1. Sunflowers (van Gogh)

Van Gogh's Sunflowers are not just vibrant depictions of floral arrangements.

They represent a profound shift in artistic approach, marked by subjective interpretation, emotional intensity, and bold experimentation with colour and form.

Vital statistics

Van Gogh painted four versions of his Sunflowers in Arles in 1888. They are shown in the order in which they are painted above. Van Gogh's composition gets more complex as time goes by: the first version has three sunflower heads and the last has 15.

In January 1889, van Gogh made a copy of the third version of the Sunflowers, and two copies of the fourth.

Six of the seven paintings survive. Sadly, the second version (with a dark blue background) was destroyed in an allied air raid over Japan in August 1945.

Of the remaining six, five are on public display around the world, found at:

- The Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Germany (third 1888 version)

- The National Gallery, London (fourth 1888 version)

- The Philadelphia Museum of Art (1889 copy of third version)

- The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (1889 copy of fourth version)

- The Sompo Japan Museum of Art, Tokyo (1889 copy of fourth version)

Use of colour

Van Gogh's use of colour is perhaps the most striking aspect of his Sunflowers.

Rather than adhering to naturalistic colour schemes, he employs vivid, almost unnatural hues of green, yellow and orange to convey a sense of heightened emotion and intensity.

Van Gogh's bold and expressive brushwork further enhances this sense of movement and emotion, as seen in the swirling patterns, wide outlines and thick impasto layers that characterise his style.

Beyond impressionism

One of the defining characteristics of post-impressionism is the departure from the purely observational nature of impressionism. While impressionists sought to capture the fleeting impressions of light and atmosphere, post-impressionists like van Gogh aimed to convey their own emotional responses and inner visions through their art.

Key post-impressionistic aspects of van Gogh's Sunflowers are:

- The flattened background to the compositions, which focus the viewer's gaze on the Sunflowers themselves.

- The mix of sunflowers van Gogh chose for his third and fourth compositions: some in bloom, others turning to seed ready to be sewn to create the next generation. In these ways, the composition might be said to be about the circle of life.

- The exaggerated size of the seed heads shown in the fourth version, especially by comparison with the vase in which they are held.

- The unusual colours shown in one of the 1889 copies - including light blue highlight (see below).

These tricks are used to create a sense of immediacy and intimacy, drawing the viewer into the scene and inviting them to experience the artist's emotional journey.

Why did van Gogh paint the Sunflowers

There are three reasons.

First, van Gogh loved the colour yellow, explaining to his brother Theo that

"yellow stands for the sun!"

Second, he was Dutch - so flowers were very much burned into his subconscious.

But third, and more immediately, van Gogh wanted to decorate a room in his famous 'Yellow House' in Arles ready for the arrival of Paul Gauguin.

Van Gogh hung two 1888 versions of Sunflowers in Gauguin's room (the Munich and London versions). The men didn't live together long. In December 1888, they had the furious argument that led to van Gogh cutting off a portion of his left ear.

Van Gogh painted the three copies of the Sunflowers in Arles in the months following the argument, probably as a form of personal therapy.

Sadly, van Gogh could not recover on his own. He was admitted to the Saint Remy asylum in May 1889, where he stayed for a year. But van Gogh had not recovered and he committed suicide in Auvers in July 1890. Fittingly, Sunflowers were placed on top of van Gogh's coffin, which was surrounded by his most treasured paintings - amongst them his Sunflowers.

Read more on our Van Gogh Biography and Van Gogh Timeline pages.

2. Vision After the Sermon (Gauguin)

Painted in 1888, when Paul Gauguin was living in Brittany, Vision After the Sermon represents his first serious attempt at abstraction.

Paul Gauguin had already dabbled at copying the impressionists. But he wanted to take his art further. As he explained in a letter:

“Art is an abstraction; as you dream amid nature, extrapolate art from it and concentrate on what you will create as a result."

Key Features

Vision After the Sermon is a striking - and unusual - piece of work. Here are some key features.

First, note the Breton women in the foreground who - we are told by the painting's title - have just heard a religious sermon. All but one of the women have their eyes closed.

Second, a diagonal tree cutting off the Breton women from the main action in the top right hand corner of the painting. Curiously a cow seems to be tethered to the three (see the top left).

