1. The ‘Rouen Cathedral’ artworks

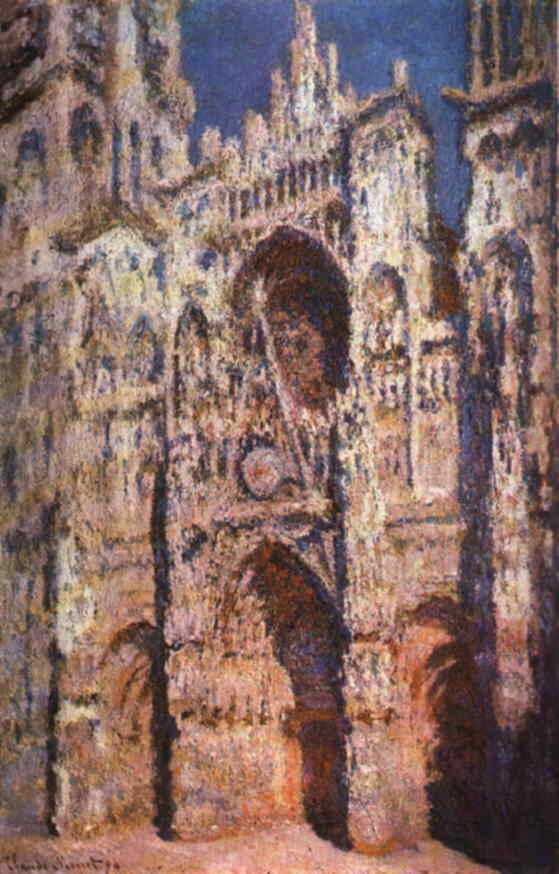

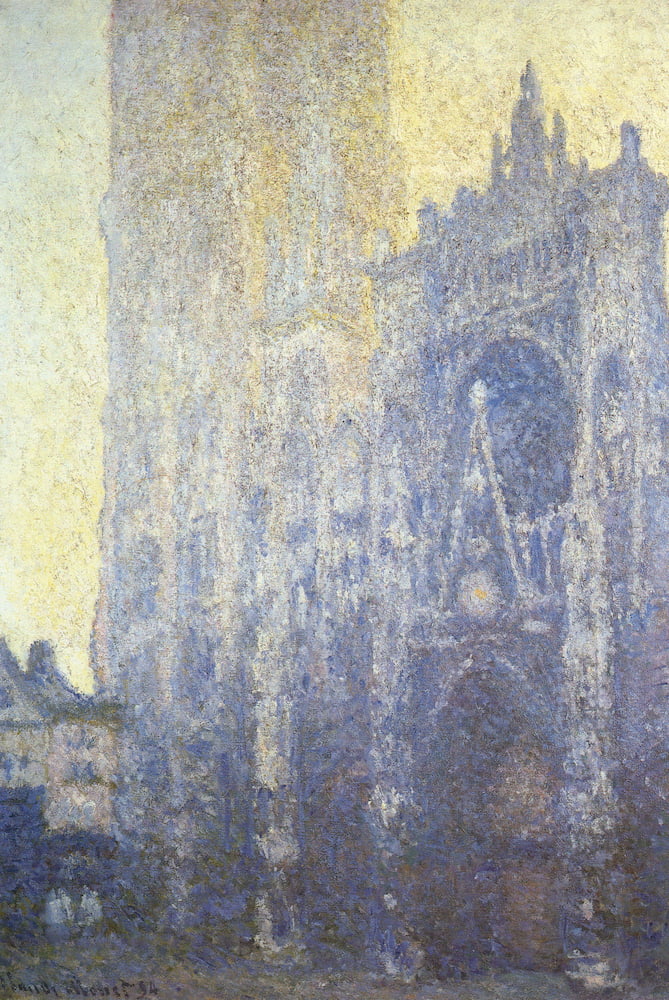

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, the Gate and the Saint-Romain Tower in Full Sun; Blue and Gold Harmony |

