1. The Dreyfus affair through the eyes of Julie Manet

Born in 1878, Julie Manet was the daughter of Berthe Morisot and Eugène Manet.

From an early age, Julie was conducted into the affluent circles of French artistic and literary society and she became well acquainted with many key Impressionist artists.

She sat as a model for her uncle, Édouard Manet, Auguste Renoir and Morisot, and possibly for Edgar Degas as well.

Sadly, Julie was orphaned at the age of 16 when Morisot and Eugène Manet both died within just three years of each other. (Stéphane Mallarmé became her guardian and she went to live with her cousins, who were close family and close friends.)

Before her parents’ deaths, Julie had decided to start a diary, filling it with thoughts and experiences she had as a young teenager. It was not a

“neat ladylike leather bound volume, but untidy notes scribbled down in old exercise books, often in pencil, the presentation as spontaneous as the contents”.

As well as documenting the pain of losing both her parents, Julie’s diary also covers the drama of the Dreyfus affair. From her writing, we can build up a colourful and candid image of the Impressionists at this time and their views on the Dreyfus affair.

Her diary has been translated into English and remains in print.

2. The Dreyfus affair and the Impressionists

The Dreyfus affair was fervently debated throughout France and the strong emotions and anger of the country was echoed in Impressionist circles.

Unlike in previous political debates, the artists were not unanimous in their opinions of Dreyfus and this led to a crucial and damaging divide in the group.

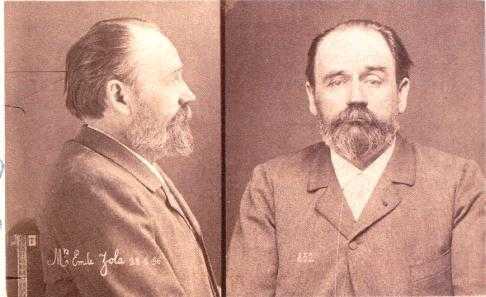

Emile Zola

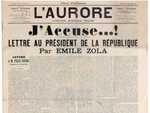

To add to the war of words, Emile Zola stepped forward to defend Dreyfus. He penned a series of articles in Le Figaro towards the end of 1897 in which he raised the question of Dreyfus’ innocence. This series came to a head when he wrote an open letter in January 1898, which was published on the front page of L’Aurore.

This pro-Dreyfus paper, edited by Georges Clemenceau who was also a friend of many Impressionist artists, gave Zola the space to write a vehement declaration that began with the words “J’accuse” (meaning "I accuse").

Zola attacked the French army, accusing them of fabricating evidence and withholding information, and he demanded that the government reopen the case.

For his courage, Zola received death threats from anti-Dreyfus, pro-military campaigners. Shortly after the letter was published, Zola was convicted of libel - writing false statement or defamation, deliberately damaging to a person or people’s reputation - and he was sentenced to imprisonment. Before the sentencing, he fled to England and stayed there for a year in 1898, before eventually venturing back to France.

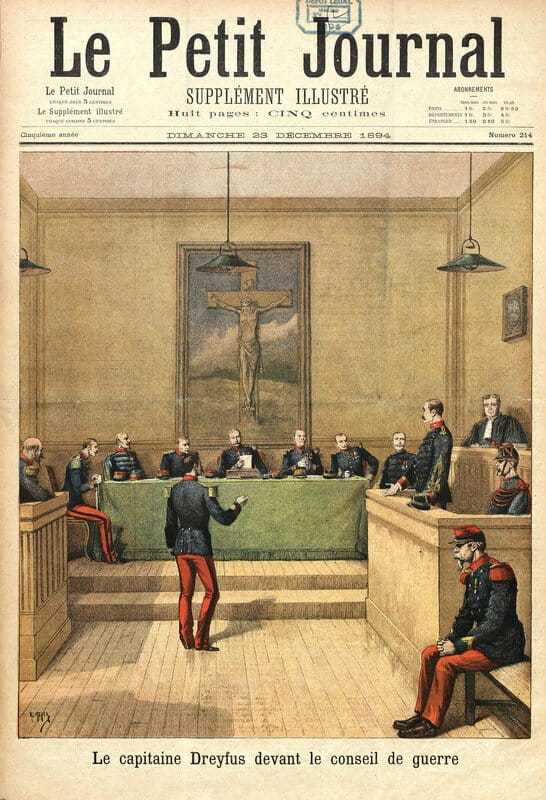

Dreyfus' retrial

Zola’s actions put new pressure on the French government to have a retrial for Dreyfus. He was found guilty once again but this time he was pardoned and set free. It was not until 1906 that he was completely acquitted of the crime he did not commit.

As Zola had been a long-term friend of the Impressionists, particularly Paul Cézanne, and had supported and critiqued the movement throughout its development, his involvement in the Dreyfus affair caused ripples through the Impressionist group.