Third, Jacob fighting with a mysterious yellow-winged angel (which seems to have him in a head-lock!). This is a reference to this scene at Genesis (32:22-32), during which Jacob wrestles an angel through the night - at the end of which he is given a new name, Israel. Here's the biblical text:

That night Jacob got up and took his two wives, his two female servants and his eleven sons and crossed the ford of the Jabbok. After he had sent them across the stream, he sent over all his possessions. So Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him till daybreak. When the man saw that he could not overpower him, he touched the socket of Jacob’s hip so that his hip was wrenched as he wrestled with the man. Then the man said, “Let me go, for it is daybreak.”

But Jacob replied, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.”

The man asked him, “What is your name?”

“Jacob,” he answered.

Then the man said, “Your name will no longer be Jacob, but Israel, because you have struggled with God and with humans and have overcome.”

Fourth, swathes of the colour vermillion (orangy-red) are used in the top half of the painting. Note that Gauguin does not try to create a detailed background. He instead draws his inspiration from the two-dimensional Japanese woodcuts that he collected.

Interesting fact...

Gauguin tried to give this painting to two churches; but they both refused to accept it.

Gauguin's take ...

Somewhat enigmatically, Gauguin described the scene as follows when he wrote to van Gogh:

"For me the landscape and the fight only exist in the imagination of the people praying after the sermon."

Vision After the Sermon is now found in Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh.

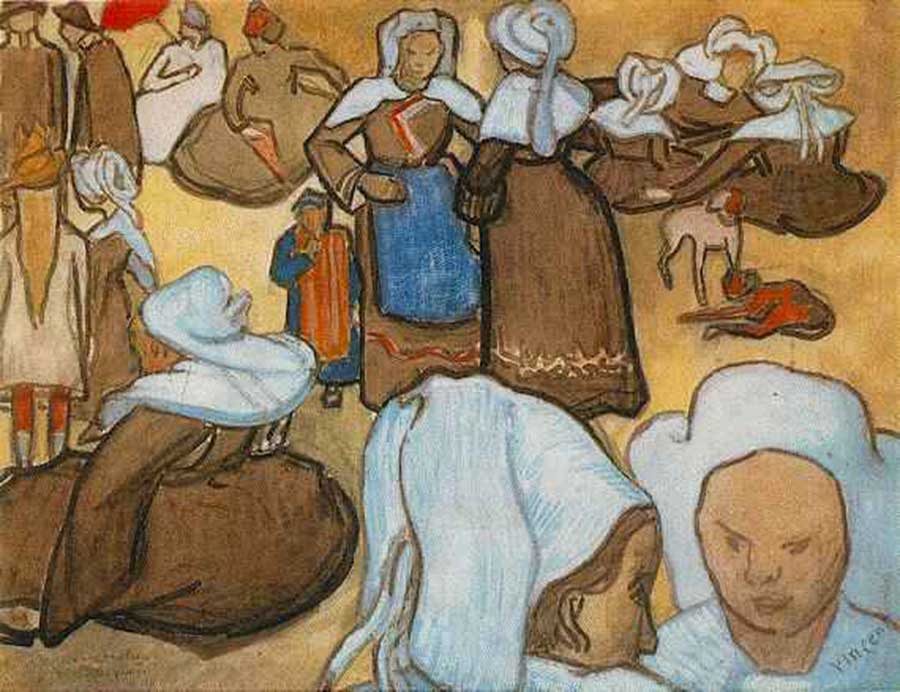

3. Breton Women in Green Pasture (Bernard)

Emile Bernard (1868-1941), twenty years Gauguin's junior, worked together with Gauguin in Brittany in 1888 to invent an artistic style known as synthetism.

The style emphasised simplicity and usually involved bright colours, a flat plane, and thick, dark outlines around shapes. Breton Women in Green Pasture (1888) is a good example:

The painting

The depiction of 15 figures and two dogs at first looks like it is a series of studies made for a more orthodox composition. But there is something magnetic about this work. notice in particular:

- The almost radioactive green background, combined with splashes of bright red and orange.

- The flat plane, meaning that the large heads of the two women at the bottom right of the composition almost merge into the two central figures.

- The thick black outlines, particularly noticeable on the white bonnets worn by the Breton women.

Van Gogh's copy

When Gauguin went to Arles to live with van Gogh at the end of 1888 he carried with him a copy of Breton Women in Green Pasture. Van Gogh went on to produce a copy in watercolour, a copy of which is found below (see Vincent's signature in the bottom right hand corner).

Bernard

Remarkably, Bernard painted this composition when he was only 20 years old. He had already been kicked out of the conservative Academie des Beaux Arts for

"showing expressive tendencies in his paintings".

