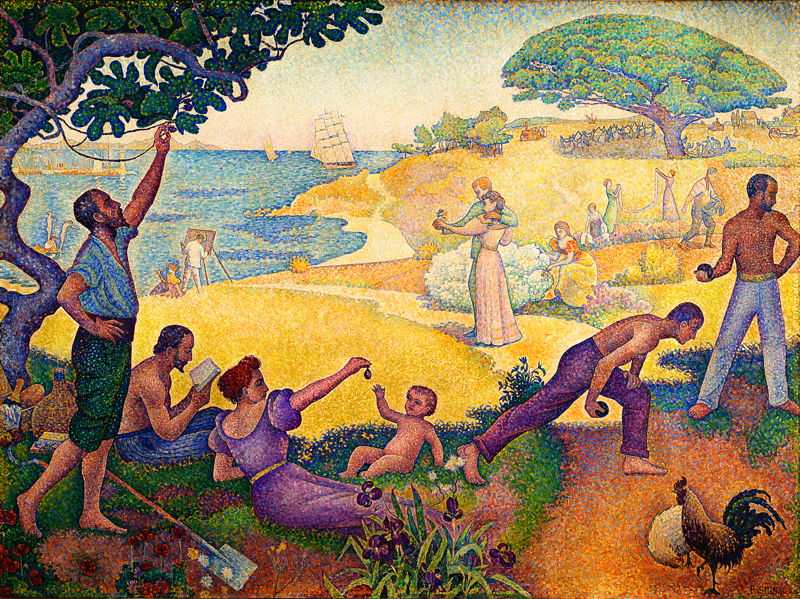

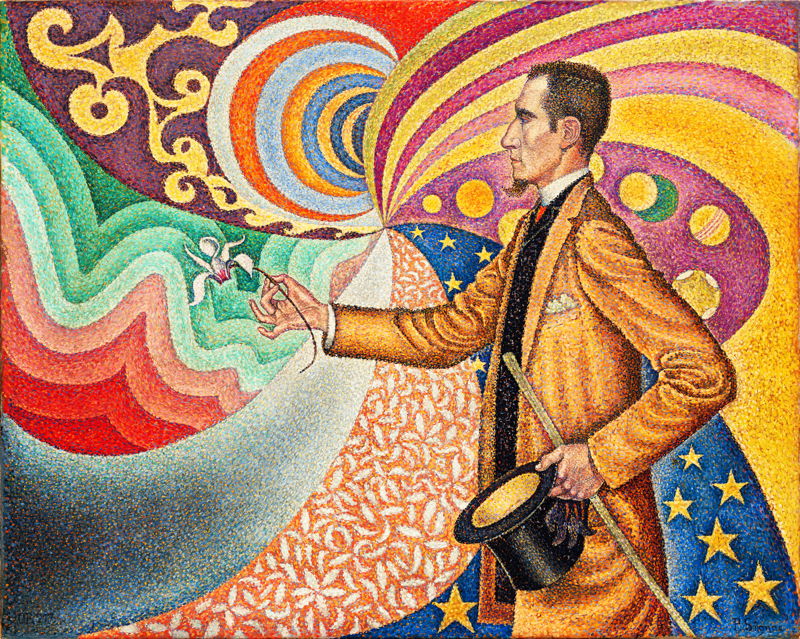

1. Portrait of Félix Fénéon (1890)

Neo-Impressionism or pointillism was considered the first example of avant-garde experimentation within Western art.

Born out of observations from younger artists towards their older peers, the movement was simultaneously a reaction to and a continuation of Impressionism. Characterised by meticulous brushwork and daring colours, Neo-Impressionism had its own, unique fingerprint. The art critic, Félix Fénéon, recognised this and subsequently coined the new term. Fénéon was heavily involved in turn-of-the-century activism, which is how his kinship with Signac formed.

