1. Olympia the Painting

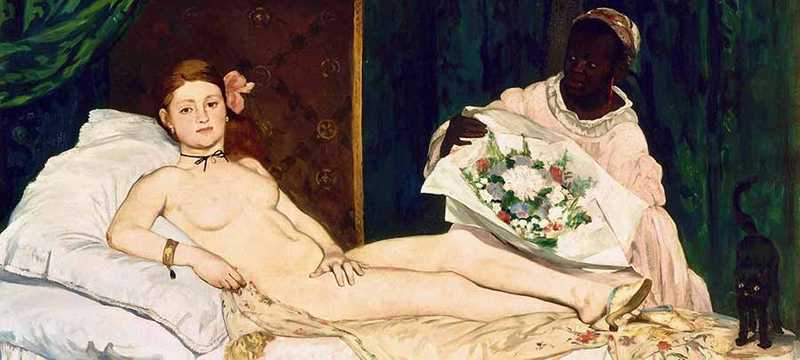

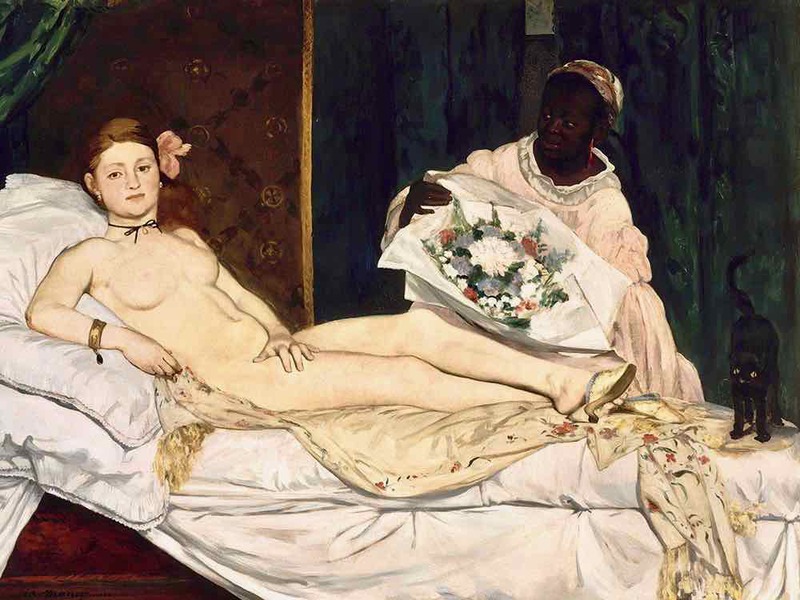

Painted in 1863, Olympia is a 130 x 195.5 centimetre oil on canvas painting now found in the Musee d'Orsay in Paris.

The painting depicts Victorine Meurent, one of Manet's favourite models, naked and staring brazenly from the canvas.

Read on to discover the background, inspiration and key features of Manet's controversial work.

(1) Background: Dejeuner sur l'Herbe

Born into a wealthy family in 1832, Edouard Manet had been on the Paris art scene since the late 1850s.

By the time he painted Olympia, Manet had a reputation as a rebel who refused to paint the religious, mythological and historical scenes favoured by conservative art establishment.

This reputation largely stemmed from Manet's 1862-3 work Dejeuner sur l'Herbe (Luncheon on the Grass).

Dejeuner sur l'Herbe is an odd composition. For example: why are the men dressed while the woman in the foreground is naked? what is the woman in the background doing? what happened to the picnic? You can learn more about it on our Top 10 Paintings page.

For now, however, the key point is that it got the public thinking and talking about Manet.