The sentiments included in his letter were felt especially keenly in the Impressionist circle, with some artists supporting his actions and others condemning him.

Overall, the Dreyfus affair exposed just how different the political worlds that the artists inhabited were. It laid bare the extremely divergent opinions of the members of the group, disrupting their social circles, their shared exhibitions and even their artworks.

The once united group was split apart.

3. Which impressionists were pro-Dreyfus?

One of the first Impressionist artists to come out in support of Zola was Claude Monet.

Monet quickly came to Zola’s defence, publicly agreeing with his pro-Dreyfus stance and showing his deep respect for the man he had known for almost 40 years.

Letter of congratulations

Monet’s position is evident from letters of congratulations written to Zola in December 1897 and January 1898.

He had hoped to travel to Paris for Zola’s trial but was unable to do so because of illness among his close family members. Instead, he stayed informed of news in Paris through his close friends and fellow Dreyfusards, Octave Mirbeau and Gustave Geffroy.

Cassatt, Signac and Pissarro

Other Dreyfusards included Mary Cassatt, Paul Signac and Camille Pissarro.

Pissarro had long held liberal, even anarchist views, but he was also personally affected by the savage anti-semitism that had found an outlet through the Dreyfus affair. As a Jew, he became the victim of anti-semitic attacks, including from other artists in the Impressionist group.

Pissarro first came around to the Dreyfusard cause through his anarchist connections. In 1896, Bernard Lazare forwarded Pissarro a copy of his book titled ‘L’Antisémitisme’. This work, first published in 1894, was a careful and eloquent analysis of anti-semitic prejudice, written by Lazare himself, who was also an anarchist and a Jew.

Pissarro wrote to Lazare after reading the work:

“[How] happy I am to see a Semite defend my ideas with such eloquence; so there is at least one Jew, anarchist and well-informed, who is capable of raising his voice with authority.”

The following year, Pissarro received a second work by Lazare titled ‘Une erreur judiciaire. La vérité sur l'affaire Dreyfus’ (A Miscarriage of Justice: the truth about the Dreyfus Affair) and this was the first signal for Pissarro to begin to doubt Dreyfus’ guilt.

Zola’s letter in L’Aurore brought him to his final conclusion and he wrote a letter of admiration to Zola in response.

The Manifesto

Both Pissarro and Monet also signed the “Manifesto of the Intellectuals”, a pro-Dreyfus document that was circulated among students, publicists and other members of the Liberal camp, following the publication of “J’Accuse”.

4. Which Impressionist artists were anti-Dreyfus?

Edgar Degas was the most vehemently anti-Dreyfus impressionist.

But both Renoir, who made a number of anti-semitic remarks in private, and Cezanne took the side of the government.

Edgar Degas

Unequivocally anti-Semitic, Degas was pushed almost to breaking point by the Dreyfus affair. Julie Manet’s diary details the extremes of his bigotry, which at times would reduce him to tears of anger.

She writes of one evening when she paid a visit to his studio to invite him to dinner but found him in a "state against the Jews," so she felt obliged to withdraw, "without asking him a thing.”

Degas’ violent antisemitism can be traced back over at least a decade before the Dreyfus affair began. He was known for discussing antisemitic ideas with a close acquaintance, Maurice Talmeyr, who was also an ultranationalist journalist. Similarly, he kept up to date with the far right press and read La Libre Parole, a well-known French antisemitic newspaper.

In one case, Degas fired a model on the spot for expressing views related to Dreyfus’ innocence. He spoke of the event himself, describing how he asked, "You're Jewish yourself?” She replied, ”No, monsieur, I'm a Protestant." To which he said,

“Ah, you're Protestant. Well, then, get the hell out of here."

This particular anecdote was told to an audience of both Protestants and Jews at the home of Ludovic Halévy, a French author and playwright who was himself a Dreyfusard and of Jewish descent. Shortly afterwards, Degas broke off their friendship, despite having been close to Halévy for many decades.

Sadly, this is not the only example of Degas’ horrifying antisemitism. Similar episodes can be found peppered throughout his career, from comments about his models to snide remarks to Pissarro.

Auguste Renoir

Unlike Degas, there has been some debate around Renoir’s position on the Dreyfus affair. Accounts from the time describe him refusing to exhibit with Pissarro, saying

“Who? Me? Me exhibit with a gang of Jews and Socialists? You must be mad!”

On the face of it, this seems like clear evidence of Renoir’s viewpoint, but his son interprets this quote as an attempt to lead Degas on.

In his book ‘Renoir, My Father’, Jean Renoir attribute’s Renoir’s real motivation for missing this particular exhibition to him not wanting to be associated with Paul Gauguin, who was also taking part. In the past, Renoir had criticised the artist’s work, saying for instance that “his Breton women look too anaemic”.