Indeed, Bernard's most productive period ended in 1897, when he was 29 years old. He went on to write plays, poetry and art history

4. Night Cafe in Arles (van Gogh & Gauguin)

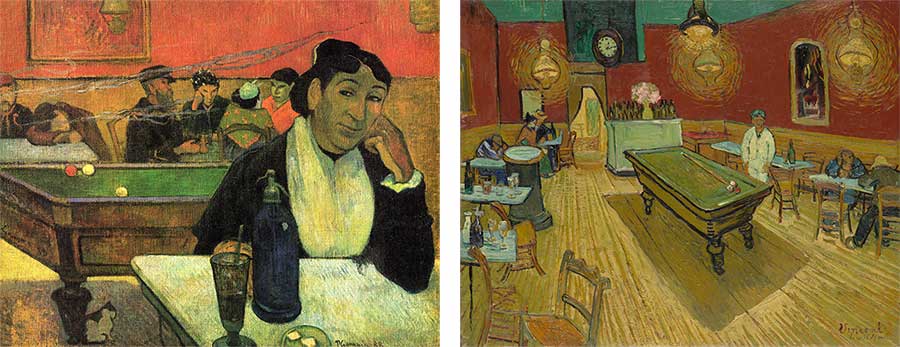

Van Gogh and Gauguin spent 63 days together in Arles in late 1888. The two men shared artistic ideas, challenged each other and occasionally painted the same motif.

The Night Cafe in Arles is the most famous example of this. Here are the two men's works (Gauguin on the left, van Gogh on the right).

The scenes

At first blush the scenes are very different. Gauguin focuses on a lady, with drinkers in the background. Van Gogh, on the other hand, has no central figure and instead directs the focus towards the electric lights and pool table.

On the other hand, there is an air of desperation and despondency in both scenes.

- The central figure in Gauguin's work is almost certainly a prostitute (the Café de l’Alcazar was a well-known pick-up joint), and the top left of van Gogh's work may also show a man picking up a street worker.

- Both paintings show drinkers who are passed out on the cafe's tables.

- Both paintings make heavy use of red and green, creating a scene that feels unhealthy - a point emphasised by the smoke wafting across Gauguin's canvas.

Symbolism

None of this was an accident. As van Gogh explained in a letter to Theo, he wanted to

“express the idea that the café is a place where one can ruin oneself, run mad or commit a crime. I have tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green”

So these works were not about recreating a motif with photographic precision. it was about making a statement and making the viewer feel something.

5. Starry Night (van Gogh)

Van Gogh painted arguably his most iconic work, Starry Night, in June 1889. Remarkably, he painted it from his room at the Saint-Remy asylum.

The scene

The viewer's eye is immediately drawn to the warm and bright yellow of the moon. Most people then tend to notice the over-sized star (which probably include Venus, which was visible from Provence in June 1889). This is one of 11 stars in the composition.

The next most noticeable feature is the swirling of the sky. The scene was probably painted close to daybreak, as shown by the band of lighter paint immediately above the hills.

The most interesting aspect of the sky is found in the upper middle part of the painting - if you look carefully, you will make out a wave breaking onto a beach, perhaps an oblique reference to van Gogh's troubled mental state.

The lower third of the painting depicts Saint Remy, even though this could not be seen from the asylum (van Gogh had sketched it previously). And structure is added by a large cypress tree, seemingly swaying in the early morning wind.

Reaction

Van Gogh did not think much of this masterpiece. He didn't even think it was worth the postage charge to send it back to his brother Leo, to see if he could sell it in Paris

Interpretation

Many people just marvel at van Gogh's brushwork. But if you want to interpret Starry Night, here are three ideas:

(1) Mental troubles. Van Gogh's troubled mental state is well known. Some people look at the swirling of the sky and compare it with van Gogh's swirling mind.

(2) Life and death. Cypress trees were associated with death in 19th century France, often being found in cemeteries. And van Gogh sometimes compared death with going to a star, writing as follows:

Just as we take the train to go to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to go to a star.

(3) The bible. A third theory is that Starry Night is a nod to Genesis, which says in Chapter 37 as follows:

" ... I have dreamed a dream more; and behold the sun and the moon and the eleven stars made obeisance to me."

These are interesting debates, to which we'll likely never have a conclusive answer.

6. The Can Can (Seurat)

Georges Seurat (1859-1891) was the pioneer of the Pointellist movement, which used the impressionist bright colours but also scientific colour theory.

