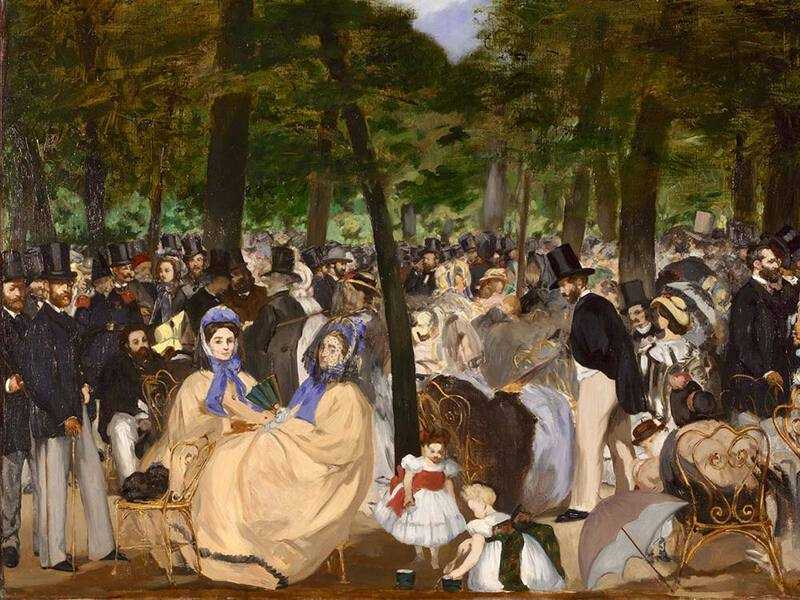

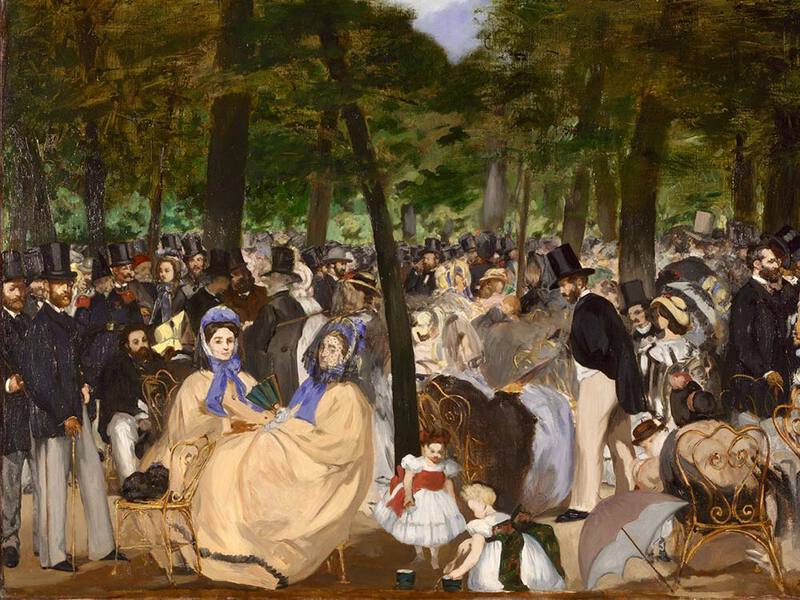

1. Music in the Tuileries (1862)

Manet’s painting ‘Music in the Tuileries’ from 1862 is seen by many as a declaration of the artist’s desire to paint modern life.

His radical style, showcased in this piece, is considered to be one of the earliest examples of modernist painting.

Around the time that he was working on the piece, Manet was corresponding frequently with poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire. In 1859, Baudelaire completed an essay titled ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, which was published in 1863. He said that he wanted to see art that displayed the “gait, glance, and gesture” of modernity.

Baudelaire's Influence

The influence of Manet and Baudelaire’s relationship can be seen in Manet’s painting, which focusses on a contemporary setting, fashion and activities. As journalist Antonin Proust recalled:

“[Manet] went almost every day to the Tuileries from two until four in the afternoon to make studies in the open air, beneath the trees, of the children playing and groups of nursemaids who had dropped into their chairs. Baudelaire was his constant companion.”