For this portrait, Signac curiously uses a landscape format, which, along with his model posing as a magician, proposes that Fénéon was somebody who could command a wider audience. Painted in a side profile, Fénéon is strikingly set against a spiralling background, furthering the mystical symbolism. Inside the arabesque swirls, Signac includes his friend’s interests, such as adding stars to denote the American flag. From his hat, Fénéon plucks a lily to illustrate that Neo-Impressionism was in full bloom.

Another associate of Signac was fellow Neo-Impressionist Georges Seurat, with whom he founded the exhibition group ‘Salon des Indépendants’. Signac held Seurat in high regard, stating that he was the first artist to exhibit “the first separated painting”, a comment on Seurat’s distinctive style. In a ‘Portrait of Félix Fénéon’, Signac pays tribute to his idol via his own take on Pointillism, using thousands of tiny dots to make up the image. Some even say this particular portrait is reminiscent of Seurat’s final masterpiece, ‘The Circus’ from 1891.

2. Entering the port of La Rochelle (1921)

Sailing was a favourite pastime of Signac.

He began his travels by sea in 1892 during which he visited a plethora of French ports. In this rendition of La Rochelle, a scarlet sailboat takes position at the centre. The rippling water and ballooning clouds generate a mass of movement. The sky is especially dramatic, perhaps a homage to Johan-Barthold Jongkind, who was known for painting dynamic skyscapes. This would make sense since Signac stated that Jongkind was “the first Impressionist” after viewing ‘Bas Meudon Landscape’ (1865).

Furthermore, the combination of the Medieval tower and the pink puffs of cloud give the image a fairytale finish. This holds a certain irony as the Impressionists prided themselves on portraying raw, real-life scenes, rather than the religious and mythological scenarios that their predecessors preferred. It is perhaps unsurprising that the Impressionists felt so strongly about rejecting the blueprint of academic painting because their movement had been dismissed by the Salon. In a self-effacing quote, Signac said that the “the unexpected vividness” of Neo-Impressionist aesthetics “was immediately noticed, if not exactly welcomed”.

This painting is also an excellent showcase of Signac’s skill later in life. Building upon experience, his Pointillist brushstrokes became more precise over time. Using small dabs of paint, the atmosphere is constructed using contrasting colours to emphasise highlights and lowlights in the scene. This relates to Signac’s philosophy that in order to understand the “secret laws governing colour” you had to acknowledge “the harmony of similarities, the analogy of opposites”.

3. Sunday (1890)

Signac carefully planned this next piece between 1887 and 1889, making several preliminary studies, including a notable crayon lithography labelled ‘La Dimanche’.

At first glance, the picture appears cosy, presenting a couple and their cat going about their daily business in a charming Parisian apartment. However, he did not intend it to be quaint. A self-titled “anarchist painter”, Signac shows his distaste for the bourgeoisie lifestyle by deliberately placing the couple apart with their backs turned.

Moreover, his choice of colour, or lack of, helps portray monotony. It could be argued that the quality of light was affected due to this being a domestic scene. Conversely, given Signac’s standpoint, it is likely that this choice was made to exemplify how loveless and dull he believed the upper middle-class to be. Additionally, because this painting was made off-location in Signac’s studio, it creates a deliberate artificialness.

This use of darker tones is also a reference back to the Impressionists as the Neo-Impressionists tended to favour a lighter palette. Regardless, in 1899, Signac celebrated his forebears by urging his own movement to “pay homage to their precursors, and to emphasise, in spite of the differences, the common aim: light and colour” revealing how fundamental colour theory was to this period.