We have chosen The Can-Can (Le Chahut) for our list. Painted in 1889, two years before Seurat's untimely death at the age of 31, the work is carefully composed, uses a sophisticated colour palette, and depicts a risque scene.

The composition

The viewer's eye is first drawn to the dancing line, dominated by the first female dancer. She raises her leg high, holds her skirt with her right hand, and is sprouting a tail. Perhaps surprisingly to the modern eye, the dancing line comprises two men and two women.

The double-bassist, with his back turned, is the next most important figure. Notice the shimmering of his suit jacket, which on close inspection can be seen to be filled with dots of blue, red and green.

The cheerful conductor is the next figure to investigate. Sporting an impressive moustache, he seems to be watching the dancing line rather than his musicians.

Finally, a somewhat sinister spectator is found in the bottom right of hte painting. Seemingly looking up the female dancer's dress, he also appears to be wearing lipstick.

Inspiration and technique

Seurat attended the fourth impressionist exhibition in 1879 and adopted the impressionists' use of modern scenes. But there were two critical differences:

- Whereas the impressionists often painted their works quickly, working outside, Seurat's scenes were far more considered. Note the structure he gives to the Can Can by the vertical line on the left hand side, intersected by the neck of the double bass.

- Seurat did not paint using the broad brush strokes favoured by the impressionists, but instead by building his composition using thousands of tiny dots. There was a scientific basis for his approach: colour theory says that colours appear brighter if contrasting dots of paint are placed next to eachother.

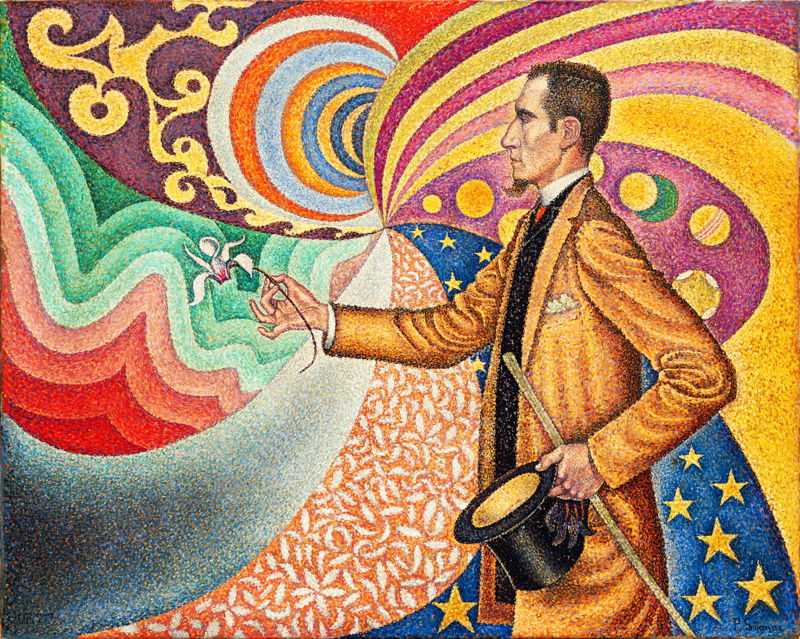

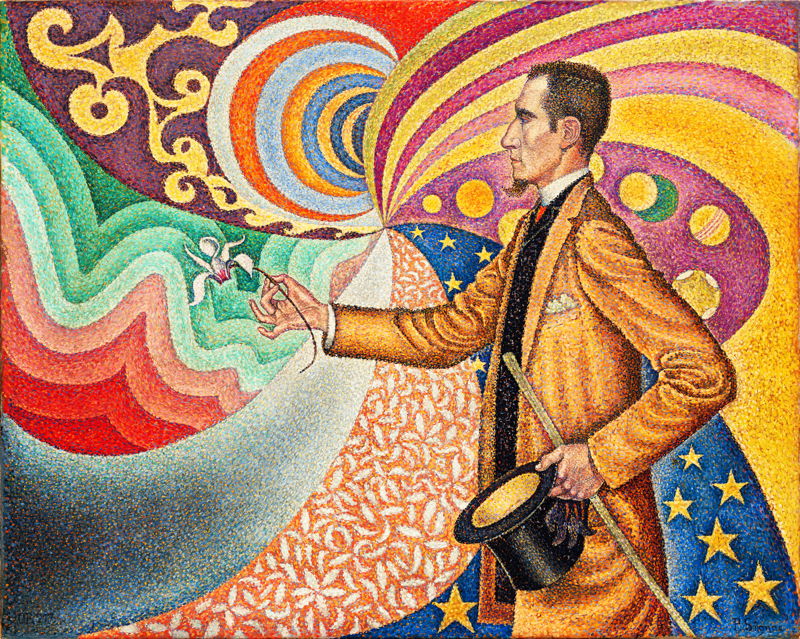

7. Felix Feneon (Signac)

Paul Signac worked alongside George Seurat to give the world pointillism.

