1. Signac’s early years

The son of a middle-class Parisian family, Paul Victor-Jules Signac’s early years were comfortable and creative.

He was born in the autumn of 1863, as modernism was developing, and his family moved to the Montmartre area of Paris when he was still very young. At this time, this region was a hub for art in the city and thus, Signac was exposed to avant-garde culture from an early age.

An artistic environment

His father, Jules Jean-Baptiste Signac, was a luxury saddle and harness maker, as his father had been before, and he owned a shop on the Rue Frochot. Along with his mother, Héloïse Anaïs-Eugénie Deudon, and grandfather, the family lived above the shop.

This dynamic artistic environment undoubtedly had an impact on young Signac, helped by his liberal parents. They encouraged their son to attend numerous exhibitions and immerse himself in the artistic community where they lived, including the work of the Impressionists.

This included attending the Fifth Impressionist Exhibition at the age of 16.

Signac attends Impressionist Exhibition #5

For Signac, this particular event was also his first brush with an Impressionist artist and the experience was not entirely positive.

As he was admiring the works in the show, Paul Gauguin approached him and scolded him sharply for sketching a work by Edgar Degas, which Gauguin interpreted as ‘copying’.

He was promptly thrown out of the gallery for disregarding the unwritten rules of the exhibition! Despite Gauguin’s ill-humoured introduction to the artists of the Impressionist movement, Signac went away with a feeling of fascination with this new style of painting.

Signac's father dies

Sadly, shortly afterwards in 1880 Signac’s father died of tuberculosis. The family were close and Signac and his mother, Héloise, found the death very difficult.

Héloise made the decision to leave the shop and apartment and move, along with Signac’s grandfather, to the new suburb of Asnières. After having sold the family business, they were able to buy a nice house and live well. However, Signac did not like his new home and began dividing his time between Montmarte and Asnières, renting a room of his own.

Young man about town

Quickly becoming a young man and with a new found freedom, Signac began spending more time exploring the nightlife of Paris. Here he began socialising with artists, writers and musicians. His location at the centre of a thriving creative neighbourhood at a young age made him hungry for debate, politics and intellectual discussion.

Most notably, he frequented Le Chat Noir in Montmartre, a favourite cabaret among the artistic community of Paris. The characters he met in these bars, cafes and clubs would go on to be strong supporters of his work in the future. It was also around this time the Signac produced his first paintings, in the winter of 1881 and 1882.

Self-taught

Interestingly, Signac was almost entirely self-taught. He received a few painting lessons for free from Émile Bin, a portraitist and history painter, but otherwise he learnt how to paint by studying the paintings of some of the leading Impressionist artists.

This influence is evident from his depictions of the town of Port-en-Bessin from 1883, which clearly echoes Claude Monet’s distinctive style.

During a summer spent in the coastal town, Signac painted a number of studies that demonstrate his keenness to master the Impressionist technique. The works are painted with forceful, long brushstrokes and bright colours, which give his studies a feeling of energy and vitality.

2. Signac and the Impressionists

Unlike earlier Impressionist artists, Signac grew up in a Paris that was already embracing non-academic, avant-garde art styles.

As Signac was developing in his career as an artist, one of the most talked about movements in French art was Impressionism. Artists like Claude Monet and Édouard Manet were by then becoming more popular and widely known, but their work was also still cutting edge.

The attraction of impressionism

It is unsurprising, then, that he was drawn to the Impressionists as a young student and their innovative techniques had a significant effect on Signac’s own style.

In particular, one can see the influence of the Impressionists in Signac’s coloristic approach to painting, as well as his mastery of portraying movement. He embraced the en plein air method of painting popularised by the Impressionists, focussing in particular on landscape paintings and especially coastal scenes.

Sailing

As an ardent sailor - he named his first boat ‘Manet Zola Wagner’ and his second ‘Olympia’ after a painting by Manet - the sea is interwoven into his art. This ensures that much of his work has a sense of fluidity and energy, befitting of his watery subjects.

Monet's Influence

The most significant Impressionist artist for Signac was undoubtedly Monet, though Gustave Caillebotte was also an important source of inspiration.

Indeed, Signac credited Monet’s 1880 exhibition at the offices of the journal ‘La Vie moderne’ as being one of the principal motivations for him beginning a career in art. This was a pivotal moment for young Signac as he admired Monet’s methods of capturing the effects of natural light, with no subject too ordinary to grace his works.

Politics

In addition to the evidence of Impressionism in his artworks, Signac also shared his political views with certain prominent Impressionists. He publicly endorsed anarchism in 1888 and he contributed to the pro-anarchist and communist newspaper ‘Les Temps Nouveaux’ or ‘The New Times’.

In doing so, he aligned himself with painters such as Camille Pissarro, who was also a strong supporter of anarchism. During the Dreyfus Affair, Signac signed a collective statement publicly supporting Zola, who was incidentally one of his literary idols.

