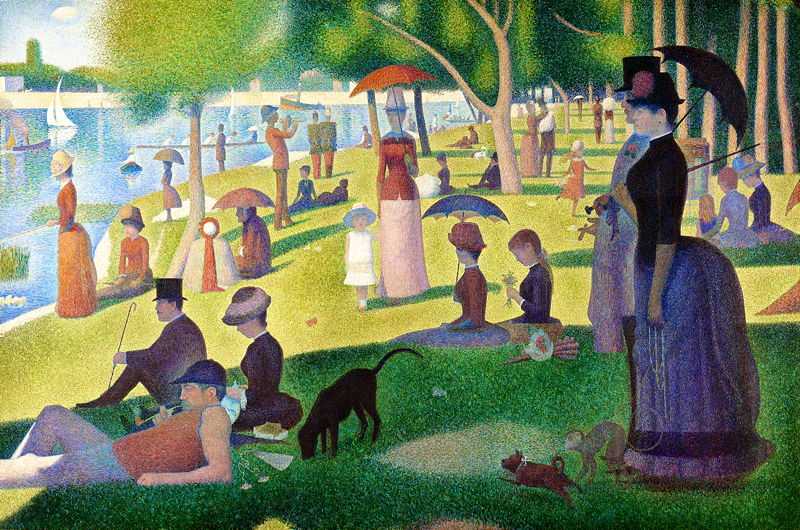

1. Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884)

Arguably the most celebrated artwork by Seurat is the enormous ‘La Grande Jatte’.

When it first entered the scene at the final impressionist exhibition, in 1886, it was considered revolutionary and has only become more prevalent in subsequent decades.

Today, the 3 x 2 metre canvas stands as a definitive example of late nineteenth-century art. This painting is now so famous that it has even been parodied by popular culture. It is therefore fair to say that ‘La Grande Jatte’ is Seurat’s finest masterpiece.

The image itself displays Parisian locals spending a sunny midday on the banks of the Seine. People and pets congregate, contemplate and recline in what seems to be a peaceful piece.

Interesting fact...

But upon closer inspection, there are a few peculiar points of interest. In the foreground are a fashionable couple, shrouded in shade, and on a leash is their pet monkey. Furthermore, in the far background, some men in uniform stroll away, their silhouettes blocky, making them look like toy soldiers.

Over the course of his career, Seurat gained a reputation as a artist obsessed with detail. Before undertaking the mammoth task of painting this piece, Seurat ensured that every single element was scrupulously perfected. He spent 2 years preparing, including making 28 sketches, 28 oil experiments and 3 canvases for practice.

The final piece was constructed in his workroom, giving him full control of the scene. This editing of the landscape completely opposed the ethos of the Impressionists, who sought to represent life’s moments exactly as they were.

Seurat’s controlled and precise revisions had both a positive and negative effect on the painting. On the one hand, Seurat was able to rid the backdrop of any nuisances, such as the industrial shipyard that would have clouded the scene. On the other, the couple on the right appear to be giants.

Seurat’s friend, Paul Signac, joked that the reason for this distortion may have been because the canvas was “too large” for Seurat’s small office. Despite this, ‘La Grande Jatte’ will forever remain an iconic work of art.

These days the painting is found in the Art Institute of Chicago.