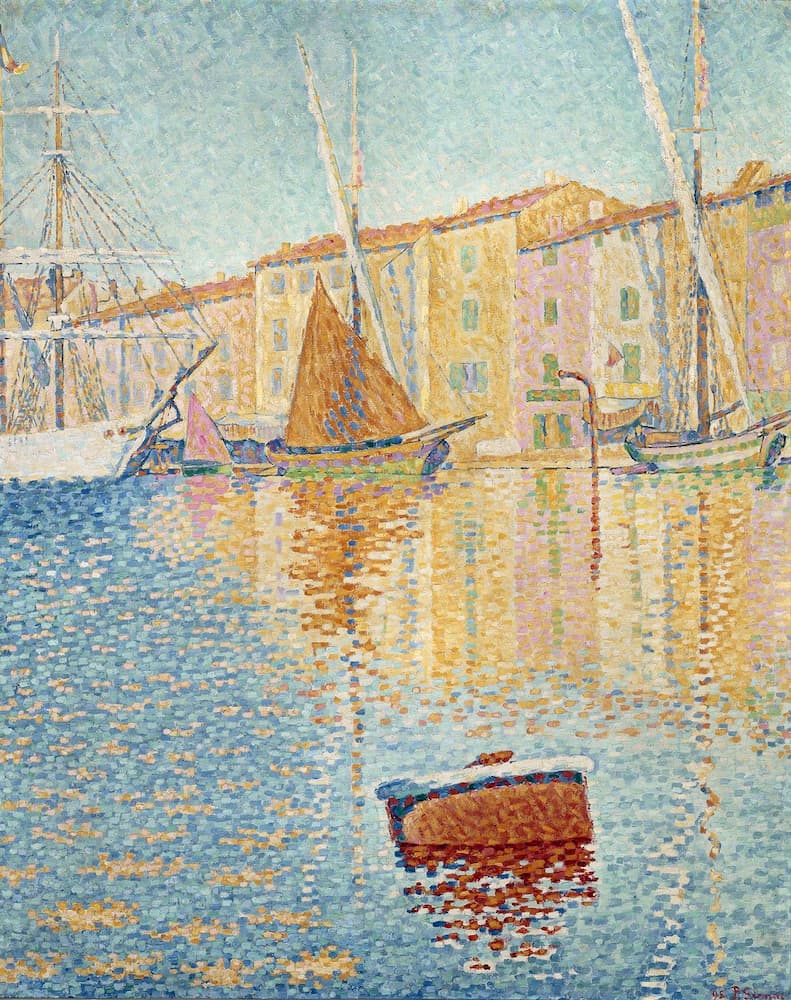

4. The Red Buoy (1895)

A vertical painting, ‘The Red Buoy’ uses lines and geometric shapes to create impact in this harbour scene.

Masts and sails travel upwards at diagonal angles, a technique that Signac used as a metaphor for joy. To emphasise this, he used baby blue, pastel pink and yellow gold in his palette, choosing that all “ascending lines are warm colours and clear tones”. While they are warm, the colours in ‘The Red Buoy’ are pale, showing the transition from the broody palette of the later Impressionists to the lighter visuals of the Neo-Impressionists.

The guidance of Seurat is also clear in this artwork. Signac takes the Pointillistic process that Seurat initiated and expands it. Signac’s colours are softer than Seurat’s and his brushstrokes are bigger in size. What’s more, he introduces half-tones which become a typical indicator of his work. This systemic style was called ‘Divisionism’. In his essays, Signac clarifies that “the Neo-Impressionist does not stipple, he divides … guaranteeing all benefits of light”.

Many followers of Seurat moved to the south of France to focus on maritime scenes. Signac was no exception, settling in Saint-Tropez around 1892. Seurat passed away only a year before, causing Signac to become the President of the ‘Salon des Indépendants’. He used this role to promote upcoming art movements, such as Fauvism and Cubism. In fact, the famed French Fauve, Henri Matisse, visited Signac in 1904. Signac’s patronage had a profound effect on Matisse’s own work. This greatly pleased Signac and he wrote, in 1899, that Divisionism “has not stopped developing”.

