1. The Background to Exhibition #4

Towards the end of the 1870s, many of the Impressionists were becoming despondent.

They had achieved no more successes since their previous exhibition in 1877 and a number of artists in the group began to drift away.

There were some strong supporters in favour of staging a Fourth Impressionist Exhibition, namely Caillebotte, Degas and Pissarro. They felt that the only way forward for the Impressionists was independent exhibitions of their work. Indeed, following the previous Impressionist Exhibition, the group had begun to have pieces written about them by the press and they saw this as a positive development for the group.

Claude Monet

In contrast, Monet was extremely unwilling to exhibit with the group again. He felt that the reputation of the Impressionists was having a negative effect on sales of his work and as he was in dire financial need at this stage, he was becoming increasingly desperate.

Édouard Manet, Georges De Bellio and Caillebotte all lent him money to pay for an apartment and the moving of his things but he continued to rack up debts which he was unable to pay.

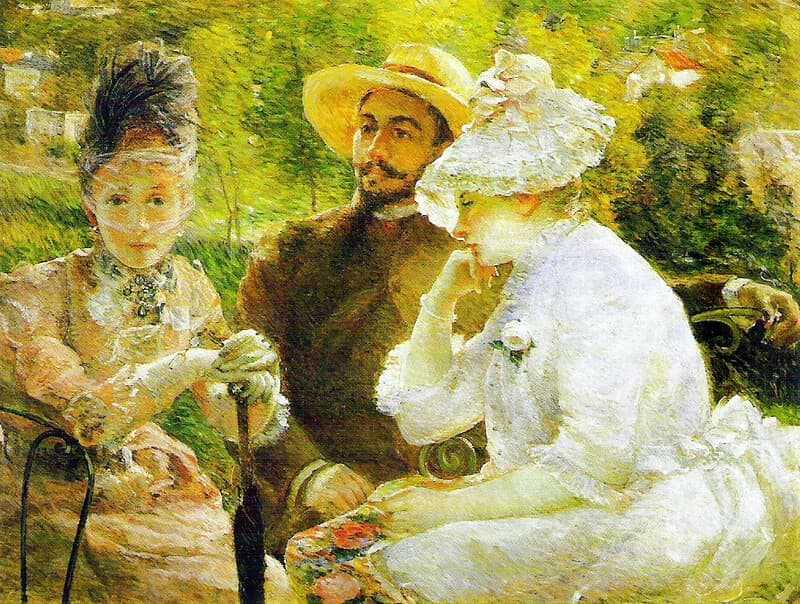

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

In the end, it was Renoir who was the first to leave the Impressionists.

He wanted to submit his portrait of ‘Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children’ (1878) to the Salon and made the difficult decision to privilege the official exhibition over the Impressionists. Breaking with Degas’ strict ruling that no Impressionist artist should exhibit at the Salon, he was forced to separate himself from the group.

His conviction paid off, however, and his painting was exhibited at the Salon in 1879. Marguerite Charpentier used her influence to ensure that the painting had a prime position in the exhibition’s centre hall. The work was greatly admired by a number of affluent collectors, despite the informal poses of the sitters.

Most notably, the painting caught the attention of Paul Bérard, a wealthy and well-known French collector. He invited Renoir to his country chateau in Wargemont to paint his family. During the summer, Renoir found a haven of picturesque scenery, friendly acquaintances and plenty of smiling, sun kissed subjects to fill his canvasses.

Alfred Sisley

Caught in the same dilemma, Alfred Sisley also began to retreat from the group.

He had begun painting landscapes around Marly but was in dire financial difficulty. Several times he was forced to move to smaller lodgings in ever cheaper locations in order to continue to afford his rent payments. In this perpetual state of instability, he quickly became depressed.

Sisley’s reasons for leaving the group are best summarised in a letter he wrote to Théodore Duret, stating,

“I can’t go on treading water like this. […] It is true that our exhibitions have made us better known, and that has been useful, but I don’t think we should isolate ourselves like this any longer. I have decided to submit some works to the Salon. It they are accepted, and I may be lucky this year, then I think I could make some money. With that in mind, I’m hoping the friends who really care about me will understand my decision.”