(2) Inspiration: the Venus of Urbino

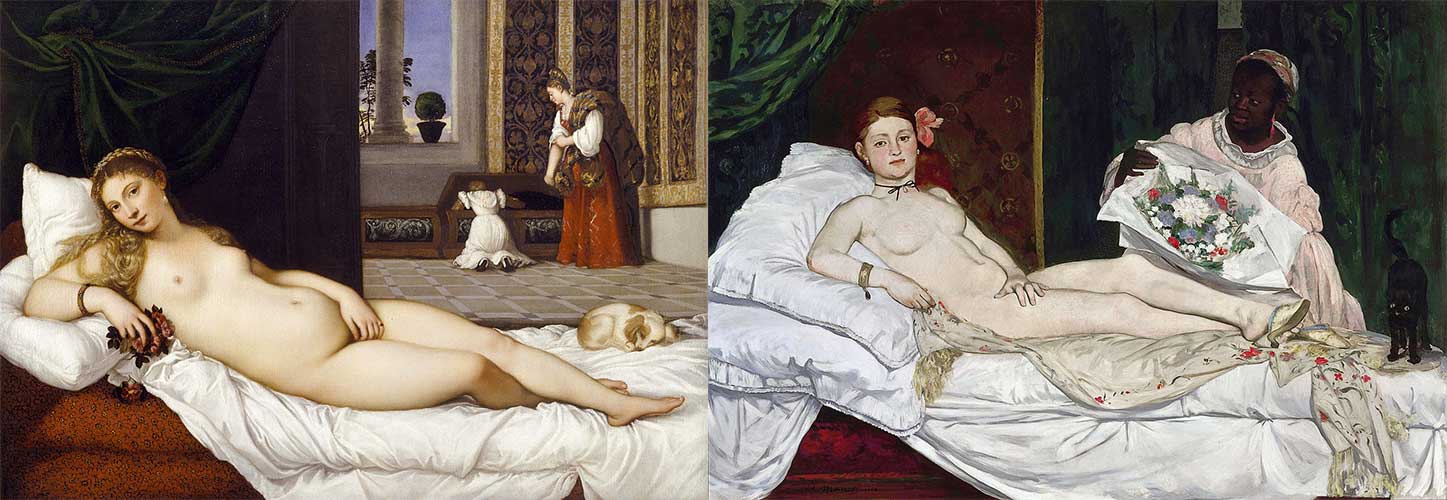

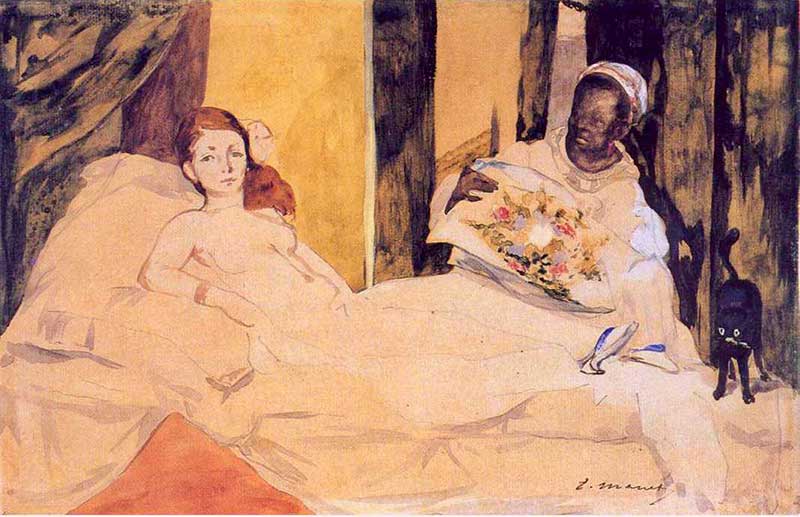

Manet’s composition of Olympia plays on the famous Renaissance painting The Venus of Urbino by Titian (1490-1576).

Titian’s work depicts Venus, the goddess of love, painted both as an erotic figure but also as a symbol of marital fidelity.

The similarities between the two works can be seen below:

But there is one BIG difference between the works.

In Titian's work, the dog at the foot of the bed, the roses in Venus' hand, the servant in the background looking down at the child, and the myrtle on the windowsill, all serve as symbols representing marital values such as faithfulness and motherhood.

In Manet’s painting, these symbols are turned on their head. The eroticism he presents could not be further from marital fidelity. Instead, it is rooted in lust, lasciviousness and prostitution.

(3) Can we be sure that Olympia is courtesan?

There is little doubt that Olympia was a prostitute:

- The black cat was a symbol of nocturnal promiscuity at the time, painted with eyes wide and tail raised.

- This orchid behind Olympia's ear has been associated with sexuality thanks to its large protruding pistil and its reputation for transience. It may also have marked Olympia out to be a creole woman, which at this time held the stereotype of passion and sensuality.

- The the black ribbon around Olympia's neck and the oriental shall on which she is lying are all symbols of sensuality and wealth.