‘Music in the Tuileries’ is a statement of Manet’s desire to paint in an entirely new way. It is chaotic, dynamic and most importantly, it is modern. The figures do not appear to be posed or static, they are living, breathing people who inhabit urban Paris.

Interesting facts...

Manet painted himself at the far left of this picture. He also painted many of his friends, including his brother Eugene and Baudelaire.

The painting also featured in a court case. Collector bought the painting in 1903 and left it in his original will to London's National Gallery. But a codicil instead left the painting to the Dublin City Gallery. When doubts were raised about the codicil's validity, the two galleries agreed to split ownership!

Show me the music!

The irony of this piece is that despite its title, no music is seen being played.

There are no musicians, no instruments, and no obvious performances taking place. In this way, the piece contrasts with Manet’s earlier works that feature music and musicians such as ‘Spanish Guitarist’, ‘Street Singer’ and ‘Old Musician’, all from 1862.

What we do see are people socialising and engaging in conversation.

Hidden meanings?

This painting is the beginning of Manet’s preference of using titles to hint at the meaning behind the work, rather than describing what is actually taking place. Scholars have suggested that Manet’s painting was a commentary on the shifts in music and art taking place in France at this time.

Many of the figures depicted in the painting were passionate supporters of the new music style - headed by Richard Wagner - and this work alludes to the electric cultural debate happening around him, in the Tuileries and throughout Paris.

Where can I see it?

Music in the Tuileries is owned by London's National Gallery and Dublin's Lane Gallery. It splits its time between the two galleries!

2. Déjeuner sur l'Herbe (1863)

Painted in 1863, ‘Déjeuner sur l’Herbe’ is the piece that established Manet as the most controversial painter of his time.

At first glance, ‘Déjeuner sur l’Herbe’ is a clear example of realism, the movement that tried to produce realistic (and not idealised) depictions of scenes championed by Gustave Courbet.

However, on closer inspection the realism in the work melts away.

The foliage is hazy and formless, the setting looks as though it could be a stage background. There is something wrong with the perspective (the woman in the background is far too large).

Similarly, the figures are posed in a manner that copies an etching by Rainmondi, after Raphael’s ‘The Judgement of Paris’, suggesting that the painting was conceived and created in the studio.

Deeper meaning

Rather than simply being a realist piece, seeking to depict the real world, this painting has a deeper was intended to be a challenge by Manet to conventional art and cultural expectations.

In fact, Manet joked sarcastically about nude painting, saying “It seems I must do a nude”, a genre which he described as “the first and last word in art.”

When he announced his plans, he noted:

“They will attack me; let them.”

Hostile reception

Manet was well aware of the response his painting would receive.

He defiantly questioned the artistic conventions of the time that claimed nude figures were removed from reality and had (in the words of one critic)

“no more sex than mathematics”.

This hypocrisy of 19th century art went unchallenged, with sensual and realistic nudes gracing the walls of every gallery, whilst claiming to be detached and desexualized.

Manet’s painting confronts this unquestioned tenet of European art.

The nude female figure in ‘Déjeuner sur l’Herbe’ looks out of the painting with a bold, independent gaze that challenges the viewer. She is entirely in control of her sexuality and unlike classical nudes, there are no fig leaves, cherubs or Corinthian columns to veil it.

Where is it now?

Déjeuner sur l’Herbe is now found in the permanent collection of the Musee d'Orsay.

Learn more on our Déjeuner sur l’Herbe page. Did you know that Manet referred to this painting as 'the foursome' to his friends?

