sometimes visiting his parents for short periods and other times moving back to the area for a longer time. In a letter to his parents in 1874, he explains some of the attraction,

“200 francs a month […] will enable me to make a real visit to Aix, and it would make me extremely happy to work in the Midi where the scenery offers so many opportunities for my painting.”

He continued to split his time between Paris and Provence until his father’s death in 1886.

2. Cezanne returns to Aix for good

At the age of 47, Cézanne decided to return permanently to Aix after many years of living in Paris.

As a result of his father’s death, Cézanne had inherited a significant fortune and the family home in Aix. This gave him the financial stability he needed in order to break away from the art market in Paris and a strong incentive to return to his birthplace.

What drew Cézanne to Aix was not just his familial connection to the area, however. After all, many artists chose to remain in Paris despite having their roots elsewhere. Instead, Cézanne’s motivations were part of a deeper, spiritually significant move that would come to define the latter period of his life and his career.

Attachment to Provence

His feelings of attachment to Provence can be seen in many letters he wrote to friends. To the poet Joachim Gasquet in 1896 he said:

“I recommend myself to you and your good thoughts, so that the links that keep me attached to our native soil, so vibrant, so harsh and so reverberant with light that your eyes squint and your vessels of sensation are enchanted, will never break and set me loose as it were from the land where I felt, even without realising it, so much.”

Le Jas de Bouffan

The manor he had inherited was ‘Le Jas de Bouffan’, or ‘Place of High Winds’, set in 37 acres of parkland and with an adjoining farm. The 18th century manor house was about half a mile outside of Aix, with avenues of chestnut trees and olive trees. The grounds also had impressive views of Mont Sainte-Victoire which provided ample subject matter for Cézanne. He painted the mountain over 87 times through his life.

There are 37 oils and 16 watercolours of the Jas de Bouffan itself. ‘The Neighbourhood of Jas de Bouffan’ from 1885-87 is just one example of Cézanne’s paintings made in and around the family home, showing the view from the estate on a warm, cloudless day. In letters he spoke of his “enormous affection for the contours of my countryside.”

For Cézanne, Aix represented a rural paradise, away from the increasing industrialisation of France’s capital city. Like so many before and after him, Cézanne sought out a ‘simpler’ life in the countryside. This was coupled with an ideological vision of Aix as his natural homeland. As a result, he framed his move as a ‘homecoming’ rather than as a departure from Paris.

3. Provence in Cezanne's Art

Cézanne’s art reflects the strong attachment he had to Provence.

The people, the culture and the landscape, and even the climate take on a deep significance in his work. It was also the place in which he felt most able to pursue painting. These sentiments are revealed in a letter he wrote to Monet in July 1895, after a brief stay in Paris:

“I have ended up back in Midi, which I should perhaps should never have left, to hurl myself into the chimerical pursuit of art.”

Despite his earlier commitment to Impressionism and the progressive aims of the movement, he gradually retreated back to Aix both geographically and artistically. Cézanne chose to adhere to the vision of Provence as a rustic, rural landscape, untouched by modernisation. In doing so, he followed the aesthetic ideals that were in fashion during the 19th century.

Back to Nature

As in Brittany, Provençal painters ignored the industrialisation that was evident in the landscape. Instead, they referred to the visual culture that had come before them. Thus, avant-garde painters chose to depict Provence as a region of pristine and rough landscapes.

The Mediterranean was populated only by small, picturesque fishing boats and sleepy villages. The peasants also remained unchanged by modernisation and the recent tourism boom in the region since the laying down of new train lines. Instead, in the paintings from the time, they continue to tend the land and gather for traditional dances.

This naturalistic dream created an image of Provence as static and eternal. Artists chose scenes that depicted an idealistic vision of the past, regardless of the modernisation taking place around them. This dominant habit meant that most painters entirely ignored the realities of the 19th century and they sold this fiction to the Parisian art market.