- The name Olympia was associated with prostitution at the time.

(4) The scene

The Olympia scene is also full of meaning:

- Olympia lies on a fringed bedspread, her fingers playing with one end. Some commentators think this is an allusion to the model’s pubic hair.

- The slippers on the model’s feet, partly falling off, may also refer to the term ‘chausson’ (slipper) which also meant an “old prostitute”. The French phrase “putain comme chausson” means “whore like a slipper”. In contrast, Venus’ feet are bare and shapely, positioned demurely on the couch.

- The flowers in the scene also contribute to the overt sexuality in Manet’s painting. In the scene, Olympia is being presented with an open bouquet of flowers, another sexual symbol, wrapped in cheap newspaper rather than rooted in a pot.

(5) Olympia's maid

Whilst critiques have often tended to focus on Olympia herself, it is also important to dwell the other character in the painting.

The black woman standing over Olympia offers Olympia a bouquet of flowers, likely from a lover who is waiting just outside the scene. According to Sander Gilman, during the 19th century the image of a black woman in art was a convention for representing unbounded sexuality.

At the same time, the figure of Olympia’s servant disappears somewhat into the background. Manet’s light effects deliberately obscure her face, making her presence almost a suggestion. In contrast, the flowers are lit brightly, forcing them into the centre of attention like Olympia herself.

More recently, the painting was renamed ‘Laure’ by the Musée d’Orsay in recognition of the black model who also appears in the painting with Meurent. The 2019 exhibition sought to bring attention to the figures who have been ignored in art history. Indeed, Laure has often been missing from analyses of the work.

(6) Lighting

Finally, it’s important to note the unnatural lighting Manet uses in the scene.

Olympia’s face is lit up as though by a spotlight whilst the background is shadowy. Similarly, her face, neck and the flower in her hair are fully illuminated but the rest of her hair and body is not.

In manipulating the lighting in such a way, Manet was able to draw attention to a few key features in the painting: Olympia's face and her hard gaze.

2. The reaction

Manet’s Olympia was exhibited in the Paris Salon of May 1865.

The reaction to the painting was unprecedented. Press and critics instantly took against the work with cries like “Such indecency!” and contempt at the model’s “vicious strangeness”.

Hostility

One of the most extreme and famous reactions was published in Le Grand Journal by Amédée Cantaloube:

“... this Olympia, a kind of female gorilla, a grotesque in rubber outlined in black, apes on a bed, in a state of complete nudity, the horizontal attitude of Titian’s Venus: the right arm rests on the body in the same fashion, except for the hand, which is flexed in a sort of shameless contraction.”

This reaction echoed another review published in Les Tablettes de Pierrot describing:

“a woman on a bed, or, rather some sort of form bloated like a grotesque in rubber; a kind of African monkey [guenon] making fun of the pose and the movement of the arm in Titian’s Venus, with one hand shamelessly flexed.”

Félix Deriège in Le Siècle stated,

“She does not have a human form. Mr. Manet has so pulled her out of joint that she could not possibly move her arms or legs”.

Jules Claretie also asked,

“What is this odalisque with the yellow chest, an ignoble model picked up who knows where and who has the pretention to represent Olympia?”

Art historians have since linked adjectives such as ‘grotesque’, ‘monstrous’, ‘vulgar’ and ‘hideous’ to Olympia’s overt role as a prostitute, which the Parisian public were unable to refer to freely in polite society. As a result, they used exaggerated phrases to highlight their discomfort.