Unfortunately, his work was rejected by the Salon once again and on hearing the news he became even more despaired.

Paul Cezanne

Meanwhile, disillusioned with the state of the Impressionist movement, Paul Cézanne left Paris. He was horrified by Monet and Renoir’s disloyalty to the group and he shut himself away, withdrawing once more to Provence.

Despite his geographical distance, Cézanne did maintain close ties with Pissarro, his original teacher and mentor, but he did not exhibit with the group again.

2. Organising the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition

The Fourth Impressionist Exhibition took place at 28, avenue de l’Opera, a venue secured and paid for by Caillebotte.

In total, 15 artists contributed to the exhibition. As well as the core group - Caillebotte, Pissarro and Degas - there were also a range of new artists added to the show.

New Artists

Among them were Félix and Marie Bracquemond, Ludovic Piette-Montfoucault, and Adolphe-Félix Cals. There were also a number of Degas’ friends and associates, including Henri Rouart, Jean-Louis Forain, and Federico Zandomeneghi, an Italian Impressionist painter.

The Title

The exhibition’s full title was ‘4ème Exposition faite par un groupe d’artistes Indépendants, réalistes et Impressionistes’.

This somewhat complicated name was decided upon as a form of compromise between Caillebotte and Degas, to avoid the exhibition being too heavily associated with Impressionism. Despite the change of name, the group continued to be referred to as the Impressionists by the press and among the artists.

Thanks to Degas’ uncompromising ruling on the Salon, many core Impressionist artists had been forced out of the group. He remained steadfastly committed to his principles and was disgusted with the artists who showed disloyalty to the group. Caillebotte was far more tolerant of their decision, which angered Degas even further.

The Difficult Degas

Degas showed just how obstinate he was when he fell out with Pissarro for congratulating Renoir on his success at the Salon.

Once again, it was Caillebotte who worked to soothe the tensions in the group, writing to Pissarro that,

“you are less complicated, and fairer, than Degas […] You know there is only one reason for doing any of this, the need to make a living.”

Eventually, Degas forgave Pissarro and the bond between them was repaired.

In this climate of tension and desertion, Caillebotte and Degas tentatively approached Berthe Morisot to see what her position on the matter was. Morisot had recently given birth to a daughter, Julie, who occupied much of her time.

Morisot

Morisot revealed that she had no desire to exhibit with the Salon and she was not in need of money. As a result, her loyalties naturally lay with the remaining Impressionists in the group.

However, she had very little to offer up for the exhibition as her painting output had dropped. She had painted very little since the birth of Julie, with the exception of some decorative fan still life works.

Exactly what Morisot contributed to the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition is unclear, as her work was once again not included in the exhibition catalogue.

A letter from Monet after the event shows that she clearly did exhibit something. It is likely, therefore, that she would have contributed a number of the fan paintings. Degas, Pissarro and Marie Bracquemond all had their own versions, which were hung together in one room, so most probably Morisot’s work joined them.

Paul Gaugin

Another artist missing from the exhibition catalogue was Paul Gauguin, who arrived at the very last minute with a statuette to contribute to the show.

Just 10 days before the opening of the exhibition, the group agreed to invite Gauguin to exhibit, he was still largely unknown at this point. In a letter to his unofficial teacher, Pissarro, Gauguin wrote:

“I accept with pleasure the invitation which you and M. Degas were kind enough to send me”.

A Yes from Monet

Despite Degas’ distrust and his own vows to the contrary, Monet eventually exhibited with the Impressionists once again.

This was due in no small part to the efforts of Caillebotte who wrote frequent and encouraging letters to Monet to convince him to join them. He also borrowed paintings from collectors of Monet’s work, even taking care of the framing himself. In the end, Monet contributed 29 paintings in total.