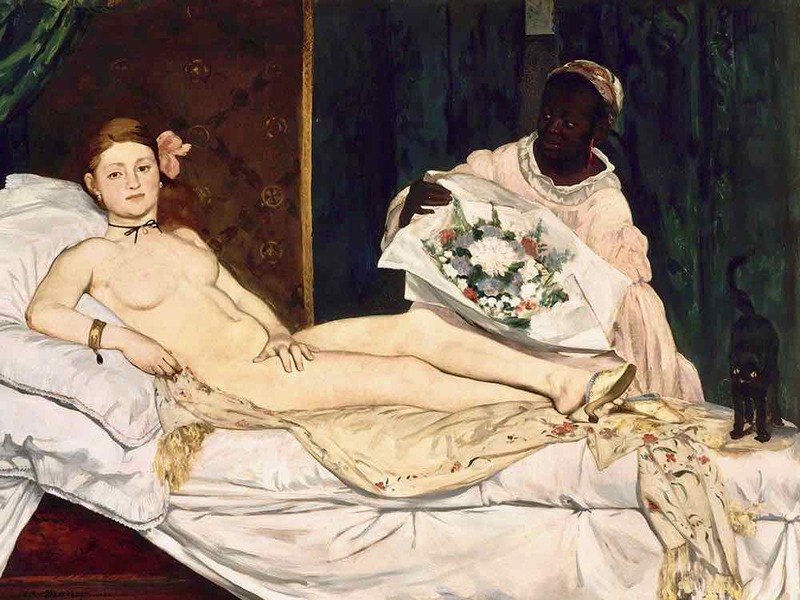

3. Olympia (1863-5)

Much like Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, Manet’s Olympia is a powerful statement that contradicts the firmly held conventions of 19th century art.

This painting of a female nude was scandalously modern to its contemporary viewers. This was particularly so because the painting has many pointers towards Olympia being a prostitute (read more on our Olympia page).

Acceptance by the Salon

At the time Olympia was painted, the key way that new painters could achieve recognition and sales was by displaying their works at the Salon des Beaux Arts in Paris.

But admission was controlled by a very conservative jury, who liked religious, allegorical or historical scenes.

Curiously, however, the jury accepted Olympia. It may be that they knew that the painting would provoke outrage and wanted to teach Manet a lesson.

Interesting fact...

The public responded to Manet’s painting with hostility, so much so that the painting had to be hung higher in the Paris Salon to prevent it being vandalised by viewers attacking it with their umbrellas and walking sticks.

Contemporary comments on Manet’s painting focussed entirely on its provocative depiction of a modern woman. It was clear that she was a prostitute and her brazen stare out of the canvas showed that she wasn't going to apologise for her way of making a living.

Even professional art critics could not get beyond their own sense of outrage.

Hostility

Journalists repeatedly described the woman as a corpse, including Victor de Jankovitz’s assertion that:

“The expression of [Olympia’s] face is that of a being prematurely aged and vicious; the body’s putrefying colour recalls the horror of the morgue.”

And Felix Deriege wrote:

“her face is stupid, her skin cadaverous […] she does not have a human form.”

In this reaction, it is possible to read just how unsettling depictions of modernity could be.

In the words of T.J. Clark “Olympia's sexual identity is not in doubt, it is how it belongs to her that is the problem.” ‘Olympia’ is one of Manet’s best paintings because it mocks classical painting traditions that had thus far gone unquestioned.

Inspiration

One reason why Olympia is so important is that it inspired Manet's fellow impressionists. It was Manet's was of saying: you can be different; the establishment, critics and public won't like it; but that is okay.

Another benefit was that Manet became quite famous.

Where is it now?

Olympia did not enter The Louvre until 1907. It moved to the Musee d'Orsay when it was opened in 1986, where it is still found.

Learn more on our Olympia page.

4. The Execution of Maximilian (1867-8)

Depicting the execution of Austrian archduke Maximilian, the Emperor of Mexico, Manet’s painting from 1867-68 was one of three works he painted to mark the event.

It is likely that he started working on the painting around the time that news of the execution reached Paris in July 1867. And Manet worked on a grand scale: the finished work measures 193 × 284 cm.

Rejected and banned ...