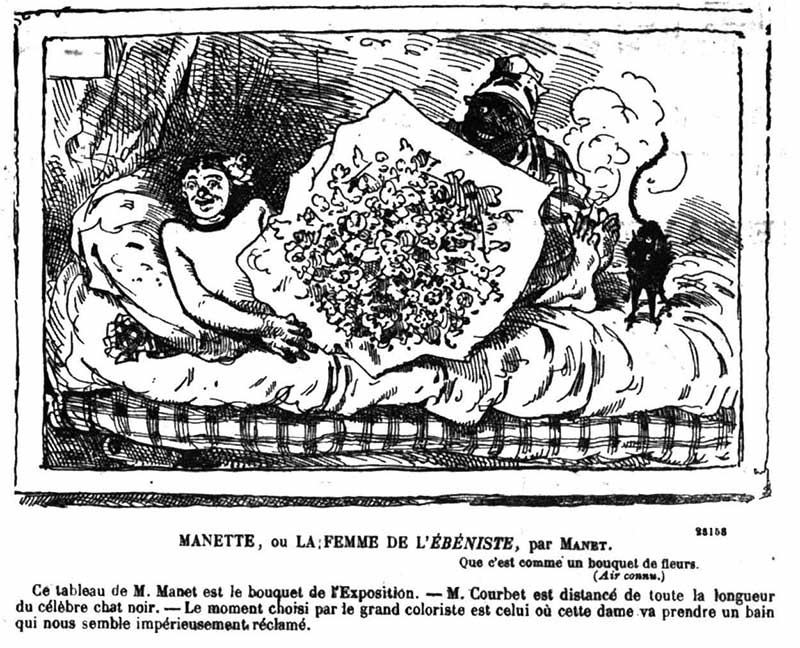

Cartoons

Manet was also ridiculed in cartoons. Here's an example:

A rough translation of the caption reads: "Manet's The Cabinetmaker's Wife. ... The moment chosen by the great artist is when the lady is about to take a much needed bath."

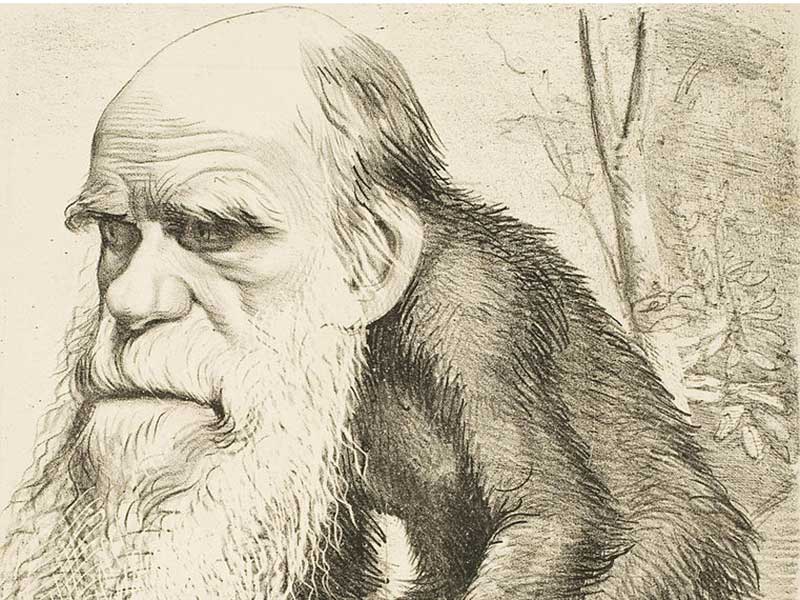

Darwin?

Art historian Anne McCauley has written on the use of the word "gorilla" to criticise Olympia. Her theory runs something like:

- In the mid-1860s, the educated classes were undergoing a crisis of faith: Darwin's On the Origin of Species had been published in 1859, and represented a huge challenge to conventional religious beliefs. Darwin's evidence that humans descended from monkeys was just not compatible with what the bible says about the creation of man.

- As a result, many people lashed out at Darwin (as can be seen from the below cartoon)

- The term 'gorilla' was therefore a popular and serious insult at the time, implying that Olympia’s ambiguous hand positions and uncontrollable sexuality brought her closer to a ‘gorilla’ than a bourgeois woman.

Indeed, Victor Fournel, writing in La Gazette de France described his experience of viewing Manet’s painting as like going to a fair, where

“a distinguished monsieur offers you, with elegant language, marvels that are extraordinary, incomparable, and unique, and then, as soon as you go inside, people show you a two-headed calf, one of which is cardboard.”

Laughter, confusion, outrage ... and hypocrisy

As well as confusion and outrage, the painting also prompted laughter. Some viewers even suggested that the work was a joke or was painted as a publicity stunt. There was a belief that Manet may have painted his strangely proportioned nude to try and draw a crowd.

Despite the outraged reactions of the crowd, it is also possible to see through the feigned horror that the critics portrayed. Whilst viewers may have been shocked by the immorality of the painting on display, many of the male attendees would also have had relationships with prostitutes, likely on a regular basis.