Critics

Scholars and art critics praised the work of artists who captured idyllic, pastoral scenes and local customs and traditions. Parisians were charmed by the innocence and zest of these provincial paintings, the epitome of “Southern verve”.

One critic, Georges Lafenestre provides a sense of the general sentiments at this time, commending the

“remarkable displays of their sun-drenched land […] One needs a lot of subtlety in the eyes and delicacy in the brush in order to extract the luminous harmony characteristic of these rocky and dry landscapes”.

Many of the Impressionists were not exempt from this myth-making in rural France in the 19th century. Renoir, Pissarro and Van Gogh also painted their own versions of untouched and unchanged landscapes. There was a significant market for Provençal landscapes and artists keen to take advantage of it.

In the case of Cézanne, he was captivated by a nostalgia for simpler times and so, in his art, he reinforced the cultural stereotypes of Provence. This is evident in both his subjects and his style. In paintings like ‘Mont Sainte-Victoire and the Viaduct of the Arc River Valley’ (1882-85) and ‘The Brook’ (1900), as well as many more, it is possible to read the efforts of Cézanne to capture the “the boundless things of nature, [which] attract me and give me the chance to look with pleasure.”

Despite spending much of his childhood in the town of Aix-en-Provence, he never painted the town itself. He deliberately turned away from any reference to urbanisation. In this sense, he ignored one of the primary aims of the Impressionist movement.

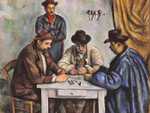

Card Players

Some of Cézanne’s most powerful and iconic paintings feature peasants from around Aix. His series of card players and pipe smokers from the 1890s are painted in different sizes, depicting real men from the farm on his estate. In these works, he sought to capture the essence of the workers, sun-beaten and steadfast. He later described his attraction to these subjects,

“I love above all else the appearance of people who have grown old without breaking with old customs.”

In his still-life works, as well as his landscapes, Cézanne refers to the influence of the Provence. Writing from Aix in 1886, he said,

“When I use paint to outline the skin of a beautiful peach, or the melancholy of an old apple, I catch a glimpse, in their reflections [...] their love of sun; their memories of dew and freshness.” In his work he wished to “become classical again, through nature.”

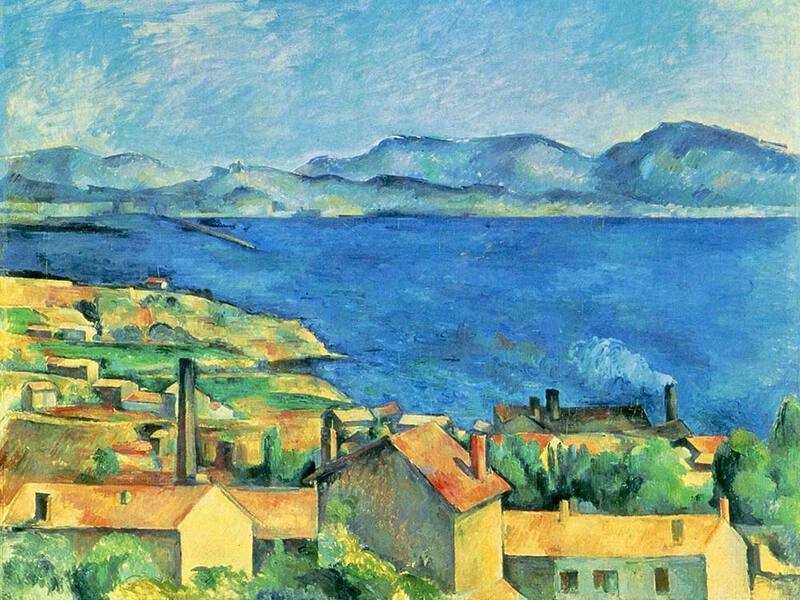

L'Estaque

Though this stylistic move began in earnest when he moved permanently to Aix in the 1880s, it was formulated gradually over the years. Whilst staying in L’Estaque in 1876, for instance, Cézanne wrote to Pissarro saying,

“I’ve begun two small subjects showing the sea […] It’s like a playing card. Red roofs against the blue sea […] The sun here is so vivid that it seems to me that objects are always outlines, not only white or black, but blue, red, brown, violet.”