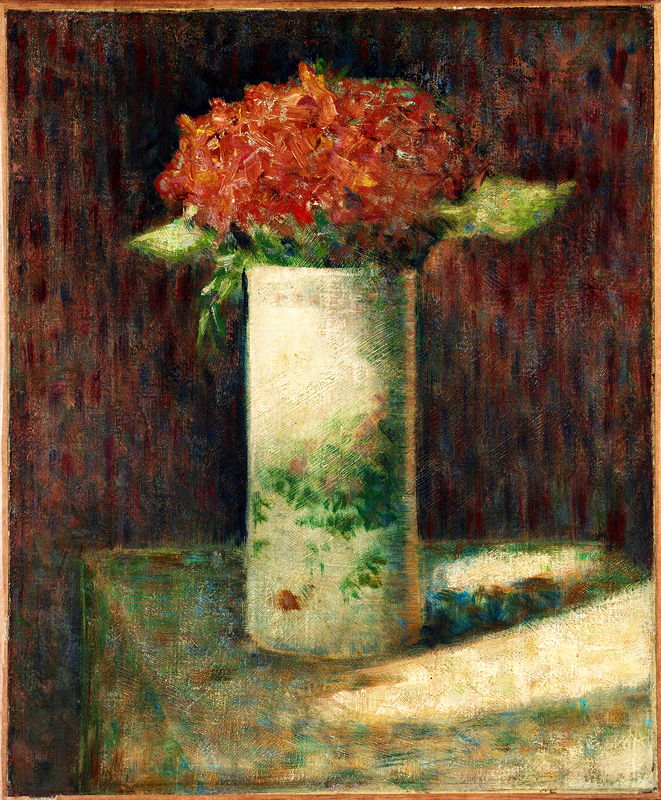

2. Vase of Flowers (1879)

Vase of Flowers is Seurat's only surviving still life.

Though nobody is sure, it is likely that this early effort was created during Seurat's years as a student, something heavily hinted by the elegance of the piece, which draws on the aesthetic of French academic painting.

It is useful to be able to view the work of Seurat as a youth, because it only emphasises the significance of his future achievements.

Seurat once stated that,

“the art of painting is the art of hollowing out a canvas”.

As such, ‘Vase of Flowers’ is interesting from a stylistic standpoint as it shows his investigations before he found his feet with the invention of Pointillism. A thin border of light brown helps contain the motif, which is built up in coats of solid oils. This layering of paint completely contradicts Seurat’s later style, which revolve around a much more refined and delicate application.

The strokes too differ from the characteristic Divisionist procedure that Seurat is famed for. Long, downward, dashed lines depict a moody maroon background. Nearer to the front, the table is moulded through dabs of blue and beige. A shadow is cast to the right, fashioned using crisscrosses of darker blue and brown. For the vase itself, he employs finer brushwork. The paint is pasted so thickly that you can even see physical grooves left by the bristles. By shortening the size of the brushstrokes, Seurat consciously creates perspective.

For the organic segments, there are still smaller strokes. The leaves, outstretched and jagged, are vague. Conversely, the flowers are formed through deliberate, wiggling marks. The strength of the pigments should be acknowledged as well; it is impossible for the eye to ignore the blended reds. Layered on top of the crimson, an occasional streak of pale grey portrays the sheen of the petals. In these stylistic details, it is possible to see Seurat’s initial adoption of Impressionistic techniques, resulting in an accomplished piece for the young artist.

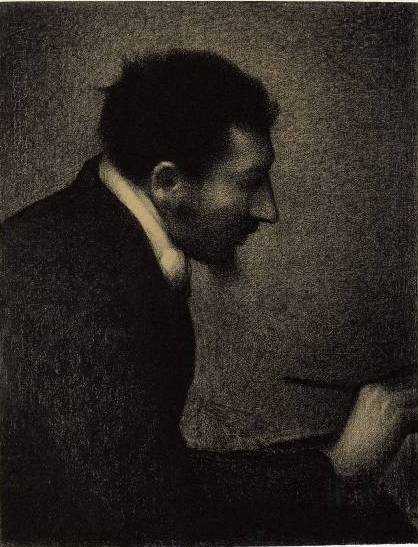

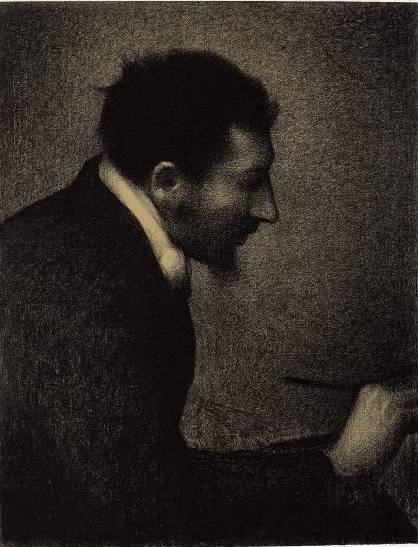

3. Portrait of Edmond-Françoise Aman-Jean (1883)

Aside from producing oil paintings, Seurat was also proficient at sketching.

During his formal education, he studied academic drawing and was schooled by portraitist, Henri Lehmann. This was a very significant move for Seurat as it was Lehmann who tutored the ‘Father of Impressionism’, Camille Pissarro. Encouraged by these early teachings, Seurat lovingly created a collection of pencil portraits of those closest to him.