Many more would have viewed nude photos, visited brothels and purchased early pornographic images. As Charles Baudelaire pointed out in reference to another Salon work in 1859 that caused a similar stir, the prudishness of the public was nothing more than a front.

Amazingly, there were attempts to destroy the work by viewers using umbrellas and walking sticks. As a result, the Salon organisers were forced to move the painting higher up so that it was out of reach and out of harm’s way, as well as employing guards for the painting.

This was one of the strongest reactions to a work of art in modern history.

3. Olympia Today

These days Olympia is found at the Musee d'Orsay.

But the story of how she got there is interesting.

Olympia's first sale

Despite its notoriety, Olympia did not sell during Manet's lifetime (perhaps because Manet's price was too high). It therefore passed to Manet's widow, Suzanne, following Manet's death in 1883.

In the late 1880s, Monet organised a public collection to raise 20,000 francs to buy Olympia from Suzanne for the benefit of the French state. It is a sign of Monet's close friendship with Manet that he spent months organising the public collection, and sent hundreds of hand-written letters.

The money was duly raised and Olympia donated to the French state in 1890.

Getting Olympia into the Louvre

But Olympia was still extremely controversial. And the politicians and art administrators of the day refused to hang her in The Louvre, the inner sanctum of French art. Instead, Olympia was consigned to the Musee du Luxembourg, at the time devoted to contemporary art.

It was not until 1907, and the intervention of newly-invested French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, that Olympia was finally hung in the Louvre.

Interesting fact...

Clemenceau had been a close friend of the impressionists before he came to power. Indeed, Manet painted two portraits of him in the late 1870s.

And again to the D'Orsay

Olympia, together with all other impressionist works, moved again in 1986 when French art produced between 1848-1914 was transferred to the Musee D'Orsay.

Olympia is now found in Room 14 (on the ground floor), one of 47 works by Manet displayed by the museum.

4. Manet increases his influence

The notoriety that Olympia gained when it was unveiled catapulted Manet to fame among the Parisian elite.

He was quickly established as the leader of the avant-garde and artists and writers began to follow his work more closely.

Inspiring the impressionists

For the young impressionist artists, Edouard Manet became an ideal for what they hoped to achieve.

Part of Manet’s success came from the way he played with the sensibilities of his audience. He understood the drama that would be caused by his Olympia painting, though it is unlikely he had expected such an extreme reaction, and he used this to cultivate his artistic reputation in Paris.

For the Impressionists, the example Manet set gave them the space to also consider how they could break out of the mould of the artistic conventions in France at this time. Manet had begun to paint ordinary people, who existed in real life.

As Zola wrote in 1867:

“Here in the flesh is a girl whom the artist has put on canvas in her youthful, slightly tarnished nakedness […] He has introduced us to Olympia […] whom we have met in the streets”.

Manet’s work inspired the Impressionists to seek out their own subjects among the people on the streets of Paris.

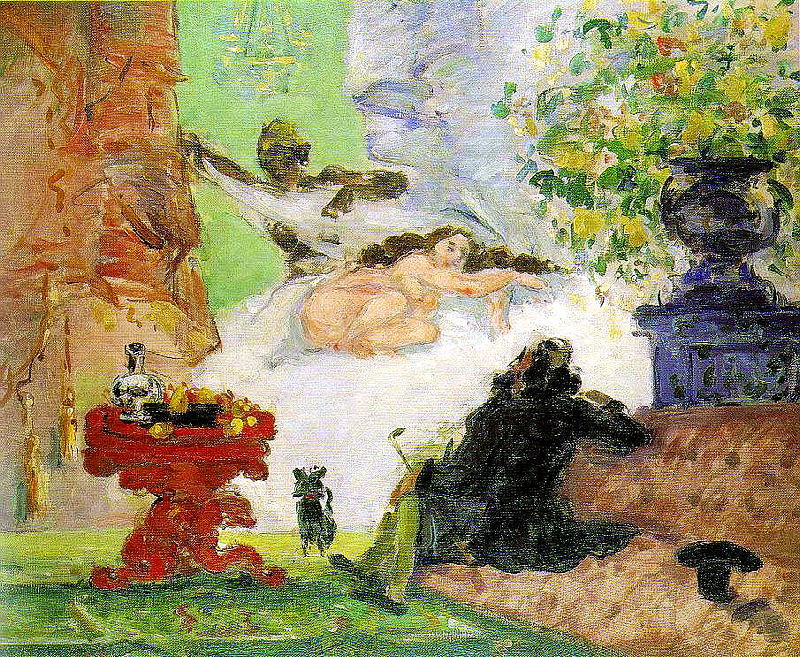

Cezanne's A Modern Olympia

One of those who sought to pay homage to Olympia was Paul Cezanne, who produced a work entitled 'A Modern Olympia' in 1874.