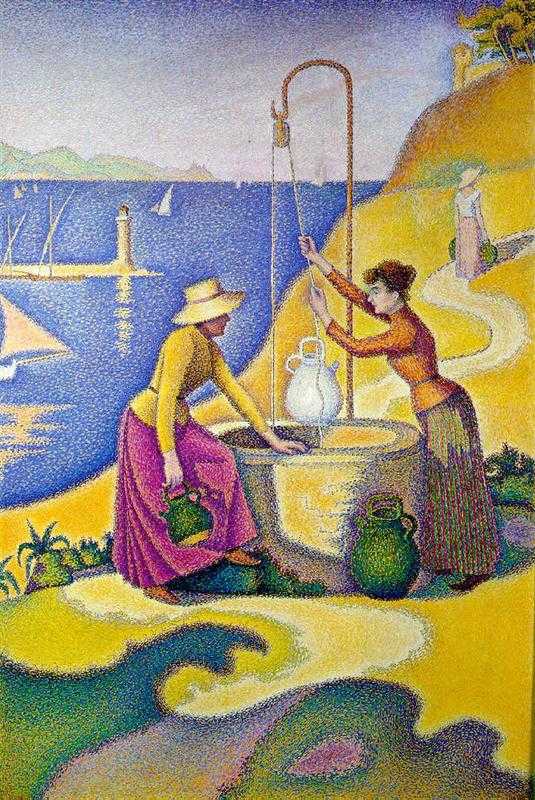

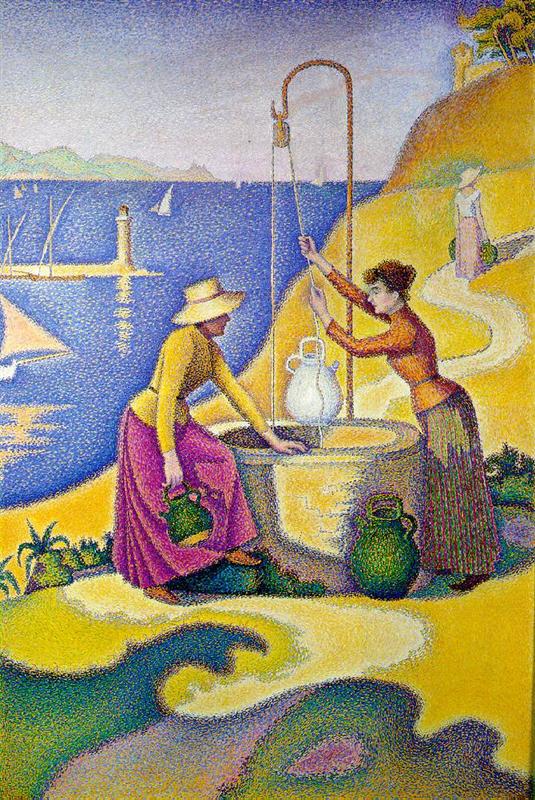

5. Women at the Well (1921)

Impressionists commonly painted candid pictures of modern life, with artists like Edgar Degas particularly leading this trend.

In this piece, Signac draws on this tradition, depicting figures peacefully collecting water in ceramic jugs. Meanwhile, the backdrop displays a tranquil ocean with tiny boats on the horizon. Solid, saturated colours give the illusion of heat from the sun. The image shows an ideal summer’s day.

Being an anarchist, Signac would have used these pictures of village life to highlight the happiness people can achieve away from the city and its classism. Here, ordinary citizens are immortalised through art, something which would have only been accessible to the aristocracy in the past. It is also a flashback to Medieval art, which celebrated the constant rhythm of rural life.

The nineteenth-century notion of painting outside, nicknamed ‘en plein air’, was popularised by Theodore Rousseau and rapidly became a tradition. A critic of the movement, Théodore Duret, remarked that “the Impressionist sits on the bank of a river and paints that which he sees before him”. The reason that open-air painting engrossed the Impressionists so much was because they found the experience of painting itself to be equal to the final product.

6. Snow, Boulevard de Clichy (1886)

One of Signac’s earlier endeavours, this snow scene is a snapshot in time.

Painted during the artist’s years in Paris as a young man, it shows pedestrians walking across wintry roads. The trees, constructed using only greys and blues, fade into the backdrop and manifest a sense of distance. The way their branches splay looks almost ghostly, however Signac makes certain that the picture remains homely with flourishes of red to warm the otherwise cold setting.

During the 1880s, the Montmartre district acted as the epicentre of the Impressionist movement. Consequently, the period that Signac spent in the French capital was critical to his work. Furthering this, Signac declared that the moment he “decided his career” was after visiting a Claude Monet exhibition in 1880. He even sent a letter to Monet in the same year, writing, “I have been following the wonderful path you broke for us”.