Some of his first studies centred around his family. A notable picture is ‘The Artist’s Mother’, made in 1882, of Ernestine Faivre. Seurat was incredibly close to his mother as she had raised him and his siblings almost single-handedly after his father, Antoine, moved elsewhere for work. Seurat also turned his attention to his artist friends. Another noteworthy drawing is ‘Portrait of Paul Signac’ (1890) portraying one of Seurat’s closest contemporaries.

The subject in this particular piece is Edmond Aman-Jean, a fellow graduate of the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, with whom Seurat shared a workshop. While at the academy, both young artists were encouraged to copy the drawings of their predecessors to help learn about human anatomy. You can see the traces of these teachings in Seurat’s portrait through the technicality of the linework and the subtlety of the lighting.

The composition depicts Aman-Jean from the side, in deep concentration and holding a paintbrush. The tight framing and atmospheric contrast make the piece feel intimate. Moreover, the dense black juxtaposing the trickles of white are a clear example of Seurat’s signature style when using conté crayons. This was something that won him critical acclaim and in 1883, this portrait was his first piece to be showcased by the Salon. Signac praised Seurat’s illustrations, calling them “the most beautiful painter’s drawings that ever existed”.

4. The Can-Can (1889)

A cherished activity of the Impressionists, along with the Fauves and Cubists to come, was visiting the Moulin Rouge.

Showcasing the can-can, or ‘La Chahut’ in this piece, Seurat represents the high-energy dance craze using linework and tonal contrast. Compacted into a snug frame, dancers and jazz musicians are fabricated through multi-coloured, mottled markings. The dotted brushstrokes echo the rhythm of the performers.

The exuberant colour palette exclusively uses primary and secondary colours. This garish effect shows off Seurat’s interpretation of interior lighting. Seurat was interested in the science behind art and around this time, he studied the works of physicist Ogden Rood, who specialised in colour theory, along with Charles Henry, who investigated form. You can see the influence of both scientists in ‘The Can-Can’ via the calculated colour palette.

Most importantly, this painting provided a template for future abstract artists, including Pablo Picasso. Seurat developed Divisionism to escape the constraints left by Impressionism. Despite this, he did not think of himself as a pioneer, explaining “I apply my method and that is all there is to it”.

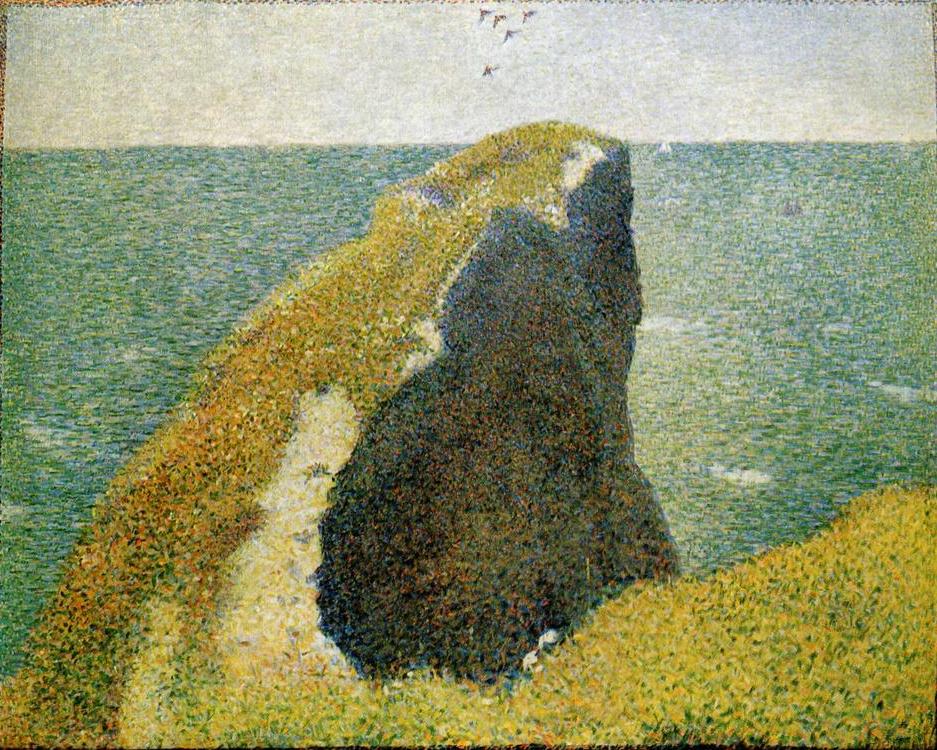

5. Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp (1885)

The Impressionists were notorious for painting outdoor scenes, sitting at their easels in floral fields and verdant forests.

