1. The development of Degas’ blindness

Degas began to lose his eyesight when he was still a young man as a result of a genetic condition.

In his twenties and thirties, he found his sight worsening dramatically and by the early 1870s, he was almost completely blind.

It is difficult to gauge the exact timeline of changes to Degas’ vision but we have strong evidence from his writing, letters and comments from friends and acquaintances that the condition got worse gradually. Over time, his art also changed to reflect his altered vision and sense of perception.

Initial problems

Degas first began to notice changes to his eyesight when he was as young as 19, making two references to his difficulties in his travel journals.

Indeed, the majority of the drawings from his sketchbooks from the late 1850s are of subjects close up, possibly indicating early onset of the myopia that affected him in later life.

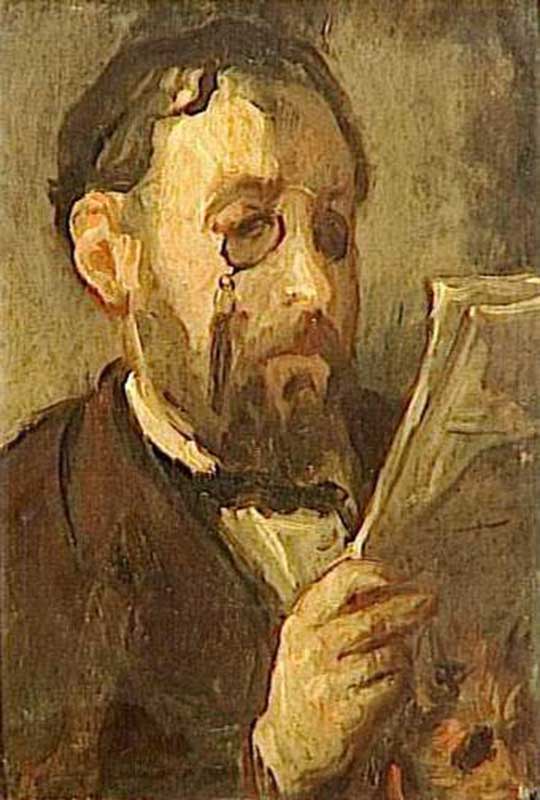

Self-portraits from early in his career also suggest that Degas struggled with his eyesight. Degas often emphasised his drooping eyelids and asymmetrical eyes.

One of the characteristics of the retinal condition Degas suffered from is slightly elongated eyeballs, which may account for this feature of his self-portraits.

The fear of impending blindness

From the 1870s onwards, there is much stronger evidence that Degas was starting to fear impending blindness.

He quickly lost his sight in one eye so that he largely relied on monocular vision for the majority of his life. Around this time, he began seeing specialists and his work also becomes increasingly preoccupied with subjects related to sight.

Two history paintings from this period are directly linked to the so-called ‘act of looking’, both ‘King Candaules’ and ‘The Daughter of Jeptha’ tell stories in which characters die because of sight and seeing.

Degas' works of Cassatt

Similarly, a large collection of the figure paintings he produced at this time involve the act of looking.

This includes numerous works of Mary Cassatt, studying a painting or a bonnet for instance, as well as subjects with spectacles and lenses, and a series of drawings and paintings featuring a woman starting out at the viewer through a pair of binoculars.

In these works, it is possible to track Degas’ own fascination with sight and seeing. It is also at this time that he began to express his concerns about his eyesight.

Target Practice ...

When he was enlisted into the National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War, Degas noted that he was unable to see out of his right eye. Paul Valery wrote that when he was

“sent to Vincennes for rifle practice, he discovered that he could not see the target with his right eye. It was confirmed that this eye was almost useless, a fact which he blamed (I heard all this from his own lips) on a damp attic which for a long time had been his bedroom.”

Over time, it became uncomfortable for Degas to be out of doors so he increasingly retreated inside. We also know that he had a blind spot in his right eye that prevented him from seeing anything in one area. He admitted that painting became an “exercise in circumvention” as a result of this impairment.

Writing to a friend after his return from the US, Degas confessed

“This infirmity of sight has hit me hard. My right eye is permanently damaged. I expect to remain in the ranks of the infirm until I pass into the ranks of the blind.”

2. Seeking treatment

Coming from a wealthy family, Degas had the financial means to seek out expert help for his failing eyesight.

He consulted a number of ophthalmologists in the hopes of alleviating the condition.

All sorts of treatments ...

Some of the treatments prescribed included bed rest, use of a magnifier and various pharmaceutical interventions such as “water for the eyes”, as Degas recorded in his notebook.

Between 1872 and 1873, Degas recorded the address of Dr Charles Abadie, an “oculist on behalf of Manet, 51 rue St Andri des Arts de Courcy” in his notes, suggesting that Edouard Manet had recommended him to a specialist.

Abadie was a prestigious ophthalmologist and also an art collector, In 1874, Degas also referred to treatment by an oculist in a letter.

Glasses?

Interestingly, Degas opted not to wear glasses for much of his life, despite the impact that it could have had on his ability to see the world.

From 1891, Degas began seeing Dr Edmund Landolt, founder of the French Ophthalmological Society. Landolt had treated other artists, most notably Degas’ close friend Mary Cassatt. It may have been on her advice that he began seeing this particular specialist.

