1. The Grand Decorations

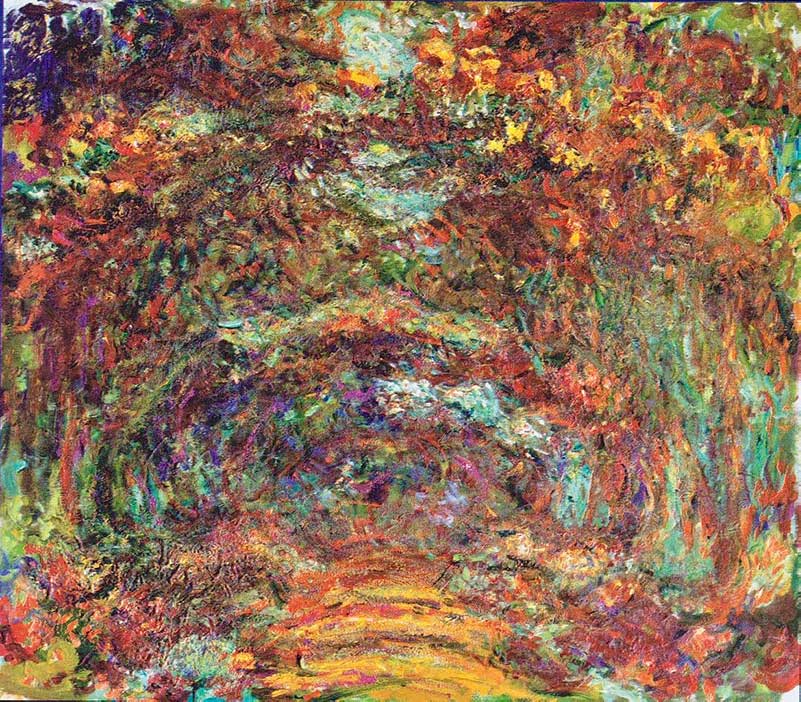

Claude Monet slaved over the eight water lilies displayed by the Musee de l'Orangerie between 1914 and his death in December 1926.

They are each 2 metres tall, and measure between 6 and 17 metres in length - making a total length of about 100 metres. Known as the "Grand Decorations", the paintings are affixed to the walls of two purpose-built oval shaped rooms, which are bathed in natural light on a sunny day.

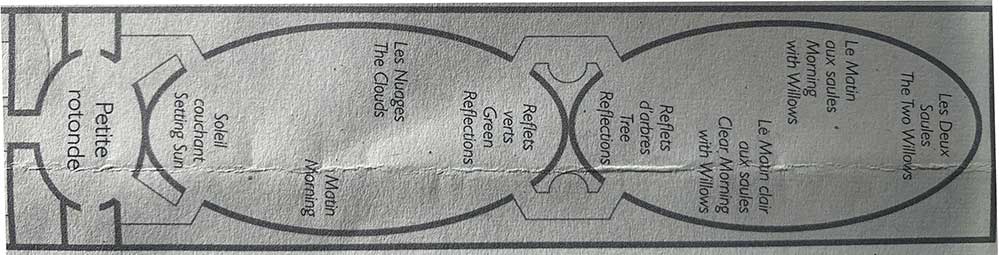

The eight paintings, and their sizes, are described in turn below. Paintings 1-4 are displayed in the first oval room; paintings 5-8 in the second.

(1) Waterlilies: Morning (2 x 12.75 metres, made up of four panels).

(2) Waterlilies: Clouds (2 x 12.75 metres, made up of three panels).

(3) Waterlilies: Setting Sun (2 x 6 metres).

(4) Waterlilies: Green Reflections (2 x 8 metres).

(5) Waterlilies: Clear Morning with Weeping Willows (2 x 12.75 metres, made up of three panels).

(6) Waterlilies: Morning with Weeping Willows (2 x 12.75 metres, made up of three panels).

(7) Waterlilies: Reflections of Trees (2 x 8.5 metres, made up of two panels).

(8) Waterlilies: The Two Willow Trees (2 x 17 metres, made up of four panels).

2. The painting of the Grand Decorations

The Grand Decorations are peaceful and serene. But the story of how they were painted is very different.

Monet's idea

Claude Monet moved to Giverny, a small village an hour north-west of Paris, in 1883. He was searching for tranquility and cheap rent. As time went by, and Monet started to sell paintings, he bought his Giverny house (1890), bought adjoining land to create water lily ponds (1893), and then - in about 1895 - started to paint water lilies with a passion bordering on obsession.

Monet painted over 300 water lilies in total, featuring his pond at different seasons, at different times of the day, and at varying levels of abstraction. They regularly sell for tens of millions of dollars.

But Monet produced nothing on the same scale as his Grand Decorations.

The agreement to donate

Georges Clemenceau, the French statesman and one of Monet's old friends, encouraged Monet to start painting a series of decorative water lily panels in 1914.