As with several other conventions of the Impressionist movement, the Neo-Impressionists scrapped this method, opting to paint in their studios instead.

‘Le Bec du Hoc’ was first devised by Seurat during a holiday in Normandy. He made a spontaneous study of a rock formation that caught his eye. Bringing the draft back to his home, he created a retrospective painting in his studio.

Aligned centrally, the cliff curves above the horizontal sealine. Birds soar into the sky while boats gently traverse the open waters. Seurat organised the space so that the landscape emanates a sense of width, letting the audience admire the panorama. Using a yellowing base layer, a pathway is depicted. At either side, Pointillist patterns present the textures of the earth and vegetation. Bits of baby blue are added to indicate flowers in bloom. This same shade of blue also appears in the sky, enforcing the repetition. Behind this, the sea is speckled with aquamarine.

As with many of his mature works and in the style of the Impressionists, Seurat rejects black paint. It is the browns, blues and violets that create the shadows. Additionally, Seurat was advised by Camille Pissarro in 1890 to, “abandon earth colours” and“stop using emerald green”. In this picture, Seurat has taken Pissarro’s wisdom onboard, using a variety of greens, yellows and oranges for the grass. In conclusion, ‘Le Bec du Hoc’ illustrates the fusion between time periods, displaying the naturalistic appeal of Impressionism and the transgressive mark-making of Neo-Impressionism.

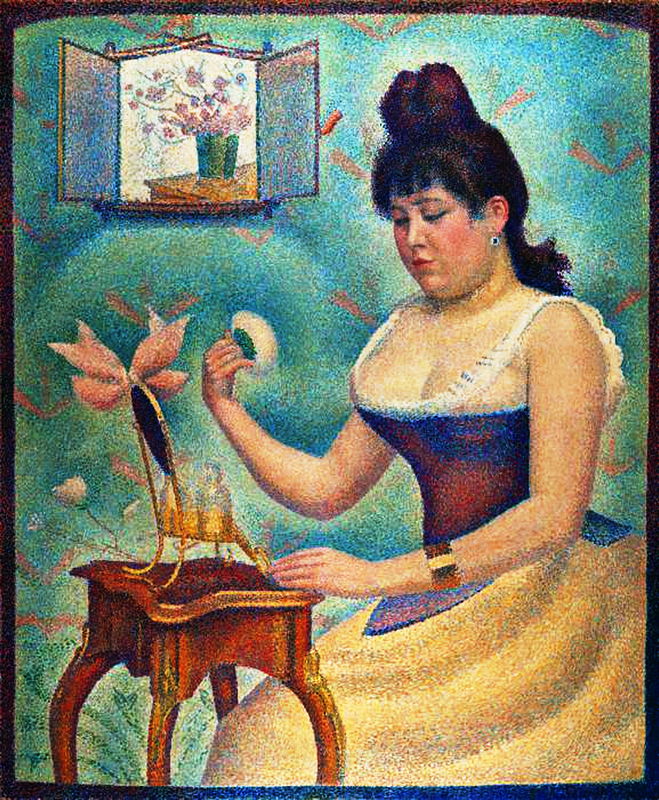

6. Young Woman Powdering Herself (1889)

Due to his academic accolades, Seurat incorporated classicism in his work. This sensitive portrait is reminiscent of Renaissance paintings.

The voluptuous sitter wears a glamorous bodice and a silky skirt. As the garment swoops around her, it accents her extended arm as she gathers makeup. Her face is relaxed and her eyes downcast, giving the impression of privacy.

The model for this piece was Madeleine Knobloch, Seurat’s romantic partner and the mother to his children. However, during the public showing of the painting in 1890, the pair had not announced their relationship, which may explain the secretive finish to the piece. During a digital scan in 2014, it was revealed that the original backdrop for the piece was Seurat at his easel. On reconsideration, he concealed his self-portrait by turning the mirror into a bamboo picture frame.