With varied brushstrokes and a sparse palette, the inspiration Signac took from Monet’s work is clear. A feature which demonstrates this is the snowfall itself: instead of relying on just white, Signac mixes in subtle pinks, yellows and blues. The individual colours are faint but when dappled together, they suggest texture. With beige added atop to depict the tracks left by vehicles and people, the viewer can follow the figures through the scene as if they were there.

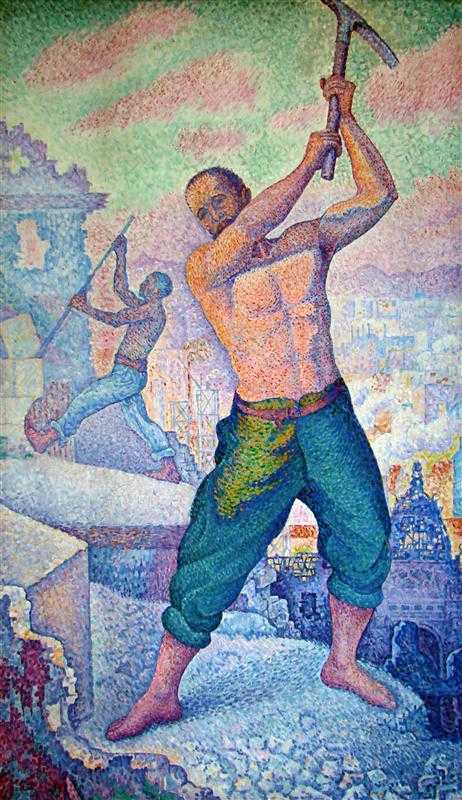

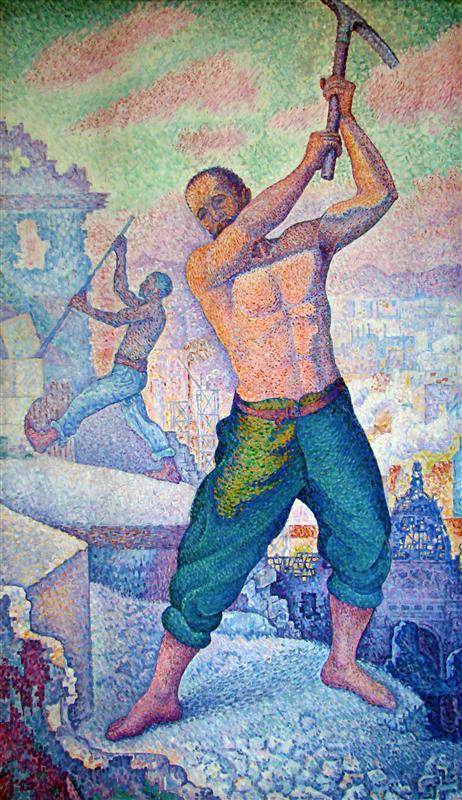

7. The Demolisher (1899)

Leading on from the last painting is another of Signac’s works set in Paris.

This time the artist chose to show the industrial side of the city. In the foreground are two male figures with tools raised above their heads, chipping away at the stone of a derelict building. Both men are bare-chested, an uncommon occurrence in an era which was dominated by female nudes. What’s more, the model behind is dark-skinned, no doubt a social comment by Signac about the abuse of immigrant labour.

Although a History painting, there is an anarchistic undertone to the work that is characteristic of Signac. At the bottom right is the skeleton of Notre Dame. At the front, the worker holds a pickaxe the way that a soldier grips a sword. This is undeniably an anti-establishment piece. Signac supports this theory in the quote, “The anarchist painter is not the one who will create anarchist pictures, but the one who will fight with all his individuality against official conventions”.