To create the work, Manet borrowed soldiers from a local barracks to act as models. He also attempted to recreate the faces of the victims from photographs. Despite his careful rendition, the painting was rejected from the Paris Salon and authorities banned the sale of the lithograph - because it was a thinly veiled criticism of French foreign policy.

In response to this intervention, Emile Zola began a public debate on state censorship.

One of the reasons for the controversy caused by Manet’s painting was his depiction of a contemporary subject, rendered on the scale of a history painting. ’The Execution of Maximillian’ bears a striking resemblance to Francisco Goya’s painting 'The Third of May 1808’.

Manet would have seen the painting at the Prado in Madrid in 1865 when he visited the city. The similarities especially lie in the decentered composition, the poses of the figures and the bleak, empty landscape setting.

Chopped into pieces

This painting was found in Manet’s studio when he died in 1883 but much of it had been damaged. This was due to a combination of poor storage conditions and intentional cutting, though it is not known by who or when.

The painting was further fragmented by Léon Leenhoff, Manet's son, leaving four separate parts of the canvas which were then sold individually.

Edgar Degas immediately recognised the importance of the painting when he saw one piece of the work and he eventually succeeded in bringing the fragments back together.

Where can I see it?

In the care of London's National Gallery, who bought the fragments in 1918, the sections were united on a single canvas in the late 1970s.

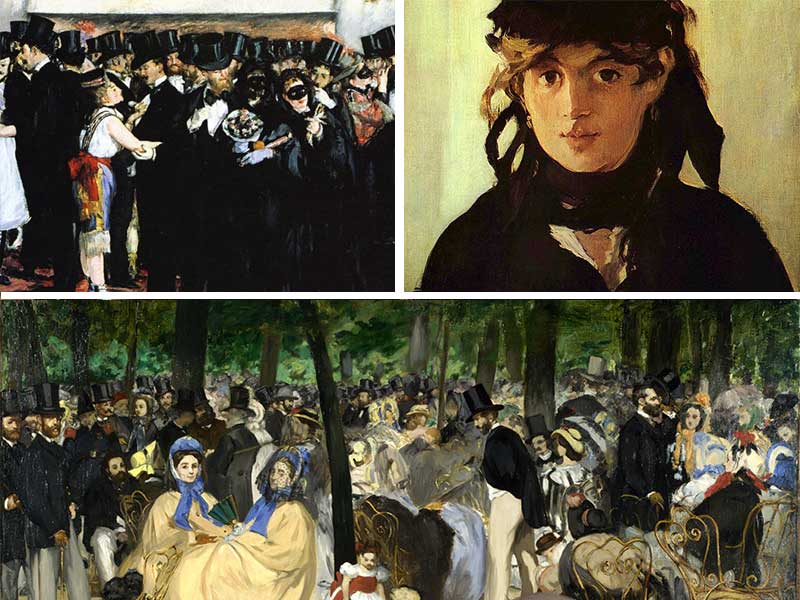

5. Masked Ball at the Opera (1873)

Unlike many of the other Impressionist artists, Manet was born into influence and wealth.

‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ (1873) is an elegant example of the fashionable circles the artist moved in.

The masked ball depicted in this painting was an annual event during Lent. Much like ‘Music in the Tuileries’, Manet made several sketches for this painting and completed the work in his studio. Many of the figures he depicted are his friends who posed for the piece, including writers, musicians and fellow artists.

The scene

The scene is busy and hints at more activity happening outside of the frame. Cropped legs and bodies lend the scene a sense of immediacy that contrasts heavily with the carefully positioned and contained style of academic paintings.

Can you spot the dangling legs of an acrobat?

Criticising high society ...

The mass of bodies is also suggestive of the nature of the event, known for its sexual undertones.

The suggestiveness of the painting may be one of the reasons that it was rejected from the Paris Salon of 1874. In the words of Julius Meier-Graefe, writing in 1912,

“The scarcely-concealed lust of the gestures of the soliciting men, the women offering themselves […] the calculating glances, groping hands, brutal winks, all the typical gestures of the proceedings, metropolitan in every nuance”.

The ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ revealed the habits of the elite in modern Paris.

Where can I see it?

Masked Ball at the Opera is now found in Washington DC's National Gallery of Art.

Learn more on our Masked Ball at the Opera page.

6. Berthe Morisot Reclining (1873)

This portrait from 1873 is a captivating example of Manet’s ability to capture likenesses, despite using his customary truncated and flattened painting style.

A mistake?

It is thought that this work may have originally been part of a much larger canvas, as Etienne Moreau-Nelaton describes:

“when the work was finished, a gross mistake teased its author so much that instead of correcting a hand that was too large for his liking, he slashed his work in a movement of humour and kept the face […] the rest seeing themselves mercilessly sacrificed”.

What resulted from this brutal editing process was a completed piece that is distinctly modern in style, thanks to its cropped focus.

Monet's use of Black

As was his preference, Manet depicted Morisot’s eyes as black instead of green, darkening her features and accentuating the contrast with the whiteness of her cheeks and neckline.

Scholars have cited the similarity of the style to works by Goya, possibly drawing inspiration from Morisot’s Spanish heritage.

Here are some other examples of Manet's use of black:

A gift

Manet presented the work to Morisot and it stayed in her private collection for her whole life. It is the only portrait by Manet that she owned and she describes it in her notebooks as a

“bust portrait cut from a full-length portrait lying on a sofa”.

Interesting fact...

Manet had a very close friendship with Berthe Morisot. Indeed, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that they had an affair. Morisot ended up marrying Manet's brother, Eugene.

Where is it now?

These days Berthe Morisot Reclining is found in Paris' Musee Marmottan Monet, a brilliant (and fairly quiet) museum which tends to get overlooked in favour of the D'Orsay, Orangerie and Louvre.

7. The Railway (1874)

Accepted to the Paris Salon of 1874, ‘The Railway’ was critiqued for its unfinished appearance.

The other major area of dissatisfaction was the painting’s title: the railway mentioned is not visible in the work, just a cloud of smoke from a steam engine and fragments of a railway station.

New technology ...

Manet chose to set his painting at the Gare Saint-Lazare, the biggest and busiest train station in Paris. This station was a symbol of modern, industrial technology and the new form of travel that had changed life in France.

Yet it is barely to be seen.

... disappears in a puff of smoke

Instead, the work features a woman and a child, sitting against black iron railings. The two figures are in opposition to one another; the girl wears a white dress with her hair tied in a ribbon whilst the woman is clad in black with hair flowing down her shoulders.

The painting is confined to a narrow view, a snapshot of one life in this busy, modern setting. Manet does not focus on the prowess of the machinery or the spectacle of the station, he centres on the figures who inhabit the space.

In doing so, Manet created a highly intimate portrait of modernity. The painting is detached, immediate and ambiguous. The two figures are separated from one another by their positioning, the woman’s expression is unreadable. It has been suggested that the woman in the painting is a prostitute (as in Olympia), while the status of the young girl is unknown.

But they are well-dressed. The woman has a small dog, a fashionable accessory at the time, and is reading. Perhaps they are waiting for a relative to return? Or going on a journey.

Claude Monet was to use Gare Saint-Lazare as the setting for his eponymous series of paintings, produced three years later. Here's one of the 12 canvasses Monet produced of the station.

Where is it now?

Manet's The Railway is now found in Washington DC's National Gallery of Art.

8. Nana (1877)

Once again, Manet chose the modern prostitute as the subject for his 1877 painting titled ‘Nana’.

Inspired by Emile Zola’s novel ‘L’Assommoir’, the figure of Nana is drawn as a “grand cocotte” or “glittering courtesan”, fashionably dressed and assuming the mannerisms of the upper and middles classes.