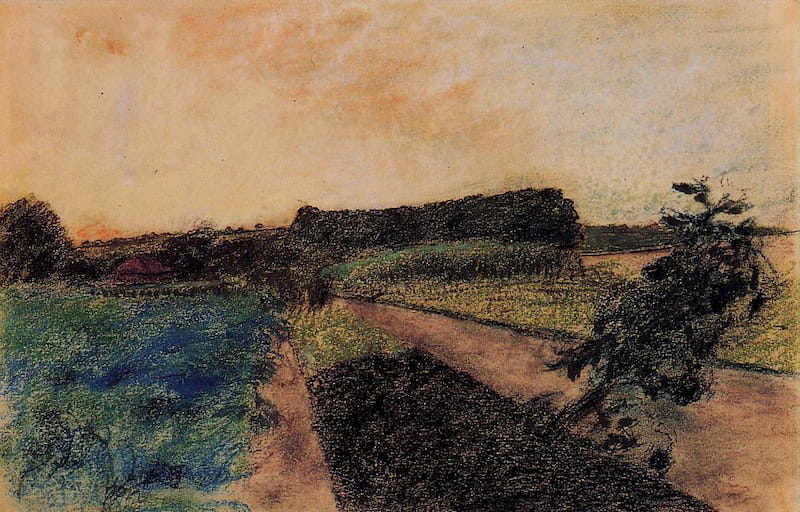

Daniel Halévy, a historian and friend of Degas, noted in his diary a discussion between himself and the artist in September 1892. Degas was discussing a series of landscapes he had recently completed, saying that he

“... stood at the doors of railway carriages and looked around vaguely. That gave me the idea of doing some landscapes. There are 21 of them.”

Halévy went on to note in his diary that “his eyes are getting worse”. He also added that by this point, Degas had been forced to start wearing “special glasses which embarrass him very much.”

In 1892, Dr Landolt advised Degas to begin using a stenopeic lens for his left eye and an occluder to cover his right eye so it is likely that these were the glasses Halévy was referring to.

3. How Degas’ Eyesight Affected His Painting

As a result of sightlessness in one eye, Degas’ painting gradually became more and more influenced by his vision.

Throughout his career, he was preoccupied with themes of observation and as Paul Valéry wrote

“What Degas called a ‘way of seeing’ must consequently bear a wide enough interpretation to include way of being, power, knowledge and will…”

Several writers have pointed to the significance of sight and looking in Degas’ work. Charles Stuckey concluded that is it is a “fundamental theme of Degas’s art taken as a whole - an analysis of the act of looking and its consequences”.

Degas is praised for his vision

Indeed, some of the earliest articles written about the artist pointed to the “acuity of his perceptions” and the “authority of his vision”. He was described as a painter who had successfully “renewed the inspiration, the optics and the procedures of his art.”

Julius Meier-Graefe summarised that

“Since Degas came into the world we see it, a large part of it, through his eyes.”

Perception

In his paintings, Degas played with perception. He chose to focus on distant objects in great detail, or to copy the logic of a camera lens, in others works he manipulated the focal plane, blurring some objects and not others. In his own words, Degas’ art exemplified his belief that

“One sees as one wishes to see.”

From Degas’ early notebooks, it is possible to track his interest in cropped or fragmented images which gradually became more pronounced. These are the precursors to the dramatic visual techniques he employed later in his career.

No outdoor painting

Whilst evidence suggests that Degas had never been an avid follower of plein air painting, his eyesight no doubt had a significant effect on the types of subjects he was able to paint. As a young artist he toured Italy and during this time he executed some landscape studies ‘en plein air’.

This is obvious from his notes of the light-effects, the time of day and the weather conditions at the time of painting.

That he was painting en plein air during this period suggests that he had not yet developed photophobia, an intolerance to bright light. However, later he found it uncomfortable to be outside, retreating indoors and towards subjects that allowed him to paint interior scenes.

How Degas adapted ...

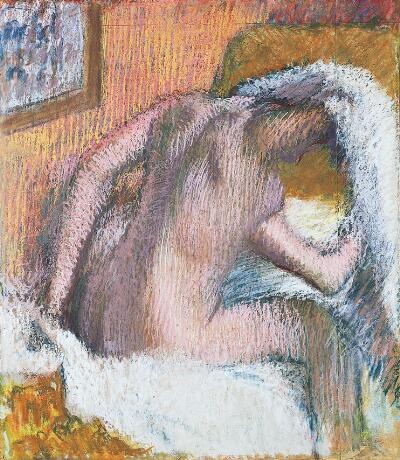

One of the results of Degas’ largely monocular vision was that he also began to paint differently.

To compensate for the effects of his disability, Degas used movements of his head and touch to help him determine space and volume. He also had a system of studying the model from different angles to build up a complete picture, moving himself whilst the model stayed stationary.

Looking in more detail at the effects of eyesight on Degas’ stylistic development, it is possible to see the evolution of his debilitating condition.

Comparing one nude pastel drawing ‘Woman Combing Her Hair’ from 1886 to another ‘Woman Drying Her Hair’ from 1905, one can see the dramatic change. Not only is the form much hazier in the latter painting but the colours are also bolder and less naturalistic.

Asking for help

As his eyesight started to fail, Degas would probably have ceased mixing his own paint and instead have used the paint directly from the tube. Anecdotal evidence also tells that when he was in his 50s, Degas had begun to ask his models to identify the colour of paint that he was using.

Michael Marmor has studied the relationship between eyesight and art, especially in the case of the Impressionists. In an interview for Stanford News, he explained

“There's some reluctance among people in the art world to look outside the historical or psychological influences on the great artists, I'm open to debate about what these visual changes might mean stylistically or aesthetically. What is not open to debate is what the artists saw."

Much like fellow Impressionist artist Monet, Degas’ art was shaped by his own unique way of looking and seeing.