It is worth noting that the treatment of the Neo-Impressionists may have triggered their anarchist politics. After decades of the art world being led by elitist societies, such as the Royal Academy, the Impressionists were forced to organise their own exhibitions after their work failed to be selected by the establishment. They pushed past convention, helping to evolve not just the social structure of the industry, but also the aesthetic of the art itself. This work by Signac is one example of such breaking with conventions that the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists became known for.

8. Breeze, Concarneau (1891)

Once again hinting at Signac’s love for sailing, this seascape shows a fiercely competitive regatta.

Huge racing yachts blow in the breeze, their sails set at dynamic sloping angles. The illusion of movement is impeccable in this piece. Signac’s brushwork is miniscule: he paints singular dots, darkening colours to create shadow. With each line of waves, he lets the natural colour of the canvas slip through.

This technique of applying multi-coloured dots is known as Divisionism. The process was coined by Seurat, who developed the style out of Pointillism. Divisionism differs slightly from the former technique: instead of connecting juxtaposing colours, the Neo-Impressionists used mid-tones. This method, when paired with distance, deceptively joins the dots, forming a complete image. This technique was known as “optical blending”. It was the very reason why Divisionism rocked the boat as, unlike anything before, it relied on the onlooker’s participation to create the full effect of the piece.

Signac was passionate about this new found system, hailing it as “an aesthetic rather than a technique”. In his attempts to promote it, he became the first ever foreign artist to join the Belgian group, ‘Les Vingt’. Signac also continued to refine his own talent and his later artworks presented dotwork on an almost cellular level. Signac paralleled this precision to the sciences, saying “the colourist has in some ways elements of mathematics”.

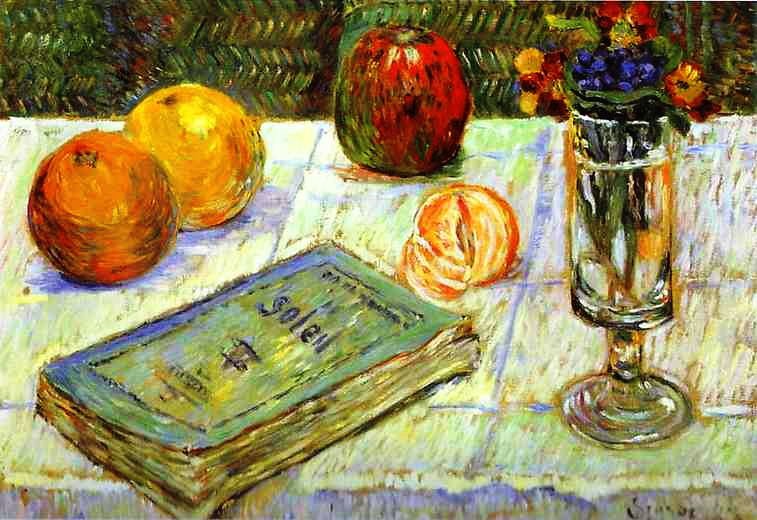

9. Still Life with a Book (1883)

An observational study, this painting reveals the trials and tribulations of Signac’s practice prior to adopting Divisionism.

The impact of the Impressionists is very present in this work, which is unsurprising as during the 1880s Signac was in the process of moulding his own style from Claude Monet’s. In a message penned to Monet, he wrote, “my only models have been your own works”.

Here, Signac’s tribute to his hero is most evident in the line art. Utilising long and rough brushstrokes, Signac builds up the image with generous amounts of paint. This technique differs in comparison to his later works, demonstrating his professional progression during this period.

When it comes to composition, each object in the still life is thoughtfully placed. It is likely that the youthful Signac purposefully did this to help hone his aptitude for painting negative space. It also lets each element have the limelight. At a slant, the book is offset, creating an angular bottom corner of the canvas. Comparatively, the roundness of the fruits creates naturalistic curves. This differentiation between shapes adds more flavour and flair to the overall work.

Colour theory was central to Signac’s values and in his most famous essay of 1899, he mentions Eugène Delacroix as an innovator of colour science. Delacroix was famed for creating darkened backgrounds of blues and greens while highlighting the main motif using vivid red. Signac imitates Delacroix’s tactics in this still life.