This striking work shows art critic Felix Feneon as a magician, pulling a lily out of his hat. It is almost as if he is unveiling the colour theory trick that had been worked out by the pointillists.

The painting

Closer inspection reveals a number of important points:

- Feneon is painted sympathetically: he is wearing a striking yellow jacket, sporting a distinctive goatee, and is generally depicted as a man in total control of his world. This is not surprising given that Feneon was the first art critic to champion the pointillists.

- The arrangement of the orchid's petals is reflected in the arrangement of Feneon's fingers and indeed in the swirling background to the composition.

- The patterns are all completely different and hard to categorise (though note the planets behind Feneon's torso). This was no doubt deliberate, perhaps reflecting Signac's anarchistic tendencies.

Interesting fact...

The work was not a hit within the artistic community. Camille Pissarro, for example, described it as "bizarre" and lacking both decorative and emotional appeal.

The work is now found in New York's MoMA.

Signac

Unlike Seurat, Signac lived a long life - he died in 1935 at the age of 71. He is best remembered for his pointillist works, which are important in their own right and also because they inspired the Fauvist artists like Henri Matisse.

Signac's output decreased after the First World War, but he continued to paint, experimented with other media, sponsored promising artists, and wrote widely on subjects including art, anarchism and anti-fascism.

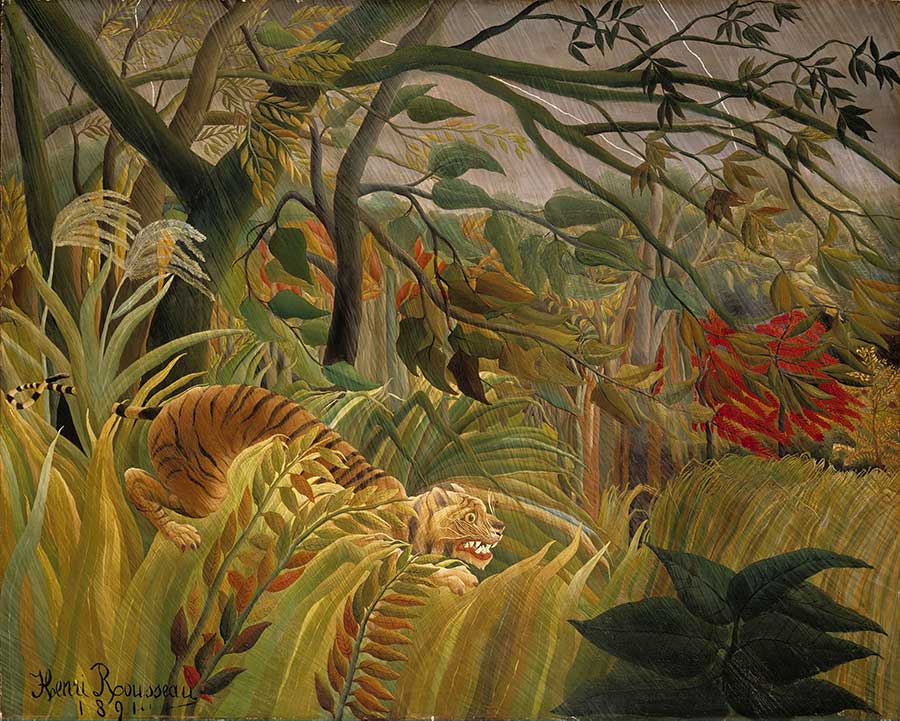

8. Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Rousseau)

Tiger in a Tropical Storm, or 'Surprised!', is the first of Rousseau's jungle paintings, the works for which he is best known.

The scene

Rousseau depicts a crouching tiger in the middle of a storm. The animal's eyes are wide and wired, and the second title of the painting - Surprised! - suggests that the tiger is either surprised that the storm has arrived or is going to surprise someone or something.

Rousseau removed any doubt many years after producing the painting by explaining that the tiger was about to attack a group of hunters.