The sexuality of the subject is overt, with the figure clad in a corset, looking out towards the viewer with a slight smile on her lips. A partially cropped figure to her right, who stares at her whilst she stares at the viewer, reveals himself to be her client.

A huge painting

This work was painted on an enormous scale, measuring 154 x 115 centimetres, and the figure of Nana is almost life size. Manet painted directly onto the canvas, without layering the oils or using a topcoat. The thick lines and dark blocks of colour form an expressive Impressionist piece.

Despite the originality of the work, the painting was refused from the 1877 Salon. This is likely to have been due to the inference of Nana’s profession and the social anxiety surrounding the concept of so-called ‘hidden prostitutes’ at this time.

Where is it now?

Nana is now found in the Kunsthalle Hamburg museum in Germany.

9. Le Printemps (Spring) (1882)

When Le Printemps was exhibited at the Salon of 1882, Maurice de Seigneur described the reception:

“Manet’s defenders are delirious, his detractors stupefied”.

Painted in profile, echoing early Renaissance portraits of gentile women, Springtime sees Manet depict his model in floral prints and surrounded by blossoms.

The Four Seasons

The painting was first inspired by Antonin Proust, who proposed the idea of commissioning a series of paintings based on the four seasons. They considered personifying each of the seasons as a fashionable and beautiful contemporary woman.

This modern theme, which drew on classical traditions of mythological painting, appealed to Manet. He understood what popular appeal such a series could have and it aligned with his desire to paint modern life.

Like depictions of the seasons in Greek and Roman art and later in Renaissance paintings, Manet was inspired to create a symbolic cycle of paintings, starting with Spring.

Parisian Poise

Manet wished to capture the fashion and poise of Parisian ladies, painting on to canvas the figures who could be seen at any time in the Jardin du Luxembourg and the Tuileries.

He chose the beautiful Jeanne Demarsy as his model. As Proust recalled:

“Manet spent a day in ecstasy contemplating some material that Mme Derot was unrolling. The next day, it was the hats of a well-known milliner, Mme Virot, which filled him with enthusiasm. He wanted to design a costume for Jeanne, who subsequently took on the stage name Mlle. Demarsy”

An unfinished series

Sadly, Manet did not have time to complete the series. He came close to finishing ‘L’Automne’ shortly before his death in 1883, but as Edmond Bazire described in 1884,

“Time failed him […] ‘Winter’ and ‘Summer’ were never painted, and it is a loss and a regret the more”.

Where can I see it?

Spring was bought by the J Paul Getty Museum, California, in 2014 for a whopping $65 million. It holds the world record for the most expensive painting by Manet.