Now, I love Cezanne, but this is a really weird painting. Olympia seems to be lying on a cloud; I have no idea what the maid is doing; and the table in the foreground seems to be melting. One critic wrote that Cezanne was a

“sort of madman, painting in a state of delirium tremens”.

Agency of women

It is also important to note that Manet set a precedent for exploring women as agents in their own right in contemporary art.

He did away with traditional depictions of passive women and instead gave them more active roles. Many of the Impressionist artists returned to this image, albeit in less overt ways. This represented a turning point in French art.

Whilst Manet joined the impressionists in their aims to create a new art form, he did so on his own terms. Manet also wanted his work to be exhibited in the Salon and to achieve formal recognition. He was not content to be exhibited in independent exhibitions with the rest of the Impressionists.

This aspect of his career set him apart from the other artists in the movement throughout his life.

5. Victorine Meurent as Olympia

The model for Olympia was Victorine Meurent.

Manet painted Meurent a total of nine times between the years 1862 and 1874.

Manet's muse

As well as Olympia, Meurent also featured in the equally bold painting ‘L’Dejuner sur l’herbe’ from 1862-63 in which she poses naked next to two clothed men.

Meurent appears again in ‘Mademoiselle V. . . in the Costume of an Espada’ (1862) and ‘Woman with a Parrot’ (1866), as well as ‘The Railway’ (1873) with a penetrating gaze in every piece.

Manet meets Meurent

It is not clear how Manet and Meurent met.

Different sources have come up with various stories, from the two becoming acquainted at a printer’s studio to a meeting through Manet’s teacher Thomas Couture, for whom Meurent was also modelling.

A more colourful account, according to Théodore Duret, describes Manet spotting Meurent at the Palais de Justice (the law courts!) where he

“was struck by her unusual appearance and her decided air”

Meurent's importance

Interestingly, critics and scholars have been quick to downgrade Meurent’s role in the development of Manet’s work.

Adolphe Tabarant, writing in 1937, described how Meurant was “between 1862 and 1874, with long eclipses, because she was whimsical, Manet’s preferred model.” He went on to say that she was

"like a lot of girls of the lower classes who knew they were beautiful and unable to easily resign themselves to misery. She immediately consented to model”.

Writing again in 1947, Tabarant says,

“Victorine Meurent disappeared from circulation for several years and was silent about this disappearance that one knows was for romantic reasons […] A sentimental folly had taken her to America”.

Later in 1920, George Moore described the time he met Meurent, summarising her as: “A thin woman with red hair […] She had sat for Manet’s picture of Olympia, but that was many years ago. The face was thinner, but I recognised the red hair and the brown eyes, small eyes set closely, reminding me of little glasses of cognac”.

Unfortunately, what we know about Meurent has been distilled through decades of misogynist writing so that the dominant picture we have is of a sad, desolate lower-class model who “descended into alcoholism”, the “final disgrace” in the words of Tabarant.

In fact, Meurent was an artist of some note.

Meurent the Artist

Meurent’s work was admitted to the Salon. Tabarant described,

“What a surprise for Manet, that his neighbour in the same room was Victorine Meurent. She was there, smiling, happy, camped in front of her entry, which had brought her such honor, the Bourgeoise de Nuremberg au XVIe Siecle”.

Though Tabarant’s piece is thick with condescension, it offers a glimpse at the character of Meurent and her obvious accomplishments in painting.

Thankfully, art historians in the late 20th and 21st centuries have begun looking into Meurent’s story in more detail.

Eunice Lipton, writing in 1999, explored the life and work of Meurent in her book ‘Alias Olympia: A Woman's Search for Manet's Notorious Model and Her Own Desire’, recognising the influence of Meurent on Manet and their partnership as artist and model.