This was largely to help Monet take his mind off the death of his eldest son, Jean, earlier that year. Monet took Jean's death, at the age of 46, very badly: he was so depressed he couldn't bring himself to pick up a paintbrush.

Monet eventually started to paint again and mentioned the possibility of donating water lily panels to the French state on 12 November 1918, the day after the conclusion of World War One. He wrote to Clemenceau:

"It is not much, but it is the only way I have of taking part in the victory."

After much cajoling on the part of Clemenceau, including giving Monet carte blanche over the re-design of the Orangerie, Monet signed donation papers on 12 April 1922 - promising to deliver eight completed canvasses in April 1924.

But that date came and went. Rather than complete his donation, Monet insisted that his works were no good and that he would have to withdraw from the arrangement. Clemenceau provided reassurance and encouragement, and postponed the date for delivery. But Monet never completed the Grand Decorations to his satisfaction before his death in December 1926.

Tortured artist ...

There were all sorts of problems.

The first issue was on of practicality: the Grand Decorations were vast works of art. Monet had a third studio built at Giverny in 1916 to house them, measuring 23 by 12 metres. He also procured bespoke easels and trollies to assist in painting and moving the canvasses. His general modus operandi was to make large studies for the Grand Decorations during summer, and to work on the canvasses themselves during winter.

Then there was Monet's eyesight. It started to deteriorate in 1907, and Monet was suffering from cataracts by 1912. But Monet refused to seek medical assistance. By 1922, he was medically blind in one eye and had only 10% vision in the other - so he had no option other than to go under the knife. But it took Monet a long time to recuperate, in part because he was a terrible patient who wouldn't follow his doctor's orders.

Monet was also a perfectionist. As he once wrote to a friend:

"These water lilies have become an obsession for me. It is beyond my strength as an old man and yet I want to render what I feel."

When things weren't going well, Monet went into a sulk. And occasionally he even attacked his work, jumping on it, slashing it, and even setting it on fire!

To learn more about how the Grand Decorations were produced, we highly recommend Ross King's book Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the painting of the Water Lilies (Bloomsbury, 2016, 403 pp).

3. History of the Museum

The Orangerie in the Tuileries Gardens was first constructed in 1852.

It was used for a variety of purposes aside from growing plants for the Tuileries gardens - as a warehouse, an examination room and soldiers' barracks - before being assigned to the Fine Arts department of the French state in 1921 and earmarked to house the Grand Decorations.

Bad reviews

The Grand Decorations were installed shortly after Monet's death in December 1926, with the Orangerie opening to the public on 17 May 1927.

But it opened to largely hostile reviews, with many saying that Monet had lost his way artistically, that he hadn't moved on from impressionism, and even that Monet may have lost his marbles. For example, Jacques-Emile Blanches wrote:

"These spots, these splashes, these scratches inflicted on the surface of canvases of who knows how many square metres ... a theatrical set designer with his bag of tricks could succeed in producing much the same effect."

... and empty galleries

And then there was another problem: virtually nobody came to see the Grand Decorations. In June 1928, Clemenceau observed that there

"wasn't a soul there ... during the day forty-six men and women came, of whom forty-four were lovers looking for a solitary spot."

It got so bad that Monet's godson, Paul-Emile Pissarro, claimed that Monet had to be buried twice: once in 1926 after he died; and again with the opening of the Orangerie.

The reason was that art had moved on from Monet. By 1927, the world was excited about cubism, abstraction and expressionism. And so the Orangerie was used for other exhibitions ... and even a dog show (with the Grands Decorations hidden behind false walls).

As a further indignity, the Grand Decorations were damaged by allied bombing of Paris in August 1944.

To infinity and beyond

Things began to improve in the 1960s when New York's Museum of Modern Art re-popularised Monet. Rothko, Jackson Pollock and many other abstract expressionists were inspired by Monet and visitors started to arrive in their droves. These days, about 1 million attend each year.

The Grand Decorations are now displayed in two oval rooms constructed between 2000-2006. They seek to do justice to Monet's original vision: that visitors should not be able to tell when the cycle of water lilies starts and ends. Indeed, as the below plan shows, the two oval rooms themselves form the infinity symbol.

4. The Walter-Guillaume Collection

The Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume Collection was acquired by the Orangerie between 1959 and 1963.

It was donated by Domenica Walter (1898-1977), the widow of both Paul Guillaume (1891-1934) and then Jean Walter (1883-1957).