The soft shades accompanied by the pretty, pink flowers add a touch of femininity to the piece. With the bottles of oil set upon her table, to the painting of the cherry blossoms, the piece gives the illusion of carrying a sweet scent. The lightly swirling pattern of the wallpaper makes the dreamy scene seem like a fairytale illustration. It is a charming tribute to Seurat’s companion.

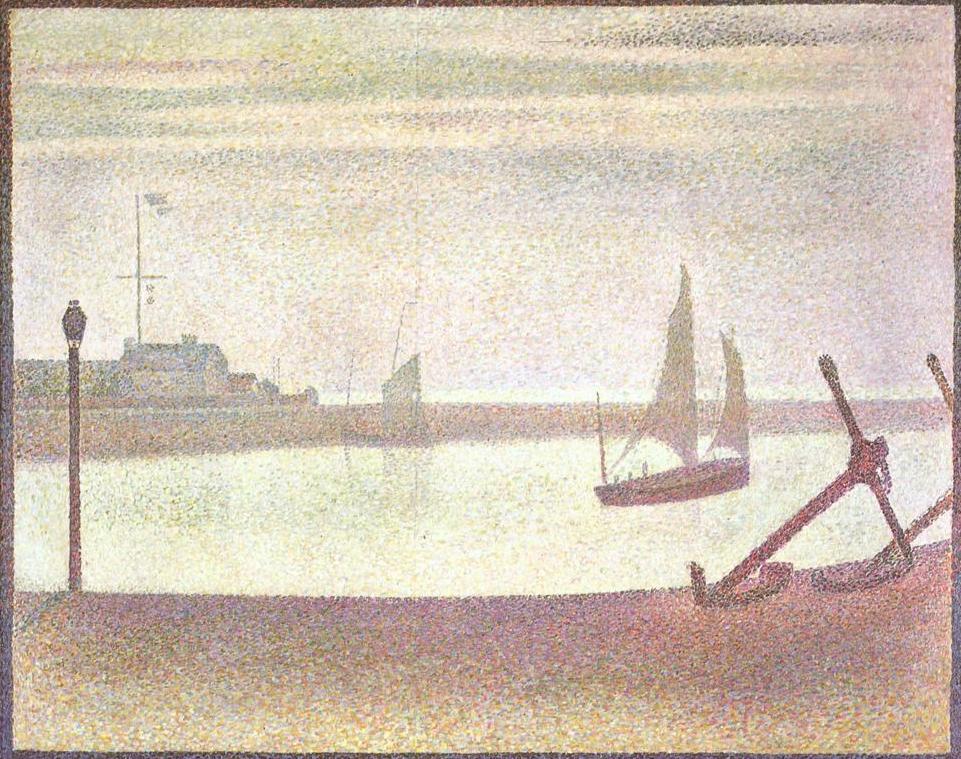

7. The Channel at Gravelines, Evening (1890)

Mild in colour, this Pointillist picture captures a harbour at night. Following the Impressionist tradition, this piece was part of a series depicting the same location at different times of day.

This work can be directly compared to Seurat’s ‘Petit Fort-Philippe’, which shows the dock draped in the white light of noon. For ‘The Channel at Gravelines’, Seurat made a study on a panel before transferring it to a finalised canvas.

He nicknamed these introductory sketches his “croûtons”. Often, they would involve painting in splotches to formulate the basic premise. After tailoring the image further in the comfort of his studio, Seurat would then labour over the final piece.

The close-knit brushwork in ‘The Channel at Gravelines’ contradicts the widely spaced layout. To the left is a lamppost and to the right are tilted anchors. Using a lighter tone, Seurat depicts ships with scythe-shaped sails moored, adding a ghostly essence. The flat horizon line gives the impression that the sea is unmoving yet the spotted paint shows that water is alive, sparkling beneath the slowly descending sun. Seurat makes his frenetic brushstrokes seem motionless.