In contrast, Degas listed 25 works in the catalogue but Caillebotte revealed in a letter to his friend what he called the “ridiculous circumstances” surrounding Degas’ contributions. On the first day of the exhibition,

“there were eight canvasses by him. He is very trying, but we have to admit that he has great talent.”

It is therefore not clear how many canvasses Degas actually exhibited. It seems to have been less than ten - presumably because Degas was a perfectionist who did not think the other 15 works were worthy of public review.

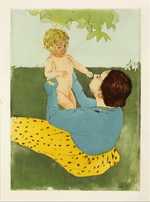

3. The Role of Mary Cassatt

Crucially, the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition saw the arrival of Mary Cassatt.

Cassatt, an American painter, was keen to exhibit with the group after becoming acquainted with Degas. She wanted to lend her support to the struggling group and even turned down other exhibitions in order to privilege the Impressionists.

In a letter to the Society of American Artists in New York, she wrote:

“There are so few of us that we are each required to contribute all we have. You know how hard it is to inaugurate anything like independent action among French artists, and we are carrying on a despairing fight and need all our forces”.

Cassatt was passionate about the cause and in her writing, it is evident that she felt her contribution was vital to keep the Impressionist movement alive.

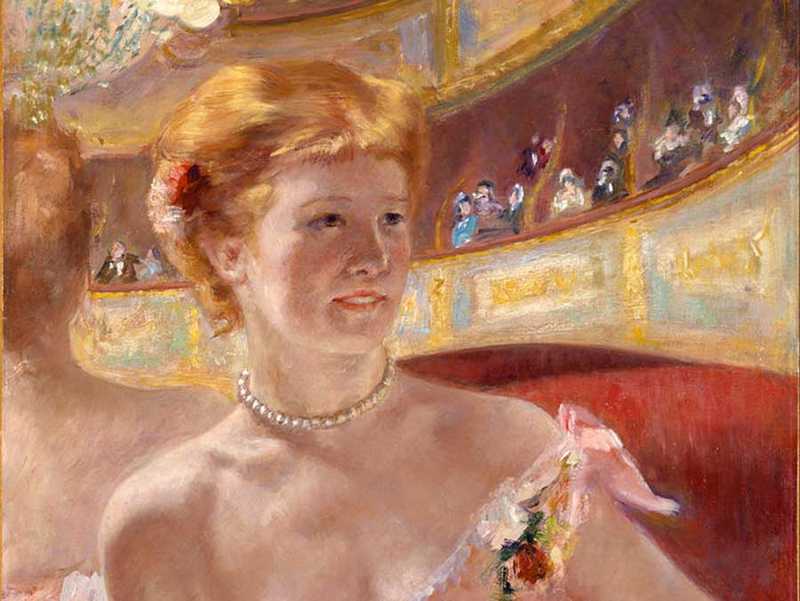

Mixed Media

The Fourth Impressionist Exhibition was a watershed moment for both Degas and Cassatt, with both artists taking the decision to exhibit mixed media works as well as a number of striking canvasses.

Taking a daring and fashionable approach to framing, Cassatt exhibited her works in bold red and green frames. This included ‘Woman with a fan’ from 1878-79 and ‘Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge’ from 1879.

The latter painting received much acclaim thanks to its soft tones and the captivating effect of the artificial light on the sitter’s skin.

4. The Critics Respond

Despite the intense difficulties the group had faced in the lead up to the exhibition, the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition was a resounding success.

Over the course of a month, the show attracted more than 16,000 visitors.

A successful exhibition ... at last

Rather than the scornful response the Impressionist Exhibitions had received in previous years, the crowd seemed to be more respectful and more admiring in 1879. Caillebotte reported to Monet, that the visitors were

“always in a gay mood. People have a good time with us”.

Thanks to the high number of visitors, the expenses for the exhibition were met and exceeded. There remained over 6,000 francs in profit. Each artist received 439 francs from the exhibition and some artists were able to sell their artworks too.