Highlights

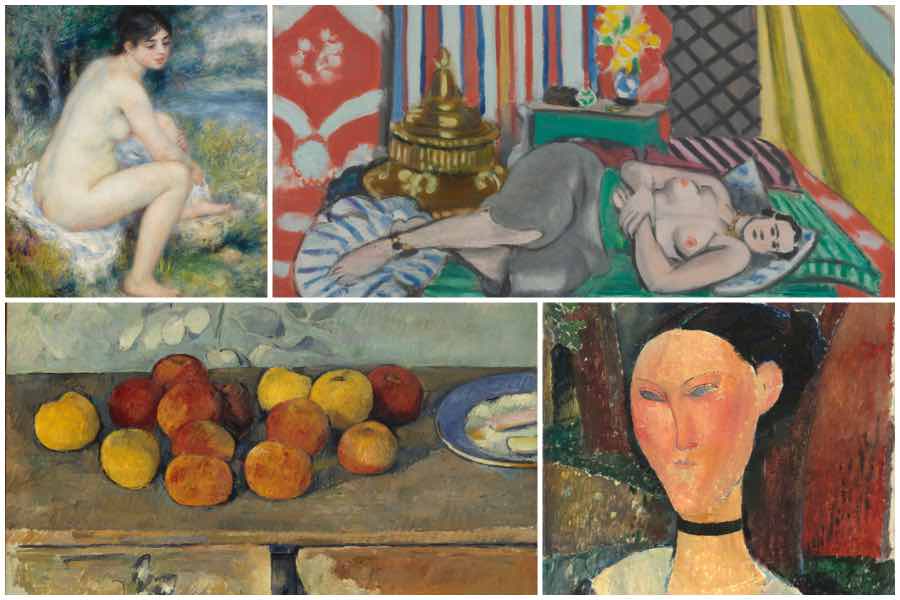

Displayed in the basement, the collection has some stunning pieces. They include:

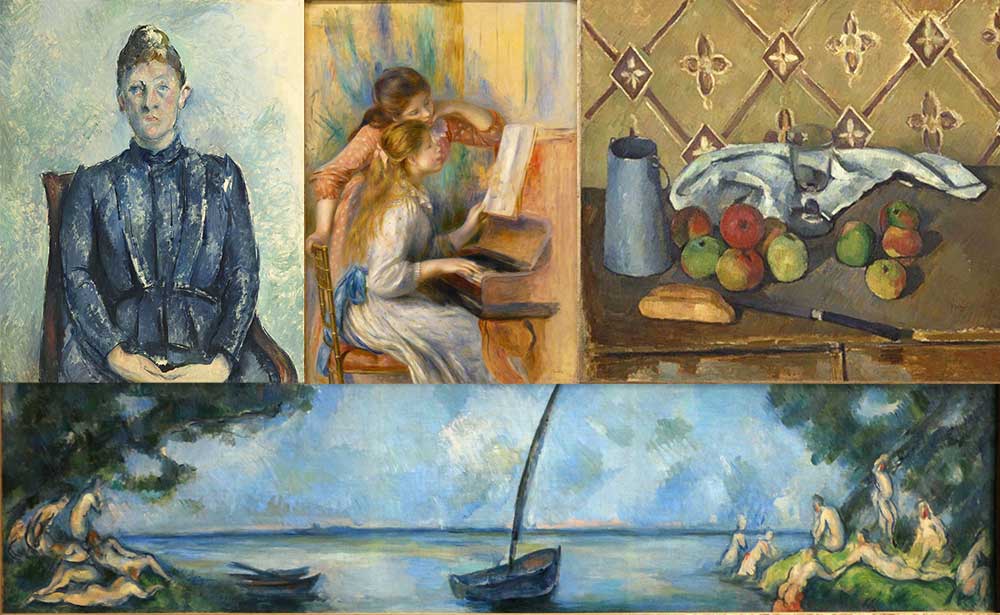

- Renoir's Young Ladies at the Piano (1892) and Naked Woman Lying (Gabrielle) (1906-1907)

- Cezanne's Portrait of the artist's son (1881-2), Portrait of Madame Cezanne (1890), The Boat and the Bathers (1890) and various still lifes.

- Modigliani's Woman with a Velvet Ribbon (1915).

- Picasso's The Embrace (1903) and Woman with a Tambourine (1925).

- Matisse's Odalisque in Red Pants (1924-5)

Temporary Exhibitions

The Orangerie hosts a number of high-quality temporary exhibitions, such as Hockney's A Year in Normandy (which recently closed in Feb 2022).

2025-26's exhibitions are as follows:

- From 30 April to 18 August 2025: Out of focus. Another vision of art, from 1945 to nowadays

- From 8 October 2025 to 26 January 2026: Berthe Weill. Art dealer of the Parisian Avant-garde

5. Practical Information

The Musee de l'Orangerie is open six days a week from 9am to 6pm, closed on Tuesdays.

The Monday opening is important: many museums, including the Musee D'Orsay, are closed on Mondays.

Tickets

Tickets cost EUR13 (full price) and EUR10 (reduced price), and include the Grand Decorations, the Walter-Guillaume Collection, and temporary exhibitions. Audio guides cost EUR5.

Address

The Orangerie is found in the Jardin Tuileries, 75001 Paris, France. The closest metro stop is the Tuileries (Yellow line / Line 1).

Other points

The Orangerie has a small gift shop and a small - and trendy - cafe.