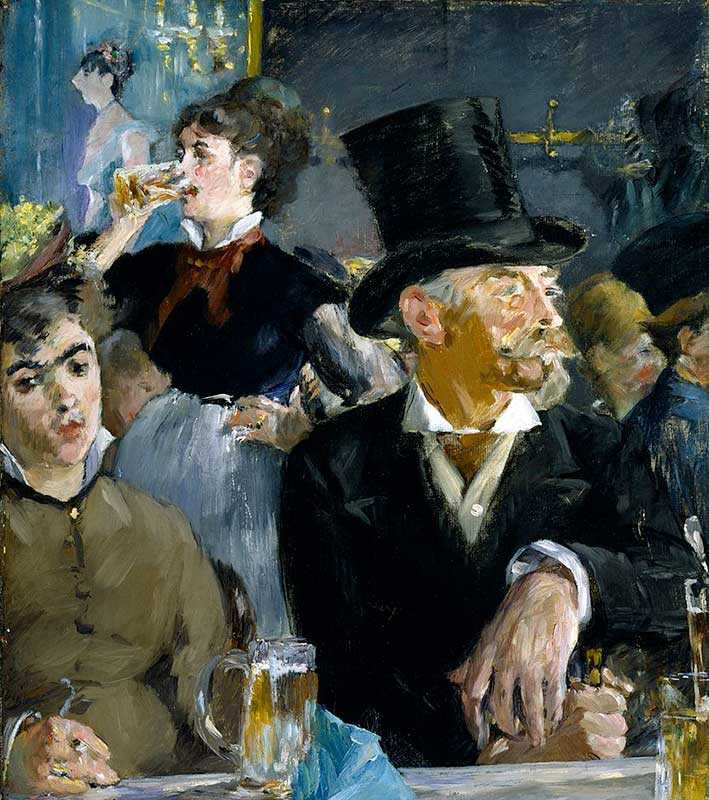

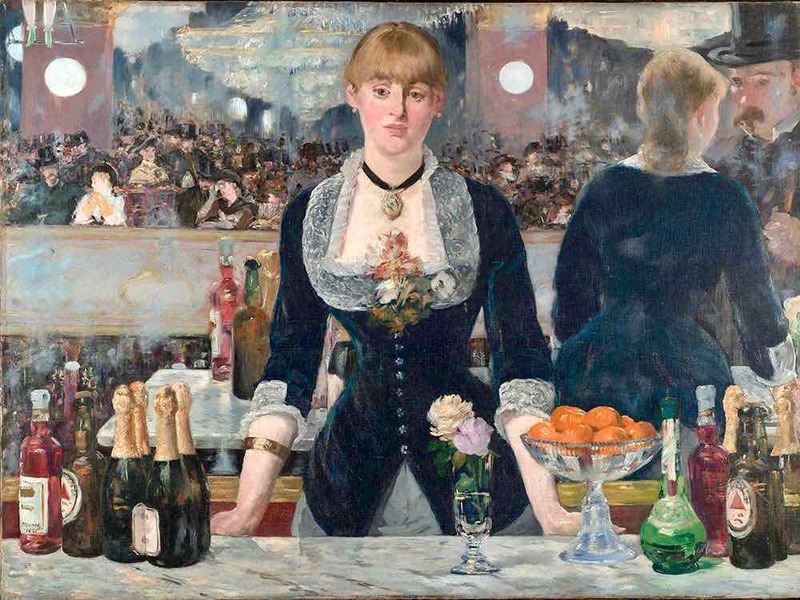

10. Bar at the Folies Bergeres (1882)

Exhibited at the 1882 Salon next to Le Printemps, ‘Bar at the Folies Bergere’ was one of Manet’s final masterpieces.

He died the following year.

Defying Physics

This painting stirred a great deal of debate when it was first revealed and continues to be a subject of scrutiny for art historians. From the ambiguity of the woman’s expression to the inaccuracy of the reflection in the glass behind her, there have been countless theories as to what Manet’s intentions were when he painted this work.

What is known is that the painting was a result of careful, painstaking preparation. Numerous studies were made before he began the final piece. Similarly, Manet made several changes to the painting once he had started painting.

X-ray analysis has revealed that the barmaid was first painted with crossed arms, indicating a more defensive pose, for instance.

Who is the Barmaid talking to?

This painting is perhaps one of Manet’s most famous because of its subtlety and perplexing composition. Who is the Barmaid talking to? Her father? A lover? A client?

That was one of Manet's final paintings and also one of his most popular - giving the piece an almost poetic significance.

From the start of his career to the end, Manet sought to portray modern life in a real and yet nuanced way, leaving much unsaid in his artworks. In this last masterpiece, he once again opened the interpretation up to the viewer, leaving behind hints and clues to be deciphered.

Where can I see it?

Bar at the Folies Bergere is one of the finest paintings at London's Courtauld Gallery. It is also one of our Top 10 Impressionist Paintings.

11. What's Next?

Want to learn more about Manet and the Impressionists?

We suggest that you check out our Edouard Manet Biography page. Did you know that Manet attended the Rio Carnival, saw armed conflict and fought a duel?

Once you have read that, why not check out our timeline and quiz pages, or learn more about the most famous impressionist of all time, Claude Monet?

Further reading

To take your knowledge to the next level, check out our resources page - you'll find recommendations for the best impressionist books, videos and gifts.