A few unnoticed visitors to the bustling exhibition included Georges Seurat, who was just 19 at the time, and some of his friends. He was so astounded by the exhibition that he resolved to quit the Ecole des Beaux-Arts immediately and take a studio to begin studying on his own.

The response of the critics

The critical response to the exhibition provided the greatest evidence that things were starting to change for the group. Though there was a large number of the usual critiques and caricatures, overall the press was far fairer and even complimentary in their reviews of the exhibition.

Works that especially caught the attention of the critics included Degas’ painting ‘Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando’ from 1879.

Émile Zola wrote that Degas possessed, “astonishing truthfulness” and Joris-Karl Husymans in L’Art Moderne praised the artist’s technical abilities.

Unlike in previous years, Zola devoted very little time to reviewing the exhibition as a whole. In a Russian language publication, he wrote that the Impressionists study,

“the changing aspects of nature according to the countless conditions of hour and weather […] They pursue the analysis of nature all the way to the decomposition of light, to the study of moving air, of colour nuances, of incidental transitions of light and shadow, of all the optical phenomena which make an horizon […] so difficult to represent.”

Zola causes ripples

Zola also discussed the work of Édouard Manet and Monet but incidentally there was some controversy surrounding the translation of his writing into French. ‘Le Figaro’ printed an article titled ‘M. Zola has broken with Manet’, quoting Zola’s review of Monet’s work. He was less than complimentary stating that, “For a moment Manet [Monet] inspired great hopes, but he appears exhausted by hasty production; he is satisfied with approximations”.

This tendentious review of Manet’s art forced Zola to write to him personally, assuring Manet that “the translation of the quotation is not exact” and that he had written “with solid sympathy for your talent and your person.” In fact, Zola had written about Monet, but he did not mention this in his letter to Manet, which was subsequently reprinted in ‘Le Figaro’ at Manet’s insistence.

Duranty

One of the most surprising reviews of the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition, however, was from Louis Duranty, who had previously been somewhat reserved in his praise. He especially commended the work of Cassatt, as well as complimenting the work of Monet and Pissarro, and Degas’ circle of artists.

La Vie Moderne

In May, Marguerite Charpentier encouraged her husband to launch a new magazine centred around the group, which became known as ‘La Vie Moderne’. This fashionable publication covered all aspects of artistic, literary and social life. They also established the publishing headquarters in a studio with an adjoining art gallery that could be accessed from the street.

The Charpentiers’ aim was to recreate the effect of the artist’s studio in the gallery, to allow collectors to drop by and view the works, without having to make a trip to a private studio. For Paris, this was an entirely new and modern way of exhibiting art that had never been seen before.

5. The Aftermath

The success of the exhibition strengthened the bond between the remaining Impressionists in the group.

Degas, Cassatt, Caillebotte and Pissarro had been forced to work closely in order to bring the exhibition to pass and their friendship had become solidified as a result.

The Printing Press

During this time, they had also discovered a shared interest in print making, aided by Cassatt who had studied print making in Rome. Degas owned a printing press and the group began working together, experimenting with different techniques and developing their individual styles, whilst sharing tips among them.

This collaborative effort led to the invention of the ‘manière grise’, a method for achieving lightly shaded tints or tonal areas in prints. They also innovated a new method for creating grainier textures in the prints, using a copper plate with a pencil-shaped emery stone. These were extremely exciting discoveries for the group and for the medium.

For Cassatt, the colour printing she did during this period represented an important turning point in her career, allowing her to experiment with flowing, striking designs that distinguished her work from her contemporaries. Thanks to their successes, the group decided to launch an illustrated journal of prints titled ‘Le Jour et la nuit’ or ‘The Day and The Night’. The plans were largely pushed forward by Degas, aided by Cassatt and the two became even closer friends during the process.

Remaining tensions

Though the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition did not solve the Impressionists’ woes overnight, it did demonstrate the value of commitment to the cause. The artists who showed their work in the exhibition were rewarded with large numbers of visitors and some positive reviews. Nonetheless, the divide between the Salon artists and the independent Impressionist exhibitors had never been more apparent.