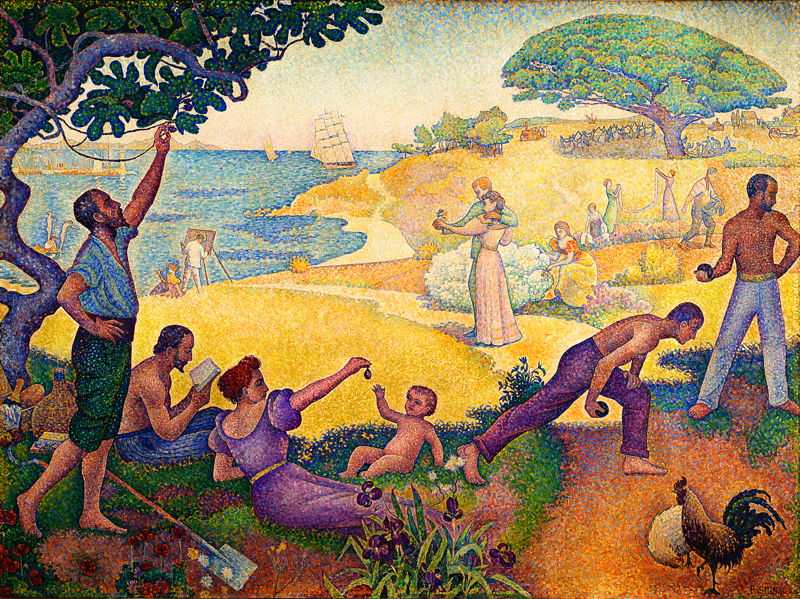

In the Time of Anarchy/Harmony

Signac’s anarchism went one step further in 1893 when he named one of his paintings ‘In the Time of Anarchy’. It was a strong statement. He later changed the title to ‘In the Time of Harmony’, however, when the government began to persecute known anarchists.

This painting was completed after Signac had moved to St-Tropez in 1892. It is enormous in scale and can be seen to represent Signac’s commitment to politically critical, avant-garde art centred on anarchist ideals.

The setting, on the southern coast of France, offers an interesting contrast to the earlier associations of this landscape with classical art. Through this painting, Signac reclaims the setting for his own, establishing a new cultural geography that is based on a left-wing vision of the Mediterranean coast. ‘In the Time of Harmony’ was one of a series of politicised pastoral paintings produced by Signac in the 1890s.

Personal Life

In his personal life, Signac also became closer to Pissarro when he married his cousin, Berthe Roblès, in 1892.

The pair met in Le Chat Noir and she is painted into one of Signac’s earliest paintings, ‘The Red Stocking’ from 1883. She was a milliner by trade and she also features in one of his most famous works - ‘The Milliners’ from 1885-86.

There is evidence that the two became lovers shortly after meeting and began living together.

3. Signac and Neo-Impressionism

Early into his painting career, in 1884, Signac helped to found the Salon des Indépendants, an exhibition created for artists who were disillusioned with the Paris Salon and the official art establishment.

It was through the Salon des Indépendants that Signac first met Seurat and the two emerging artists quickly became friends.

The first meeting

This crucial meeting would lead to the pair breaking away from the Impressionist movement to develop their own style. Seurat was the first to do so with his work ‘Bathers at Asnieres’ from 1884, which granted him immediate fame.

Signac was slower to adopt the Neo-Impressionist technique, continuing to develop his style under the encouragement of Pissarro and Armand Guillaumin, another Impressionist artist. However, during frequent meetings between Seurat and Signac, in which they discussed colour theory and the work of Michel-Eugène Chevreul, both artists began to refine and develop their unique style.

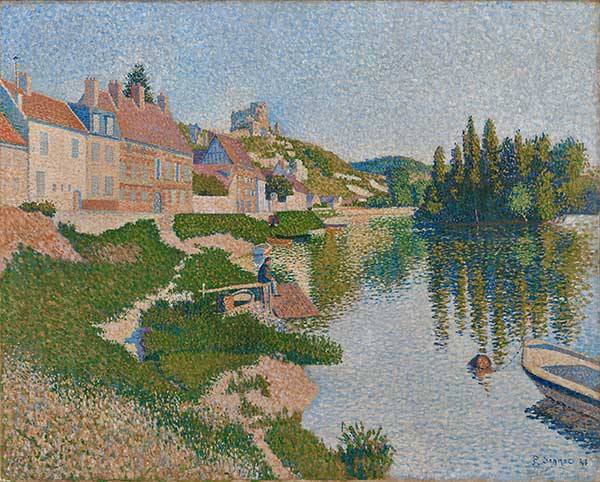

Les Andelys, The Riverbank

This crossover period is displayed in Signac’s 1886 work ‘Les Andelys, the Riverbank’. This painting has the air of a Pissarro, featuring the short, rapid brushstrokes characteristic of the Impressionist style. The attention to natural light and the bright, gentle palette is also typical of Impressionism.