Art historians have pointed towards the reference to playing cards as evidence of Cézanne’s interest in Provence’s cultural revival. Playing cards were a traditional craft closely associated with the Provence region.

Similarly, his description of primary colours points towards a simplified regional aesthetic that Cézanne sought to reference in his artworks, moving away from the Impressionist aims of representing colours as they appear in nature. These references hint at the direction his work would take in his later career and where later movements like Fauvism and Cubism would draw their inspiration from.

Conclusions

The ties that bound Cézanne to Aix shaped his career. From the draw of his family to his love of the landscape and the wider cultural revival of the region, Cézanne was a Provençal painter first and foremost. Though he was a key member of the Impressionist movement, he ultimately retreated to Aix in his art, choosing to live out the remainder of his life in the place where he felt most at home. In his later artworks, one can read his desire to fix his homeland into his own image of perfection, unchanging and unmodernised for eternity.

4. Cezanne and Politics

Cézanne’s decision to move permanently to Aix coincided with a wider political shift that saw the burgeoning of regional movements under the Third Republic from the mid-1880s onwards.

The people of Provence and many other regions of France reacted against what they say as the homogenising force of Paris and urban culture. They sought to preserve regional identities and as a result, this was a period of revival for traditional cultures, regional customs, languages and art.

Provincial patriotism

At the same time, the Third Republic passed laws in an attempt to reduce regional identities and create a sense of cultural cohesion throughout France. Hence, in the Midi, popular regional festivals like Bullfighting were banned and schools were forbidden to teach local dialects. This was an attempt to increase nationalism rather than regionalism throughout France.

The discourse surrounding rural France largely framed these regions as colonies under the colonial power of Paris. This is evident from writing, such as the historian Hippolyte Taine who wrote in 1863-65,

“The provinces are another France under the protectorate of Paris, which civilises them and emancipates them from afar by way of its travelling employees, its mobile garrisons, its colonies of civil servants, its newspapers, and a little bit by its books.”

In this context, provincial patriotism became a strong identifier of regions like Provence. In the Midi, bullfighting continued throughout the 1890s, despite the laws against it. Towns established themselves as cultural centres to challenge the power of Paris. Regional associations of writers and poets were also instrumental in fostering a sense of regional pride.

The Provencal intelligentsia

This provincial patriotism was a strong cultural driver behind Cézanne’s return to Aix. Indeed, many of Cézanne’s childhood friends were part of the cultural reimagining of Provence that took place during the mid-1800s. Scientists, poets, ethnographers, art historians and journalists all formed part of a tightly knit Provençal intelligentsia that was determined to capture and protect the essence of Provence.

Edmond Jalous, a friend of Cézanne who also lived in Aix attributed Provence’s newfound energy and patriotism to the freedom they had found after years of centralisation. He wrote:

“At this moment, when we witness the reemergence of the French provinces, it is not a bad idea to remind [ourselves] that they have not been as dead as people say, but, instead, that Paris and excessive State centralisation have ignored them as a rule. It is true that the concurrence of men […] has a prodigious character that cannot be accidental.”

His friend and later biographer, Joachim Gasquet also formulated his own cultural plan for Provence’s intellectual class:

“What we want is the full blossoming of the individual within the city, of the city within the province, of the province within the nation, of the motherland finally in a kind of federalist state.”

Gasquet formed an important role in bringing together the intellectual force of Aix.

It was in this energised cultural space that Cézanne found himself, at a moment when pride in Provence was burgeoning. Consequently, Cézanne’s return to Aix was both personal and political.