Other notable features of the painting are:

- Shades of green. Rousseau built up the painting gradually over time using what seem to be scores of different shades of green.

- Clean edges. If you examine almost any aspect of this work, you will see sharp edges, which helps to make the painting realistic and enhances the brightness of the colours.

- Size. This is a huge painting, measuring 132 x 160 cms.

Reaction

Rousseau submitted Surprised! to the French Academy of Painting and Sculpture, but it was (like the works of many impressionists decades before) rejected. And so he first showed it at the Salon des Independants in 1891 (an annual exhibition organised by, amongst others, Seurat and Signac).

The critical reaction was mixed. Many mocked the naivety of Rousseau's work, also commenting on the apparent absence of perspective - producing a very 'flat' effect.

But others got it. Félix Vallotton said this:

‘His tiger … ought not to be missed: it is the alpha and omega of painting …. As a matter of fact, not everyone laughs, and some who do are quickly brought up short. There is always something beautiful about seeing a faith, any faith, so pitilessly expressed.'

Rousseau's life

Rousseau lived from 1866 to 1910, and was a customs officer by profession - earning him the nickname 'Douanier'. He took up painting late in life and produced Surprised! at the age of 35.

Rousseau's lack of formal training may have led to a flat work that has some problems with composition - the tiger seems to be floating. But the result is stunning. Not bad for a man who had never been to a jungle or seen a real-life tiger, working from prints and visits to botanical gardens.

Rousseau worked on his art full-time from the age of 49, and went on to produce 20 jungle works, including in 1905 The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope. His clear, striking and colourful works were an inspiration for the next generation of painters, including Pablo Picasso (who hosted a banquet in Rousseau's honour in 1908).

Surprised! is now found in London's National Gallery.

