1. The issue of age

The death of Édouard Manet in 1883 hit the artists of the Impressionist movement extremely hard. His passing was a stark reminder of how fleeting life could be and for many of the artists, it opened up deeply held fears surrounding ageing and death.

The year following Manet’s death, Edgar Degas wrote to his friend Henry Lerrolle saying, “If you were single, 50 years of age (for the last month), you would know similar moments when a door shuts inside oneself […] One suppresses everything around one and once all alone one finally kills oneself, out of disgust.” His words portray some of the pain and anguish that he associated with aging around this time.

These common anxieties were made worse by the swift rise of young artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who had pioneered a new art form that was taking Paris by storm. Their popularity and fame was a direct threat to the Impressionists’ long held title of chief experimenters in French art. As a result, inter-generational jealousies began to bubble to the surface.

The dealer of Impressionism

Paul Durand-Ruel, the Impressionists’ principle dealer, was also struggling financially during this period. Despite a series of one-man shows, Durand-Ruel had been unable to breathe life into the French market for Impressionist art. By the mid-1880s, his business was in serious danger of going under which spelled disaster for many of the artists who relied on him for financial support.

Insecurity turned to bitterness and many of the Impressionist artists began to turn on one another. The resentment surrounding middle age and the successes of the new generation of artists served to heighten weaknesses that already existed within the group. The air of discontent that had been building since before the final Impressionist exhibition reached a tipping point in the 1880s and the artists gradually withdrew into separate camps.

2. New artistic ambitions

In this context, many of the Impressionists began dislike the idea of modernity itself. Rather than depicting modern life, as they had long sought to do, the artists began to turn to nostalgia as a subject for their paintings.

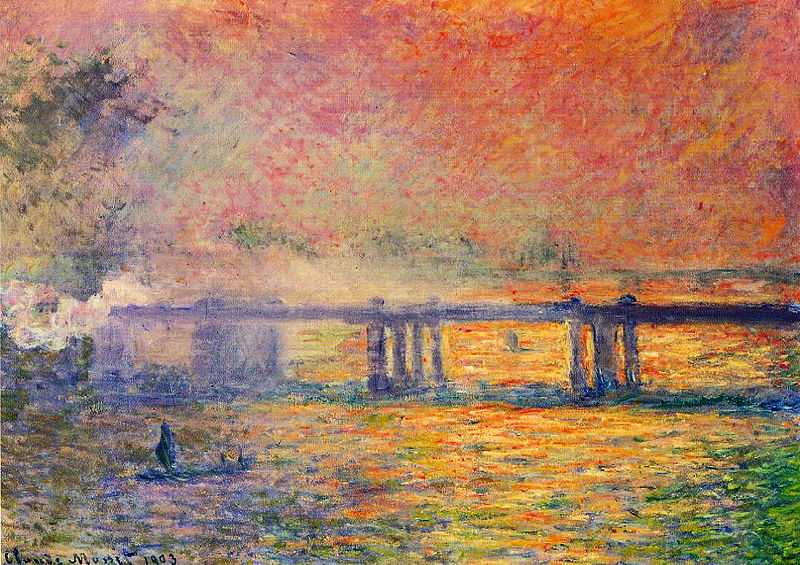

In the midst of these very human fears, we see a divergence in the artistic aims of the Impressionists. Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro became ever more committed to the Impressionist style. In fact, Monet was fast becoming a national symbol for the Impressionist movement. In 1899, he began his waterlilies series, which would go on to be one of the most memorable and most loved collection of Impressionist works.

Though Monet was unsettled by the changes he witnessed in France and he missed the Paris he once knew, he did not shy away from modernity. On several visits to London during the 1890s and 1900s, he painted the same city scenes that he had years before. He centred on the River Thames and the factories that lined its banks, as well as the stark, industrial bridges that had been built along it.

Like Monet, Pissarro also held firmly to the belief that Impressionism was the way to best wrestle with the issue of modernity. In his opinion, “The Impressionists have got it right, it is sound art, based on sensations, and it is honest”, he wrote in 1891. At the same time, he continued to keep close company with Signac and the new generation of artists who were moving forward with experiments of colour theory and optics in art.