In the same text, Signac also ponders whether the Neo-Impressionists would have been better understood “by the epithet ‘Chromo-Luminaristes’” due to the abundance of colour in their work.

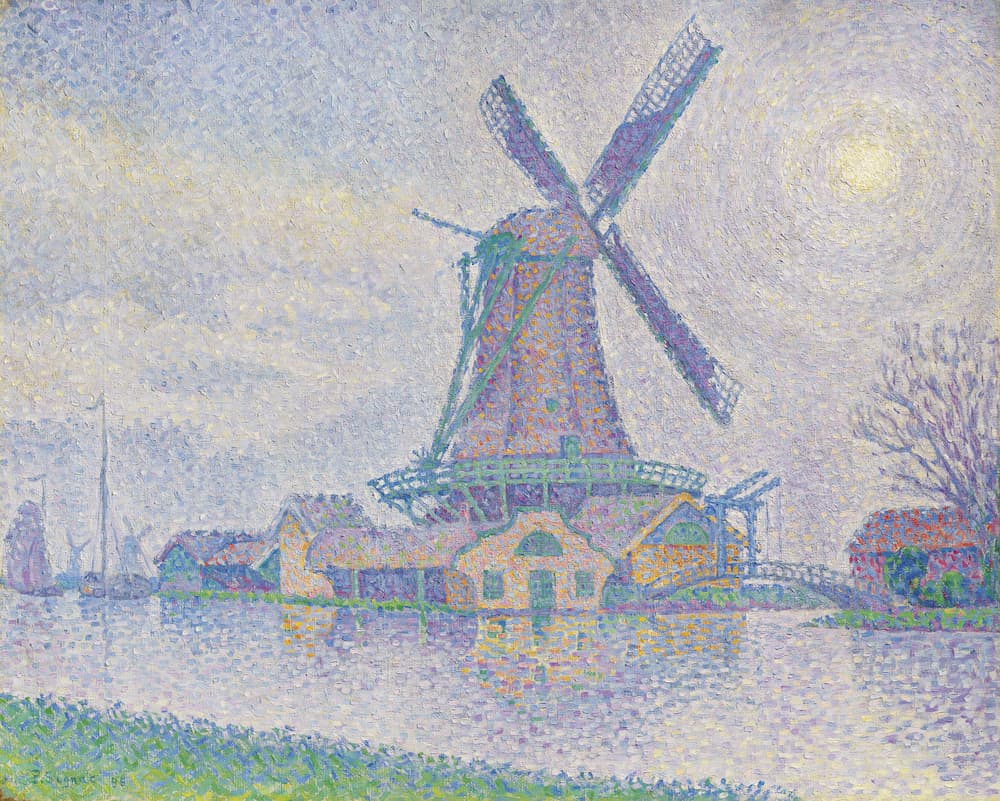

10. Windmill, Saint-Briac (1885)

The final painting in this list ironically references back to Signac’s teenage years.

An image of a mill, this painting draws on his earliest experiences with a brush. Before becoming a painter, he had trained as an architect. Here we can see his formal education excel in this picturesque landscape.

Pastel-coloured paint surges across the sky in mottled streaks, a complete contrast to the smooth blocks of brown used to create the buildings. The rosy light travels to the right, glowing against the bricks. It is quiet, simplistic and atmospheric.

During the 1800s, there was a shift in the locations favoured by artists. After centuries of the Italian and English countryside dominating canvasses, the Impressionists brought about a fresh appreciation for French and Dutch geography.

On his ventures around Western Europe, Signac met a handful of emerging painters, including Vincent Van Gogh. Van Gogh and Signac went on painting excursions together and this landscape is likely from one of their trips.

This panorama also brings to attention Signac’s interest in Naturalism. A popular philosophy of the nineteenth century, Naturalism was the belief that only organic forces, rather than spiritual ones, are what shape the Earth.

The musings of Émile Zola were endorsed by the Neo-Impressionists, specifically Signac and Hippolyte Taine. You can see the direct effect of such literature in this piece, which is poetic in its appearance.