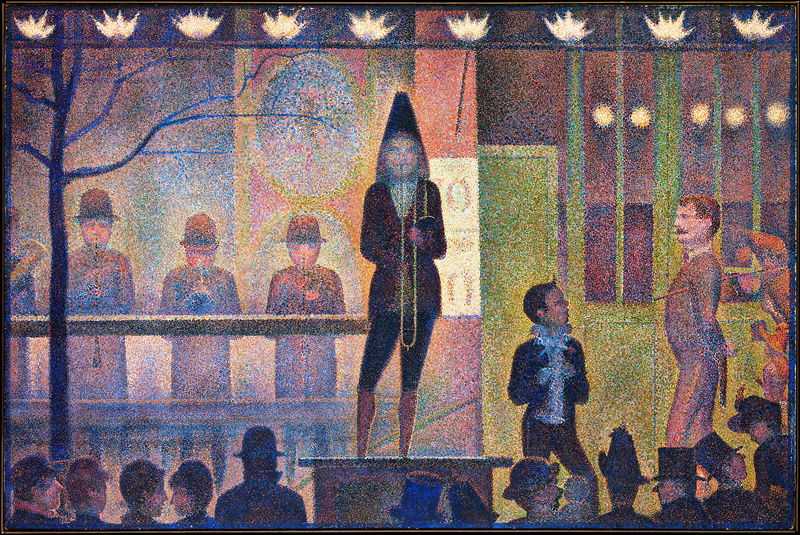

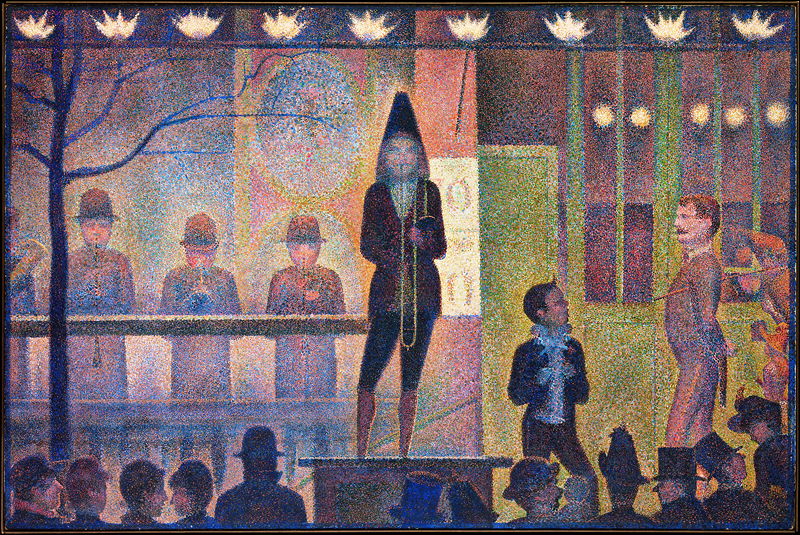

8. Circus Sideshow (1887)

An ambitious artwork by Seurat, ‘Circus Sideshow’ was a technical feat. A larger canvas, this piece tested how well he could paint a nocturnal event.

When displayed at the ‘Salon de Indépendants’ in 1888, critics observed how Seurat had interpreted artificial light, a technique that was uncommon for Post-Impressionists.

Set in a darkened space, the miniscule dots of paint make the scene flicker as if lit by candlelight. The brushwork in this piece has led some to believe that it may have been raining, with the muted colours causing a grainy effect. In a message to the art dealer, Félix Fénéon, Seurat described “the purity of the spectral element”. It makes sense therefore that the pedestrians in this piece are phantom-like. In response, Fénéon labelled Seurat’s painting system “a polychrome mass”.

Divided into vertical panels, the background separates the scene into its various happenings. The left-hand section displays cornet players in bowler hats. The middle section concentrates on a tall trombone player. The right-hand section depicts suited ushers. Split into portions, this composition is called the ‘Rule of Thirds’. This choice by Seurat guarantees that he regarded every part of the demanding painting equally. It is also a nod to his love of geometry. Although the colour scheme is limited, Seurat establishes a lively scene wherein you can almost hear the hum of the misty musicians and the flocking crowd.

9. Fishermen (1883)

Alongside his grander works, Seurat also completed several smaller landscapes.

Although known for pushing the boundaries in terms of his approach to painting, Seurat was somewhat conventional when it came to subject matter. The Impressionists delighted in their immediate surroundings, often staying within their local area to paint. Similarly, Seurat did not stray far. For him, the rivers of Paris provided the perfect vision of 1800s France.