|---|---|

| Year | 1893 |

| Dimensions | 107 x 73 cm (42 x 28.7 in) |

| Current location | Musée d’Orsay |

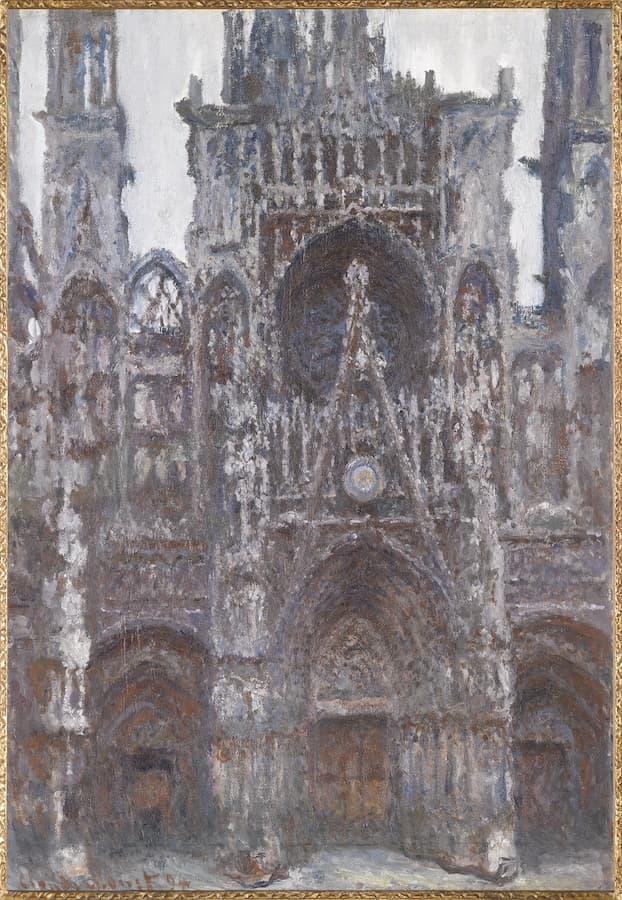

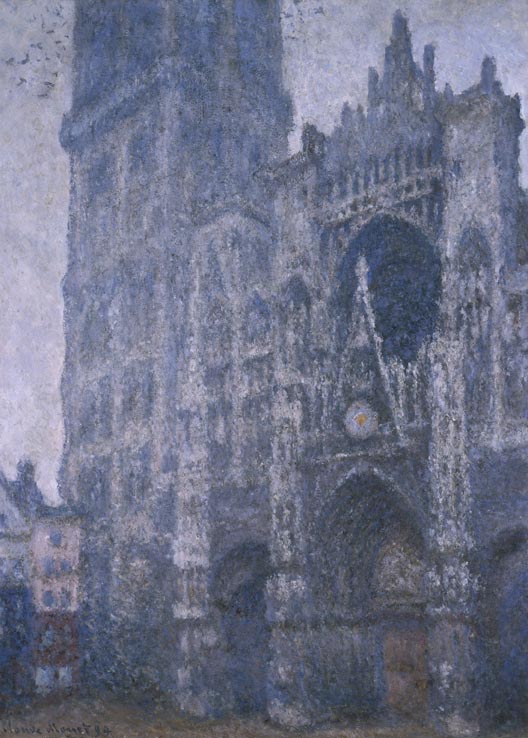

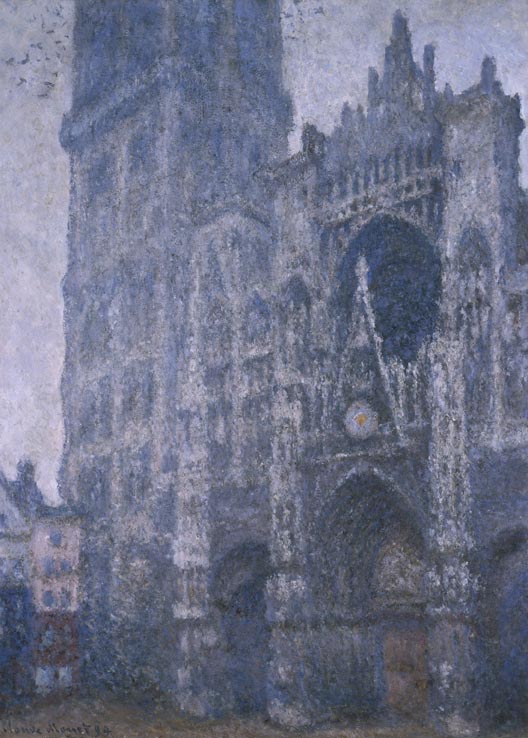

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, the Portal of the Saint-Romain Tower, Morning Effect; White Harmony |