Different approaches to Impressionism

In contrast, Auguste Renoir and Degas both began to pursue their own distinct paths, focussing in on the female form instead of the outside world. After he had visited New Orleans in the early 1870s, Degas had been filled with enthusiasm for depicting the new world in his painting. This energy and excited quickly began to dissipate in later life, however.

Instead, Degas sought to capture “simple, honest people” in his work, which led him to centre on female nudes. His image of the unsullied, unconscious woman came with large amount of condescension. He referred to his paintings of women as depicting “the human animal […] a cat who licks herself”. Rather than building on the Impressionist technique, Degas became more wedded to the work of the Neo-classical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Meanwhile, Renoir began to draw inspiration from the Renaissance for his nude paintings. His curvaceous female figures have been interpreted by some critics as a kind of nostalgia for his youth that had now passed. In his work, one can read the desire to stop time, to freeze his figures in a utopian vision of femininity and fecundity.

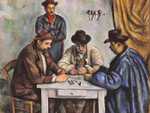

Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne became an iconic figure among symbolist painters and poets, who raised him up as their inspiration. This was partly motivated by an admiration of his new found piety, “the peasant in his Sunday best” as described by the poet Léo Larguier. His painting morphed into enormously expressive landscapes, inspired by Provence but also heavily shaped by the influence of Pissarro.

Manet's influence

For Berthe Morisot, the death of Manet was difficult to overcome. She struggled deeply with the loss of her close friend and artistic confidant and instead of painting, she absorbed herself in her social life. She all but stepped away from her profession as a painter in the years immediately following his death.

The Impressionist style as it once had been was at an end. Arguments around aesthetics drove the artists apart and there was no longer any read across between the different artworks, nor were there any united exhibitions in which comparisons between the artists could be made.

3. The changing geography of Paris

As well as the artistic fragmenting of the group, there was a literal fragmenting too as the artists moved out of Paris.

The Eighth and Final Impressionist Exhibition ended in 1886, closing the chapter on the Impressionists’ period of collaboration and collective identity. With the ending of the independent exhibitions, the Impressionists began to leave the city more frequently in search of rural subjects.

Instead of gathering in the suburbs of Paris, meeting in cafes and cabarets, many of the artists chose to relocate to countryside retreats. Cézanne to Aix, Monet to Giverny, Alfred Sisley to Moret, and eventually Renoir to Cagnes.

Pissarro was now of the few who remained in Paris. He focussed on painting the newly built grand boulevards of Haussman’s Paris in their quintessentially urban glory, using a splendorous Impressionist palette. Unlike many of the other artists in the Impressionist group, he was not disillusioned by the changes he saw around him.

The Paris Pissarro inhabited had changed dramatically since he was a student but he continued to spend his time in the centre of the artistic community. He spent many hours chatting with fellow artists in the Nouvelle Athènes neighbourhood, albeit among a far younger crowd than himself. Whilst he believed in the restorative value of rural life, he continued to have an interest in the avant-garde and the recent developments in science and art, which kept him rooted in Paris.

Gustave Caillebotte also remained in Paris but as he grew older, he slowly drew in on himself. Worn down by disagreements with Degas, he had gradually ceased contact with the many of the Impressionists. Nonetheless, he continued to paint en plein air in private.

For Caillebotte, the retreat from the Impressionist group had been caused more by attrition than any deep seated animosity. Despite years of financial and moral support, he no longer had the energy to fight for the cause.

4. Political rifts

The political beliefs of the group also contributed to the fractured ending of the Impressionist period, though this crucial factor is often missed.

Through the 1880s, many of the Impressionists had become increasingly politicised. For Degas, this had meant a movement towards to far-right and anti-Semitism. For Pissarro, the liberal and anarchist ideas that he had held since his youth became ever more relevant.

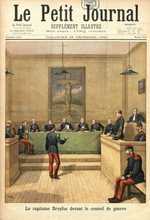

Political conflict within the group came to a head with the Dreyfus Affair. This event, involving the unfair conviction of a Jewish soldier, shook France to its core. The debates that sprung up as a result of the Dreyfus Affair divided the group with explosive consequences. Monet, Pissarro and Mary Cassatt were passionately pro-Dreyfus. Cézanne, Renoir and Degas were radically anti-Dreyfus.

The anti-Dreyfus camp cut ties with many of their old friends and acquaintances, distancing themselves from the salons and soirées where the Impressionists had once been regulars. They began keeping company solely with people who held their conservative, traditionalist views and ceased contact with the pro-Dreyfus Impressionists in the process.