It is estimated from the rougher style of this Genre piece that it was one of the rare instances where Seurat painted on the spot. The crosshatching suggests that he worked quickly, especially as the light’s brightness seemed to be fading. The water and plants are formed using coarse daubs. Over the silvery river, fishing rods are depicted via hazy lines. Bent at diagonal angles they create cross-sections within the composition. On these features, Seurat explained to the journalist Maurice Beaubourg, “harmony is the analogy of opposites, the analogy of similarities of tone, of tint, of line”.

As always, Seurat put thought into how he placed people within his canvas. Fishermen, both on the bank and in rowing boats, cast their lines into the water, waiting for a catch. The seeping scarlet on the shoreside implies an impending sunset. This is accentuated by the faceless silhouettes, who, with their backs to the onlooker, create intrigue by partially obscuring some of the goings-on. This scene encapsulates the simplicity of leisure, letting the spectator feel as if they were a visitor walking past.

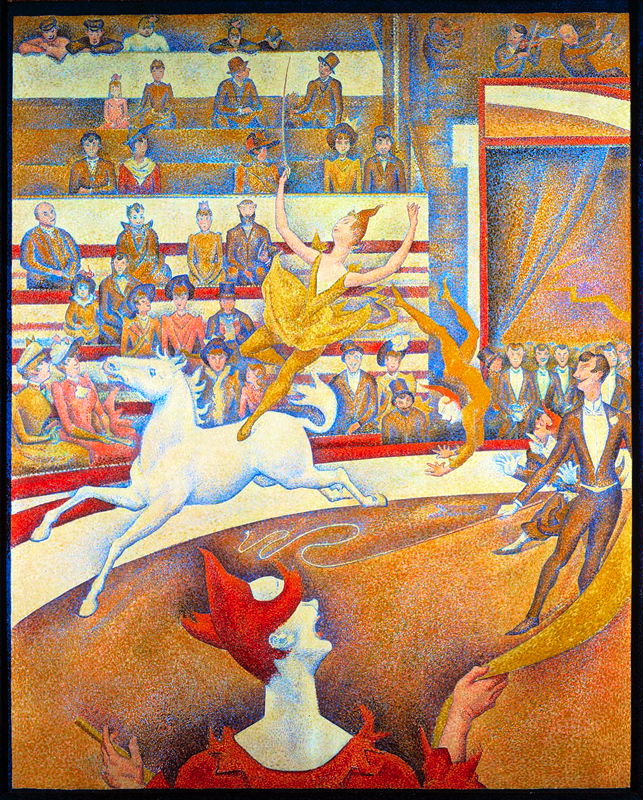

10. The Circus (1891)

Unfinished thanks to his untimely death, ‘The Circus’ is a testament to Seurat’s life, works and skills.

Though his final adventure, it was his third painting centred on the theme of the circus. Adorned with a deep blue frame, the flamboyancy of the piece bursts forward. An adoring homage to the Circus Fernando, this painting displays a slice of French history.

The main notion theme is that of motion. The movement in the scene is non-stop. A gallant horse gallops with a balletic dancer on its back, her hair held gloriously in the air. An acrobat is frozen mid-flip. All the while, from the right hands of the ringmaster and Médrano the clown, a twisting cloth and a curled whip zigzag like lightning.

The rippling fabric of the performers’ clothes become even more dramatic when positioned in front of the quiet crowd, politely watching the antics take place. Situated in rows of tiered seats, Seurat touches on a social commentary about classism. Nearer to the act, ladies and gentlemen sit upright in formal attire. At the back, bystanders lean over the stalls. Regardless of status, Seurat has painted watchful eyes and pleasant smiles onto some of their faces.

Seurat’s use of line and colour create the electricity of the piece. In a text dating from 1890, he describes vibrant tones and ascending actions as evoking excitement, “gaiety… is the luminous dominant, of tint, the warm dominant, of line, lines above the horizontal.” Vitality is crafted through the stark combination of bright yellow and blue. The ecstatic feel is continued via the thousands of dots he carefully applied to the canvas.

A report in 1891 applauded Seurat for the “undulating music of lines” conveyed in ‘The Circus’. It is almost ironic that Seurat’s conclusive masterwork was such a fun image given the tragic circumstances of his death. Nevertheless, the painting stands as a landmark, confirming every creative milestone that Seurat made throughout his career. Although ‘The Circus’ remains unfinished, it is a remarkable piece in its own right.