|---|---|

| Year | 1893 |

| Dimensions | 106 x 73 cm (41.7 x 28.7 in) |

| Current location | Musée d’Orsay |

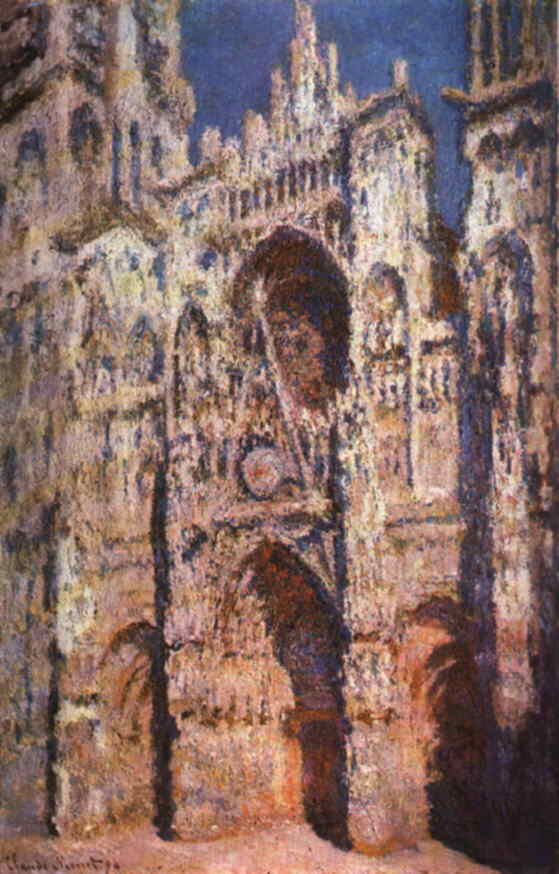

| Title | The Portal and the Tower of Saint-Romain at Rouen Cathedral, Morning Sun; Blue Harmony |

|---|---|

| Year | 1893 |

| Dimensions | 91 x 63 cm (35.8 x 24.8 in) |

| Current location | Musée d’Orsay |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, the West Portal, Dull Weather |

|---|---|

| Year | 1892 |

| Dimensions | 107 x 74 cm (42 x 29.1 in) |

| Current location | Musée d’Orsay |

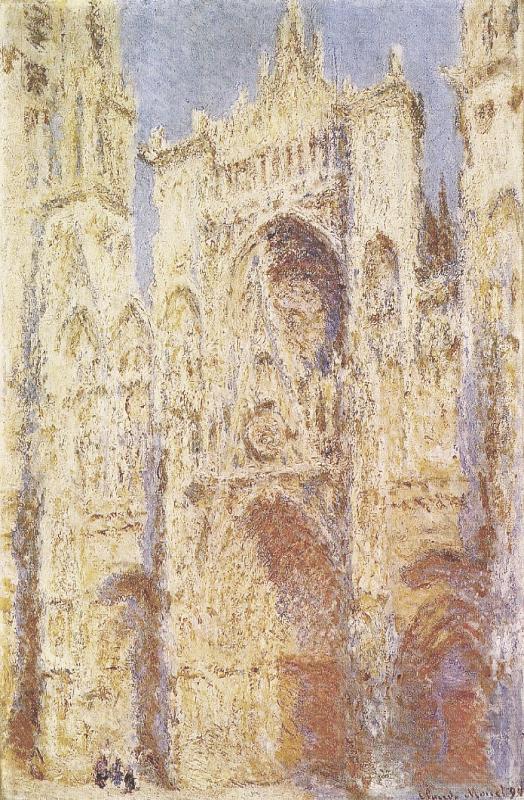

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, Full Sunlight |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 107 x 73.5 cm (42 x 28.9 in) |

| Current location | Musée d’Orsay |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sunlight |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 100.1 x 65.8 cm (39.4 x25.8 in) |

| Current location | National Gallery of Art, United States of America |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sun |

|---|---|

| Year | 1892 |

| Dimensions | 100 x 65 cm (39.3 x 25.5 in) |

| Current location | National Gallery of Art, United States of America |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, West Façade |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 100.1 x 65.9 cm (39.4 x25.9 in) |

| Current location | National Gallery of Art, United States of America |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, the Façade in Sunlight |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 106.3 x 73.7 cm (41.8 x 29 in) |

| Current location | Clark Art Institute |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, Façade One |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 100.4 x 65.4 cm (39.5 x 25.7 in) |