On the other hand, Monet and Pissarro continued to cross paths as a result of their politics. They moved in circles with strong undercurrents of republican and anarchist beliefs. Though Monet had left Paris, he continued to stay informed of social and political life through close correspondence with friends in the capital.

The Dreyfus Affair revealed stark and irrevocable differences between the artists’ world-views. The group’s conflicting political ideologies had been there for some time, but they were laid bare by the reactions to the Dreyfus Affair. The anti-Semitic outburst that tore through the country in the years that followed did not spare the Impressionists. Sadly Pissarro, who was Jewish, was one of many people ostracised by his old friends, worst of all by Degas.

This event cemented the fate of the Impressionist period. Though the decline had begun as early as the 1880s, the Dreyfus Affair was an event that Impressionism was unable to recover from.

5. Impressionism in America

Though the 1880s spelt the beginning of the end for the Impressionist period in France, it also marked the start Impressionism’s rise in the US.

The popularity of Durand-Ruel’s ambitious exhibition in New York in 1886 demonstrated that there was market for Impressionist art in America. This had been helped in no small part by the efforts of Cassatt, who had been working for many years to encourage American collectors to recognise the value of Impressionism.

Sales of paintings from the exhibition were not enough to immediately reverse the finances of Durand-Ruel’s dealership but they were extremely promising. To avoid a tax on imported paintings, he moved the exhibition to another location. Not long after he organised a second exhibition in Manhattan.

In 1888, he opened the first American branch of the Durand-Ruel gallery, in an apartment at 297 Fifth Avenue. Durand-Ruel travelled back and forth between Paris and New York for the next few years, putting into place the building blocks of his new venture.

He later handed over the management of the American office to his three sons, Georges, Charles and Joseph. Durand-Ruel made his fortune at the age of 61, having remained forever faithful to his vision for Impressionism.

6. The final end of the Impressionist period

In many ways, the Impressionists were driven apart by external forces and things beyond their control.

On the other hand, it was also the work of internal, highly personal conflicts within the group that saw them break apart for good. Age, politics, artistic differences, and geographical separation all contributed to the end of the Impressionist period.

Impressionism had begun in Paris when it was still essentially a medieval city. The fin de siècle or the turn of the century saw modernity looming large over the city. The unstoppable force of the Industrial age had changed much of Paris beyond recognition and it was this rapid transformation that many of the Impressionists struggled to come to terms with.

In their art and in their lives the Impressionists wrestled with the challenges thrown up by industrialisation. Many of the artists rejected the political changes that had accompanied it, turning towards an increasingly traditionalist outlook on the world. Monet, Pissarro and Cassatt were some of the few who were able to ride the wave.

Manet was the first of the Impressionists to pass away, followed by Caillebotte in 1894. After the death of Manet and then her husband, Berthe Morisot was never really the same. She contracted an illness while nursing her daughter Julie and passed away in 1895. Sisley also died in 1899, entrusting Monet with the care of his two children, who by then were living in poverty.

Pissarro was lucky enough to achieve recognition in his lifetime, but he continued to believe that the Impressionists were “far from being understood”. He died in 1903, passing his artistic legacy on to his son, Lucien Pissarro. Cézanne followed just a few years later in 1906.

Though Degas was suffering heavily from the effects of old age, especially deteriorating eyesight, he continued to experiment with his art. He purchased a camera in 1895 and started photography, taking a special interest in mirrored reflections. Degas outlived many of his peers, dying in 1917. Similarly, Renoir was still painting on the day he died in 1919, with the brush placed between his arthritic fingers by his sons or servants.

From the original Impressionists it was Monet who endured the longest, both in his legacy and his life. He continued to paint from his home in Giverny, selling his works for high prices and participating in both solo and joint exhibitions.

Monet lived until the age of 86, passing away in 1926. His commission of water lilies, given as a gift to France the day after the armistice of 11th November 1918, were displayed in a dedicated gallery at the Musée de l’Orangerie in 1927 a few months after his death.

Cassatt died the same year, having continued to paint and exhibit her works long after the ending of the Impressionist period. Durand-Ruel organised two one-woman shows in 1891 and 1893, and a much larger exhibition dedicated to her work in 1895. She spent her final years living in Grasse, on the Riviera.