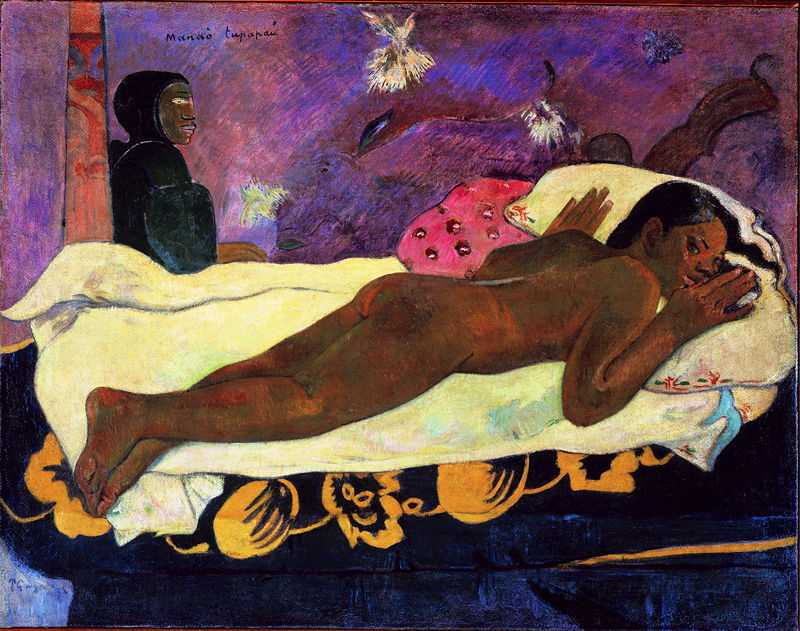

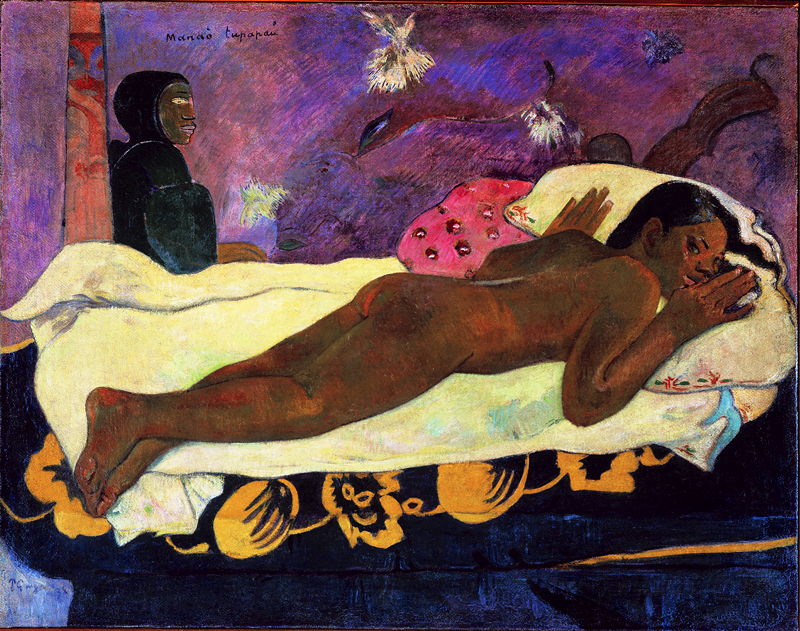

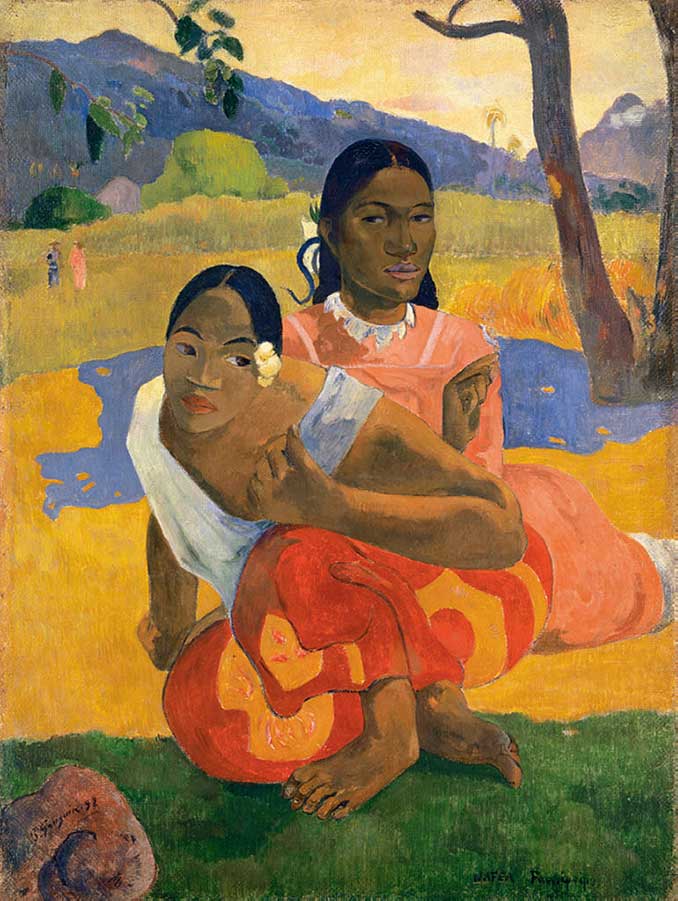

9. Spirit of the Dead Watching (Gauguin)

Paul Gauguin was a narcissistic cad. But he also produced breathtakingly innovative - not to mention shocking - paintings.

The painting

Gauguin's painting centres around a naked girl lying startled on her bed. The model was Gauguin's 13 year-old 'wife', who he 'married' after leaving his family in Europe and setting sail for Tahiti in 1891.

Interesting fact...

The model - Teha'amana - featured in a number of Gauguin's paintings. And she was not the only 'wife' Gauguin took in Tahiti. In total, he married three brides in the far east, and sadly gave them all syphilis.

The pose is obviously indecent and the model is scared, probably as a result of the female spirit standing behind her (though it is possible, perhaps likely, that she was also scared of Gauguin).

But leaving aside the baggage that comes with any Gauguin work from this period, the painting also pushed artistic boundaries. It is not a depiction of real life, but of ideas from Gauguin's mind - signalling the start of the symbolist movement.

Gauguin in French Polynesia

Gauguin led a highly unconventional and controversial life. He worked as a successful stockbroker until the early 1880s, when he quit to focus on his painting (a hobby until them). He painted in impressionist style for a while, and then moved towards symbolism when he worked with (first) Emile Bernard in Brittany and (later) Vincent van Gogh in Arles.

But Gauguin couldn't find peace. After an unsuccessful trip to Panama in 1887, he sold as many paintings as he could and set sail for Tahiti in 1891 (leaving behind his estranged wife and five children). He said that he was looking for a more "savage and primitive" existence. But, as we have said, he does not treat the locals well.