| Current location | Pola Museum of Art |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, Façade, Morning Effect |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 101 x 66 cm (39.7 x 25.9 in) |

| Current location | Folkwang Museum |

| Title | The Portal of Rouen Cathedral in Morning Light |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 100.3 x 65.1 cm (39.4 x 25.6 in) |

| Current location | J Paul Getty Museum |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, Façade, Sunset; Blue and Gold Harmony |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 100 x 65 cm (39.3 x 25.5 in) |

| Current location | Musée Marmottan Monet |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, Red, Sunlight |

|---|---|

| Year | 1892 |

| Dimensions | 100 x 65 cm (39.3 x 25.5 in) |

| Current location | National Museum of Serbia |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, Setting Sun; Grey and Pink Symphony |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 100 x 65 cm (39.3 x 25.5 in) |

| Current location | National Museum of Wales |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, Façade and the D’Albane Tower, Dull Day |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 107 x 74 cm (42.1 x 29.1 in) |

| Current location | Beyeler Museum |

| Title | Rouen Cathedral, Façade and the D’Albane Tower, Grey Weather |

|---|---|

| Year | 1894 |

| Dimensions | 103 x 74 cm (40.1 x 29.1 in) |

| Current location | Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen |

Despite Monet’s misgivings, the ‘Rouen Cathedral’ collection was met with monstrous praise from the public. In addition, Monet’s Impressionist colleagues, Camille Pissarro and Paul Cézanne, were outspoken in their support.

2. What is the current value of Claude Monet’s ‘Rouen Cathedral’ series?

The regard for Monet’s religious series started with their debut. By exhibiting his paintings at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris in 1895, Monet successfully acquired eight buyers within a month.

This was much to gallery-owner Paul Durand-Ruel’s shock, as he had formerly suggested that 15,000 Francs was too steep a price for the works.

However, before the deals were finalised, the French state requested that the whole set be purchased on their behalf. This was a significant offer but Monet declined, preferring to sell his works individually to art dealers, many of whom were his friends and long-term supporters.

In more recent times, the adoration for Monet’s ‘Rouen Cathedral’ series has been rekindled. After the Impressionists suffered almost half a century of being ignored by the art establishment, the 1980s brought about a new wave of passion for figurative art. In 1984, a ‘Rouen’ painting was sold for $2.3 million in New York and things only improved from there.

In 1995, Monet’s ‘La Cathedrale de Rouen, Le Portail, Plein Soleil; Effet d’Apres-Midi’ (1894) was estimated to be worth $11.9 million. The same piece was purchased for £7,591,500 in the same year, further evidence of itspopularity. It now belongs to the Clark Art Institute in Massachusetts in the US.

3. ‘Rouen Cathedral’ 1892 – 1894

Though not Monet’s first or only group of cohesive canvases, ‘Rouen Cathedral’ was certainly the most challenging. Until this point, Monet had painted cityscapes sparingly, preferring to seek his subjects in the natural world.

For the series, he planned his compositions cautiously, choosing to position his easel in five different places. This meant that he could alternate his canvases between painting ‘en plein air’ from a nearby market squareand indoors when the weather conditions worsened.

Monet cast most of his concentration on the edifice’s impressive entryway. Its anatomy was tormenting to the Impressionists: the cavernous archways provided the perfect setup for exploring light and shadow. As predicted, it was this feature that appealed to Monet’s fascination with natural light. While the artist experienced some setbacks, he went about the initial section of his project with an optimistic outlook, writing, “More than ever I detest the things in which I have success at the first attempt”.

However, Monet soon found that the weather conditions, which he was so used to after working in the countryside, had a completely different effect on man-made structures. He penned a letter to his beloved wife, Alice, exclaiming, “I work like a mad man, I cannot stop thinking of anything else but the cathedral”. Placing organic light at the forefront of his technique proved a test for the master painter.

Due to the meticulous planning of his compositions, Monet found the answer to his problem of constantly changing light. The change in seasons convinced Monet to express the fluctuating conditions he found through his palette. Drawing on the physical sensation of temperature, Monet coined colour schemes based on the mood they provided. He named these ‘Harmonies’.

Unlike the Post-Impressionists, the Impressionists were not guided by scientific theories and Monet was no exception. He scorned the colour theories followed religiously by his juniors, instead wishing to rely on his instincts alone when painting. This is likely why Monet’s oeuvre is noted for being incredibly atmospheric and poetic.