Whilst this is a possible though tenuous explanation for Renoir’s reaction, Julie Manet’s diary reveals other anti-Semitic sentiments uttered by Renoir in private. In January 1898, Renoir is quoted as saying,

“[The Jews] come to France to "to make money, but the moment a fight is on, they hide behind the first tree. There are so many in the army because the Jew likes to parade around in fancy uniforms. Every country chases them out, there is a reason for that, and we must not allow them to occupy such a position in France.”

She also noted that Renoir “let fly on the subject of Pissarro, ‘a Jew’, whose sons are natives of no country and who do their military service nowhere”. Renoir goes on, “It’s tenacious the Jewish race. Pissarro’s wife isn't one, yet all the children are, even more so than their father.”

These phrases make difficult reading, but they seem to reveal Renoir’s true opinions on the matter. At the same time, Julie’s diary also reveals Renoir's fears of where the anti-Semitism in France would lead. She wrote that he worried the affair:

“might take the form of anti-Semitism among the lower middle class. He could envisage armies of grocers and similar tradesmen, wearing hoods and treating the Jews the way the KKK treated the Negroes”

In public, Renoir held the stance that, “People are either pro- or anti-Dreyfus. I would try to be simply to be a Frenchman.”

For Pissarro, Renoir and Degas’ opinions had a direct impact on him. Both men refused to talk to their friend or exhibit with him and they cut off all correspondence with him and his family.

Paul Cézanne

Having retreated to Aix, Cézanne had gradually become more Catholic, assuming the faith of his family and his youth. He kept company with staunchly Catholic, anti-Dreyfusard painters and writers and was himself convinced that Dreyfus was a traitor. However, Cézanne was far less outspoken than Renoir and Degas on matters related to the Dreyfus affair. When commenting on his one-time friend Zola’s actions he simply said, “they took him in”.

5. The effect of Dreyfus on impressionist art

For the artists weighing in on the Dreyfus Affair, it was almost impossible not to absorb some of the elements of the great debate into their work.

Those who were pro-Dreyfus continued to embrace modernity, whilst those who were anti-Dreyfus reverted to more traditional and classical subject matter.

For Cézanne, Degas and Renoir, the changing political fabric of France is indicated by their gradual turning away from the iconography of modern life that had once featured in the work of the Impressionists. Critics have interpreted this shift as evidence of a wider dislike for the modern world as a whole, a world seemingly populated by socialists, intellectuals, feminists, and Jews.

Degas and Renoir

As to how this attitude was reflected in their art, it is perhaps no coincidence that Degas and Renoir both turned to the female form for solace. Both men held a public dislike for women seeking to extend their outlook beyond careers as singers as dancers. Renoir described in 1888 how,

"I consider as monstrous women litterateurs, lawyers and politicasters, Georges Sand, Mme Adam and suchlike bores who are little better than longtailed sheep”

Similarly, Julie Manet writes of Degas’ opinions on the painter and diarist Marie Bashkirtseff as

“deserving of a public whipping.”

In the face of these educated women and new, liberal politics, Renoir and Degas turned to one of the icons of classical art, rooted in ideals of Christian, European beauty. Their nude works differed in their execution but not in the political motivations underlying them. For Degas, it was a voyeuristic, carnal interpretation of the female form, whilst Renoir assumed a classicising gaze, painting his subjects as voluptuous and angelic.

Cezanne

Meanwhile, Cézanne turned to nature in pursuit of an alternative subject to the modernity he saw encroaching around him. In a letter to his niece, written in 1902, he complained that

"Engineers ruin everything, it's a republic of flat straight lines. Is there a single straight line in nature, I ask you?”

In the following years, he sought out a divine form of nature, attempting to capture God’s handiwork through the lens of his new-found faith.

Monet and Pissarro

In contrast, Monet and Pissarro continued to paint rural themes but they also readily showed enthusiasm for modernity. Britain was a safe haven for pro-Dreyfus supporters and Liberals and during the early 1900s, Monet retreated often to London to paint. He depicted the bridges of the Thames and the Houses of Parliament as resplendent cathedrals, blushing in the soft tones of sunrise and sunset.

Despite the relative peace of these works, Monet was making a political statement. This period signals the end of Monet’s foray into patriotic themes. From this we can interpret that he became disillusioned with his native France during this time and the remorseless reactionary politics raging through the country.

6. The long-term impact of the Dreyfus affair on the Impressionists

The Dreyfus affair exposed a deeper crisis in Impressionism, one that had begun long before the staged trial of an innocent captain.

The once united group no longer held the same ideals, political or painterly, and each was moving in their own direction.

In the brash, busy modern Paris, complete with “dirty horseless carriages”, Degas, Renoir and Cézanne became increasingly nostalgic for a lost past. Pissarro looked to an anarchist, idealised vision of the future, in which everyone is equal and living in harmony. Monet, on the other hand, rode the wave of the political turmoil in France, part patriot, part republican and was ultimately able to come out on top.