On the other hand, his symbolist and primitivist art is striking and eventually becomes remarkably popular. Here's another well-known Gauguin painting from this period, When Will You Marry (1892):

Things did not, however, end well for Gauguin. After a brief return to France in 1893, he ended up in Marquesas where he got into a big fight with the local administrators, resulting in a jail sentence. But before being taken away he died of syphilis in May 1903 at the age of 54.

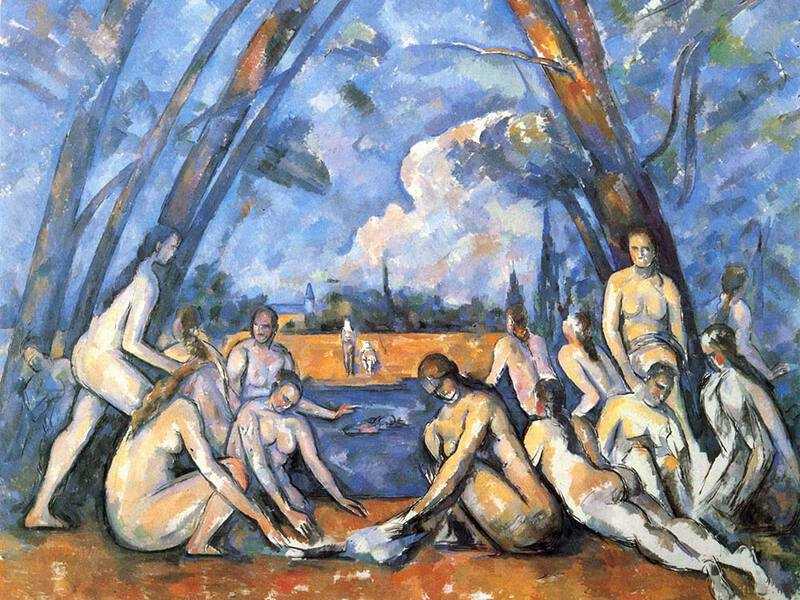

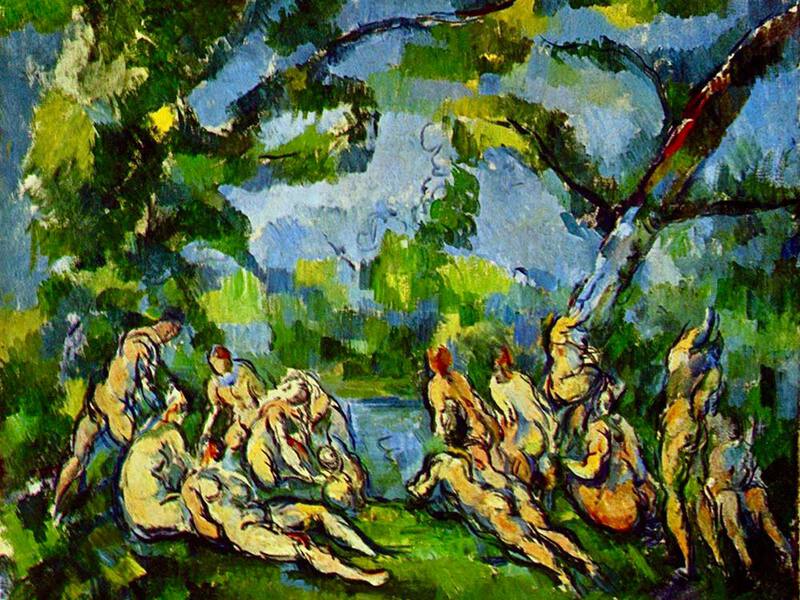

10. The Large Bathers (Cezanne)

Cezanne spent much of the last decade of his life working on three huge canvasses called Les Grandes Baigneuses (or The Large Bathers).

Here is the most well-known version:

The Bathers are naked on the banks of a river, their facial features only sketched. A town can be seen in the. background and structure is added by trees leaning to form a pyramid at the top-centre of the canvass.

One main colour

The predominant colour in this version of The Bathers (found in the Philadelphia Museum of Art) is blue, and the same is true of the smaller version held in London's National Gallery. But the third version, found at the Art Institute of Chicago, is predominantly green.

Geometry

Perhaps more important is Cezanne's use of geomereical shapes to give structure to his work. Cezanne had been developing this technique from his impressionist days, but the use of colour bocks, and triangular and other shapes, was a huge influence on the cubists like Pablo Picasso who followed.

Note, in particular, how Cezanne uses human bodies as part of his structure.