It was during this summer, in 1886, that Signac worked on developing his Neo-Impressionist approach. Whilst living in Les Andelys, he painted ten landscapes in close collaboration with Seurat. The technique the two friends developed was Divisionism, better known as Pointillism.

Pointillism

Pointillism involved applying paint to the canvas as small daubs or spots of colour in a precise manner, using the theory of optical mixing to create a cohesive whole that appears as solid, intense colour when viewed by the human eye.

Despite the clear division between Impressionism and this Neo-Impressionist technique, both Signac and Seurat exhibited at the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition and the Salon des Indépendants, alongside Impressionist artworks. Their works were largely met with positive criticism, aside from protests by Edgar Degas and Eugene Manet, Édouard's brother.

A symbiotic relationship

By this time, the artists had a strong bond of professional and personal friendship. They complemented one another - Seurat as the introverted visionary and Signac as the outgoing, enthusiastic publicist for their new school. Seurat helped Signac refine his style whilst Signac introduced Seurat to his extensive social network, which included some of the leading artists and writers of the avant-garde.

During this time, Signac painted tightly ordered and regimented works, typical of the new Pointillist style. This includes paintings like Gasometers at Clichy, from 1886, based closely on Seurat’s technique. Signac’s particular focus on industrial subjects has been linked to his anarchist politics and he manages to render rather ugly architecture with a positivity and luminosity, imbibing his settings with a certain romanticism.

Both artists sought to depict working-class life as opposed to more popular, bourgeois themes often depicted by Impressionist artists. As he became more confident in the technique, Seurat also began to infuse his artworks with even more intense, energised colour, echoing the animated palette of his earliest paintings.

Seurat's death

In 1891, Seurat died suddenly, leaving Signac as the sole vanguard for the Neo-Impressionist movement.

This was a crucial moment in Signac’s career and, equally, in the development of Neo-Impressionism. Despite Seurat’s passing, Signac steadfastly continued to champion the movement he first started, including penning a manifesto in 1899 titled ‘From Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism’, which was his first major written work.

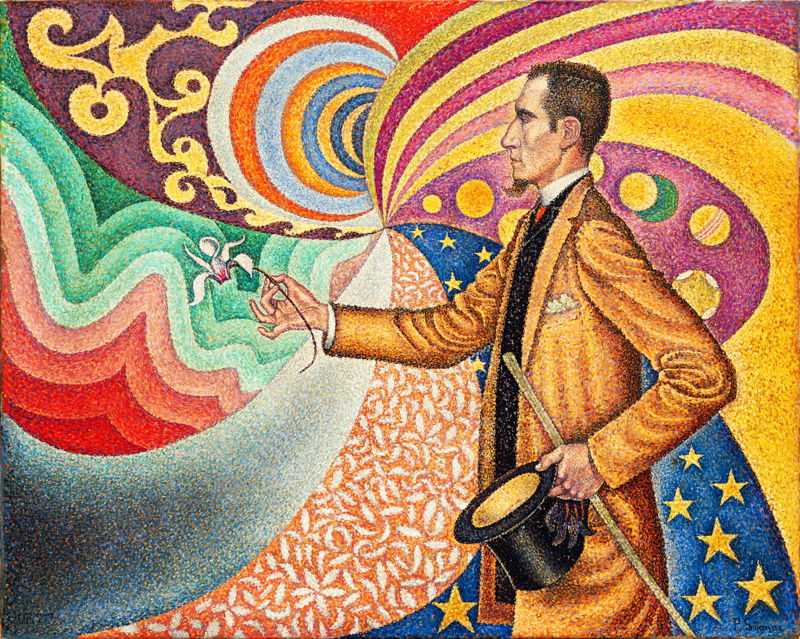

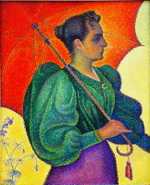

Portraits?

Roblès appears again in Signac’s painting ‘Femme à l’ombrelle’ or ‘Woman with a Parasol’ from 1893. This is one of the few portraits Signac painted in the Neo-Impressionist style. In this work, he adopts the theories of simultaneous contrast and optical mixing that were central to the Pointillist technique. The composition is deliberately two-dimensional, producing a decorative look that is heightened by the extravagant fashion and stately pose of the figure.