Further, Monet’s ‘Harmonies’ depended on the time of year and time of day. In ‘Rouen Cathedral, Façade One’ the frame is dominated by piercing pinks and reds, stippled together to craft the spiked turrets of the cathedral. It is a striking sight, making the facade look ironically devilish. On the contrary, ‘Rouen Cathedral, Façade One’ could not be more different. With spotted brushstrokes of beautiful and pale blues, the church looks like an icy palace.

Although both of these works were completed in 1894, the contrast between them is significant, demonstrating the versatility of Monet as an artist. In 1896, Monet’s confidant, Georges Clemenceau, hinted at the tenacity of Monet’s efforts to depict the cathedral in his essay ‘Pan’. He wrote: “One notices that the art, in its persistence of expressing the nature with increasing exactitude, teaches us to watch, to perceive, to feel.”

4. What was Monet doing when he painted the ‘Rouen Cathedral’ series?

While staying in Normandy, Monet travelled far and wide taking in the landscape.

Though his main base was in Giverny, during the painting of the Rouen Cathedral he took up residence in Rouen, renting a short-term studio. Monet lived parallel to the basilica and he was greeted by the sight of it every morning.

Viewing the monument from his window, Monet worked closely with his subject matter. This proximity was useful for his art. Since light is notoriously tricky to capture on-canvas, Monet formulated a system to help gather the best result.

To execute his works, Monet would sketch the scene on-location, drawing as much information as he could from the scene. Then, whenever the weather turned foul, he returned to the comfort of his studio. In the temporary studio, Monet pieced together his findings and used intuition to fill in the gaps. These reworkings from memory meant that his series took on a slightly fantastical visual, as if part of a fairytale.

5. The Gothic Era

Gothic design is quintessential to France and the cathedral at Rouen is a chief example of this aesthetic. Beginning in the 1300s, the Gothic style dominated European innovation for almost four centuries.

Defined by long windows, decisive arches and looming towers, this trend is immediately recognisable and has made its mark on popular culture.

Although prevalent in the Middle Ages, the Victorian period saw a revival in interest in everything Gothic. Novelists of the 1900s were particularly fond of the movement, moulding gargoyle-infested buildings into eerie backdrops for their gloomy stories. Thus, the ‘Gothic Horror’ genre was born.

Opening with early science-fiction marvels, such as Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’ (1818) Gothic architecture became a setting for the supernatural. In fact, the French author and playwright, Victor Hugo, used a real-life Parisian cathedral as the epicentre of his famous 1831 tale ‘The Hunchback of Notre-Dame’.

When Monet’s ‘Rouen’ series entered the art scene, it was a stroke of luck. Not only was France undergoing a turn-of-the-century push towards Catholicism but Monet was also painting at the same time that gothic horror was becoming immensely popular. Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’ from 1897 paired with Monet’s ‘Rouen’ portraits brought the Gothic Architecture resurrection to its peak.

Perhaps it is ironic that the gargantuan task of painting Rouen Cathedral on repeat caused Monet to have nightmares. Sinking into an episode of despair during his assignment, Monet wrote, “Things don’t advance very steadily … each day I discover something I hadn’t seen the day before … in the end, I am trying to do the impossible.”

Thankfully, Monet found relief after finishing his endeavour. As it stands, Monet’s ‘Rouen’ sequence is integral to nineteenth-century culture, whilst also paying homage to French architectural history. It is no wonder that ‘Rouen’ was so well-liked in its day.

6. Changing perspectives on the ‘Rouen Cathedral’ series

In addition to being popular during the Victorian and Edwardian era, Monet’s ‘Rouen Cathedral’ paintings are still greatly admired.

Twentieth-century creators Wassily Kandinsky and Roy Lichtenstein both openly expressed that they drew inspiration from Monet’s ‘Rouen’ series for their own work.

Today, Monet’s series remains a popular feature in art galleries around the world. The Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, for instance, exhibited 16 paintings in honour of the church through 1994. More recently, in 2018, the National Gallery, London, celebrated the works at their ‘Monet and Architecture’ exhibition, which focused extensively on his urban works.

The absence of civilians within Monet’s Rouen works may be one reason for their enduring popularity, which lets the paintings appear eternal. If someone were to take a snapshot of the cathedral today, they would be met with the same sight that Monet was, albeit perhaps in a less romantic and dreamy light.

Check out the Washington Post's recent Rouen Cathedral interactive guide.