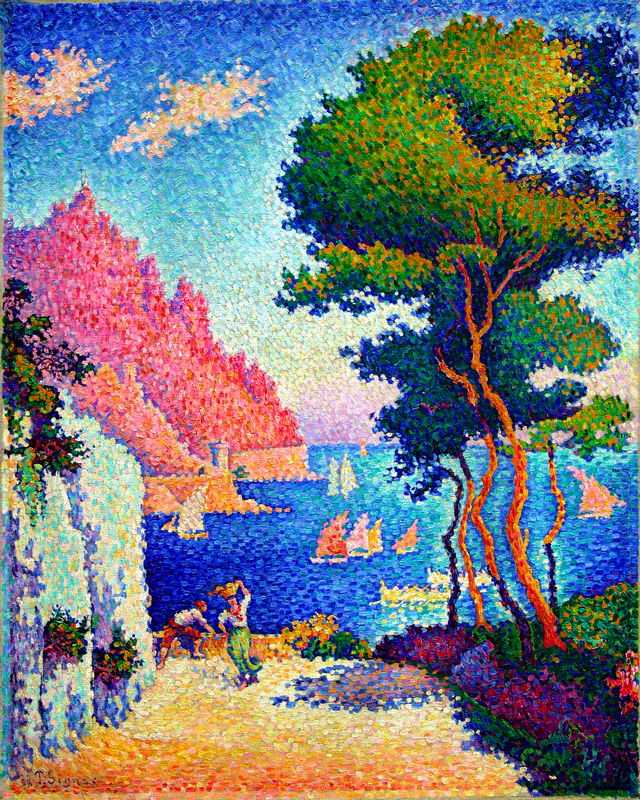

At the same time, Signac began to be more experimental in his interpretation of the Neo-Impressionist technique, introducing a wider array of colours into his works. His brushstrokes gradually became looser and less retrained and his works overall developed a more expressive style.

Experimentation

This effect be seen in paintings like ‘The Pink Cloud, Antibes’ from 1916, which is a vibrant and exuberant work, demonstrating his freer approach to painting. By this time, Signac had separated from his wife and was living with his lover, Jeanne Selmersheim-Desgrange, and their young daughter Ginette in Antibes.

Waterscapes

On the coast, Signac almost exclusively painted scenes of the water, including the harbour, riverbanks and cliffs. The bright pigments that he continued to daub on the canvas, just in a livelier manner than before, combine to create the impression of constant movement. The effect is more romantic than his works from the 1880s and 1890s and demonstrates the culmination of Signac’s own, original style.

Similarly, Signac’s interest in the musicality of colour and art shines through in these later works. He began giving his paintings musical subtitles, such as ‘Evening Calm, Concarneau, Opus 220 (Allegro Maestoso)’ from 1891.

This work, depicting fishing boats near the French town of Concarneau, is part of a series focussing on harmony. Signac is quoted as saying that color has “in some ways elements of mathematics and music”.

4. Signac’s legacy

The energetic Signac eventually died in 1935 from septicemia.

During World War I, his artistic output decreased significantly and the Salon des Indépendants were temporarily suspended.

Disillusionment

Signac became disillusioned and disconsolate during the war years, painting just seven works in three years.

It was only in 1919 that he began to paint more frequently once more. This was not out of any particular artistic drive, however, but financial need. He was forced to paint in order to be able to support himself and his family.

After signing an annual contract with three art dealers, Signac’s output went up to 21 paintings per year. Despite fulfilling his obligation and succeeding in keeping his family afloat, for much of his later life Signac was more preoccupied with politics than with painting. At the same time, his health began to fail.

Politics and writing

The legacy Signac left behind was significant. In his life, he played an important part in the establishment of the Salon des Indépendants, which gave artists an alternative exhibition space to forge new styles that was separate from the tight restrictions of the Salon.

As well as his paintings, he also generated an enormous body of writing, both fiction and non-fiction. Furthermore, Signac was an ardent supporter of anarchism, whilst being an outspoken anti-fascist.

Signac's work

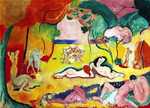

Signac’s oeuvre is regarded as a pillar of modern art and his advocacy of the theories of colour formed an important base for 20th century greats like Henri Matisse and the Fauvists.

Matisse spent time at Signac’s home in St Tropez and the influence of the Pointillist technique on his work from this period is evident.

Cubism also drew on Signac’s flattened and at times fragmented style, albeit less strongly than Fauvism.

Earlier in his career, after an initial introduction in 1886, Signac also helped Van Gogh to learn how to paint in the Neo-Impressionist style, heavily influencing his unique form of Post-Impressionism that is still considered revolutionary today.

Though Signac has often been regarded as living in the shadow of his colleague Georges Seurat, his exuberant character enabled his influence to spread through the French avant-garde.

The autodidactic artist opened up a new wave of highly expressive, colour-centred art utilising bright and harmonious colours. In doing so, he was able to create a visual vocabulary that was more about enjoyment than rigorous academic practice and this was a crucial beginning for the avant-garde art to come.